{}

Summary

Risk Stratification

- Revised Baux score (rBaux) = Age (yr) + % Total Body Surface Area (TBSA) ± 17 (inhalation injury).

- rBaux < 60 → mortality < 5 %

- rBaux 60–90 → 10–20 %

- rBaux > 110 → > 80 % mortality.

- Contemporary studies confirm three independent mortality predictors: age > 50 yr, TBSA > 20 %, and inhalation injury

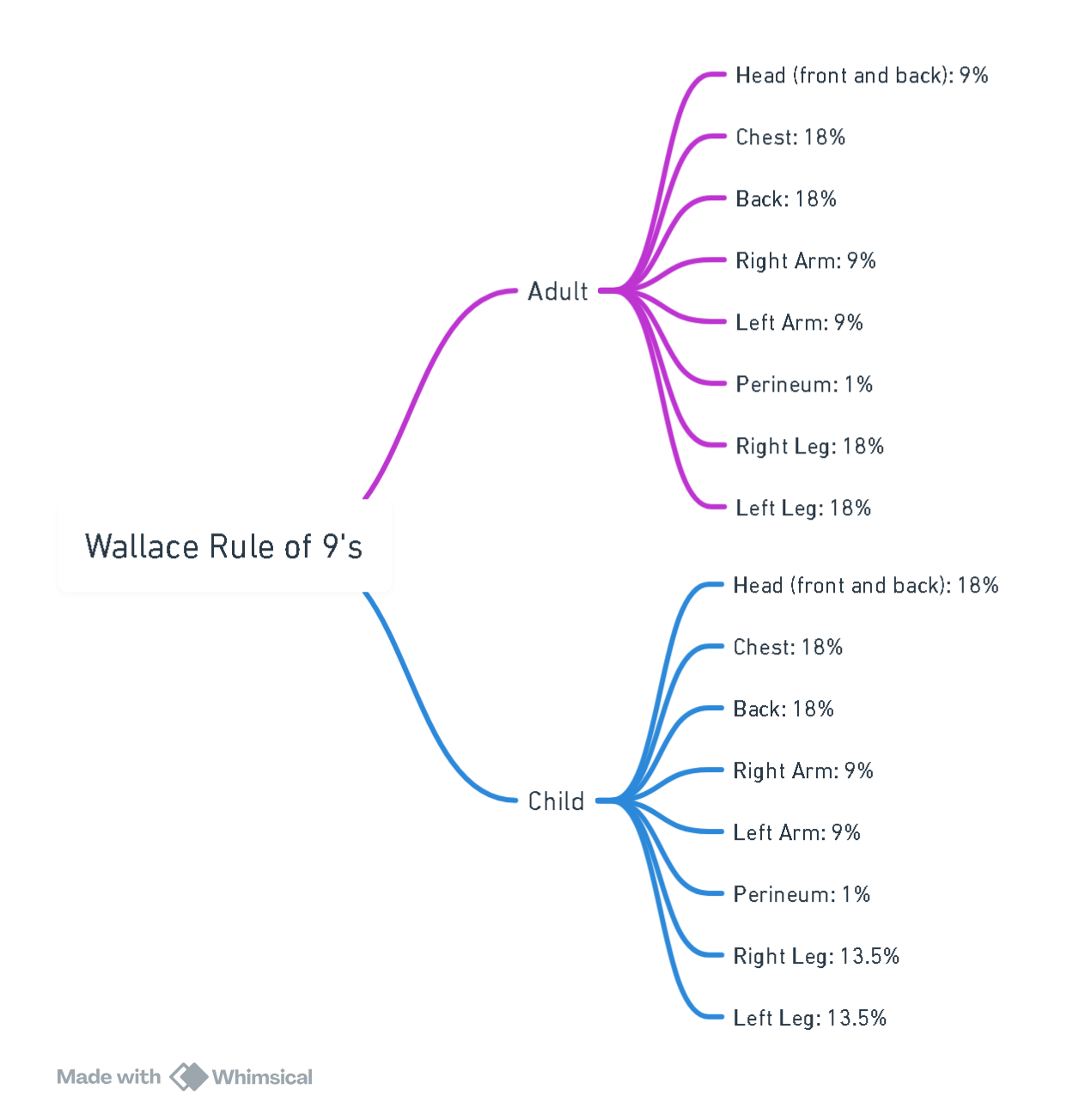

Assessment of Burn Area

Wallace “Rule of Nines” (adult)*

| Region | %TBSA |

|---|---|

| Head & Neck | 9 |

| Each Upper Limb | 9 |

| Anterior Trunk | 18 |

| Posterior Trunk | 18 |

| Each Lower Limb | 18 |

| Perineum | 1 |

- *Adjust for pregnancy (add 3 % to anterior trunk) and obesity (use Lund–Browder chart).

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Lund–Browder Chart

- Preferred for all major burns; essential in children and extremes of body habitus. Dedicated smartphone calculators (e.g., BurnCalc SA) improve accuracy and documentation.

- Only partial and full-thickness areas are included in %TBSA calculations.

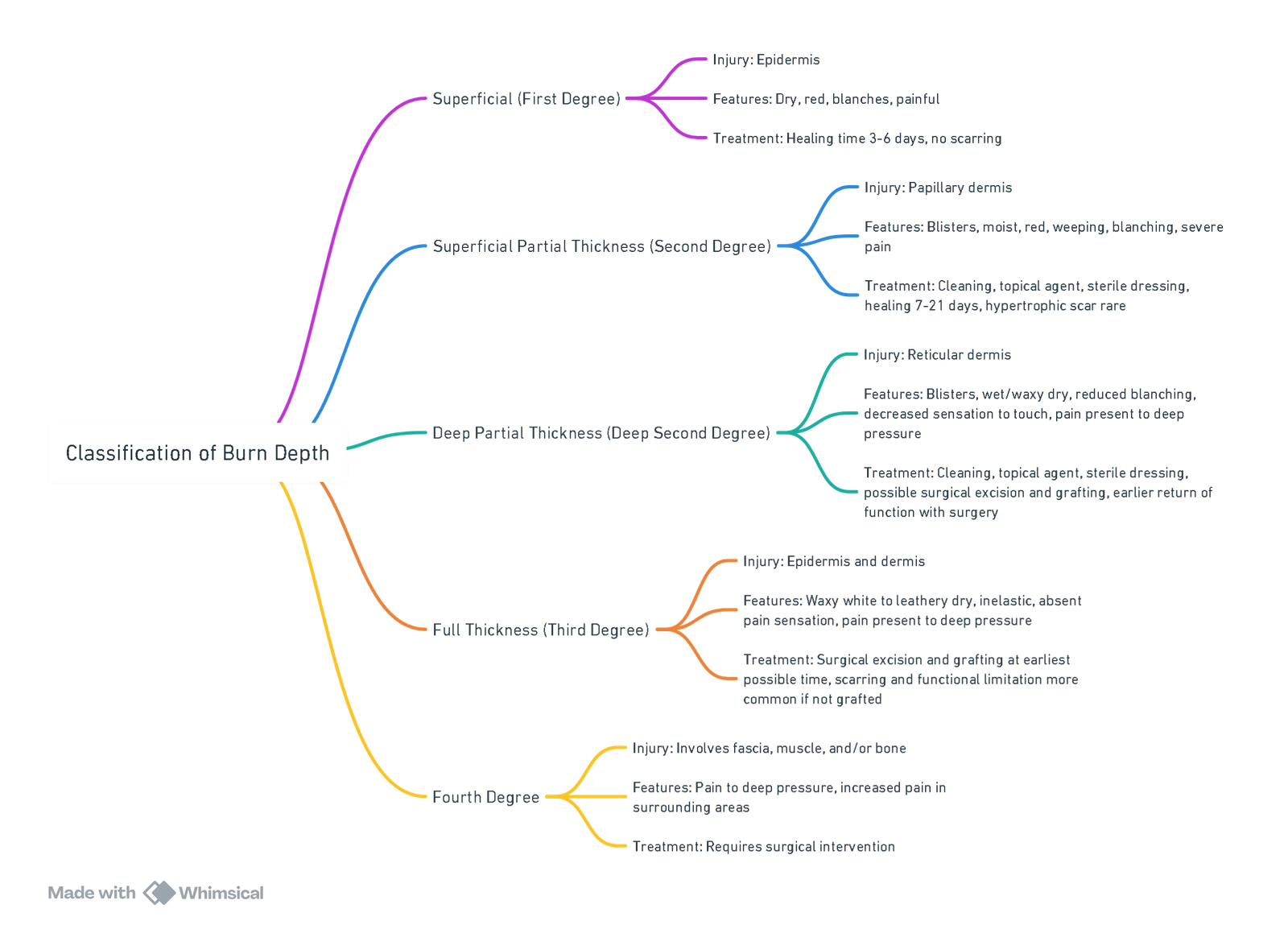

Depth of Burn

| Depth | Skin layers | Typical appearance | Sensation | Healing / management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial (first-degree) | Epidermis | Erythema, no blisters | Painful | ≤ 7 days, no scarring |

| Superficial partial-thickness | Epidermis + superficial dermis | Blisters, blanching pink base | Very painful | 2–3 weeks, minimal scar |

| Deep partial-thickness | Deep dermis | Mottled, sluggish blanch | Dull/pressure pain | ≥ 3 weeks, often graft |

| Full-thickness (third-degree) | Entire dermis ± subcutis | Leathery, white/charred, non-blanching | Insensate | Surgical excision & graft |

| Fourth-degree | Muscle, fascia, bone | Charred, exposed structures | Insensate | Excision, reconstruction |

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

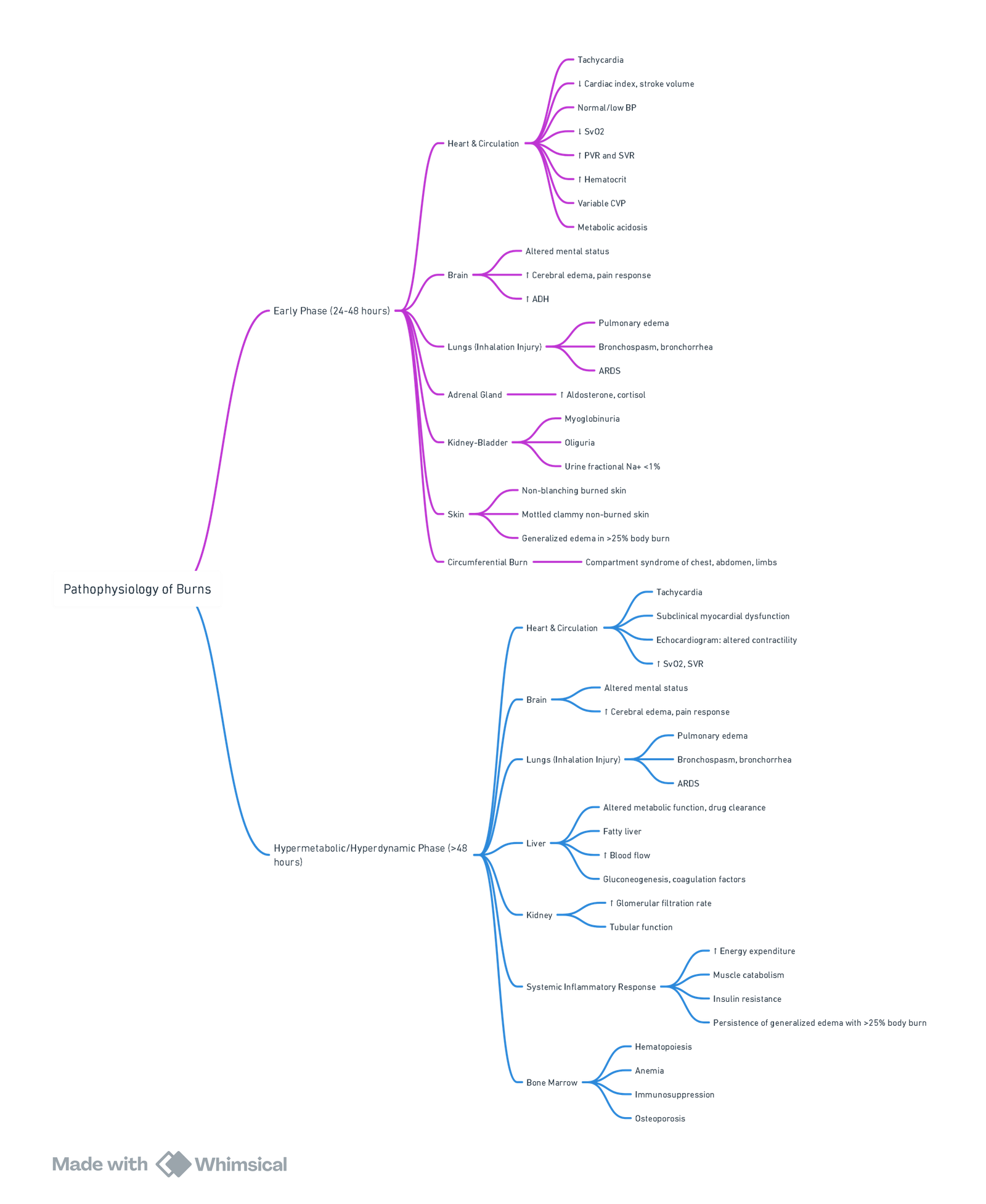

Pathophysiology

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Burn Shock (0–48 h)

- Capillary permeability ↑ within minutes; plasma, albumin and electrolytes leak into interstitium in both burned and unburned tissues once injury ≥ 20 % TBSA.

- Combination of absolute hypovolaemia and ↑ systemic vascular resistance → ↓ cardiac output despite preserved preload.

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α), catecholamines and vasopressin drive vasoconstriction; myocardial depression peaks at 12–24 h.

- Untreated, global tissue hypoxia leads to metabolic acidosis and multi-organ dysfunction.

Hypermetabolic & Hyperdynamic Phase (48 h–>12 months)

- Resting energy expenditure may double; driven by catecholamine surge, insulin resistance and persistent inflammation.

- Clinical features: tachycardia, hyperthermia, muscle catabolism, impaired immunity.

- Attenuated by early excision/grafting, tight glycaemic control, propranolol and anabolic agents (e.g., oxandrolone).

Inhalation Injury

| Component | Key points |

|---|---|

| Supraglottic thermal injury | Stridor develops early; anticipate airway oedema in enclosed-space fires. |

| Subglottic chemical injury | Toxic particulates impair mucociliary clearance → bronchospasm, cast formation, V/Q mismatch. |

| Systemic poisoning | Carbon monoxide (CO) & hydrogen cyanide interfere with O₂ transport and utilisation. |

Management Pearls of Inhalational Injury

- Early airway control if hoarseness, stridor, or TBSA > 40 %.

- Fibre-optic bronchoscopy within 24 h grades injury and guides therapy.

- 100 % O₂ until carboxyhaemoglobin < 5 %. Hydroxocobalamin reserved for confirmed cyanide toxicity because of AKI risk.

- Nebulised “burn cocktail” (N-acetylcysteine + heparin + salbutamol q4 h) shortens ventilation duration in moderate–severe injury.

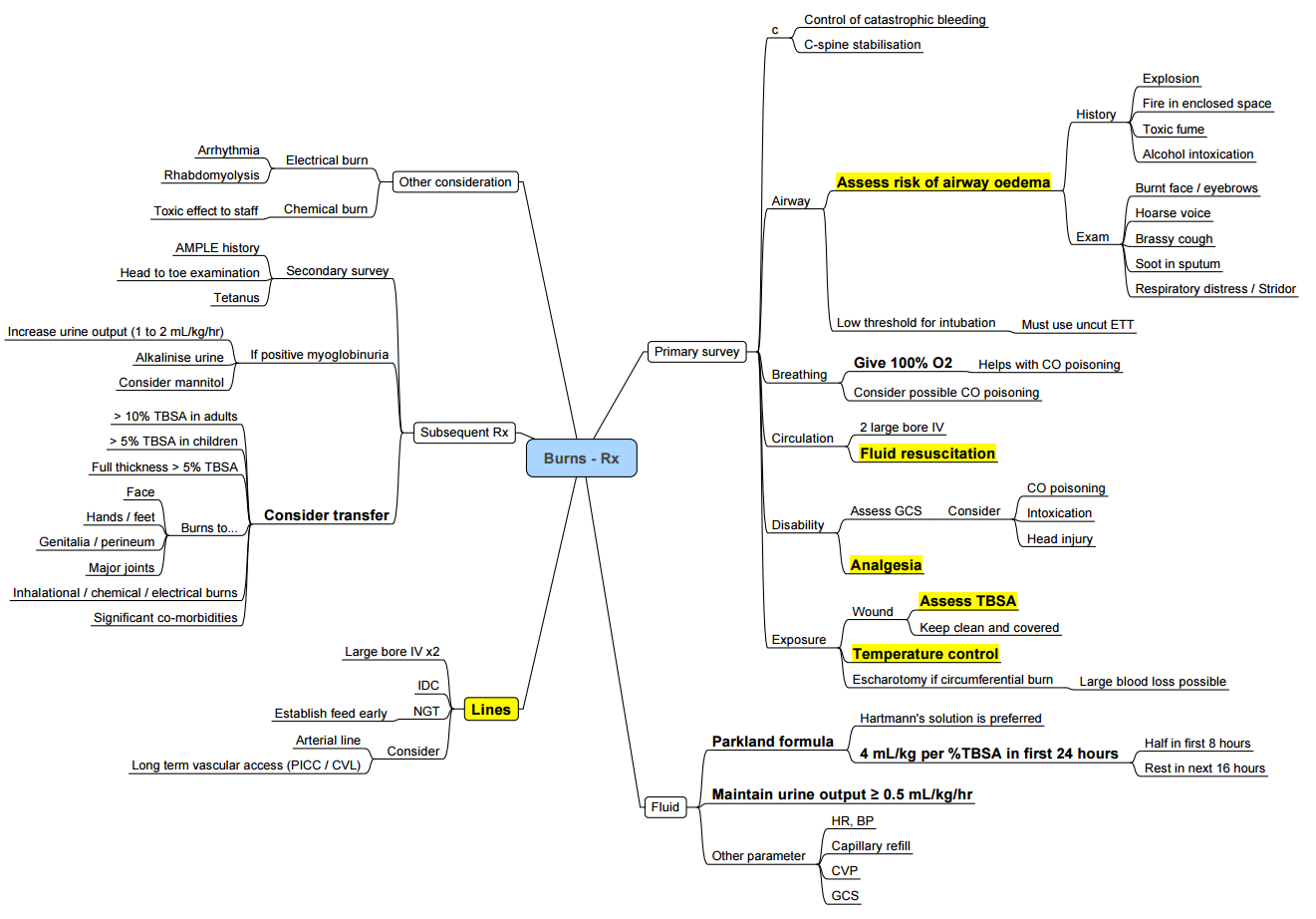

Fluid Resuscitation (first 48 h)

- Burns <15% TBSA:

- Managed with oral or intravenous fluid administered at 1.5 times the maintenance rate.

- Careful attention to hydration status is essential.

Initial Prescription (adult Burns ≥ 20 % TBSA)

| Formula | First-line volume | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Modified Brooke (ABA 2023) | 2 mL kg⁻¹ % TBSA Lactated Ringer’s in first 24 h | Lower volumes reduce “fluid creep”. |

| Parkland | 4 mL kg⁻¹ % TBSA LR | Still acceptable where monitoring robust. |

- Give ½ in first 8 h (from time of burn), remainder over next 16 h; adjust hourly to maintain urine output 0.5–1.0 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (1 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ in children).

Fluid Choice

- Balanced crystalloids (LR or Plasma-Lyte) preferred; avoid large-volume normal saline to limit hyperchloraemic acidosis.

- Colloid (5 % albumin): consider after 12–24 h or when crystalloid requirement > 250 mL kg⁻¹; evidence shows ↓ total volume but no mortality signal.

- Hypertonic saline, hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin are not recommended.

Adjuncts & Emerging Therapies

| Therapy | Evidence | Practical notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-dose vitamin C (66 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ for 24 h) | Reduces fluid need & weight gain in small studies; ongoing multicentre VICToRY trial. | Monitor renal function; risk of oxalate nephropathy. |

Monitoring & Endpoints

- Urine output, lactate (< 2 mmol L⁻¹ by 12 h), base deficit (< 4 mmol L⁻¹), mean arterial pressure ≥ 65 mmHg, Cap refil <3 sec

- Point-of-care ultrasound (IVC variability, stroke volume) and intra-abdominal pressure help detect occult hypovolaemia or over-resuscitation.

Indicators of Adequate Resuscitation

- UO 0.5–1 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (adult).

- Normalising lactate & base deficit.

- MAP ≥ 65 mmHg with decreasing vasopressor requirement.

- Improving mental status and peripheral perfusion (cap refil).

Blood Management

- TBSA > 20 % and deep-dermal injury often develop haemolytic anaemia; transfuse packed red cells to keep Hb > 7 g dL⁻¹ (10 g dL⁻¹ if ongoing hypoxaemia or myocardial ischaemia).

- Screen daily for myoglobinuria in electrical burns; treat with aggressive crystalloid ± mannitol (0.5 g kg⁻¹) and urine alkalinisation.

Key Messages

- Use rBaux to stratify risk and inform counselling.

- Accurately calculate %TBSA with Lund–Browder (apps improve reliability).

- Start LR at 2 mL kg⁻¹ %TBSA and titrate to physiology; avoid “fluid creep”.

- Anticipate airway problems and systemic toxins in inhalation injury.

- Early excision, infection control and metabolic modulation are essential to blunt long-term hypermetabolism.

Anaesthesia for Burn Excision & Skin Grafting

Overall Goals

- ATLS-based primary survey and definitive airway where indicated (facial/neck burns, inhalation injury, TBSA > 40 %).

- Precise burn assessment (TBSA, depth, rBaux) to estimate fluid, blood and metabolic requirements.

- Physiology-guided resuscitation using balanced crystalloids, goal-directed techniques and avoidance of fluid creep.

- Temperature homeostasis—theatre ≥ 32 °C, active warming, warmed fluids.

- End-organ protection: lung-protective ventilation (tidal volume 6 mL kg⁻¹ IBW, PEEP 8–12 cmH₂O), urine output > 1 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹, lactate trending.

- Multimodal analgesia & sedation adjusted for opioid tolerance, anxiety and post-traumatic stress.

- Early nutrition & infection prevention to blunt hyper-catabolism and sepsis risk.

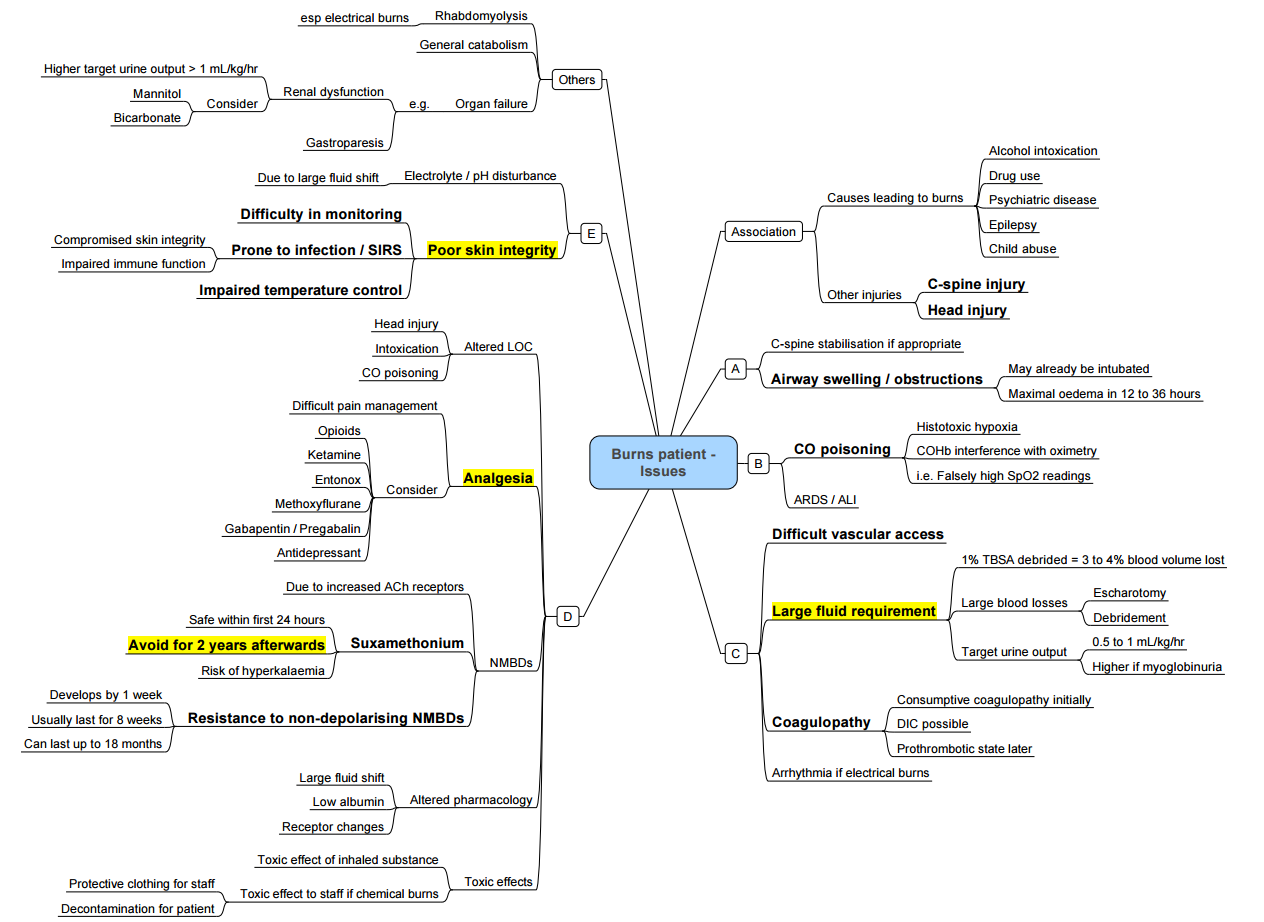

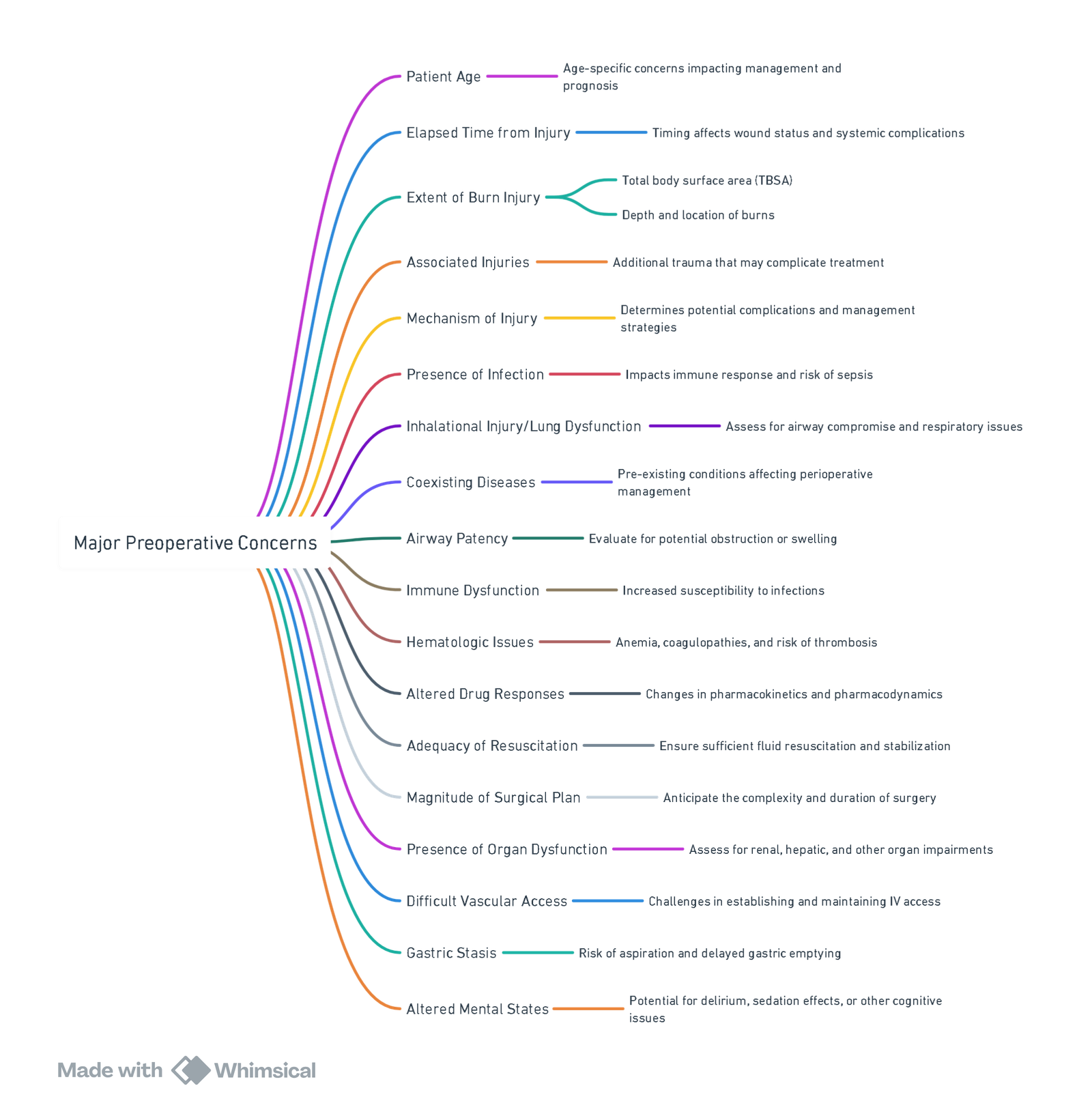

Major Preoperative Concerns

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Pre-operative Assessment

| Item | Key points |

|---|---|

| Airway | Anticipate oedema, secretions, neck contracture → plan videoor fibre-optic intubation; secure tube with cloth ties/arches. |

| Burn severity | %TBSA, depth, time since injury, rBaux score, presence of inhalation injury (bronchoscopy). |

| Resuscitation status | Review last 24 h fluids, urine output, electrolytes, base deficit; exclude abdominal compartment syndrome. |

| Comorbidities & drugs | CO-morbidity (CO poisoning, AKI, arrhythmias), chronic opioids, β-blockers, anticoagulants. |

| Haematology | Baseline Hb & coagulation; arrange type-specific blood, TXA protocol, cell-saver if > 10 % TBSA excision. |

| Vascular access | 2 large-bore peripheral lines ± central line; IO as rescue. |

| Limited fasting | High metabolic rate → keep enteral feeds running to theatre when feasible. |

Anaesthetic Workflow

At Induction

| Aspect | Best practice |

|---|---|

| Airway | Ketamine 1–2 mg kg⁻¹ IV or etomidate 0.2 mg kg⁻¹ if shock; video-scope ready; smaller ETT. |

| Neuromuscular block | Succinylcholine contraindicated ≥ 24 h post-burn → risk of hyperkalaemia. Use rocuronium 1.2–1.5 mg kg⁻¹; expect 50–100 % ↑ dose requirement after day 7; monitor TOF, consider high-dose sugammadex. |

| CO-oximetry | Measure carboxy and methaemoglobin before incision; treat COHb > 10 % with 100 % O₂ or HBO. |

Intra-operative Management

| Domain | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Ambient 32–34 °C, forced-air blanket, fluid warmers; aim ΔT < 1 °C. |

| Fluid & blood | • Start LR 2 mL kg⁻¹ %TBSA (for excision < 6 h). • Goal-directed boluses guided by PPV/∆SV or Doppler; avoid > 5 mL kg⁻¹ h maintenance. • Tranexamic acid 15 mg kg⁻¹ IV + 1 mg kg⁻¹ h cuts blood loss and transfusion (class I evidence). |

| Ventilation | TV 6 mL kg⁻¹ IBW, PEEP 8–12 cmH₂O; recruitment manoeuvres; FiO₂ < 0.6 if PaO₂ adequate; permissive hypercapnia unless TBI present. |

| Analgesia | • Fentanyl ± ketamine infusion 0.1–0.3 mg kg⁻¹ h. • IV lidocaine bolus 1.5 mg kg⁻¹ then 1.5 mg kg⁻¹ h reduces opioid need 25–40 %. |

| Regional | Thoracic epidural / paravertebral for trunk grafts; fascia-iliaca or ESP catheters for limbs; continue intra-op for analgesia, sympathetic control and reduced blood loss. |

| Vaso-active agents | Noradrenaline 0.02–0.1 µg kg⁻¹ min titrated; avoid phenylephrine-only strategy (risk of gut hypoperfusion). |

Pharmacokinetic Considerations (hyperdynamic Phase ≥ 48 h)

- Propofol: clearance ↑; may need 25–50 % higher infusion.

- Opioids: tolerance common; rotate drugs (fentanyl → hydromorphone → methadone).

- NDMRs: receptor up-regulation, ↑ AAG binding and ↑ clearance cause resistance. Monitor TOF every 15 min.

Post-operative Priorities

| Focus | Actions |

|---|---|

| Extubation | Delay if airway oedema, large TBSA, inhalation injury or repeated returns to theatre. |

| Critical care | Continue lung-protective ventilation, titrate fluids to lactate/EVLW, maintain normothermia. |

| Analgesia & sedation | PCA opioids, ketamine 0.1–0.2 mg kg⁻¹ h, dexmedetomidine 0.2–0.7 µg kg⁻¹ h; gabapentin 300 mg q8h; consider low-dose methadone for tolerance. |

| DVT prophylaxis | Enoxaparin 40 mg SC q12 h (adjust for weight/renal). |

| Nutrition & metabolism | Enteral feeds within 6 h; propranolol 1 mg kg⁻¹ d in divided doses to blunt catecholamine-driven hyper-metabolism. |

| Psychological support | Early involvement of mental-health team; screen for acute stress disorder. |

Sedation & Analgesia Algorithm (ICU)

| Phase | Background anxiety | Background pain | Procedural (dressing) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventilated, first week | Midazolam or dexmedetomidine infusion | Morphine/hydromorphone infusion | Midazolam + ketamine or propofol bolus; TXA infiltration at donor site |

| Awake/HDUs | Dexmedetomidine or oral lorazepam | Oral morphine or methadone | IV ketamine 0.5 mg kg⁻¹ + regional block |

Key Points

- Anticipate difficult airway—secure early, avoid adhesive tape.

- Use balanced crystalloids, TXA and goal-directed monitoring to curb fluid creep and blood loss.

- Protect lungs: low VT, moderate PEEP, aggressive physiotherapy.

- Succinylcholine is unsafe after 24 h; NDMR resistance grows from day 3.

- Lidocaine infusion and regional techniques give opioid-sparing analgesia.

Burn Centre Referral Criteria (ABA 2022)

- Refer adults or children with ANY of:

- Partial-thickness burns > 10 % TBSA.

- Burns of face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints.

- Any full-thickness burn > 5 % TBSA.

- Electrical (including lightning) or chemical burns.

- Inhalation injury or circumferential chest/extremity burns.

- Associated trauma or comorbidity increasing complexity (e.g., polytrauma, pregnancy).

- Extremes of age (< 10 y or > 60 y).

- Patients requiring specialised rehabilitation, psychosocial or long-term scar management.

Electrical Injury

- Electrical burns cause multi-system injury that frequently extends well beyond visible skin damage. Management therefore hinges on early identification of occult complications—especially cardiac arrhythmias, deep-tissue necrosis with rhabdomyolysis, and compartment syndromes—and on timely referral to a specialist burn service.

Classification & Pathophysiology

| Voltage | Typical source | Principal hazards |

|---|---|---|

| Low voltage (< 1000 V) | Domestic (110–240 V) | Brief contact → ventricular fibrillation, tetanic contractions → falls / trauma. |

| High voltage (≥ 1000 V) | Industrial lines, substations | Deep tissue heating along current path: bone ↦ muscle ↦ skin; massive myonecrosis, compartment syndrome, rhabdomyolysis. |

| Lightning (≈ 100 million V, μs) | Atmospheric | Massive sympathetic surge, immediate asystole/respiratory arrest, flash burns. |

- Heat is greatest in bone (high resistance), so overlying muscle, neurovascular bundles and skin may be destroyed while cutaneous injury appears trivial.

Cardiac Complications

- Incidence: immediate arrhythmias occur in ≈ 15 % of patients; delayed clinically significant dysrhythmias after a normal initial ECG are rare (< 1 %).

- High-risk features for monitoring ≥ 12 h

- High-voltage exposure, transthoracic current path, loss of consciousness, chest pain, initial ECG abnormality, or cardiac arrest.

- Evaluation: 12-lead ECG, troponin, continuous telemetry (at least 4 h for low-risk, 12–24 h for high-risk).

- Treat per ACLS; pulseless VT/VF is the commonest fatal rhythm.

Musculoskeletal & Renal Sequelae

| Complication | Mechanism | Key actions |

|---|---|---|

| Deep muscle necrosis & compartment syndrome | Joule heating of bone/muscle; oedema in tight fascial compartments | Serial limb exams, compartment pressure > 30 mmHg → urgent fasciotomy (ideally < 6 h). |

| Rhabdomyolysis & myoglobinuria | Massive myocyte breakdown; creatine kinase often > 5000 IU L⁻¹ | • Start balanced crystalloids 10–15 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (typical 500–1000 mL h⁻¹) aiming UO 2 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹. • Alkalinise urine (NaHCO₃ to keep pH > 6.5). • Mannitol 0.25–0.5 g kg⁻¹ if oliguria persists. • Haemofiltration for refractory hyperkalaemia or AKI. |

Definitive Management Algorithm

- ATLS primary survey—assume combined burn-trauma until proven otherwise.

- Cardiac monitoring & ECG (see risk stratification above).

- Resuscitation

- High-voltage injuries: start LR 2 mL kg⁻¹ %TBSA h⁻¹ or 500 mL h⁻¹ until formal calculation; titrate to urine output.

- Add fluids aggressively if pigmenturia or CK > 5000 IU L⁻¹.

- Labs every 2–4 h: FBC, renal profile, CK, lactate, coagulation.

- Early surgical review—fasciotomy/escharotomy within hours if pressures rising or pulses vanish.

- Tetanus, analgesia, psychosocial support.

- Specialist referral (see criteria below).

Key Messages

- A normal ECG after low-voltage shock predicts safety; high-voltage or symptomatic patients need prolonged monitoring.

- Treat high-voltage injuries like hidden crush injuries—anticipate compartment syndrome and rhabdomyolysis.

- Maintain urine output ≥ 2 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ with balanced crystalloids; add bicarbonate and mannitol in dark urine or rising CK.

- Early fasciotomy saves limb and life—do not wait for the “5 P’s”.

- Follow ABA criteria to ensure timely transfer to a specialist burn unit.

Links

Past Exam Questions

Burns and Anaesthesia

A 45-year-old female patient sustained open flame burns to her chest, back, and most of the upper limbs and face after being trapped in a high-rise building. The incident occurred 7 days ago, and she is scheduled for re-debridement of her wounds and a dressing change.

a) Estimate the percentage burns that this patient has sustained. Show calculation. (2)

b) Why may ventilation of this patient be problematic? (2)

c) List two surgical complications of excessive fluid resuscitation. (2)

d) Which two complications of burns injury make the interpretation of haemodynamic indices challenging? (2)

e) Apart from inadequate fluid resuscitation, give two reasons why this patient may develop acute kidney injury. (2)

References:

- Bittner, E. A., Shank, E. S., Woodson, L. C., & Martyn, J. A. J. (2015). Acute and perioperative care of the burn-injured patient. Anesthesiology, 122(2), 448-464. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000000559

- McGovern, C. O., Puxty, K., & Paton, L. (2022). Major burns: part 2. anaesthesia, intensive care and pain management. BJA Education, 22(4), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2022.01.001

- Cartotto R, Johnson LS, Savetamal A, et al. American Burn Association Clinical Practice Guidelines on Burn Shock Resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2023;XX:1-25. ACH PCCG

- Lam NN, Minh NTN. Risk factors for death and prognostic value of revised Baux score for burn patients with inhalation injury. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2022;35(1):41-45. PMC

- Warby R, Maani CV. Burn Classification. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. NCBI

- Burn Fluid Resuscitation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. NCBI

- Beeson T. Updated considerations for intravenous fluid resuscitation. ACEP Critical Care Section Newsroom. 2025 Jan 2. ACEP

- Malkoc A, Jong S, Fine K, et al. High-dose intravenous versus low-dose oral vitamin C in burn care: potential protective effects in the severely burned. Ann Med Surg (Long). 2023;85(5):1523-1526. PMC

- Hanna J, Bezuidenhout H. Low-voltage electrical injuries and the electrocardiogram: is a normal ECG sufficient for safe discharge? Emerg Med J. 2023;40:845-851. PubMed

- Electrical injuries and lightning strikes: evaluation and management. Up-to-date. Wolters Kluwer; 2024. [Up-to-date](https://www.uptodate.com/contents/electrical-injuries-and-lightning-strikes-evaluation-and-management?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Electrical Injury Practice Management Guideline. Updated Oct 2024. Vanderbilt University Medical Center

- Stanley M, Chippa V, Adigun R. Rhabdomyolysis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated Dec 2024. NCBI

- Zhang Y, Li X. Advances in rhabdomyolysis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. J Transl Med. 2025;23:112. ScienceDirect

- American Burn Association. One-page Guidelines for Burn Patient Referral. November 2022. ameriburn.org

- Joint Trauma System. Burn Care Clinical Practice Guideline. 10 June 2025

- Vanderbilt Burn Center. Adult Inhalation Injury Guideline. Revised June 2023. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville. Vanderbilt University Medical Center

- Milton-Jones H, Soussi S, Davies R, et al. An international RAND/UCLA expert panel to determine the optimal diagnosis and management of burn inhalation injury. Crit Care. 2023;27(1):459. PubMed

- Metabolic response to burn injury: a comprehensive bibliometric study. Front Med. 2024;11:1451371. Frontiers

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

Burns

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “e53114a8-e468-429a-b3ac-8ca9aac20b2c”