- Polytrauma and Haemorrhagic Shock

- Blood Tests Predicting Haemorrhagic Shock

{}

Polytrauma and Haemorrhagic Shock

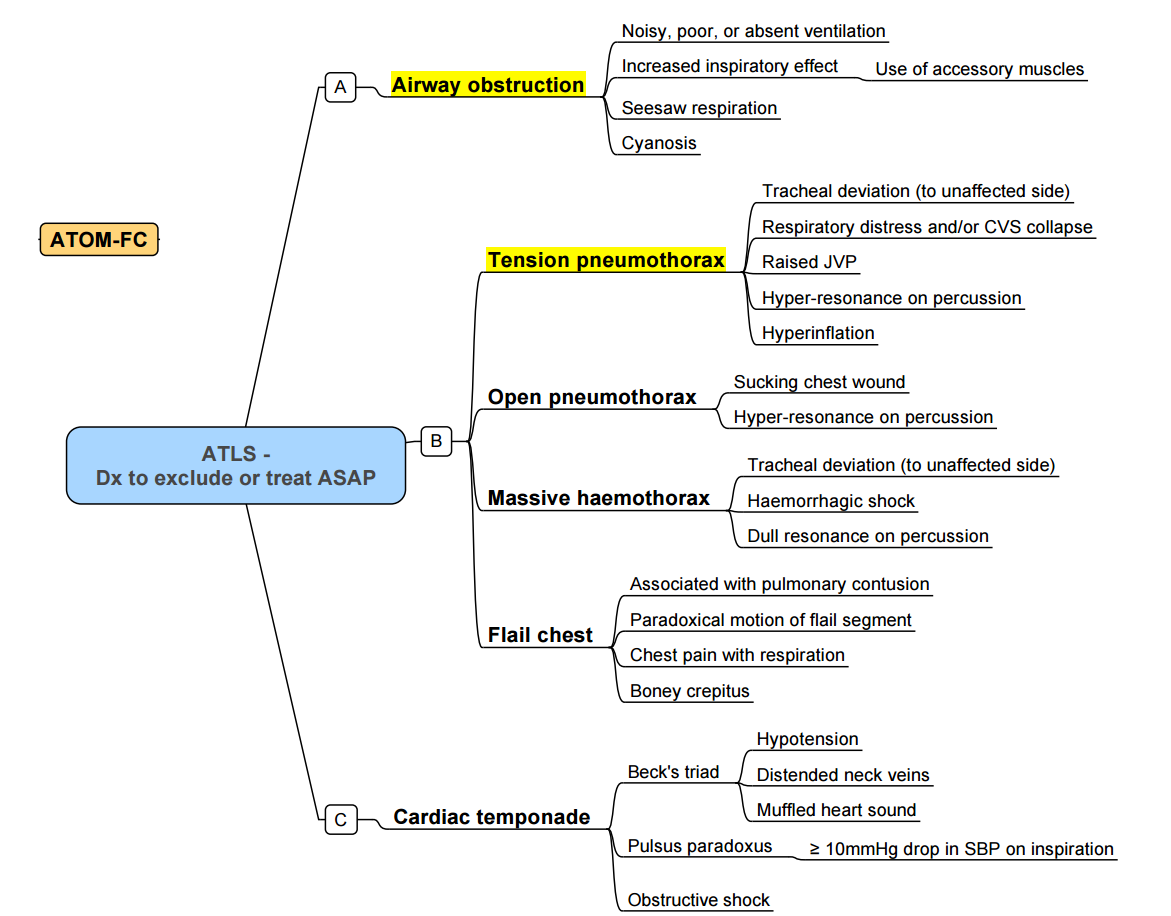

ATLS Summary

- Half of trauma deaths occur immediately, another 30% within a few hours of injury and up to a third of all trauma deaths are due to exsanguination

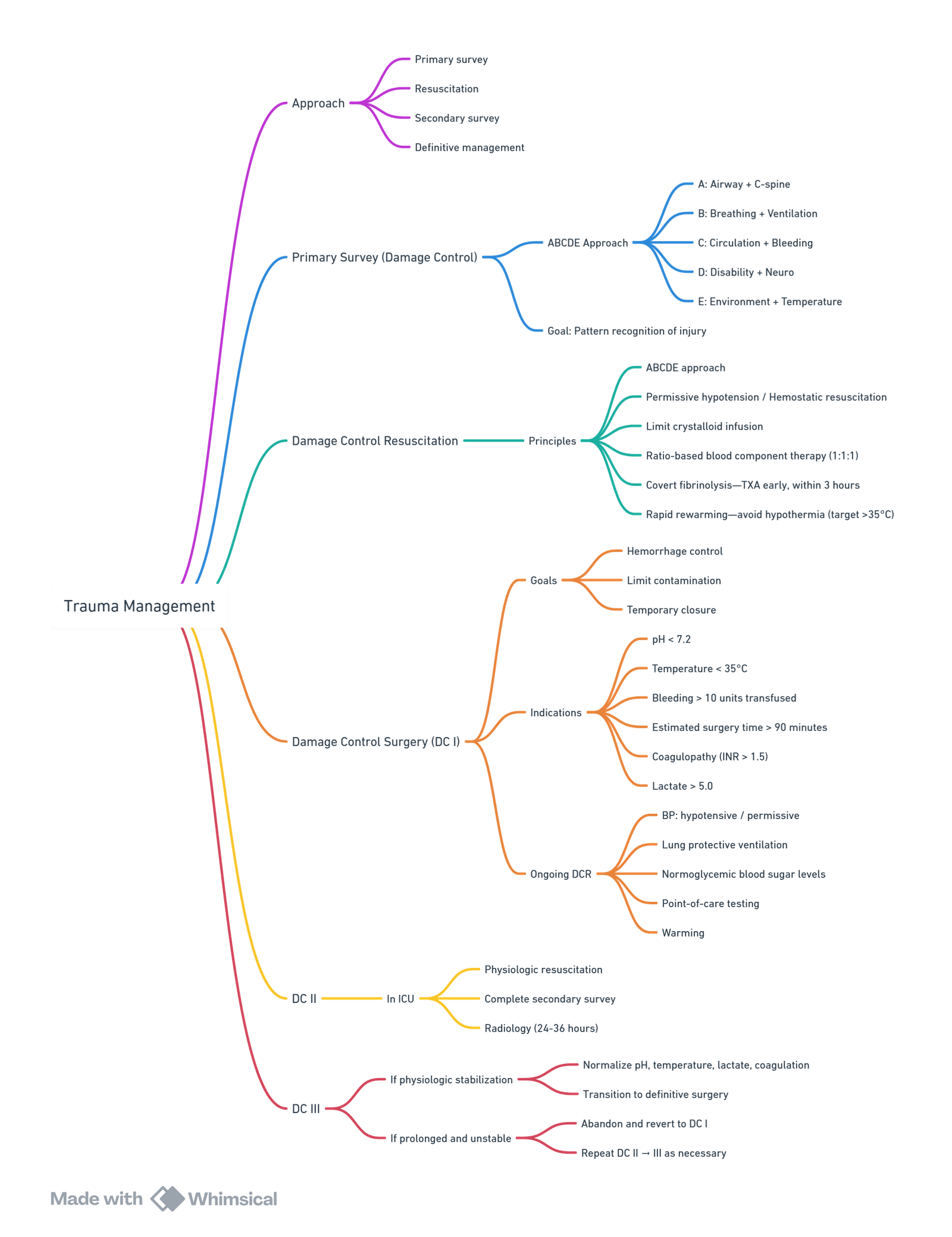

Basic Approach to Trauma Management

ATLS, DCR, DCS

The management of trauma patients follows the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) guidelines, Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR), and Damage Control Surgery (DCS) principles. There are four phases of trauma care:

- Primary Survey

- Resuscitation

- Secondary Survey

- Definitive Care

The primary survey and resuscitation phases are conducted simultaneously.

Acute Management

A – Airway and Cervical Spine Control

- Priority is given to airway management and cervical spine control, but with simultaneous management of the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, Circulation).

- Identify and mark the cricothyroid membrane before initiating Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI).

- Ensure availability of appropriate staff and equipment for airway rescue, including video laryngoscopy, second-generation laryngeal mask airways (LMAs), bougie, and fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB).

- Evaluate the risk-benefit ratio of RSI, considering the intubator’s experience and the difficulty of the procedure.

B – Breathing

- Utilize lung-protective ventilation strategies, except in the following cases:

- Impending brain herniation, where temporary hyperventilation is indicated.

- Lung injury, where permissive hypercapnia is acceptable.

C – Circulation

- Follow Damage Control Resuscitation (DCR) principles.

- A deteriorating level of consciousness due to hypovolemia indicates a loss of at least 40-50% of blood volume.

D – Disability (Neurological Assessment)

- Avoid systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 110 mmHg in traumatic brain injury (TBI).

- Use the AVPU scale for neurological assessment.

- A single episode of hypotension significantly increases morbidity and mortality in TBI. Hypoxia should be prevented to avoid secondary brain injury.

E – Exposure and Environmental Control

- Prevent hypothermia and maintain body temperature > 35°C.

- For penetrating exsanguinating wounds, control bleeding immediately, even before completing the ABCDE assessment.

Other Anaesthetic Considerations

- Prolonged surgery

- Involvement of multiple surgical teams

- Large fluid loss

- Acute lung injury

- Hypotension

- Hypoxia

- Hypertension

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Note: Early Total Care (ETC) is the fixation of long bone fractures within the first 24 hours post-injury, but only in a stable patient after resuscitation.

Coagulation Targets

| Factor | Target | Response |

|---|---|---|

| INR and aPTT | < 1.5 of normal | If high, give FFP 30 mL/kg |

| Fibrinogen | 1.5–2 g/L | Replace with cryoprecipitate |

| Platelet count | 75 × 10^9/L | Replace with 1 adult therapeutic dose (ATD) |

| (100 if ongoing bleeding or head injury) |

- No single parameter provides adequate indication to end points of resuscitation. Currently lactate is used as a surrogate marker of adequacy of resuscitation. Lactate coupled with acid base status may also be a useful marker of resuscitation with improving lactate and resolution of acidosis. Serial measurement of lactate levels have also been described to aid decision to DCS in the first 12-24 hours

ABC Score for Massive Transfusion

- Score < 2: Unlikely need for massive transfusion

- Criteria:

- SBP ≤ 90

- HR ≥ 120

- Positive FAST (Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma)

- Penetrating torso injury

Damage Control Surgery

Definition

- Initial surgery on a haemodynamically unstable, actively bleeding trauma patient should be focused on anatomic control of bleeding, with repair of less significant or time-critical procedures deferred until resuscitation is completed.

- Damage control is intended to minimize operating theatre time, minimize ongoing fluid administration, and preserve normothermia, thus reducing the secondary surgical and inflammatory insult that would arise from extensive bowel or soft-tissue reconstruction, orthopaedic manipulation, or other less essential procedures.

Essentials of Damage Control Anaesthesia

- Airway and ventilator management:

- Rapid sequence intubation

- Titration of ventilation

- Control of bleeding:

- Deliberate hypotensive resuscitation

- Maintenance of blood composition

- Preservation of homeostasis:

- Normothermia

- Restored and sustained end-organ perfusion

- Analgesia and sedation

Goals

- Arresting haemorrhage

- Limiting contamination

- Maintaining optimal flow to vital organs and extremities (decompression of compartments, splint fractures)

- Minimise operative time to avoid further hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy (<90mins)

Indications for DCS

- Significant bleeding (massive TF)

- Severe metabolic acidosis (pH <7.30)

- Hypothermia (T<35)

- Operative time >90min

- Coagulopathy

- Lactate >5

Stage of DCS

- Part zero (DC 0)

- emphasizes injury pattern recognition for potential damage control beneficiaries and manifests in truncated scene times for the emergency services and abbreviated emergency department DCR by the trauma team. Rapid-sequence induction (RSI) of anaesthesia and intubation, early rewarming, and expedient transport to the operating theatre are the key elements.

- Part one (DC I)

- occurs once the patient has arrived in theatre and consists of immediate exploratory laparotomy with rapid control of bleeding and contamination, abdominal packing, and temporary wound closure.

- Part two (DC II)

- is the intensive care unit (ICU) resuscitative phase where physiological and biochemical stabilization is achieved and a thorough tertiary examination is performed to identify all injuries.

- Part three (DC III)

- occurs once physiology has normalized and consists of re-exploration in theatre to perform definitive repair of all injuries. This may require several separate visits to theatre if multiple systems are injured and require operative treatment.

DCS vs. Early Total Care (ETC)

- DCS has been described above and consists of 4 components i) haemorrhage control ii) decompression of compartments (thorax, abdomen, limbs, cranium) iii) decompression of wounds and ruptured viscera iv) fracture splints

- ETC is defined as definitive surgery with fixation of all long bone fractures within 24 hours of injury, but only once the patient has been stabilized. The decision between DCS and ETC (definitive surgery) may be difficult. The decision to continue with ETC instead of DCS should be made with close communication and co-operation between surgical teams, ICU and Anaesthesia.

Damage Control Resuscitation

- The lethal triad of coagulopathy, hypothermia and acidosis compounds morbidity and mortality associated with traumatic haemorrhage

- DCR describes the rapid correction of hypothermia and acidosis, as well as the direct treatment of coagulopathy. It involves early transfusion of trauma patients, the use of permissive hypotension and minimization of crystalloid use, massive transfusion protocols, tranexamic acid and damage control surgery

Summary

- Damage control resuscitation:

- aim SBP 80-90mmHg unless TBI, then >90mmHg

- target Hb 7-9g/dl

- normothermia (avoid passive cooling, and active warming)

- Activate MTP

- high plasma:rbc 1:1

- target fibrinogen 1.5-2g/l

- avoid crystalloids

- Haemostatic resuscitation

- TXA within 3 hours of injury

- point of care viscoelastic guidance of products

- avoid hypothermia, haemodilution and acidosis

- Damage control surgery

- stop bleeding, limit contamination, decompress compartments, splint fractures

- consider when pH <7.3, RBC transfused >10, temp <35°C, surgery time >90min, clinically coagulopathic (oozy), lactate >5mmol/l

Components

- CABC resus

- Time limited permissive hypotension (controlled fluid resuscitation): The aim is to limit fluid resuscitation until haemorrhage control has been achieved, thereby reducing clot disruption and the dilutional coagulopathy. The key is promptly recognizing the bleeding source with earliest possible control (surgery or interventional radiology) and limiting the time of permissive hypotension, after which definitive resuscitation becomes the goal

- Fluid: Colloids rapidly restores circulatory goals although no survival benefit have been shown for colloids. Crystalloids, on the other hand are cheaper but large volumes are associated with complications of tissue oedema and increased abdominal compartment syndrome. Current evidence supports the use of colloids solutions in the context of perioperative and trauma medicine, when acute plasma volume expansion is appropriate and when haemodynamic stabilisation is under taken in the acute phase

- MTP, TEG driven transfusion: Early aggressive transfusion improves outcome and using higher plasma to RBC transfusion ratios have been associated with lower overall blood product usage. 1:1:1 is not universally advocated. There is a U-shaped curve with respect to optimal ratio of plasma to RBC, with a ratio of 1:2 associated with the lowest mortality rates, ratios both higher and lower demonstrate increased mortality

- Recombinant factor 7: It is usefulness as adjunct to treatment of surgical bleeding and binds exposed tissue factor, amplifying factor X conversion promoting thrombin generation, platelet activation and fibrin clot formation

- Cyclokapron: CRASH-2 demonstrated early treatment with TXA, within 1-hour of surgery, significantly reduced the risk of death from bleeding. It is more effective in penetrating than blunt trauma. Current recommendations are in all trauma patients with evidence of haemorrhage and a) early presentation (within 3 hours of injury) b) systolic blood pressure <110 mm Hg or c) heart rate > 110 bpm d) or both

- Arterial blood gas: Hypocalcaemia is real danger with MTP and calcium levels should be monitored. Lactate monitoring

- DCS

- Damage control radiology

- Correct electrolytes

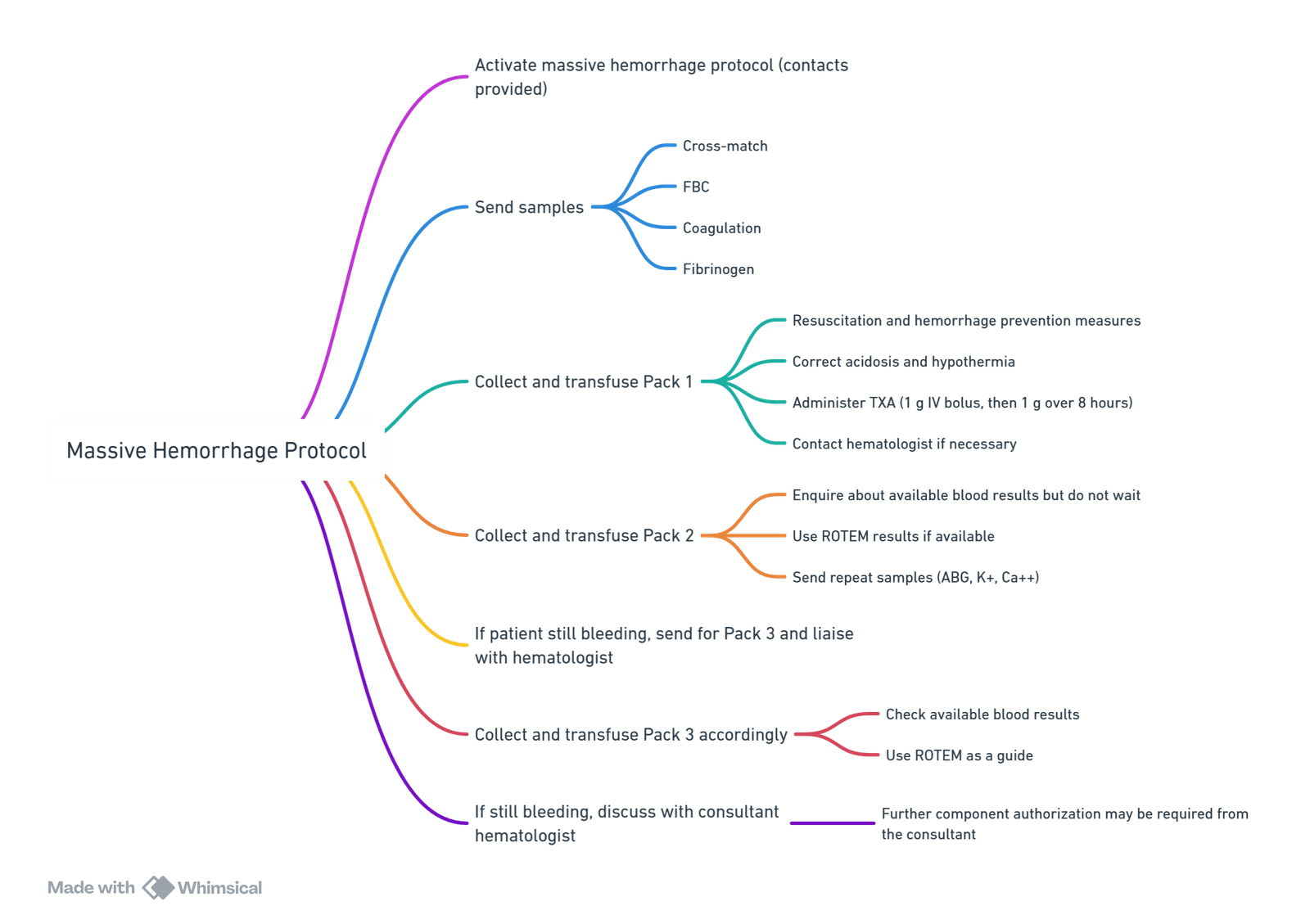

Massive Hemorrhage Protocol

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Transfusion targets:

- Hb: 70–90 g/L

- Platelets: >75 × 10^9/L (100 if ongoing bleeding or TBI)

- PT/aPTT: < 1.5 × normal

- Fibrinogen: >1.5–2.0 g/L

Hypotensive Resus

- Controversial

Considered part of damage control resuscitation

Allow SBP to fall low enough to avoid exsanguination but high enough to maintain perfusion. Short term. Until definitive management in theatre.

Problems: - Largely bases on evidence from animal studies

- Varying interpretations on approach

- Non haemorrhagic causes of hypotension must not be missed

- Potentially dangerous if long retrieval times occur

- Concerns in the setting of traumatic brain injury

- Appropriate BP is relative to patient (HPT may need higher BP)

Damage Control Radiology

- The term is used parallel to DCS and DCR from patient retrieval, transfer and appropriate primary treatment.

- The aims are:

- Rapid identification of life-threatening injuries,

- Identification/exclusion of head or spinal injury

- Accurate triage of patients to theatre for thoracic and/or abdominal surgery or angiography suite for endovascular control of haemorrhage.

- Early CT (within 30 minutes of arrival) has become the investigation of choice for the severely injured adult patient and indicator of quality and efficiency of the trauma team

- REBOA (Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta):

- Increasingly used for non-compressible torso haemorrhage in the ‘golden hour’ or prehospital ‘platinum 5 minutes’.

- May be lifesaving when applied early with proper patient selection, although ischaemic complications require careful management

Trauma Induced Coagulopathy

- Coagulopathy is one of the most preventable causes of death in trauma and has been implicated as the cause of almost half of haemorrhagic deaths in trauma patients

- 6 key interacting mechanisms that lead to this coagulopathy: tissue trauma, shock, haemodilution, hypothermia, acidaemia and inflammation

- Acute coagulopathy has recently been identified at admission before trauma resuscitation in one in four trauma patients and is associated with a fourfold increase in mortality

- Coagulopathy in the acute phase of trauma patients consists of two core components:

- (1) trauma itself and/ or traumatic shock-induced endogenous ATC

- (2) resuscitation-associated coagulopathy

- 3 phases:

- The first phase is immediate activation of multiple haemostatic pathways, with increased fibrinolysis, in association with tissue injury and/or tissue hypoperfusion.

- The second phase involves therapy-related factors during resuscitation.

- The third, post-resuscitation, phase is an acute-phase response leading to a prothrombotic state predisposing to venous thromboembolism.

Two Components

- Acute Traumatic Coagulopathy (ATC):

- Caused by trauma itself and traumatic shock.

- Hyperfibrinolysis and hypocoagulable state.

- Presents immediately after injury and continues during resuscitation.

- Resuscitation-Associated Coagulopathy (RAC):

- Involves hypothermia, metabolic acidosis, and dilutional coagulopathy.

- Aggravates TIC during and post-resuscitation.

Trauma-Induced Coagulopathy Phases

- Pre-Hospital Resuscitation:

- Trauma tissue injury and traumatic shock

- Acute traumatic coagulopathy (ATC)

- In-Hospital Resuscitation:

- Consumption of coagulation factors

- Dilutional coagulopathy

- Acidosis and hypothermia

- Post-Resuscitation Phase:

- Trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC)

- Hemorrhage

Pathophysiology

- Primary Pathologies:

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC):

- Activation of coagulation

- Insufficient anticoagulation mechanisms

- Increased fibrinolysis (early phase)

- Suppression of fibrinolysis (late phase)

- Consumption coagulopathy

- Acute Coagulopathy of Trauma-Shock (ACOTS):

- Activated protein C-mediated suppression of coagulation

- Increased fibrinolysis

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC):

- Secondary Pathologies:

- Anemia-induced coagulopathy

- Hypothermia-induced coagulopathy

- Acidosis-induced coagulopathy

- Dilutional coagulopathy

Trauma Response Mechanisms

- Trauma and Trauma Shock:

- Hypotension/hypoperfusion

- Inflammatory response → cytokines

- Thrombomodulin Activation:

- Binds thrombin and activates protein C

- Endothelial Glycocalyx Disruption:

- Damage from hypoperfusion

- Release of heparan sulfate, promoting anticoagulation

- Platelet Dysfunction:

- Due to activated protein C and inflammatory mediators

Acute Traumatic Coagulopathy

- Causes:

- Hyperfibrinolysis

- Depletion of coagulation factors

Resuscitation-Associated Coagulopathy

- Main Points:

- Hypothermia

- Acidosis

- Dilution of clotting factors

Physiological Changes:

- Hemostasis and wound healing

Pathological Changes:

- Endogenously induced primary pathologies

- Exogenously induced secondary pathologies

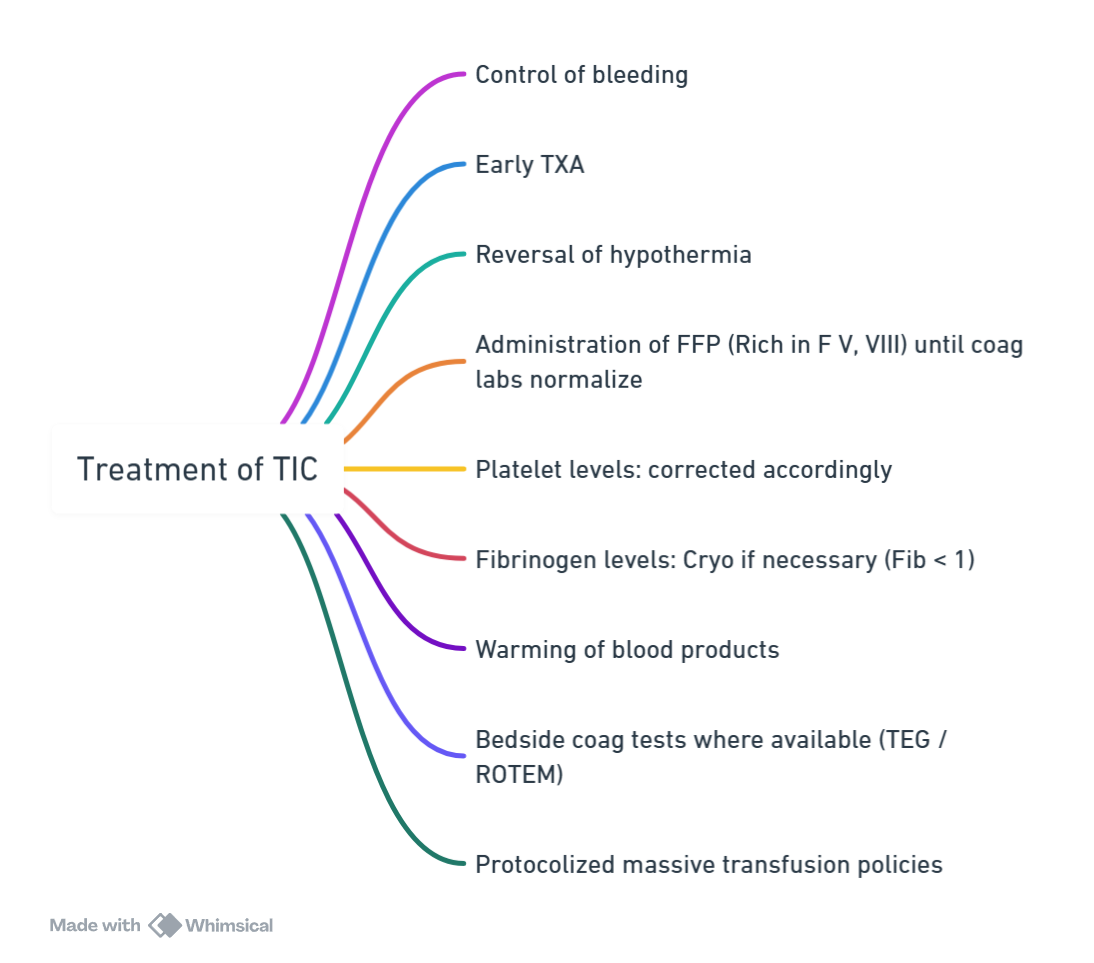

Treatment

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Currently Recommended Management for TIC

Initial Assessment and Management:

- Assess extent of traumatic hemorrhage.

- Immediate treatment of identified sources of bleeding in patients in shock.

- Further investigation for unidentified sources of bleeding in patients in shock.

- Assess coagulation, hematocrit, serum lactate, base deficit.

- Initiate antifibrinolytic therapy (tranexamic acid within 3 hours post-injury).

- Assess patient history of anticoagulant therapy.

Resuscitation:

- Achieve systolic blood pressure of 80-90 mmHg (without traumatic brain injury).

- Implement measures to achieve normothermia.

- Maintain hemoglobin level between 7-9 g/dL.

- Administer 1:1:1 transfusion ratio

- Early PCC testing + goal-directed therapy

Surgical Intervention:

- Perform damage control surgery in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Coagulation Management:

- Employ massive transfusion protocol with a high plasma to red blood cell ratio.

- Achieve target fibrinogen level of 1.5-2 g/L.

- Achieve target platelet level.

- Administer prothrombin complex concentrate if indicated (e.g., vitamin K antagonist, oral anticoagulant, or evidence from viscoelastic monitoring).

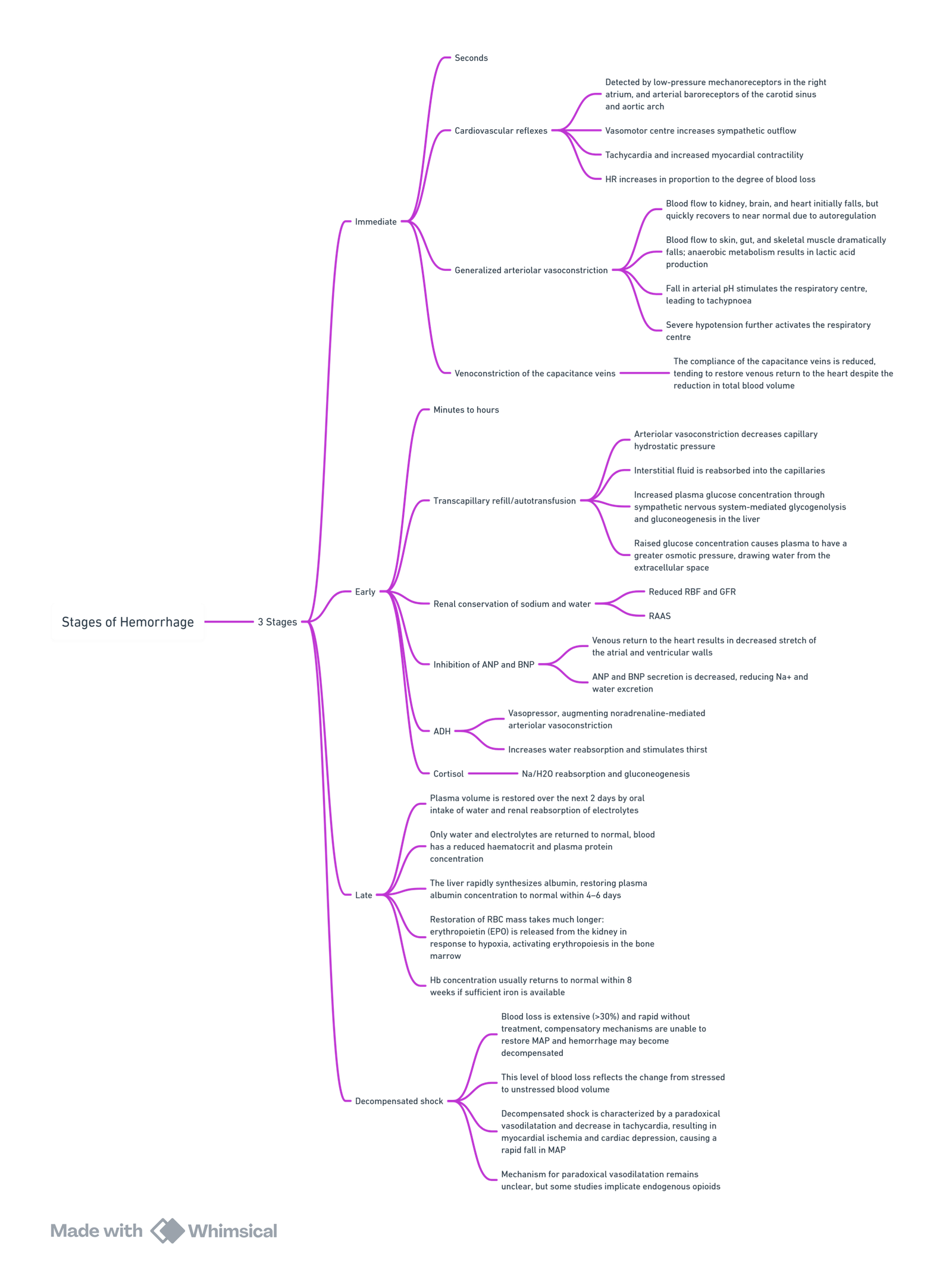

Physiological Changes in Haemorrhage

- Fall in circulating volume and reduced preload. Fall in CO results in decreased MAP.

- Organ perfusion pressure falls, leading to organ dysfunction. The cardiovascular, nervous and endocrine systems act to redistribute blood flow to the vital organs, namely the brain, the heart and, to a lesser extent, the kidneys

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Categories of Haemorrhagic Shock

| Class | Blood Loss (%) | Blood Loss (mL, 70 kg adult) | HR (bpm) | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | RR (breaths/min) | Urine Output (mL/h) | Mental Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | <15 | <750 | <100 | Normal | Normal | <20 | >30 | Normal |

| Class 2 | 15-30 | 750-1500 | >100 | Normal | Raised | 20-30 | 20-30 | Anxious |

| Class 3 | 30-40 | 1500-2000 | >120 | Reduced | Reduced | 30-40 | 5-15 | Confused |

| Class 4 | >40 | >2000 | >140 | Very Low | Very Low | >35 | Negligible | Drowsy or Unconscious |

Notes:

- Class 1 and 2 hemorrhagic shock are compensated shock, maintaining blood pressure.

- Class 3 and 4 hemorrhagic shock are decompensated, with hypotension.

- Decompensated shock is associated with >50% mortality.

- Pure hemorrhagic shock is rare; it often occurs in conjunction with trauma and triggers a cascade of inflammatory mediators leading to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and organ dysfunction, increasing mortality.

Pathophysiology of Haemorrhagic Shock

Trauma and Coagulopathy Pathway

- Trauma leads to:

- Blood loss

- Ischemia

- Coagulopathy

- Release of inflammatory mediators

- Blood Loss and Ischemia result in

- Fibrinolytics activation

- Cellular distress

- Coagulopathy causes:

- Cellular distress

- Inflammatory Mediators and Toxins (e.g., lactate) contribute to:

- Cellular distress

- Cellular Distress leads to:

- Apoptosis

- Necrosis

- Organ failure

- Organ Failure can be:

- Acute (brain, heart)

- Sub-acute (lungs, kidneys, gut, immune)

- Ultimately, these processes can result in Death.

- Trauma is both a local and a systemic disease.

- Pathophysiology begins with direct damage to tissue by external energy (the definition of trauma).

- This creates both tissue injury and pain. Disruption of blood vessels and solid organ parenchyma causes haemorrhage and a decrease in cardiac output.

- Systemic compensation occurs through increased sympathetic outflow, leading to increased heart rate and vasoconstriction of non-essential tissues. When bleeding is severe enough to overwhelm systemic compensation, the result is tissue hypoperfusion, or shock.

- Damaged and under-perfused cells become distressed, and react through release of toxins and mediators.

- Anaerobic metabolism generates metabolic by-products (lactate and other acids) that create further damage both locally and systemically.

- Hundreds of other compounds are released by the ischaemic cell, including interleukins, tumour necrosis factor, and complement proteins.3 These bioactive molecules in turn create an amplified reaction throughout the body, transforming a local event into a systemic disease.

- Thrombin triggers liberation of protein C from thrombomodulin; protein C binds to plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, thus producing a fibrinolytic state.

- Coagulopathy leads to increased haemorrhage and thus progression of ischaemia, causing further cellular injury in a downward spiral that will lead to death from exsanguination if not interrupted.

- Consumption of available clotting factor and platelet reserves, serum acidosis, and systemic hypothermia will contribute to the ‘bloody vicious cycle’ of bleeding, coagulopathy, and further bleeding.

- Fluids can result in increased bleeding: mechanical –> increased pressure –> forces fluid out of damaged circulation and washes away early blood clots.

- Asanguineous resuscitation fluids—isotonic crystalloids and non-blood colloids—dilute the concentration of red cells, clotting factors, and platelets.12 Exogenous fluids are likely to be cooler than body temperature, contributing to hypothermia. Rapid administration of crystalloids damages the endothelial glycocalyx, leading to increased extravasation.13 Research also suggests that crystalloids may have pro-inflammatory side-effects.

Blood Tests Predicting Haemorrhagic Shock

Fibrinogen

Normal Levels

- At term: 4-6 g/L.

Diagnostic Value

- Predictive Value: A fibrinogen level <2 g/L has a 100% positive predictive value for progression from moderate to severe postpartum haemorrhage (PPH).

Bedside Testing

- ROTEM (Rotational Thromboelastometry): Utilizes cytochalasin D to remove platelet contribution.

- FibTEM A5: Measures the amplitude 5 minutes after clot formation starts.

- Treatment Thresholds:

- FibTEM A5 <7 mm

- FibTEM A5 <12 mm with ongoing bleeding

- Treatment Thresholds:

Replacement Therapy

To increase fibrinogen by 1 g/L:

- Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP): 30 ml/kg

- Cryoprecipitate: 3 ml/kg

- Fibrinogen Concentrate: 60 mg/kg (1 g/50 ml)

Summary of Evidence

Key Recent Evidence (2017 – 2025)

| Study (first author / acronym) | Year | Design | n | Intervention vs. Control | Main outcome(s) | Key results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRASH-3 (Shakur-Still) | 2019 | Multicentre RCT | 12 737 | 2 g tranexamic acid (TXA) ≤3 h after injury vs. placebo in TBI | Head-injury death by 28 d | Early TXA reduced mortality in mild–moderate TBI (RR 0.78) with no increase in vascular events | nejm.org |

| PATCH-Trauma | 2023 | Pre-hospital RCT | 1 310 | 1 g TXA bolus + 1 g infusion vs. placebo in major trauma | Favourable 6-month GOS-E; 28-d mortality | No difference in function; 28-d death lower with TXA (17.3 % vs. 21.8 %) | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| PAMPer (Sperry) | 2018 | Cluster RCT | 501 | 2 units thawed plasma in air transport vs. standard crystalloid | 30-d mortality | Plasma reduced 30-d death (23 % vs. 33 %) and improved coagulation indices | nejm.org |

| ITACTIC (Baksaas-Aasen) | 2020 | Multicentre RCT | 396 | VHA-guided massive haemorrhage protocol vs. conventional labs | Alive & free of massive transfusion at 24 h | No overall benefit (67 % vs. 64 %); possible signal in TBI subgroup | link.springer.com |

| AVERT-Shock (Sims) | 2019 | Double-blind RCT | 100 | Low-dose arginine-vasopressin vs. placebo in haemorrhagic shock | Blood product volume at 48 h | Vasopressin halved transfusion volume; no mortality difference; fewer DVTs | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| UK-REBOA trial | 2024 | Pragmatic RCT | 90 | REBOA + standard care vs. standard care | 90-d all-cause mortality | Higher death with REBOA (54 % vs. 42 %; OR 1.58); posterior probability of harm 87 % | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| Whole-blood resuscitation (EAST guideline meta-analysis) | 2024 | Systematic review & meta-analysis (18 studies) | 7 687 | Low-titre group O whole blood vs. component therapy | Early mortality ≤24 h | Whole blood associated with improved early survival; certainty low-moderate | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| Pre-hospital TXA (updated meta-analysis) | 2024 | Systematic review & meta-analysis (33 studies) | 25 943 | Pre-hospital TXA vs. no TXA | 24 h & 28–38 d mortality; safety |

Links

- CVS support and shock

- Blood transfusions and conservation strategies

- Point of Care Coagulation testing

References:

- Lamb, C., MacGoey, P., Navarro, A., & Brooks, A. (2014). Damage control surgery in the era of damage control resuscitation. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 113(2), 242-249. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu233

- Kushimoto, S., Kudo, D. & Kawazoe, Y. Acute traumatic coagulopathy and trauma-induced coagulopathy: an overview. j intensive care 5, 6 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-016-0196-6

- Voelckel WG. Vasopressin in traumatic hemorrhagic shock. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2025 Apr;38(2):81–92. doi:10.1097/ACO.0000000000001456

- Leon D, Levy M, Sikorski R. Calcium and vasopressin adjuncts in bleeding trauma. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2025 Jan 29;15:32.

- MDPI J Clin Med. Rethinking balanced resuscitation in trauma. 2022.

- Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. REBOA for remote damage control. 2025 Apr;38(2):100–106.

- END POINTS OF RESUSCITATION Dr Ahmad Alli. Wits refresher 2013

- Management of the severely injured patient: Current concepts Dr Francois Roodt. UCT refresher 2015

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- ICU One Pager. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://onepagericu.com/

Summaries:

ICU one pager haemorrhagic shock

Massive haemorrhage

NAP 4

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “9048b4e9-b396-4b40-9b78-fa6a2f131b9d”