- Summary

- Burns in Children: Key Concepts

- Classification of Burns

- Physiological Changes in Burns

- Peri-operative Management of Burns in Children

- Pain Management in Paediatric Burn Patients

- Links

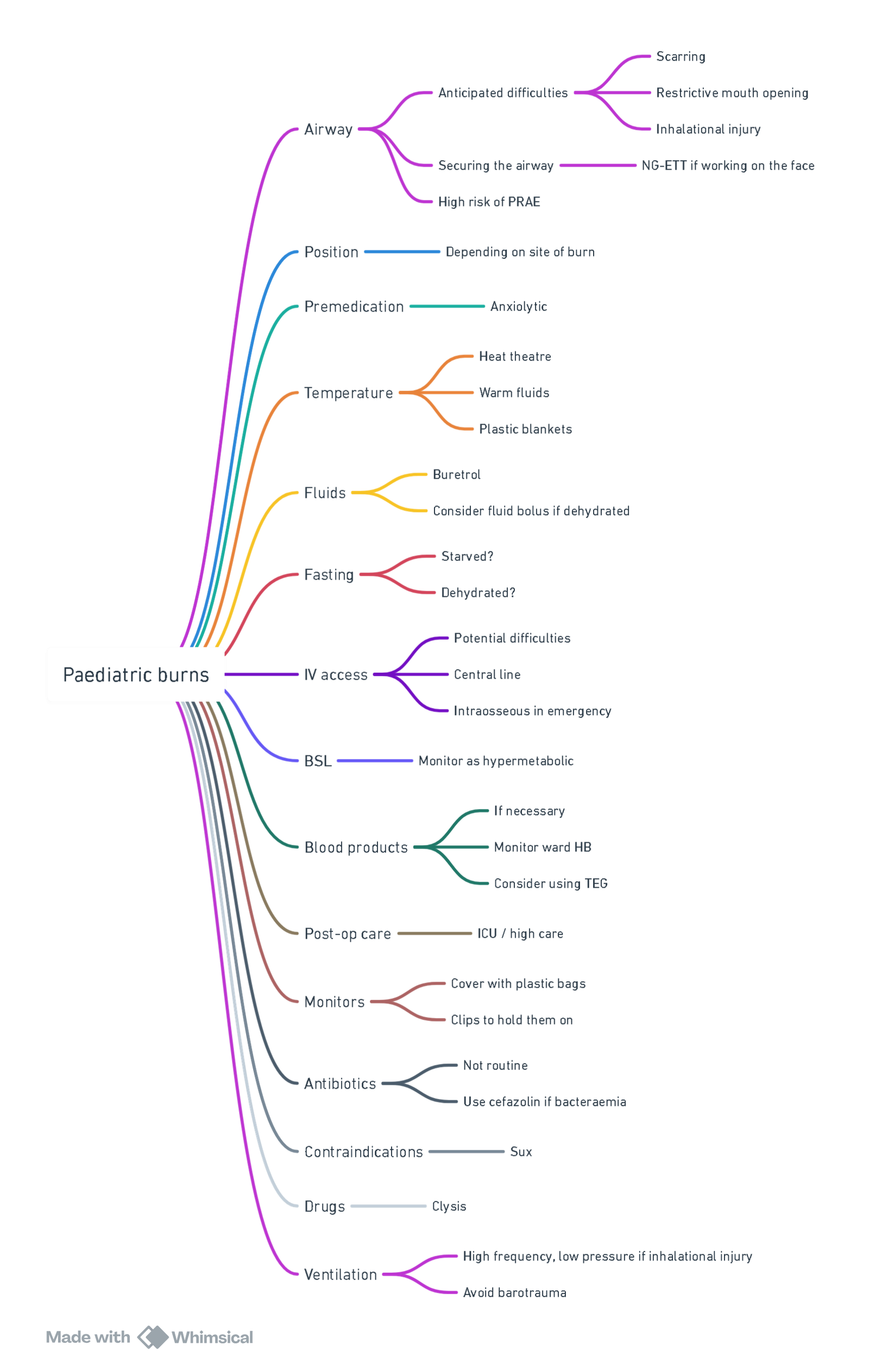

Summary

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Burns in Children: Key Concepts

Introduction

In the treatment of burns in children, a humane, friendly, gentle, and encouraging approach is essential. Burn injuries not only cause immediate physical harm but also result in long-term suffering and scarring. The burns of today lead to future pain and lifelong scars, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive and compassionate care.

Survival Factors

Survival Depends On

- Age of the patient–Younger children, particularly neonates, have a higher mortality risk, despite being more likely to survive.

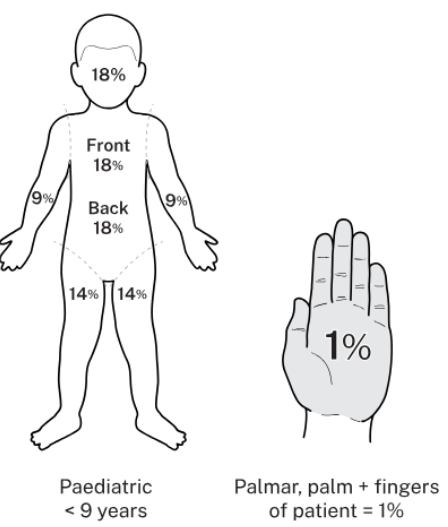

- Site, depth, and percentage of total body surface area (TBSA) burned.

- Presence or absence of inhalational injury–Inhalational injuries significantly increase mortality.

Factors Impacting Survival

- Burn shock and resuscitation–Prompt and adequate fluid resuscitation is critical in preventing burn shock.

- Inhalational injury–Presence of airway burns worsens prognosis.

- Rapidity of wound closure–Early wound closure is crucial to prevent infection and reduce hypermetabolic response.

- Burn hypermetabolism–Burn injuries trigger a hypermetabolic state that requires appropriate nutritional support to manage.

Types of Burns

- Thermal (most common)

- Electrical

- Radiation

- Chemical

Inhalational Injury

Diagnosis of Inhalational Injury

History of the Injury

- Suspect inhalational injury if the patient was trapped in an enclosed space during the burn incident.

Clinical Suspicion

- Burns to the face, neck, eyes, upper trunk, and nose.

- Singed eyebrows, eyelashes, and nose hairs.

- Soot in the sputum.

- Hoarseness, stridor, respiratory distress, and use of accessory muscles for breathing.

- Change in voice and brassy cough.

- Abnormal chest X-ray findings, such as patchy opacification or “white-out” appearance.

- Arterial blood gas showing low PaO2.

- Raised carboxyhaemoglobin levels (indicating carbon monoxide inhalation).

Salient Features of Inhalational Injury

- Stridor, brassy cough, and dysphonia.

- Respiratory distress.

- In children, inhalational injury may be misdiagnosed as croup, tracheomalacia, or tracheobronchitis.

- Symptoms can be delayed up to 48 hours post-injury.

- Endotracheal intubation is required in more than 50% of children with airway burns.

- Endoscopy is performed to assess the severity of injury and manage the airway, especially when upper airway laryngoscopy is inadequate to evaluate damage below the vocal cords.

- Secondary pneumonia occurs in more than 50% of cases.

- High-frequency, low-pressure ventilation is preferred to minimize the risk of barotrauma.

- Increased fluid requirements are necessary to maintain haemodynamic stability.

- Inhalational injury increases mortality by 50%, independent of the TBSA burned.

- Aerosolized heparin may be used to loosen airway casts.

- Prophylactic antibiotics and steroids are not recommended.

Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS)

Toxic shock syndrome should be considered in any burned child who appears more ill than would be expected given the extent of their burns. TSS most commonly occurs in children younger than two years old and typically within two days of a burn injury involving less than 10% TBSA.

Classification of Burns

- Most burns are a combination of superficial and deep layers and are best assessed after 2–3 days.

- The type of pain experienced depends on the depth of the burn:

- Acute nociceptive inflammatory pain for superficial burns.

- Neuropathic pain for deeper burns.

- No pain in areas of full-thickness (deep) burns where nerve endings are destroyed.

Burn Classification

| Depth | History | Aetiology | Sensation | Appearance | Healing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial: Epidermis | Momentary exposure | Sunburn, Momentary hot fluid | Sharp, uniform pain | Blanches red to pink, Oedematous, Soft, flaking, peeling | ± 7 days |

| Partial thickness: Epidermis plus dermis | Exposure of limited duration to lower temperature agents (40–55 °C) | Scalds, Flash burns without contact, Weak chemicals | Dull or hyperactive pain, Sensitivity to air or temperature changes | Mottled and red, Blanches, Red or pink blisters, Oedema, Serous exudate, Thin eschar | 14–21 days |

| Full thickness: No dermis remaining | Long duration of exposure to high temperatures | Immersion, Flame, Electrical, Chemical | Painless to touch and pin prick, May hurt at deep pressure | No blanching, Pale white or tan, Charred, hard, dry and leathery, Hair is absent, Thick eschar | Granulates and requires grafting |

| Underlying structures | Prolonged duration of exposure to extreme heat | Electrical, Flame, Chemical | Usually painless | Charred, Skeletonised | Requires extensive debridement |

Physiological Changes in Burns

| Stage | Airway | Breathing and Pulmonary | Circulation | Disability | Drugs | Endocrine | Electrolyte Imbalance | Fluids | Glucose | Gastrointestinal Tract | Haematological | Hepatic | Itching | Kidneys | Pain | Psychological | Skin | Sepsis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early or acute (24-48 hours) | Upper: Obstruction, oedema, hoarseness and stridor. Lower: Smoke inhalation, chemical pneumonitis, wheezing, respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia and pulmonary oedema. | Hypoxia, carbon monoxide poisoning and cyanide toxicity. | Hypovolaemia, decreasing cardiac output, increasing systemic vascular resistance and ischaemic reperfusion injury. | Confusion, cerebral oedema and increasing intracranial pressure. | Suxemethonium: Hyperkalaemia after ± 1-2 hours after injury. Avoid use after 12 hours after injury. | Release of stress hormones. Decreasing T3 and T4. | hypocalcaemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, hyponatraemia and hypernatremia. | ‘Fluid creep’: Oedema after over-resuscitation*. Oedema is directly proportional to fluid administration. Abdominal compartment syndrome. | Insulin resistance. | Gastric stasis, ulcerations and small bowel ischaemia. Endotoxaemia. ‘Use the gut or lose it’ (ileus and haemodynamic shock are contraindications). Ischaemic bowel syndrome. Abdominal compartment syndrome. | Initial haemoconcentration, then haemodilution from resuscitation, blood loss and erythrocyte damage from heat. | Hepatic injury: Decreasing alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase | Uncommon early. | Decreasing glomerular filtration rate and myoglobinuria. Maintain urine output 0.5–1 mL/kg/hour. | Acute severe pain. | Post-traumatic stress disorder. | Infection, fluid and heat loss. | Major cause of morbidity. |

| Late (> 48 hours) | Ongoing acute responses. Scarring of the face and airway: Limited mouth opening and chin extension. Lung fibrosis and restrictive lung disease. | Increasing cardiac output, hypertension and tachycardia. | Burn encephalopathy: Seizures, hallucinations, personality disorders, coma and delirium. Causes: Hypoxia, sepsis, hyponatraemia and cortical vein thrombosis. | Suxemethonium: Hyperkalaemia. Non-depolarising muscle relaxants: Resistance to effects. Opioids: Tolerance. | May require blood products. Monitor clinically and biochemically. | Acalculous cholecystitis. Bowel ischaemia, endotoxaemia and abdominal compartment syndrome. | Hypercoagulable state. Disseminated intravascular coagulation with sepsis. | Increasing albumin and transferrin. Increasing acute phase proteins. | Caused by drugs (e.g. morphine) or nerve and tissue regeneration. | Increasing glomerular filtration rate and tubular dysfunction. | Chronic pain, neuropathic pain and phantom limb pain. | Depression, suicidal tendencies and post-traumatic disorders. | Loss from graft failure contributes to ongoing infection, and heat and fluid loss. |

Burn injuries cause significant physiological changes in various systems of the body, classified into early (first 24–48 hours) and late (>48 hours) stages.

Airways

- Upper airway:

- Early: Obstruction, oedema, and stridor due to thermal damage.

- Late: Scarring of the face, leading to limited facial movement and restricted mouth opening; potential for tracheal stenosis.

- Lower airway:

- Early: Smoke inhalation leading to wheezing, respiratory distress, and pulmonary oedema.

- Late: Potential scarring and airway damage from prolonged exposure and inflammation.

Pulmonary System

-

Early:

- Hypoxia: Due to airway injury or inhalation of toxic gases.

- Carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning: Requires prompt diagnosis and treatment.

-

Late:

- Circumferential chest wall restriction: Burns involving the chest can limit respiratory expansion.

- Infection: Pulmonary infections are common and may lead to pneumonia.

- Restrictive lung disease: Progressive fibrosis causes restrictive lung patterns, reducing lung compliance.

Circulation

- Early:

- Hypovolaemia: Fluid loss from burn surfaces results in significant volume depletion.

- Decreased cardiac output (CO): The initial response to hypovolaemia.

- Increased systemic vascular resistance (SVR): As part of the body’s compensatory mechanisms.

- Ischaemia-reperfusion injury: Due to fluid shifts and tissue damage.

- Late:

- Increased cardiac output (CO): As the hypermetabolic state progresses.

- Hypertension and tachycardia: Often associated with the late hyperdynamic circulatory state.

Neurology

- Confusion, cerebral oedema, and raised intracranial pressure (ICP) due to metabolic derangements and hypoxia.

- Burns encephalopathy: Characterized by confusion, seizures, delirium, hallucinations, and coma. Causes include hypoxia, sepsis, cortical vein thrombosis, and hyponatremia.

Pharmacological Considerations

- Suxamethonium contraindicated after 12 hours post-burn due to risk of hyperkalaemia.

- Late:

- Resistance to non-depolarizing muscle relaxants (NDMR) due to upregulation of acetylcholine receptors.

- Opioid tolerance: Results from prolonged opioid use during burn management.

Endocrine System

- Early: Reduction in thyroid hormones T3 and T4.

- Late: Hypermetabolic response that lasts up to 1 year, characterized by:

- Increased basal metabolic rate.

- Elevated temperature and catabolism.

Electrolytes

- All electrolytes are affected, with a tendency towards hypo-electrolyte states. Sodium levels can fluctuate between hypo and hypernatremia depending on fluid management.

Glucose Metabolism

- Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia are common due to stress responses and hypermetabolic state.

Gastrointestinal System

- Stasis of the gut, risk of ulceration, and ischaemia.

- Abdominal compartment syndrome may develop due to increased intra-abdominal pressure.

Haematological System

- Hypercoagulable state: Increased risk of thromboembolism.

- Thrombocytopenia: Decreased platelet count may occur due to consumption and sepsis.

Kidneys

-

Early:

- Decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) due to hypoperfusion and myoglobinuria (especially in extensive muscle damage).

- Renal injury caused by hypoperfusion, inflammatory mediators, and release of proteins into plasma.

-

Late:

- Increased GFR and tubular dysfunction in response to fluid resuscitation.

- Late-stage renal injury often results from sepsis or nephrotoxic medications.

Sepsis Consideration

- Sepsis is a significant cause of morbidity in burned patients. Suspect toxic shock syndrome (TSS) if the clinical presentation does not correlate with the extent of the burn area.

Peri-operative Management of Burns in Children

Pre Operative

Resuscitation (RESUS)

The aim of resuscitation is to balance over-resuscitation (which may cause pulmonary oedema) and under-resuscitation (leading to hypoperfusion and organ damage). The goal is to maintain organ perfusion during the shock state and restore intravascular volume. Key endpoints for resuscitation include:

- Urine output: 1–2 mL/kg/hour.

- Mean arterial pressure (MAP): > 65 mmHg.

- Acid-base status: Monitor via arterial blood gases (ABG) to detect metabolic acidosis.

- Serum lactate: Levels > 2 mmol/L may indicate inadequate perfusion.

- Cap refil <3 seconds

Fluid Therapy in Burns Resus

Fluid resuscitation in paediatric burn patients is critical for stabilizing hemodynamics and ensuring adequate tissue perfusion. The approach varies based on the total body surface area (TBSA) affected and the child’s weight.

Indications for Fluid Resuscitation:

- Initiate intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation for children with burns covering ≥10% TBSA

Fluid Calculation:

The Modified Parkland Formula is commonly used to estimate fluid requirements

-

Resuscitation Fluid: Administer 3 mL/kg/%TBSA of a crystalloid solution (e.g., Hartmann’s Solution or Lactated Ringer’s) over the first 24 hours post-injury. Distribute this volume as follows:

- 50% in the first 8 hours

- The remaining 50% over the subsequent 16 hours

Note: The timing starts from the moment of the burn injury, not hospital admission.

-

Maintenance Fluid: In addition to resuscitation fluids, provide maintenance fluids to meet basal metabolic needs. A typical regimen includes sodium chloride 0.9% with glucose 5%, with the rate calculated based on the child’s weight:

- 100 mL/kg/day for the first 10 kg

- 50 mL/kg/day for the next 10 kg

- 20 mL/kg/day for each kilogram over 20 kg

-

or use 4-2-1 (hourly rate)

Adjust maintenance fluids based on oral intake and ongoing assessments.

Monitoring and Adjustments:

- Urine Output: Insert a urinary catheter to monitor urine output, aiming for:

- 1 mL/kg/hour for children weighing less than 30 kg

- 0.5 mL/kg/hour for those over 30 kg

Adjust fluid rates based on urine output and clinical assessment

- Clinical Parameters: Regularly assess heart rate, blood pressure, capillary refill, and mental status. Monitor for signs of both under-resuscitation (e.g., poor perfusion) and over-resuscitation (e.g., edema).

Special Considerations:

- Delayed Presentation: If there’s a delay between the burn injury and initiation of resuscitation, adjust the fluid administration rate accordingly to compensate for the elapsed time.

- Additional Injuries: Patients with inhalation injuries, electrical burns, or associated trauma may require increased fluid volumes. Consult with a specialist team in such cases.

Nil Per Os (NPO)

- Clear fluids: Allowed up to two hours before surgery.

- Nasogastric tube (NGT) feeds: Follow general NPO guidelines, stopping at least 6 hours before surgery.

- Nasojejunal tube (NJT) feeds: Should be individualized, considering the patient’s needs and the timing of surgery.

Anxiety Management

Anxiety tends to increase with repeated visits to the operating theatre, making psychological preparation crucial:

- EMLA™ cream (lidocaine and prilocaine) should be considered for pain relief during procedures.

- Medical play: Child-friendly explanations of what will happen during surgery can reduce anxiety at induction.

- Consider midazolam (0.5 mg/kg orally) for preoperative anxiolysis in extremely anxious children, particularly those older than six months.

Booking the Case

- Patient demographics: Ensure the name, folder number, age, weight, consent, and starting haemoglobin (Hb) level are recorded.

- Surgical factors: Include the percentage of TBSA involved (areas for debridement and donor sites), and the specific site for operation.

- Order of patients: The youngest patients should be scheduled first, with septic patients at the end of the list to minimize the risk of cross-contamination.

- Blood requirements: If blood transfusion is anticipated based on the patient’s Hb and extent of surgery, ensure cross-matching is done. For operations involving >30% TBSA (debridement and donor sites), ensure an appropriate blood volume is available (typically based on estimated blood volume: 80 mL/kg in children).

Blood-sparing techniques may reduce transfusion needs:

- Clysis (subcutaneous infiltration of fluid with adrenaline and local anesthetic).

- Topical adrenaline swabs.

- Fast surgical techniques.

- Use of electrocautery.

Preoperative History

The AMPLE mnemonic is used to gather essential preoperative history:

- Allergies.

- Medications: Current medications, especially those affecting coagulation, analgesia, and any prior anesthesia reactions.

- Pre-existing illnesses: Chronic illnesses such as asthma, diabetes, or epilepsy.

- Last meal: Time of the last intake of food or fluids.

- Events leading to the burn: Mechanism of injury, inhalation exposure, and any associated trauma.

Examination

- Airway: Assess for contractures around the neck or face that may complicate intubation.

- Breathing: Evaluate for respiratory distress, especially in patients with suspected inhalational injury, which increases mortality by 20%. Burns to the chest may cause chest splinting from tight dressings or circumferential burns. Pneumonia independently increases mortality by 40%, and when combined with inhalational injury, the risk of death increases by 60%.

- Circulation: Assess capillary refill and the adequacy of IV access.

- Disability: Use the AVPU scale to assess consciousness: Alert, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, Unresponsive.

- Fluids: Evaluate fluid balance–what, how much, and by which route the fluids are being administered.

- Glucose: Monitor glucose levels to manage stress hyperglycaemia.

Investigations

- Recent haemoglobin (Hb) level: To assess for anaemia and the potential need for transfusion.

- Platelet count (PTL) and coagulation profile: Check for any coagulopathies that could increase intraoperative bleeding risk.

- Arterial blood gas (ABG): If sepsis is suspected, to assess acid-base balance, oxygenation, and ventilation status.

- Chest X-ray (CXR): Only indicated if respiratory disease or inhalational injury is suspected.

Premedication

Premedication should address pain, anxiety, amnesia, and sedation:

-

Analgesia:

- Paracetamol: 15 mg/kg orally or rectally.

- Morphine: 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV for pain relief.

- Tilidine hydrochloride (Valoron™): 1 mg/kg orally.

- Clonidine: 2–5 mcg/kg orally or IV.

- Ketamine: 0.5 mg/kg orally or intranasally for analgesia and sedation.

- Gabapentin: 10–20 mg/kg orally for neuropathic pain.

-

Sedation:

- Trimeprazine (Vallergan™): 1–2 mg/kg orally.

- Hydroxyzine: 0.5–1 mg/kg orally.

- Promethazine: 0.5–1 mg/kg orally.

- Droperidol: 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV.

-

Anxiolysis:

- Midazolam: 0.5 mg/kg orally (maximum 20 mg).

- Lorazepam: 0.05 mg/kg orally or IV.

- Hydroxyzine: 0.5–1 mg/kg orally.

- Diazepam: 0.1–0.3 mg/kg IV or rectally.

-

Amnesia:

- Benzodiazepines (e.g., midazolam or lorazepam).

- Ketamine: 1–2 mg/kg IV or 6–10 mg/kg IM.

- Droperidol: 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV.

Intraoperative Management

Theatre Preparation

- Airway management: Be prepared with all airway devices (ETT, LMA, etc.).

- IV access: Insert large-bore cannulas for fluid and blood administration.

- Temperature control: Keep the theatre temperature above 28°C to prevent hypothermia. Warm IV fluids and use warming blankets.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not routinely administered but are used for patients with confirmed bacteraemia. For burn debridement:

- Cefazolin: 50 mg/kg IV every 8 hours.

- For penicillin-allergic patients:

- Clindamycin: 20 mg/kg IV every 6–8 hours.

Anaesthesia

- General anaesthesia: Can be administered either intravenously or via inhalation. Multimodal analgesia is commonly used.

Ketamine Infusion Protocol

Infusion Rate

- Standard range: 4–12 mg/kg/hour

- Preparation:

- Concentration: 200 mg in 50 mL normal saline (4 mg/mL)

- Administration: Run at the child’s body weight in mL/hour to deliver 4 mg/kg/hour

Pharmacokinetic-Based Infusion Adjustments

- Following a 2 mg/kg loading dose, the infusion rate should decrease over time to maintain a target concentration of 3 mg/L.

- Stepwise infusion reduction:

- Initial rate: 11 mg/kg/hour

- After 20 minutes: Reduce to 7 mg/kg/hour

- After another 20 minutes: Reduce to 5 mg/kg/hour

- After another 20 minutes: Reduce to 4 mg/kg/hour

Simplified Protocol (Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital)

- Initial rate: 12 mg/kg/hour

- After 20 minutes: Reduce to 8 mg/kg/hour

- After another 20 minutes: Reduce to 4 mg/kg/hour

Practical Calculation at 4 mg/mL Concentration

- 12 mg/kg/hour: Administer at 3 × body weight (mL/hour)

- 8 mg/kg/hour: Administer at 2 × body weight (mL/hour)

- 4 mg/kg/hour: Administer at 1 × body weight (mL/hour)

Midazolam

- Bolus: 0.1–0.2 mg/kg IV.

- Infusion: 0.1–0.2 mg/kg/hour. Combine midazolam with ketamine in a single syringe for continuous infusion.

Additional Anaesthetic Agents

- Nitrous oxide and oxygen via nasal cannula (2–3 L/min) can supplement analgesia, particularly during ketamine TIVA.

Airway Control

- Nasal cannula with capnography: Ideal for ketamine infusion without airway instrumentation.

- Laryngeal mask airway (LMA): Useful for burns to the lower body. Perform laryngoscopy to clear secretions before placement.

- Endotracheal tube (ETT): For secure airway control, especially for facial or neck burns.

Procedure for Securing the Airway

- Intubation: Perform oral intubation with an ETT.

- NGT Placement: Insert a nasogastric tube (NGT) through one nostril until it reaches the nasopharynx.

- Retrieval: Using Magill forceps, grasp the tip of the NGT and pull it out through the mouth, creating a loop around the hard palate.

- Tensioning: Pull both ends of the NGT taut to remove slack.

- Alignment and Securement: Align both ends of the NGT with the ETT and secure them together firmly using a cable tie.

- Avoiding Tube Crimping:

- Tie firmly but not excessively tight to prevent crimping of the ETT, which could reduce the internal diameter.

- Cut the ETT to the desired length.

- Replace the connector and use it as a stent to maintain lumen patency at the cable tie.

Blood Loss Management

- Adrenaline: Topical application (3 mg in 1L normal saline) to control bleeding.

- Clysis: Local infiltration with bupivacaine (100 mg in 1L Ringer’s lactate) and adrenaline (2 mg).

- Bipolar diathermy: Helps minimize bleeding during surgery.

Fluid Management

For large surgeries:

- Preload with 10–20 mL/kg of crystalloid (Ringer’s lactate or Plasmalyte® B).

- Ensure cross-matched blood is available. Monitor blood loss and haemoglobin levels intraoperatively.

Monitoring

- Temperature control: Ensure normothermia using warm fluids, blankets, overhead heaters, and warm air devices.

- ECG: Use surgical staples or crocodile clips for better adhesion.

- Oximetry: Place the pulse oximeter on the same limb as the IV, and cover with a waterproof bag.

- Invasive monitoring: Secure central lines and communicate with the surgical team about their placement.

Indications for GA and Dressing Changes

- Large burns (>20% TBSA).

- Burns to sensitive areas (face, hands, feet, perineum).

- Patients with cognitive impairments or PTSD.

- Extensive scar manipulation or dressing removal that causes significant pain.

Postoperative Management

- Handover: Clear communication between theatre and ward staff is essential.

- Pain control: Effective analgesia is crucial postoperatively.

- Fluid balance: Ongoing losses from operative sites require careful monitoring.

- Temperature: Actively warm the child postoperatively to prevent hypothermia.

- Feeding: Reintroduce feeding and fluids early. Manage nausea and vomiting aggressively.

Pain Management in Paediatric Burn Patients

Burn injuries involve complex pain mechanisms, including nerve damage and inflammatory pain, which fluctuate during the healing process. Adequate pain management in the initial stages of burn injury can help prevent the development of chronic pain and significantly improve the quality of life for burn survivors.

Types of Pain in Burn Survivors

- Acute pain: Immediate pain from the burn injury itself, exacerbated by medical procedures such as dressing changes and debridement.

- Chronic pain: Long-term pain that persists even after the wound has healed, often involving elements of neuropathic pain.

- Neuropathic pain: Resulting from nerve damage, presenting as burning, tingling, or shooting pain.

Challenges in Pain Management

- Inadequate emotional support and reintegration back into society, which can contribute to the persistence of pain.

- Misconceptions about drug side effects and fear of addiction, leading to underutilization of appropriate pain management therapies.

- A lack of understanding that effective pain control is not only ethical but is scientifically backed, contributing to better patient outcomes and recovery.

- Resource limitations and poor concern from caregivers, leading to inadequate pain management.

- Itching (pruritus) is a significant component of the pain experience and often overlooked in management.

Management Strategies

Nonpharmacological Strategies

- Distraction techniques: Child-friendly interventions such as play therapy, music therapy, and art therapy can help distract children from pain and improve their psychological well-being.

- Psychotherapy: Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and counseling can help reduce anxiety and fear associated with pain.

- Child life therapists: These professionals provide age-appropriate explanations and emotional support to children during painful procedures.

Pharmacotherapy

1. Simple Analgesics

- Paracetamol: A foundational analgesic for managing mild to moderate pain in paediatric burns.

- Dose: 15 mg/kg/dose every 4–6 hours (maximum 75 mg/kg/day).

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Effective for controlling inflammation and reducing mild to moderate pain.

- Ibuprofen: 5–10 mg/kg every 6–8 hours (maximum 40 mg/kg/day).

- NSAIDs should be used with caution in patients with renal impairment or those at risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

2. Opioids

- Morphine: Mainstay for moderate to severe burn pain, especially in acute settings.

- Dose: 0.05–0.1 mg/kg IV every 2–4 hours or 0.2–0.5 mg/kg orally every 4–6 hours.

- Fentanyl: Potent opioid for severe pain, often used in procedural sedation.

- Dose: 1–2 mcg/kg IV every 30–60 minutes.

- Sufentanil: Ultra-potent opioid, used in severe cases or intraoperatively.

- Dose: 0.2–0.6 mcg/kg IV.

- Tilidine hydrochloride (Valoron™): Another option for moderate to severe pain.

- Dose: 1 mg/kg orally.

- Codeine: Weak opioid used for mild to moderate pain but limited due to variability in metabolism.

- Dose: 0.5–1 mg/kg orally every 4–6 hours.

3. Adjuncts

- Clonidine: Alpha-2 agonist with analgesic and sedative properties, often used as an adjunct to opioids.

- Dose: 2–5 mcg/kg orally or IV every 8–12 hours.

- Gabapentin: Particularly useful for neuropathic pain and pruritus.

- Dose: 10–20 mg/kg/day divided into two or three doses.

- Gabapentin is effective in reducing chronic pain and itching in paediatric burn patients.

- Antidepressants: Especially tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) like amitriptyline for chronic or neuropathic pain management.

- Amitriptyline: 0.1–0.5 mg/kg/day, given at night.

4. Anaesthetics

- Ketamine: Used for procedural sedation and pain relief.

- Induction: 1–2 mg/kg IV or 6–10 mg/kg IM.

- Infusion: 4–12 mg/kg/hour.

- Entonox™ (Nitrous oxide and oxygen): Inhaled analgesic for quick pain relief during minor procedures.

- Local anaesthetics: Such as lidocaine or bupivacaine can be used for regional or local anaesthesia in donor or debridement sites.

Chronic Pain Management

Chronic pain in burn patients often includes elements of neuropathic pain, anxiety, and fear. It is critical to address these components early and aggressively.

- Neuropathic pain: Gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) are first-line agents.

- Anxiety and fear: Psychological support, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), is vital to reduce the emotional burden of chronic pain.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Common in burn survivors, requiring a multidisciplinary approach with mental health professionals.

To prevent withdrawal symptoms, analgesic and anxiolytic medications used during burn care should be weaned gradually, rather than abruptly discontinued. This strategy is particularly important for patients who have received long-term opioid therapy.

Links

References:

- Thomas, J. and Bester, K. (2014). Paediatric burns anaesthesia: the things that make a difference. Southern African Journal of Anaesthesia and Analgesia, 20(5), 190-196. https://doi.org/10.1080/22201181.2014.979630

- Thomas JM, Rode H. A practical guide to paediatric burns. Cape Town: SAMA Health and Publishing Group; 2006.

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

Paediatric burns

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “50848590-ef8b-462e-9351-dda74f69ddc9”