- Summary

- Etiology

- Clinical Presentation

- Patient Management

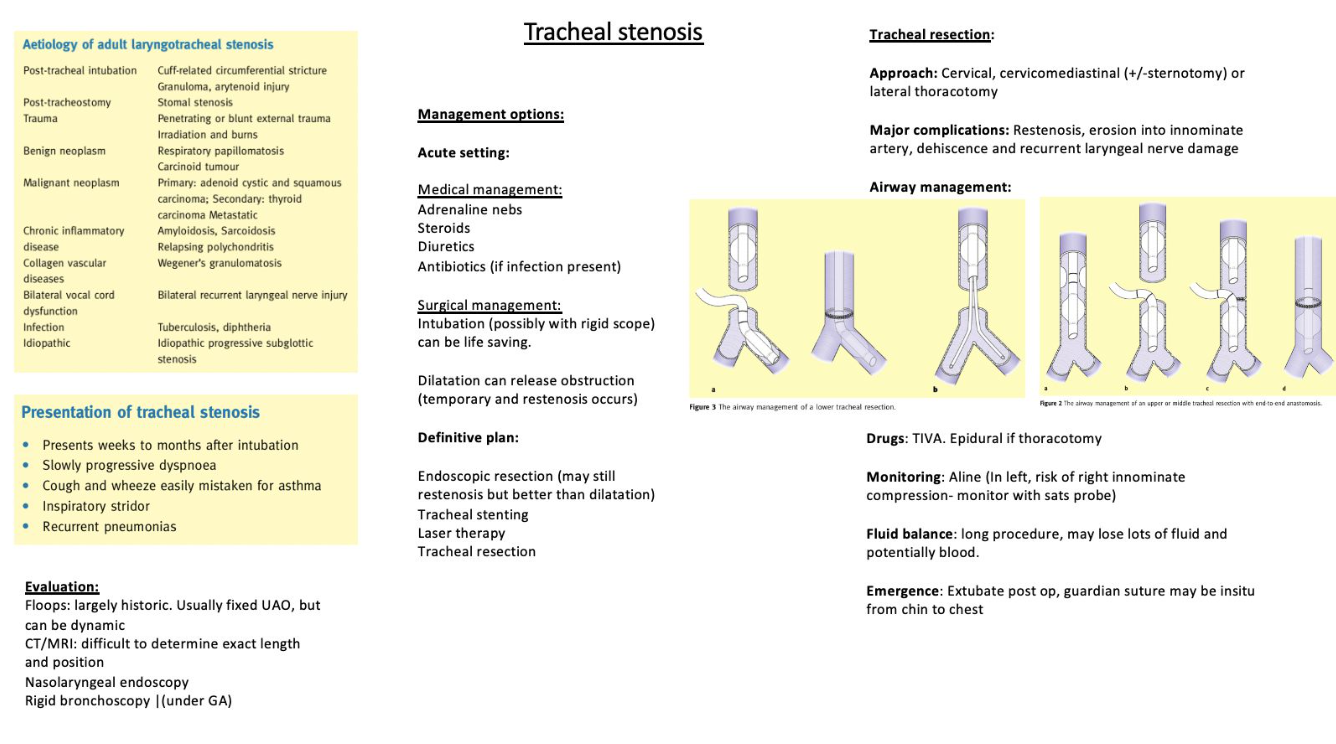

- Anaesthesia for Tracheal Resection

- Ventilation Strategies During the "Open Airway" Phase of Tracheal Resection and Anastomosis

- Extubation and Emergence

- Regional Anesthesia Techniques

- Approach to Tracheal Surgery

- Postoperative Considerations

{}

Summary

Etiology

Adult tracheal stenosis primarily arises from inflammatory lesions (postintubation, traumatic, and infectious) or tumors. The most prevalent cause, accounting for approximately 75% of cases, is postintubation stenosis, despite the reduction in its incidence following the introduction of high-volume, low-pressure tracheal tube cuffs. Contributing factors to postintubation stenosis include:

- Overinflation of tracheal cuff

- Use of large-sized tracheal tubes

- Tube movement in intubated patients (due to bucking, ventilation, and circuit traction)

- Prolonged intubation

- Steroid use, diabetes, hypotension, and infections may also play a role.

Primary tracheal tumors are extremely rare, with squamous cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma being the most common histologic types. Squamous cell carcinoma has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 13%. Secondary tracheal tumors are more common and typically metastatic, originating from the thyroid, lung, esophagus, or breast. Other rare causes of stenosis include compressive lesions such as goiter and vascular lesions, as well as acquired lesions due to traumatic airway injuries, inhalational or surgical trauma.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with tracheal tumors often exhibit an insidious onset of symptoms, which may progress gradually. However, symptoms can also appear suddenly, depending on the underlying pathology. Common symptoms include:

- Cough

- Dyspnea on exertion (most common and correlates with a 50% reduction in tracheal diameter to less than 8 mm)

- Dyspnea at rest (correlates with a 75% reduction in tracheal diameter to less than 5 mm)

- Hoarseness of voice

- Dysphagia

- Stridor (indicating recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement)

Acute exacerbations may occur due to upper respiratory infections. Inflammatory lesions typically have a preceding cause. Patients with a history of intubation or tracheostomy may present with symptoms after a variable interval, necessitating a high index of suspicion. Asthma and cardiac conditions are common differential diagnoses.

Patient Management

Management of patients with tracheal stenosis is tailored according to the etiology and severity of the stenosis. The primary goal is curative treatment or palliation. Available treatment options include:

- Tracheal dilatation with or without stenting

- Irradiation

- Laser ablation

- Tracheostomy

- Resection anastomosis surgery

For patients with moderate to severe obstruction, emergency tracheal dilatation (with or without stenting) or tracheostomy may be required. Bronchoscopy in these cases is typically deferred until it becomes part of the standard treatment protocol.

Patient Selection for Surgery

Ideal surgical candidates possess an operative glottis and resectable lesions. Prolonged positive pressure ventilation is a contraindication due to its negative impact on anastomosis. Therefore, patients requiring postoperative ventilation, such as those with severe pulmonary or neuromuscular dysfunction, are not considered suitable for surgery. Other contraindications and factors increasing surgical risk include:

- Steroid dependence

- History of neck and chest radiation therapy

- Invasive tumors

- Microangiopathies from diabetes mellitus

- High-dose corticosteroid therapy (>10 mg/day of prednisone), with patients requiring weaning for 2-4 weeks before surgery

- Redo surgery

- Resections longer than 4 cm

- Age <17 years

- Diabetes mellitus

- Preoperative tracheostomy

- Laryngotracheal resection

Surgical Considerations

Surgical Approach

The surgical approach is determined by the stenotic segment’s location and the extent of resection required:

- Subglottic and upper tracheal lesions are approached via a cervical/collar incision with the patient supine and neck extended. In cases of subglottic stenosis (1-4 cm in length), segmental resection and primary anastomosis are typically feasible.

- Malignant lesions may necessitate a radical approach (e.g., laryngectomy).

- Mid-tracheal stenosis is approached via a cervico-mediastinal incision, with the cervical incision allowing proximal tracheal access and laryngeal drop mitigating anastomotic stress.

- Carinal lesions require individualized approaches, typically via sternotomy or posterolateral thoracotomy, depending on the extent of resection and whether parenchymal resection is also required.

Key Considerations:

- Tracheal blood supply is segmental, with vessels entering from the lateral aspect. Hence, anteroposterior dissection is favored to avoid vascular compromise.

- Guardian sutures are employed to minimize tension on the anastomosis by maintaining neck flexion postoperatively.

Anaesthesia for Tracheal Resection

Preoperative Evaluation

- Detailed history and physical examination

- Relevant laboratory investigations based on ASA status

- Pulmonary optimization, such as cessation of smoking, nebulization, and steam inhalation, to reduce perioperative morbidity

For patients over 40 years of age or those with significant cardiac risk factors, a cardiology evaluation is recommended, potentially including echocardiography, stress echocardiography, or angiography.

Focus Areas:

- Location and extent of stenosis: History and dyspnea patterns, particularly dyspnea at rest, are crucial in determining stenosis location and constriction diameter.

- Functional classification: Stenosis may be structural or functional. Fixed obstructions of the larynx and upper trachea often present with inspiratory symptoms, while lower airway pathology like dynamic collapse or tracheomalacia manifests as expiratory symptoms.

Imaging and Diagnostic Tools:

- High-resolution CT scan of the neck and thorax with three-dimensional reconstruction

- Fiberoptic bronchoscopy

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

- Pulmonary function tests (PFTs), though these may not consistently quantify obstruction as flow-volume loops are effort-dependent

Bronchoscopy is the most valuable investigation, providing real-time information on stenosis, though the clinical condition can deteriorate between bronchoscopy and surgery. A waiting period of 5-7 days is typically advised for tissue edema to settle post-bronchoscopy before surgery.

Airway Management Strategy

A comprehensive examination, including tracheal palpation and assessment of neck mobility, is vital. The feasibility of bag-mask ventilation should be evaluated, and airway management plans should be prepared in advance. Notably, the patient’s position during the examination is important, as the position allowing the most comfortable breathing should be documented. Patients should be counseled preoperatively regarding postoperative coughing avoidance and the presence of a guardian suture, which limits neck extension after surgery.

Preoperative Preparation and Monitoring

Special Equipment:

- Endotracheal Tubes (ETT): Multiple sizes (2.5 mm to 6.5 mm) are required, especially smaller sizes for varying airway diameters.

- Flexometallic ETT: Necessary for cross-field ventilation.

- Flexible Fiberoptic Bronchoscope (FOB): Both adult and pediatric sizes should be available.

Vascular Access:

- Two wide-bore (18G) intravenous cannulas: These should be secured with extension tubing, as the arms will be hidden under surgical drapes.

- Blood loss: Although typically minimal, ensure adequate venous access for fluid management.

Medications:

- Preoperative dexamethasone: Administered to reduce airway edema due to tissue handling.

Monitoring:

- Standard ASA Monitoring: ECG, SpO2, NIBP, and EtCO2 are typically sufficient.

- Additional Monitoring:

- Intra-arterial catheter: Indicated for cases involving jet ventilation, apneic intervals during tracheal anastomosis, or hemodynamic alterations from cardiac retraction.

- Central venous line: Recommended only for patients with severe cardiomyopathy; should be placed in the femoral or subclavian veins to keep the neck free.

- Anesthesia depth monitor (BIS): Crucial for managing anesthesia depth during intravenous anesthesia.

- Neuromuscular monitoring (TOF): Ensures a motionless surgical field and confirms complete reversal of neuromuscular blockade at the end of the procedure.

- Urine output: Monitors adequate organ perfusion.

Induction and Maintenance

Airway Management:

- Standard Approach: Place the ETT distal to the stenotic segment to maintain airway control.

- Supraglottic Airway Devices (SADs): Effective in cases of severe subglottic stenosis, anticipated difficult intubation, or as a rescue device for failed intubation. SADs can also be beneficial post-anastomosis to reduce stress on the surgical site and prevent bucking on the ETT.

Contraindications for SAD Use:

- Active gastrointestinal bleed

- Tracheal/laryngeal tumors

- Restricted mouth opening (<2 cm)

- Diaphragmatic hernia

- Pregnancy

Induction Strategies:

- Tracheal Diameter >8 mm:

- Standard induction with neuromuscular blockade and endotracheal intubation.

- SAD may be used as an alternative for airway control.

- For tracheostomized patients, induce anesthesia with an intravenous agent (propofol with or without ketamine), and ventilate through the tracheostomy tube, which is later replaced by a reinforced ETT.

- Tracheal Diameter 5-8 mm:

- Use inhalational induction with sevoflurane in oxygen, possibly supplemented with propofol infusion for deeper anesthesia.

- Maintain spontaneous or assisted breathing, with possible bronchoscopy and tracheal dilation immediately after induction. Secure the airway with ETT or SAD.

- Tracheal Diameter <5 mm:

- Perform awake fiberoptic bronchoscopy to secure the compromised airway. Prepare the patient with lignocaine nebulization, intravenous antisialagogue, and spray-as-you-go lignocaine during bronchoscopy.

- After ETT placement past the stenotic segment, administer a muscle relaxant and start positive pressure ventilation. Muscle relaxation is essential to prevent negative pressure pulmonary edema.

Maintenance of Anesthesia:

- Inhalational Agent in Oxygen: Used after establishing airway control.

- Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA): Preferred during the “open airway phase” to ensure consistent anesthesia delivery under changing airway conditions. Spontaneous or controlled ventilation may be employed depending on patient and surgical factors.

Ventilation Strategy:

- Controlled Ventilation: Typically preferred during the “open airway” phase.

- Spontaneous Ventilation: Can be considered with an experienced surgical team and low-risk patients, especially if the lesion is limited to the upper airway and the patient tolerates light sedation without movement.

- Regional or Neuraxial Anesthesia: Supplementation may be required to prevent respiratory splinting, coughing, or movement during spontaneous ventilation.

Pharmacological Management:

- Dexmedetomidine: A viable option during the open airway phase due to its analgesic, anxiolytic, and amnestic properties without significant respiratory depression. It is increasingly being explored as a sole agent for induction and smooth extubation.

Postoperative Considerations

- Cough Avoidance: Instruct the patient to avoid coughing postoperatively to protect the anastomosis.

- Guardian Suture: Implement to prevent neck extension, maintaining the integrity of the tracheal anastomosis.

Ventilation Strategies During the “Open Airway” Phase of Tracheal Resection and Anastomosis

The primary goal during the “open airway” phase of tracheal resection and anastomosis is to ensure adequate and reliable ventilation while maintaining a clear surgical field, minimizing patient movement, and reducing blood and secretion spurts. Several ventilation strategies can be employed, each with its own advantages and limitations.

1. Distal Tracheal Intubation with Cross-Field Ventilation

- Technique: This traditional and widely used approach involves intubating the distal trachea with a sterile reinforced endotracheal tube before tracheal resection. Cross-field ventilation is then performed using a fresh sterile anesthetic circuit placed over the surgical drapes and connected to the anesthesia machine.

- Procedure:

- After securing the distal trachea, the oral endobronchial tube is withdrawn and replaced with a regular-sized endotracheal tube positioned proximal to the stenosis.

- The stenotic segment is resected, and posterior anastomosis is performed using an apnea-ventilation-apnea technique.

- The proximal endotracheal tube is then guided past the anastomotic site, allowing the anterior anastomosis to be completed over the tube.

- In cases involving lower tracheal or carinal tumors, the tube may be placed in the left main bronchus to facilitate resection, followed by repositioning to ventilate the right lung while completing the anastomosis.

- Advantages: Reliable and well-established method, with significant literature supporting its use.

- Disadvantages: Requires multiple tube adjustments and may cause hypercapnia, which is typically managed post-anastomosis.

2. Jet Ventilation

- Technique: Jet ventilation, introduced by Sanders, uses intermittent high-pressure gas jets delivered through a narrow catheter, with expiration being passive. It can be administered at low frequencies (10–20/min) or high frequencies (100–400/min).

- Procedure:

- Low-frequency jet ventilation can be visually monitored by observing chest rise, while high-frequency jet ventilation involves adjusting inspiratory time, frequency, and driving pressure.

- In cases involving the carina, separate catheters may be used for each main bronchus.

- Advantages: Provides a clear surgical field and does not require specialized equipment.

- Disadvantages: Risk of contaminating the distal trachea with blood and debris, auto-PEEP generation, inability to monitor EtCO2 and inspired gases, and potential for tracheal laceration and pneumothorax due to “whip motion” trauma.

3. High-Frequency Positive Pressure Ventilation (HFPPV)

- Technique: HFPPV employs a multi-orifice insufflation catheter at the lower end of the endotracheal tube, delivering minimal tidal volumes (3–5 ml/kg) at a high respiratory rate (up to 60 breaths/min).

- Procedure:

- The low tidal volume allows for a relatively still surgical field, while the high respiratory rate ensures adequate minute ventilation.

- It is particularly useful for allowing complete tracheal anastomosis in one go.

- Advantages: Reduces the risk of whip motion injury and provides stable ventilation without significant movement.

- Disadvantages: Potential for barotrauma, and difficulty in monitoring and quantifying ventilation parameters.

3. LMA and Micro Laryngeal tube/ Reinforced Tube Approach (Prof Ross Hofmeyr)

- Technique: Induce with LMACrossfieldIntubate through LMA for anterior closureRemove Tube to end with LMA

- Procedure:

- Posterior resection and anastomosis will be done under cross-field ventilation

- Anterior anastomosis: Use micro laryngeal or reinforced tube intubate through LMA with scope pass the resection

- Remove ETT from LMA after resection is complete

- Extubate on LMA

4. Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) and Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO)

- Technique: CPB and ECMO provide extracorporeal oxygenation and are particularly useful in complex cases where airway access is severely compromised.

- Indications:

- CPB: Historically used for carinal tumors requiring systemic anticoagulation.

- ECMO (Venovenous or Venoarterial): Safer than CPB, with lower anticoagulation requirements. Indicated for:

- Long-segment tracheoplasty in children

- Combined cardiac and pulmonary procedures in adults with malignancies

- Advanced tracheobronchial trauma

- Occlusive tracheal pathologies that cannot be managed by rigid bronchoscopy or tracheotomy

- Advantages: Provides full respiratory support without obstructing the surgical field and is particularly valuable in high-risk, complex cases.

- Disadvantages: Requires careful management of anticoagulation to prevent complications. Advances in ECMO technology, including peripheral vascular cannulation, have reduced the need for high levels of anticoagulation, minimizing complications.

Comparison of Anesthetic Techniques for Tracheal Surgery

| Anesthesia/Airway Technique | Patient Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Approach General anesthesia with endotracheal intubation and cross-field ventilation Mechanical ventilation |

– Default technique for most patients – Patients with contraindications to regional anesthesia |

– Protects from aspiration – Easy to suction fluid and blood from the lower airway – Secures airway, offers controlled oxygenation/ventilation – Easy to perform anastomotic leak test |

– Surgical exposure compromised by ETT – Possible complications of intubation and mechanical ventilation (airway injury, disruption of friable tissue) – Extubation might disrupt anastomosis – Difficult to visualize vocal cord function |

| Spontaneous Ventilation (Nonintubated) Mild to moderate sedation Regional, neuraxial, or local anesthesia Supraglottic airway device (SAD) |

– Ideally suited for limited extent, benign disease – Small incisions – Experienced surgical team – Patients who can tolerate up to 3h surgery – Good cardiopulmonary function – ASA class 1 or 2 – BMI < 25 kg/m² – No local anesthetic allergy |

– Excellent surgical exposure – Avoids complications of intubation (airway injury and disruption of friable tissue) – Nonintubated trachea is more flexible—facilitates surgical re-approximation – Decreased postoperative complications with residual opioids, anesthetics, and paralytics—early recovery – Allows vocal cords function assessment |

– Ineffective ventilation can cause hypoxemia/hypercarbia – Risk of aspiration – Precise titration of anesthetics to prevent apnea or coughing – Inadequate pain control—patient movement/coughing – Increased risk of regional block complications, block failure, and local anesthetic toxicity – Not possible in sicker patients and/or with extensive lesions |

| Jet Ventilation (General anesthesia) Highor low-frequency jet ventilation |

– Same as for patients with endotracheal intubation and poor surgical visualization | – Improved surgical visualization – Rapid rescue technique – Can augment other airway techniques |

– Difficulty monitoring ventilation – Barotrauma – Mucosal injury (whiplash injury) |

| Extracorporeal Life Support VV-ECMO, VA-ECMO, or CPB |

– Any anesthesia and any airway (including no airway) – Cases with near-total obstruction – Patients with extensive tumor infiltration – Hemodynamically unstable patients |

– Ultimate rescue technique – Provides best surgical exposure – Reliable control of gas exchange – Hemodynamic support |

– Needs to be prepared in advance – Cannulation must be done before starting the case under LA – Issues of coagulopathy – Causes hemodilution – Chances of vascular injury |

This table provides a comprehensive comparison of different anesthetic techniques for tracheal surgery, outlining the patient characteristics suitable for each technique, along with their respective advantages and disadvantages.

Extubation and Emergence

Anastomosis Leak Test

Upon completing the tracheal anastomosis, an “anastomosis leak test” is performed to check the integrity of the anastomosis. This involves subjecting the airway to 20-30 cm H2O of positive airway pressure for about 10 seconds while submerging the anastomosed trachea in saline. Any bubbles would indicate a leak, necessitating further repair.

Extubation

Extubation is generally preferred immediately after surgery unless there are compelling reasons for continued ventilation. Immediate extubation reduces the risk of trauma to the fresh tracheal anastomosis from the endotracheal tube cuff and minimizes the stress of positive pressure ventilation on the suture line.

Steps for Extubation:

- Bronchoscopy: A final bronchoscopy is performed for tracheobronchial toileting and to visually inspect the fresh anastomosis.

- Preventing Bucking and Head Extension:

- Taper off muscle relaxants gradually.

- Ensure good analgesia.

- Use a propofol infusion to maintain smooth emergence.

- Normothermia: Maintain normothermia to prevent shivering, which increases oxygen consumption and respiratory stress.

- Humidified Gases: Administer humidified gases to prevent airway drying and postoperative irritation.

- Gentle Suctioning: After ensuring full recovery from neuromuscular blockade, gentle suctioning is performed before extubation.

- SAD Placement: Alternatively, after extubation, a supraglottic airway device (SAD) may be placed in a spontaneously breathing anesthetized patient, which is removed as the patient fully regains consciousness.

Patient Counseling:

- Preoperatively counsel the patient on the importance of avoiding abrupt neck extension, maintaining the head in a flexed position, and understanding the purpose of the guardian suture during the postoperative period.

Reintubation Considerations

Reintubation post-extubation can be challenging and dangerous due to factors like the flexed neck position, airway edema, and blood in the airway. If reintubation is necessary, it should be performed with a fiberoptic bronchoscope (FOB) to avoid injuring the fresh anastomosis or dislodging any stent.

Postoperative Care

ICU Management

Patients are usually admitted to the ICU for close monitoring of potential complications following tracheal resection and anastomosis.

Monitoring:

- Periodic Blood Gas Analysis: Regular ABG monitoring is essential, especially in the first 24 hours postoperatively.

- Clinical Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of vital signs and respiratory status.

Positioning:

- Head Flexion: Maintain the head flexed at approximately 45° using guardian sutures to minimize tension on the anastomosis and prevent complications.

Pain Management

- Thoracotomy Patients: Patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) is recommended.

- Cervical Incisions: Systemic analgesics are typically sufficient.

- Multimodal Analgesia: Helps prevent patient agitation, delirium, and respiratory depression.

Ancillary Care

- Humidified Oxygen: Prevents drying of the airway.

- Nebulization: Keeps the airway moist and reduces irritation.

- Physiotherapy: Aids in lung expansion and prevents atelectasis.

- Antitussives: Prevent coughing, which could strain the anastomosis.

- Gentle Pulmonary Toileting: Helps remove secretions without causing trauma to the anastomosis.

Complications

Postoperative complications can be classified into surgical and non-surgical categories:

Surgical Complications

- Anastomosis Dehiscence: A serious complication that can lead to airway compromise.

- Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Dysfunction: May result in vocal cord paralysis.

- Hemorrhage: Bleeding at the surgical site.

- Air Leak: Due to incomplete closure of the anastomosis.

- Tracheoesophageal Fistula: Abnormal connection between the trachea and esophagus.

Non-Surgical Complications

- Respiratory Failure: May result from inadequate ventilation or airway obstruction.

- Pneumonia: Common due to impaired airway clearance postoperatively.

- Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis: Risks associated with surgery and immobilization.

- Myocardial Infarction: Especially in patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions.

- Tetraplegia: A rare but severe complication associated with hyperflexion of the neck, leading to compromised spinal cord blood supply. To prevent this, neck flexion should be carefully monitored, and a guardian roll should be used to maintain proper head position.

Regional Anesthesia Techniques

Several regional anesthesia techniques have been explored for tracheal resection and anastomosis, though they are not yet widely adopted as sole techniques:

-

Cervical Epidural Catheters:

- Placement: At the C7/T1 level using 0.5% ropivacaine.

- Supplementation: May require additional local infiltration, airway topicalization, and systemic analgesics.

- Suitability: Best for patients without cardiac conditions and those not requiring sternotomy.

- Risks: Incision on the trachea may cause desaturation, which can be managed with oxygen insufflation through a sterile catheter.

-

Cervical Plexus Block:

- Technique: Bilateral blocks with 7 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine under ultrasound guidance.

- Supplementation: Often requires intravenous analgesics and/or sedatives. In some cases, LMA insertion or intubation may be necessary.

-

Local Infiltration:

- Technique: Stepwise infiltration by the surgeon using local anesthetic, supplemented with analgesia and sedation (e.g., fentanyl, ketamine, midazolam).

- Suitability: Described in cases like subglottic hamartoma.

-

Thoracic Epidural:

- Placement: At the T7/T8 level.

- Supplementation: Requires additional IV opioids, intercostal nerve blocks, and sedation. LMA is used for airway management, with oxygen insufflation for distal trachea.

Approach to Tracheal Surgery

Preoperative Considerations

-

Right Place

- Plan the theatre layout and ensure the operating table is properly arranged for optimal surgical and anesthetic access.

-

Timing and Optimization

- Patient Characteristics:

- Patients often have a history of smoking, alcohol use, and comorbidities.

- Medical Optimization:

- Chronic airway narrowing may not present with overt stridor or distress at rest due to adaptation.

- Acute Optimization:

- Preoperative interventions include:

- Steroids, nebulized adrenaline, beta agonists, and anti-sialogogues.

- Heliox:

- Reduces work of breathing by decreasing turbulent flow and airway resistance but is limited in acutely hypoxemic patients.

- High-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) is beneficial for oxygenation.

- Preoperative interventions include:

- Patient Characteristics:

-

Assessment and Investigation

- Review imaging:

- Chest X-rays and CT scans for airway anatomy and pathology.

- Use flexible nasendoscopy to assess dynamic airway narrowing (e.g., posterior glottis).

- Repeat dynamic nasendoscopy just before surgery to update airway status.

- Consider airway ultrasound to mark the cricothyroid membrane (CTM).

- Understand the degree, type, and level of airway narrowing to plan the airway management approach.

- Note: Visualization with flexible endoscopy does not always predict successful ventilation or similar laryngoscopic views under general anesthesia (GA).

- Review imaging:

-

Personnel

- Ensure a coordinated team approach:

- All personnel (surgeons, anesthetists, assistants) must understand the stepwise strategy for airway management, including backup plans.

- Ensure a coordinated team approach:

Intraoperative Considerations

-

Team Approach

- A well-coordinated team effort is critical, especially in shared airway surgeries.

-

Approach to the Airway

- Tracheal Intubation:

- Use a narrow-bore microlaryngeal tube (MLT), flexometallic tube, or laser-resistant tube depending on the surgical needs.

- MLT sizes range from 4.0 mm with a preserved cuff length (~31 cm).

- Conventional Ventilation:

- Narrow ETTs generate higher driving pressures.

- Lower inspiratory-to-expiratory (I:E) ratios are often required to allow adequate expiration.

- Be cautious of the “cork in bottle” phenomenon, where a narrowed airway can precipitate complete occlusion.

- Awake Fibre-Optic Intubation (AFOI):

- Often the preferred approach for patients with severe airway narrowing:

- Awake videolaryngoscopy-assisted intubation may be an alternative to AFOI.

- Hyper-angulated devices (e.g., video stylets) reduce laryngoscopic force, create space, and enable atraumatic ETT passage.

- Oxygenation strategies during awake techniques:

- High-Pressure Source Ventilation (HPSV).

- Apneic oxygenation or maintenance of spontaneous ventilation.

- Often the preferred approach for patients with severe airway narrowing:

- Tracheal Intubation:

-

Tubeless Field Techniques

- Tubeless techniques are used to optimize surgical access to the airway.

Jet Ventilation/High-Pressure Source Ventilation (HPSV)

- Used with a rigid surgical bronchoscope to provide unobstructed access to the surgical field.

- Risks:

- Barotrauma, hypercarbia, and inability to monitor ETCO₂.

- Strategies:

- Use the lowest driving pressure to minimize complications.

- Risks:

Manual Jet Ventilation

- Delivered via devices like the Sanders injector or Manujet (fixed pressure).

Automated Jet Ventilation

- Systems such as Monsoon or Mistral include:

- Airway pressure monitoring.

- Automatic cut-off for high airway pressures.

- ETCO₂ monitoring.

Various Routes of Jet Ventilation

- Supraglottic Jet Ventilation:

- Minimal displacement of the vocal cords, suitable for smaller airways.

- May impede expiration in stenotic patients.

- Transglottic Jet Ventilation:

- Specialized catheters (e.g., Hunsaker Mon-Jet) allow FiO₂ delivery and ETCO₂ monitoring.

- Transtracheal Jet Ventilation:

- Performed via a cricothyroid puncture (e.g., Ravussin cannula) under GA or awake.

Spontaneous Ventilation

- Maintains negative intrathoracic pressure, beneficial for managing distal airway pathologies or foreign body removal.

Apnoeic Oxygenation

- Allows a completely still surgical field but risks hypercarbia and acidosis.

Postoperative Considerations

- Monitoring and Observation

- Monitor for:

- Postoperative airway edema.

- Bleeding or obstruction.

- Oxygenation and ventilation status.

- Monitor for:

- Pain Management

- Use multimodal analgesia to minimize coughing and agitation, which could disrupt airway integrity.

- Respiratory Support

- Provide humidified oxygen.

- Use CPAP or BiPAP if required for oxygenation and ventilation support.

- ICU Care

- High-risk patients may require transfer to a high-dependency or intensive care unit for close monitoring.

- Physiotherapy

- Encourage early mobilization and breathing exercises to prevent atelectasis or other pulmonary complications.

Links

- Tracheostomy

- Awake tracheostomy and intubation

- Anaesthesia and cancer surgery

- Shared airway

- ENT surgery and emergencies

- Head and neck surgery

- Airway guidelines

References:

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- Pearson, K. and McGuire, B. (2017). Anaesthesia for laryngo-tracheal surgery, including tubeless field techniques. BJA Education, 17(7), 242-248. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkx004

- Marwaha, A., Kumar, A., Sharma, S., & Sood, J. (2022). Anaesthesia for tracheal resection and anastomosis. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology, 38(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.4103/joacp.joacp_611_20

Summaries:

Awake intubation

AFOI

MaxFax

DAS guidelines

Thrive

Anaesthesia for bronchoscopy-videos

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “fd38054f-ff28-485b-9cdf-9bcacfa40bb6”