- Arterial Cannulation

- Indications

- Contraindications

- Site Selection

- Technique

- Maintenance & Infection Prevention

- Complications and Mitigation

- Arterial Pressure Waveform Interpretation

- Special Situations

- Normal ABG on Room Air

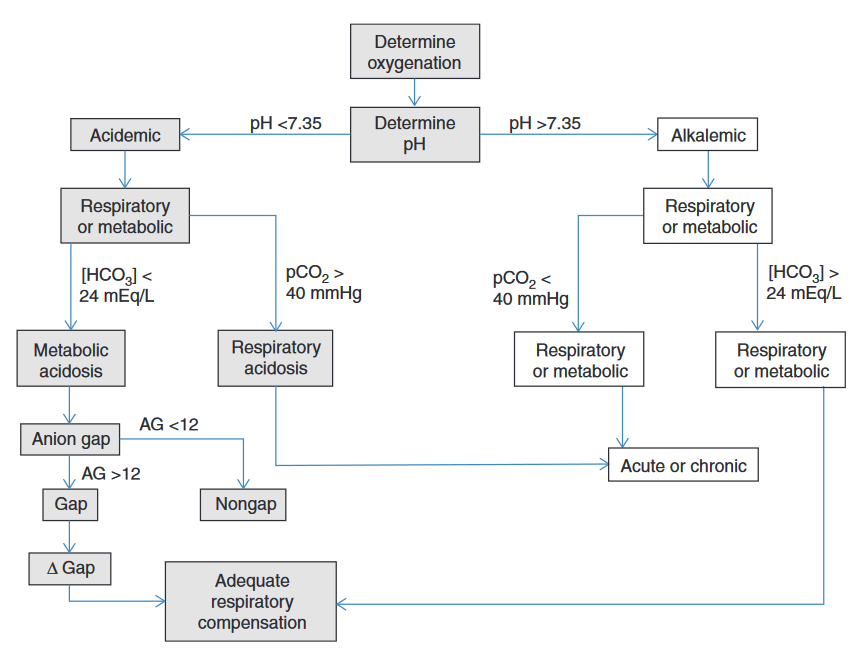

- Steps to Interpret Acid-Base Disturbances

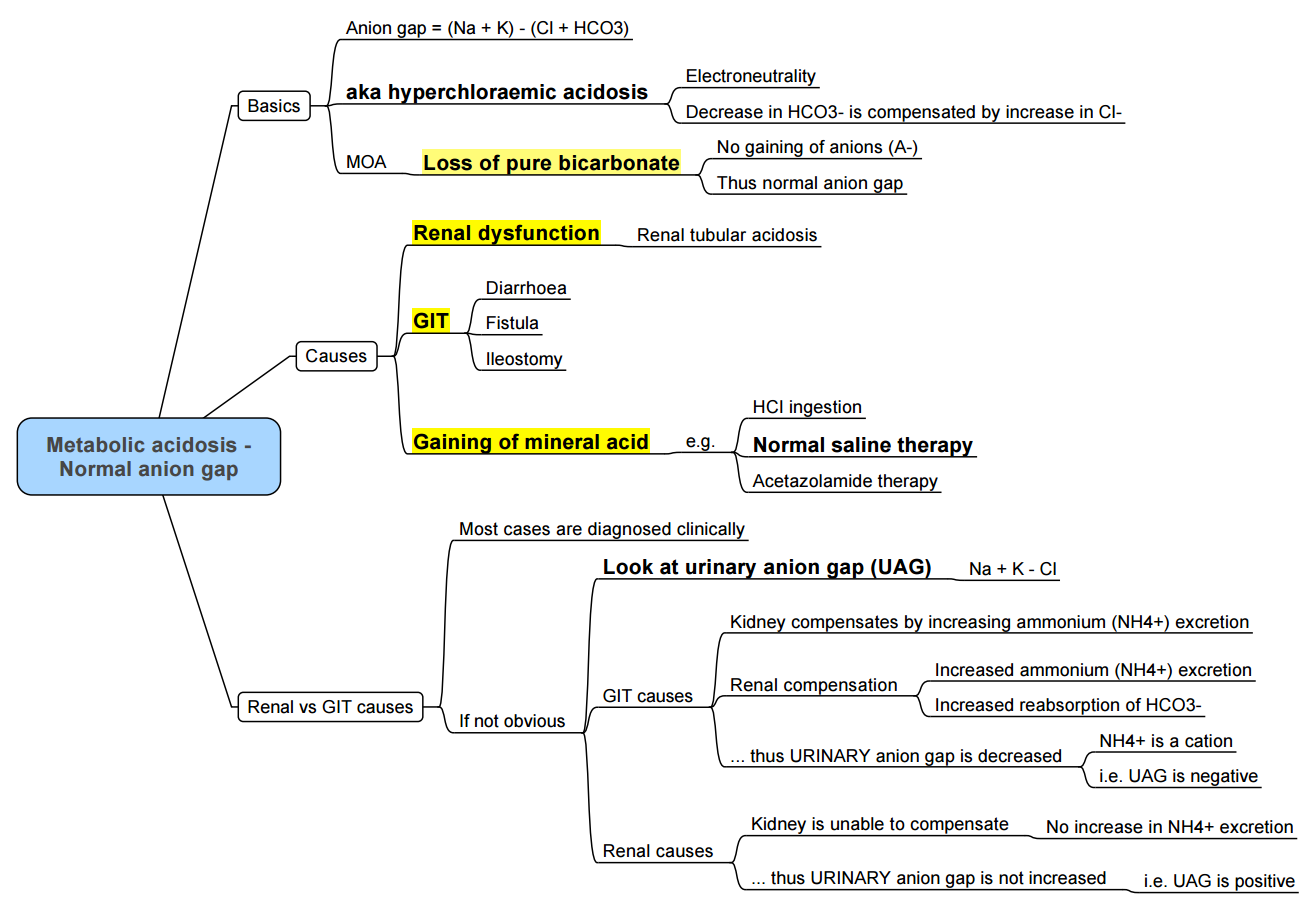

- Metabolic Acidosis Considerations

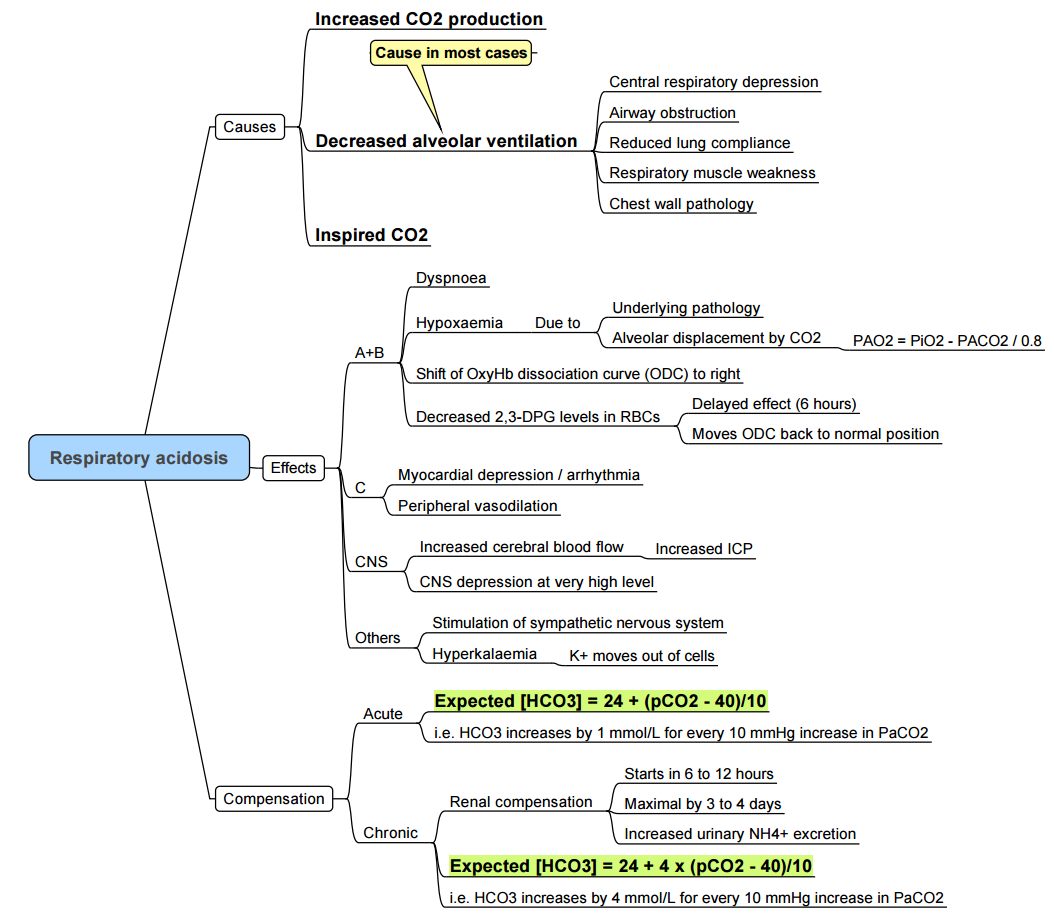

- Respiratory Acidosis Considerations

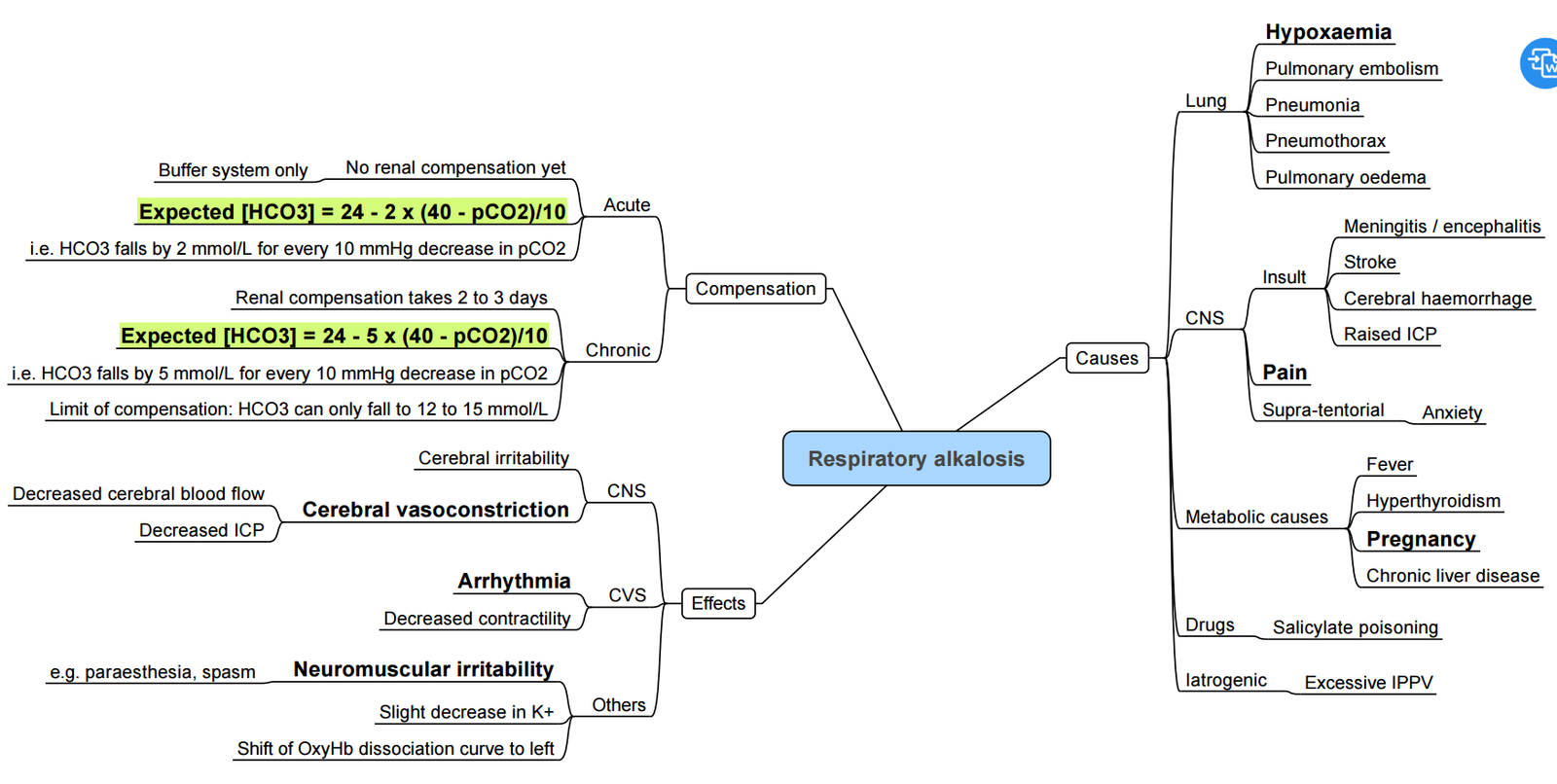

- Respiratory Alkalosis

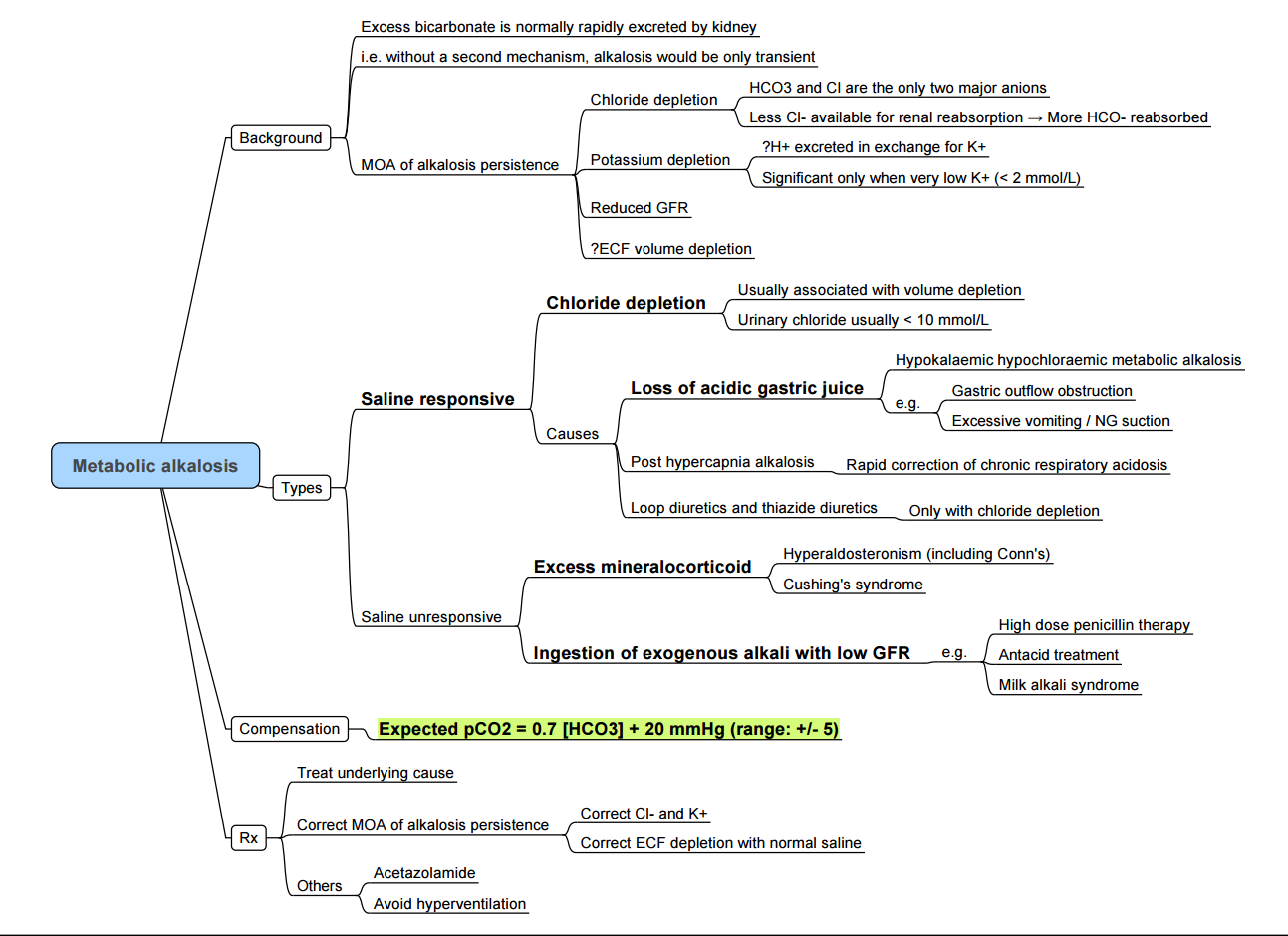

- Metabolic Alkalosis

- Links

{}

Arterial Cannulation

Indications

- Beat-to-beat arterial blood pressure and mean arterial pressure (MAP) monitoring during major surgery, haemodynamic instability, extracorporeal circuits (e.g. ECMO, IABP) and thrombolysis or hypertensive emergencies.

- Frequent arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis or lactate trending.

- Continuous sampling for laboratory investigation when venous access is unreliable.

- Advanced haemodynamic calculations (pulse-contour cardiac output, stroke-volume or pulse-pressure variation).

- Neuro-anaesthesia, trauma or stroke cases in which tight cerebral perfusion pressure control is required.

- Major burns, obstetric crises (e.g. massive haemorrhage) and paediatric cardiac surgery where invasive pressures guide resuscitation.

Contraindications

Absolute

- Absent distal pulse or proven inadequate collateral circulation (Doppler, plethysmography).

- Local infection, burn or traumatic disruption at the proposed site.

- Prior radial artery harvest/prosthetic graft in the limb.

- Critical limb ischaemia or unreconstructable peripheral vascular disease.

Relative

- Coagulopathy (platelets < 50 × 10⁹ L⁻¹ or INR > 2) or therapeutic anticoagulation.

- Raynaud phenomenon, Buerger disease, severe vasospasm.

- ipsilateral arteriovenous fistula/lymphoedema/axillary node dissection.

- High-dose vasopressor infusion (risk of digital ischaemia).

- Sugical field proximity or planned limb positioning incompatible with line security.

Site Selection

| Site | Advantages | Disadvantages | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial | Superficial, low infection rate, palmar collateral flow | Small calibre in shock/children | Preferred; ultrasound first-pass success >90 % |

| Ulnar | Preservation of radial grafts | Deeper, smaller, proximity to ulnar nerve | Reserve for failed radial |

| Brachial | Large calibre, easy ultrasound view | End artery, median nerve injury risk | Acceptable for ≤48 h with ≤20 G catheter |

| Axillary | Central pressure, mobile limb | Plexus proximity, technical | Useful when femoral contraindicated |

| Femoral | Rapid access in shock/CPR, reliable waveform | Higher bleed/infection if asepsis poor | Ideal in major vasoconstriction or CPB gradients |

| Dorsalis pedis / Posterior tibial | Accessible prone/upper-limb burns | Amplified systolic BP, distal ischaemia | Continuous foot perfusion checks |

Technique

- Ultrasound guidance (short-axis out-of-plane or long-axis in-plane) is recommended; meta-analysis shows higher first-pass success, fewer attempts and haematomata than palpation.

- Direct over-the-needle, Seldinger or modified Seldinger techniques are acceptable; choose smallest catheter that provides reliable waveform (20–22 G adults, 22–24 G paediatrics).

- Zero transducer at the phlebostatic axis (4th intercostal, mid-axillary); re-zero after patient repositioning >15 °.

- Fast-flush test daily to confirm adequate natural frequency (>10 Hz) and optimal damping (1–2 oscillations).

Maintenance & Infection Prevention

- Pressurised (300 mmHg) 0.9 % saline at 2–3 mL h⁻¹; routine heparinised flush offers no patency benefit and risks thrombocytopenia—avoid unless repeated clotting occurs.

- Chlorhexidine–alcohol skin preparation, maximal sterile-barrier precautions, sterile ultrasound cover and dedicated transducer.

- Transparent dressing with date/time; inspect insertion site at least once per shift.

- Daily line-necessity check—catheter-related bloodstream infection risk rises steeply after day 4–5; remove or resite where feasible.

Complications and Mitigation

| Category | Incidence | Prevention/Management |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical failure / haematoma | 6–28 % | Ultrasound, <3 attempts, compression 5 min |

| Thrombosis / digital ischaemia | 0.1–0.5 % | Small catheter, limb perfusion checks, remove if blanching |

| Catheter-related infection | 0.15 per 1000 catheter-days | Strict asepsis, minimise dwell time |

| Haemorrhage / line disconnection | <1 % | Locking connectors, alarms, securement device |

| Nerve injury (median, radial) | Rare | Use ultrasound to visualise nerve, avoid multiple passes |

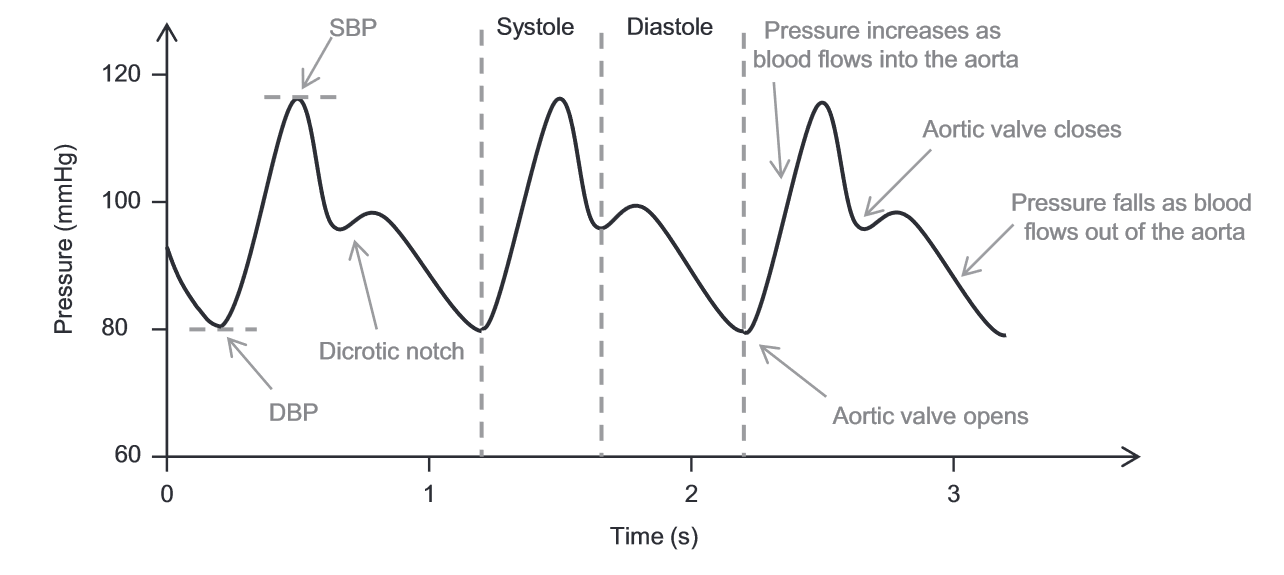

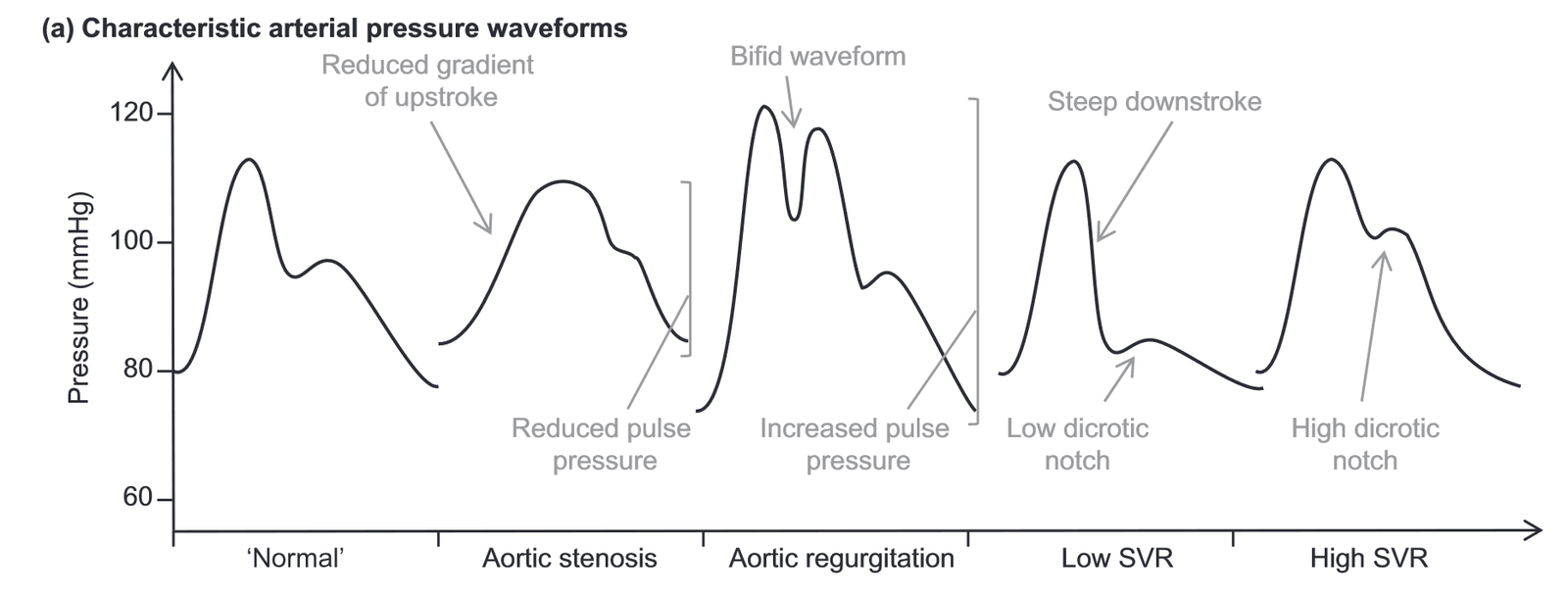

Arterial Pressure Waveform Interpretation

- Components: rapid systolic upstroke → peak systolic → dicrotic notch (aortic valve closure) → diastolic runoff → end-diastolic pressure.

- Peripheral amplification: from aorta to radial the systolic rises (~5–20 mm Hg), diastolic falls; MAP remains constant.

- Dynamic response errors:

- Underdamped–tall, narrow peaks, overshoot SBP, wide pulse pressure.

- Overdamped–blunted upstroke, loss of dicrotic notch, underestimated SBP.

- Troubleshooting: remove air/clots, shorten tubing (<120 cm), ensure 300 mm Hg flush pressure, replace kinked catheter/tubing.

Special Situations

- Paediatrics/neonates: ultrasound guidance markedly improves success; 24 G radial or posterior tibial preferred.

- Cardiac bypass/vasopressor use: dual radial + femoral lines detect radial–central gradient.

- Prone ventilation/major burns: secure limb padding, consider dorsalis pedis.

- South African context: higher prevalence of HIV, diabetes and peripheral vascular disease—ultrasound enhances safety, and resource-adjusted protocols should balance cost with reduction in complications and cannulation time.

Normal ABG on Room Air

- pH: 7.40

- pCO2: 40 mmHg

- HCO3: 24 mEq/L

- Normal O2: > 80 mmHg

- Normal Anion Gap (AG): 12 ± 2

Steps to Interpret Acid-Base Disturbances

1. Adequate Oxygenation?

- Normal O2: > 80 mmHg

- Possible Hypoxemia: Consider if pO2 is less than expected.

2. Define the Acid-Base Disturbance

- pH < 7.35: Acidemia

- Metabolic Acidosis: Gain of acid or loss of HCO3⁻

- Respiratory Acidosis: Hypoventilation, increased pCO2

- pH > 7.45: Alkalemia

- Metabolic Alkalosis: Gain of HCO3⁻ or loss of acid

- Respiratory Alkalosis: Hyperventilation, decreased pCO2

3. Identify the Primary Process

-

Metabolic Acidosis:

- Acute: HCO3⁻ < 24 mEq/L with corresponding pCO2 compensation

- Chronic: Same pattern but over longer duration

-

Respiratory Acidosis:

- Acute: Elevated pCO2 with minimal change in HCO3⁻

- Chronic: Elevated pCO2 with compensatory increase in HCO3⁻

-

Metabolic Alkalosis:

- Acute: HCO3⁻ > 24 mEq/L with compensatory increase in pCO2

- Chronic: Same pattern but over longer duration

-

Respiratory Alkalosis:

- Acute: Decreased pCO2 with minimal change in HCO3⁻

- Chronic: Decreased pCO2 with compensatory decrease in HCO3⁻

4. Compensatory Mechanisms

A. Metabolic Disorders

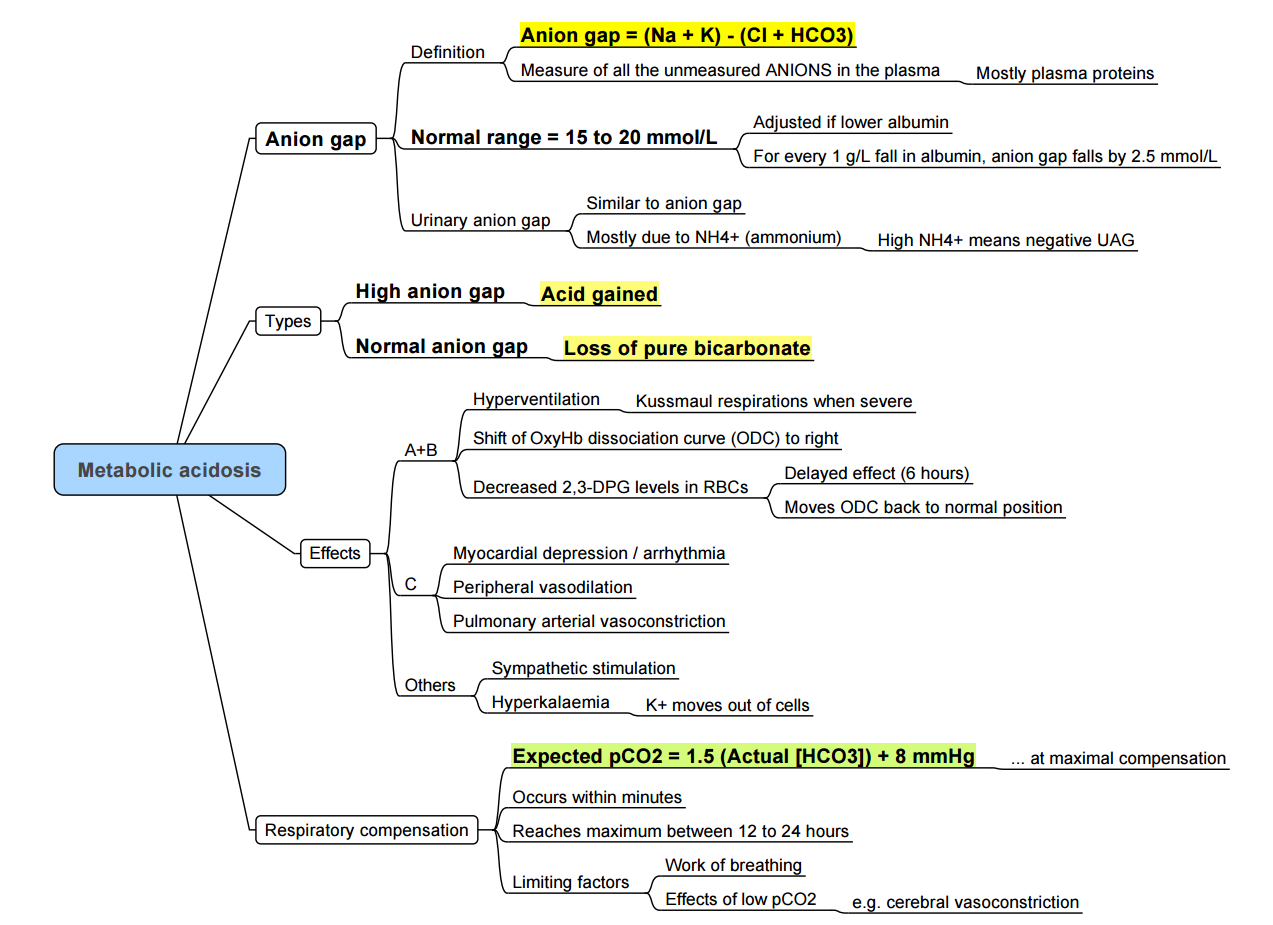

- Metabolic Acidosis (Winter’s formula)

- pCO2 expected=(1.5×[HCO3−])+8 ± 2(mmHg)

- Metabolic Alkalosis

- pCO2 expected=(0.7×[HCO3−])+20(mmHg)

B. Respiratory Disorders

ΔPCO₂ = (measured PCO₂ – 40 mmHg).

- Respiratory Acidosis

- Acute:

Δ[HCO3−]=0.1×ΔpCO2⟹

(HCO3−)exp=24+0.1×(pCO2−40) - Chronic:

Δ[HCO3−]=0.35×ΔpCO2⟹

(HCO3−)exp=24+0.35×(pCO2−40)

- Acute:

- Respiratory Alkalosis

- Acute

Δ[HCO3−]=0.2×(40−pCO2)⟹

(HCO3−)exp=24−0.2×(40−pCO2) - Chronic:

Δ[HCO3−]=0.35×(40−pCO2)⟹

(HCO3−)exp=24−0.35×(40−pCO2)

- Acute

5. Calculate Anion Gap (AG)

- AG: Na⁺ – (Cl⁻ + HCO3⁻)

- Normal AG: 12 ± 2

- High AG: Presence of unmeasured anions

6. Normal AG Metabolic Acidosis (NAGMA)

- Causes:

- GI Losses of HCO3⁻ (Diarrhea)

- Renal Tubular Acidosis (RTA)

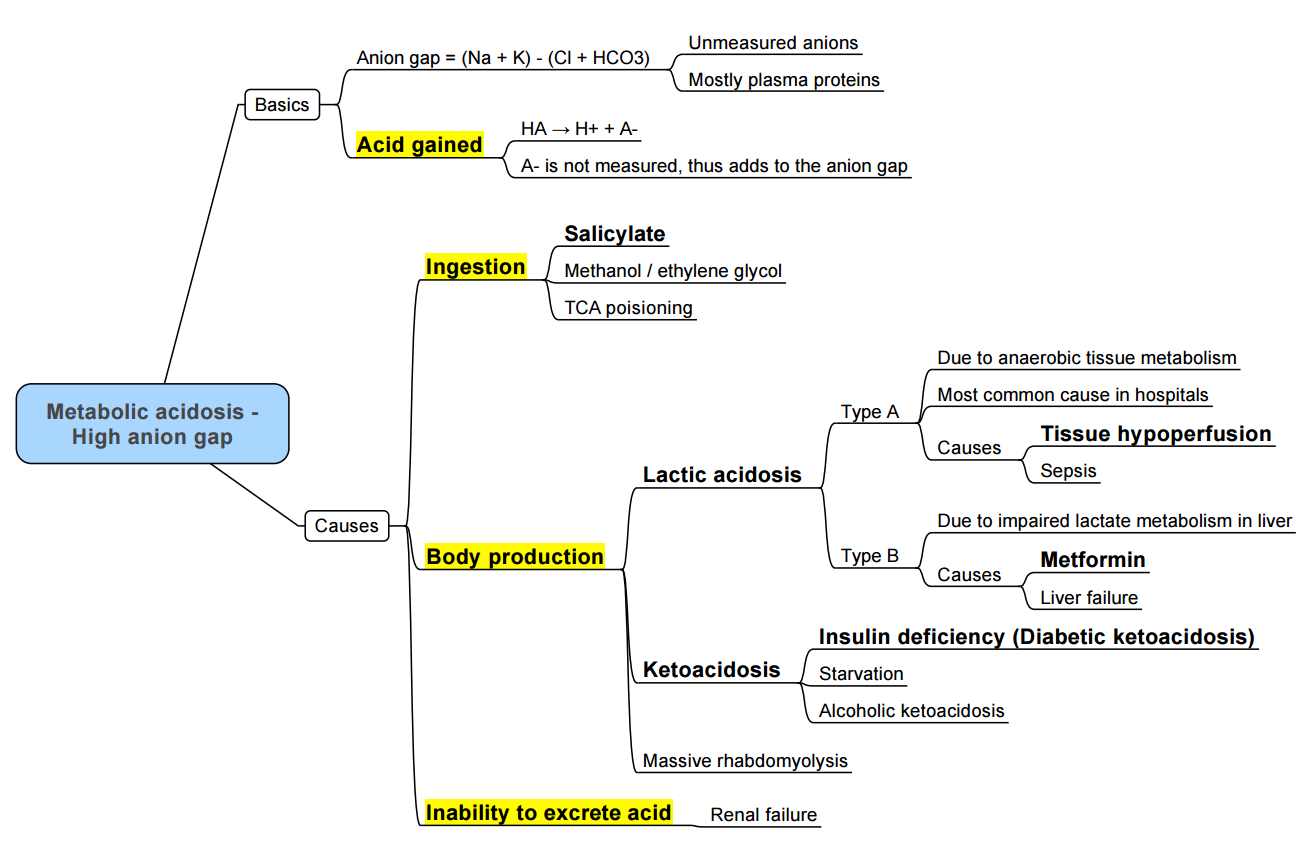

7. High AG Metabolic Acidosis (HAGMA)

- Causes: Accumulation of acids like lactate or ketones, renal failure, toxins.

8. Compensation and Mixed Disorders

- Winter’s Formula for Metabolic Acidosis: Expected pCO2 = 1.5 × (HCO3⁻) + 8 ± 2

- Delta-Delta (Δ/Δ) Ratio: Used to identify mixed disorders

Metabolic Acidosis Considerations

Winter’s Formula

PCO2=(1.5×HCO3)+8

- Interpretation:

- If measured PCO2 > calculated PCO2: Concurrent respiratory acidosis is present.

- If measured PCO2 < calculated PCO2: Concurrent respiratory alkalosis is present.

Delta Gap (Δ gap)

Δgap=AG−12+HCO3

- Interpretation:

- If Δ gap < 22 mEq/L: Concurrent non-gap metabolic acidosis exists.

- If Δ gap > 26 mEq/L: Concurrent metabolic alkalosis exists.

MUDPILES (High Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis – HIGMA)

- M: Methanol

- U: Uremia

- D: Diabetic ketoacidosis

- P: Paraldehyde

- I: Infection, In therapy

- L: Lactic acidosis

- E: Ethanol, ethylene glycol

- S: Salicylates (aspirin)

Causes of Normal Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis (NAGMA)

- Excessive administration of 0.9% normal saline

- Gastrointestinal losses: Diarrhea, ileostomy, neobladder, pancreatic fistula

- Renal losses: Renal tubular acidosis

- Drugs: Acetazolamide

Lactic Acidosis

Definition and Types

- Lactic Acidosis: Elevated blood lactate levels > 2 mmol/L

- Type A: Impaired oxygen delivery (e.g., shock, hypoxia)

- Type B: Impaired oxygen utilization (e.g., mitochondrial dysfunction)

- Type D: Bacterial overgrowth

Pathophysiology

- Anaerobic Glycolysis: Pyruvate converted to lactate when oxygen is scarce

- Lactate Clearance: Liver and kidneys play major roles

Causes of Increased Lactate Production

- Hypoxia: Decreased oxygen delivery (e.g., cardiac arrest, sepsis)

- Increased Oxygen Demand: Exercise, seizures

- Impaired Clearance: Liver disease, renal failure

Treatment Approaches

- Address Underlying Cause: Oxygen delivery, removal of toxins

- Supportive Measures: IV fluids, bicarbonate in severe cases

Respiratory Acidosis Considerations

Increased CO2 Production

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Hyperthyroidism

- Sepsis

- Overfeeding

Decreased CO2 Elimination

- Intrinsic pulmonary disease: Pneumonia, ARDS, fibrosis, edema

- Upper airway obstruction: Laryngospasm, foreign body, OSA

- Lower airway obstruction: Asthma, COPD

- Chest wall restriction: Obesity, scoliosis, burns

- CNS depression: Anesthetics, opioids, CNS lesions

- Decreased skeletal muscle strength: Myopathy, neuropathy, residual effects of neuromuscular blocking drugs

- Rarely, an exhausted soda–lime or incompetent one-way valve in an anesthesia delivery system can contribute to respiratory acidosis.

Respiratory Alkalosis

Metabolic Alkalosis

Links

References:

- ICU One Pager. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://onepagericu.com/

- Hager HH, Burns B. Artery Cannulation. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482242/

- Pierre L, Pasrija D, Keenaghan M. Arterial Lines. [Updated 2024 Jan 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499989/

- Raj, T. D. (2017). Data interpretation in anesthesia.. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55862-2

- Chambers D, Huang CLH, Matthews G. Basic physiology for anaesthetists. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2015.

- Castro D, Patil SM, Zubair M, et al. Arterial Blood Gas. [Updated 2024 Jan 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536919/

- Soni KD. Ultrasound-guided arterial cannulation: what are we missing and where are we headed? Indian J Crit Care Med 2024;28:632-633. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11234131/ pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Card S, Piersa A, Kaplon A, et al. Infectious risk of arterial lines: a narrative review. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2023;37:2050-2056. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37500369/ pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Nethathe GD, Mbeki M. Heparin flush vs saline flush for maintenance of adult intra-arterial catheters: potential harm, too little gain? SAJAA 2016;22:70-71. Available from: https://www.sajaa.co.za/index.php/sajaa/article/view/1861 sajaa.co.za

- Rezaie S. Damping and arterial lines. REBEL EM blog. 4 Jul 2022. Available from: https://rebelem.com/damping-and-arterial-lines/ rebelem.com

- Williams C, Pasrija D, Pierre L, Keenaghan M. Arterial lines. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated 23 Mar 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499989/

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

ICU OP- ABG

ICU One pager Acid base

ICU One pager Lactic acidosis)

Acid/base

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “6918f516-b271-44d2-b561-0945cb2c03d1”