{}

Intraoperative Awareness

Definition

- Recall: Intraoperative consciousness in cases where unconsciousness is expected, and postoperative explicit recall of operative events.

- Intraoperative Awareness without Recall: Differentiated from recall by the absence of postoperative explicit memory.

Incidence and Impact

- Occurs in 1 to 2 cases per 1000 general anaesthetics (GAs).

- 43% of these cases develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Assessment

- Modified Brice Questionnaire:

- What is the first thing you remember after waking up?

- Do you remember anything between going to sleep and waking up?

- Did you dream during your procedure?

- Were your dreams disturbing you?

- What was the worst thing about your procedure?

Contributing Factors

- Inadequate anaesthetic dosing.

- Elevated anaesthetic requirements.

- Patients too ill to tolerate adequate levels of anaesthesia.

- Anaesthesia delivery system malfunctions.

Basics of EEG

Overview

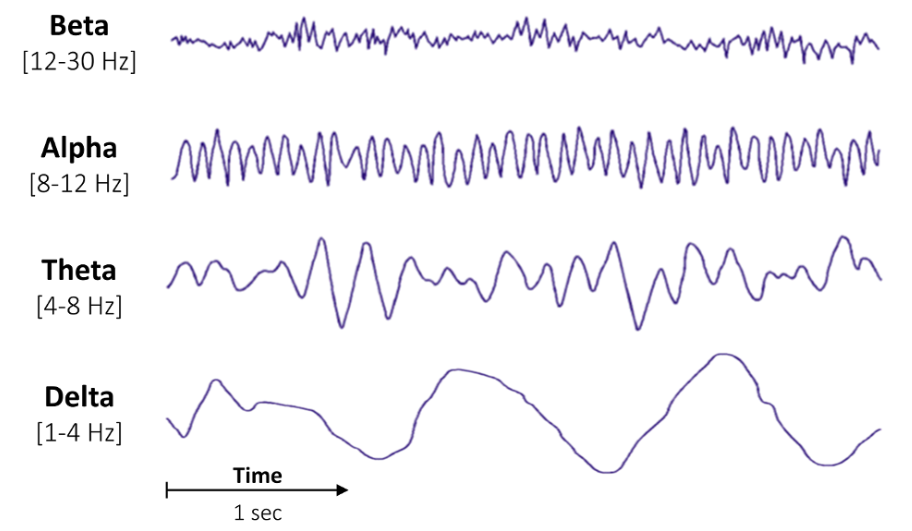

- Electrical Activity: Portrayed by waveforms with varying frequencies and amplitudes.

- Fourier Transformation: Deconstructs electrical activity into commonly recognized waveforms (α, β, θ, δ) associated with different levels of wakefulness.

Waveforms and Associated States

- β (Beta) Waves: Associated with wakefulness.

- δ (Delta) Waves: Associated with NREM sleep (stage 3) or general anaesthesia (GA).

Wave Frequency Categories

| Wave Category | Frequency (Hz) |

|---|---|

| δ (Delta) | 0.5-3.5 |

| θ (Theta) | 3.5-7.0 |

| α (Alpha) | 7.0-13.0 |

| β (Beta) | 13.0-30.0 |

Quantitative Analyses

- Time Domain:

- Describes how the waveform pattern changes over time.

- Burst Suppression Ratio: Proportion of time EEG activity is suppressed during a given interval, common in hypoxia, brain trauma, or high doses of anaesthetics.

- Frequency Domain:

- Describes EEG signal as a function of frequency.

- Power Spectral Density: Graphical representation of the Fourier transformation of the raw EEG, with frequency on the x-axis and power (amplitude squared) on the y-axis.

EEG Recordings

- Electrodes on the Scalp: Detect signals from cortical and subcortical regions.

- Subcortical Signals: More difficult to detect due to smaller potentials and rapid drop-off of electric field strength with distance.

- Cortical and Subcortical Interconnections: EEG signals reflect the state of both structures.

- Distinction: Signals (measurable at the scalp) vs. states (inferred from neuroanatomy and other information).

Physics of EEG

- Amplitude: Reflective of the power of the signal, measured in microvolts over time.

- Frequency: Measured in Hertz (Hz), describing the number of oscillations per second.

- Oscillation: Pattern that repeats over time, with sine waves as examples of perfect oscillatory signals.

Amplitude

- Higher amplitude indicates higher signal power.

BIS

BIS Algorithm Interpretation

The BIS (Bispectral Index) algorithm interprets raw EEG data gathered from forehead electrodes and provides anaesthesiologists with a dimensionless BIS value ranging from 0 to 100. The BIS value is derived by:

-

Removing Noise and Artifacts: Sources include:

- Electrocardiography (ECG)

- Electromyography (EMG) from facial muscle activity

- Peripheral nerve stimulators

- Electrocautery

-

Combining Parameters: After noise reduction, the algorithm combines several parameters:

- Burst Suppression Ratio

- QUAZI Suppression

- Beta Power (Relative Beta Ratio)

- Synchronisation of Low-Frequency Activity (SynchFastSlow)

Factors Affecting BIS Reliability

-

Electrode Placement and Adherence:

- Erroneous placement or decreased adherence of EEG leads can increase electrode impedance, potentially leading to falsely elevated BIS values.

-

Electromyographic (EMG) Activity and Electrical Devices:

- Facial EMG activity and certain electrical devices (e.g., electrical blades, pacemakers) can introduce high-frequency signal artifacts, falsely elevating BIS values.

-

Neuromuscular Blockers:

- Neuromuscular blockers may reduce EMG interference. However, their use may also eliminate awareness-related patient movements, which are critical warning signs of general anaesthetic underdosing.

- Muscle relaxants alone can cause spuriously low BIS values and should be used with caution.

-

Nitrous Oxide:

- Nitrous oxide can preserve alpha waves while suppressing low-frequency delta waves. The suppression of delta waves can contribute to falsely elevated BIS values calculated from the raw EEG data.

EEG Parameters and Their Significance

| Parameter | Type of Domain | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Burst suppression ratio | Time | Period of “fully suppressed” EEG |

| QUAZI suppression | Time | Period of “nearly suppressed” EEG |

| Relative β ratio | Frequency | Degree of high-frequency activation |

| SynchFastSlow | Frequency (bispectral) | Low-frequency synchronisation |

BIS Monitoring Parameters

| Parameter | Unit of Measurement | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| EMG (electromyogram) | Hz | Measurement of muscle activity. The BIS value becomes less reliable as the amount of muscle activity increases. |

| SEF95 (95th percentile of spectral edge frequency) | Hz | Frequency below which 95% of the total EEG power lies. This value decreases with increasing levels of general anaesthetics or opioids. |

| TP (total power) | dB | Summation of the power of the various component waves. |

| SQI (signal quality index) | Percentage | Quality of EEG signal, with 100% representing perfect signal quality and 0% poor signal quality. |

| SR (suppression ratio) | Percentage | Proportion of a 63-second time period during which EEG activity was suppressed (i.e., isoelectric). This value is inversely proportional to the BIS value. |

BIS Limitations

-

Awareness Under General Anesthesia:

- The use of BIS indices does not guarantee the prevention of awareness under general anesthesia.

-

Pediatric Reliability:

- BIS indices were developed from adult patient cohort data. The rapidly changing and developing brain during adolescence suggests differing responses to anesthesia compared to adults. Considerable evidence indicates EEG-based indices are less reliable in pediatric populations.

-

Neurophysiological Considerations:

- The calculation of BIS indices does not directly relate to the neurophysiology of how specific anesthetics exert their effects in the brain. Different anesthetics affect the brain in various ways, and assuming a uniform EEG pattern can cause inaccuracies. A specific BIS value does not consistently represent the same level of unconsciousness across different anesthetics.

-

Age-Related Variations:

- Physiological and cognitive changes that accompany aging can impact the accuracy of BIS indices. Elderly patients typically respond more quickly to lower doses of anesthetic compared to younger adults. BIS indices, constructed based on young adult cohorts, may not accurately portray the level of unconsciousness in elderly patients.

Anaesthetics and Effects on the Brain

-

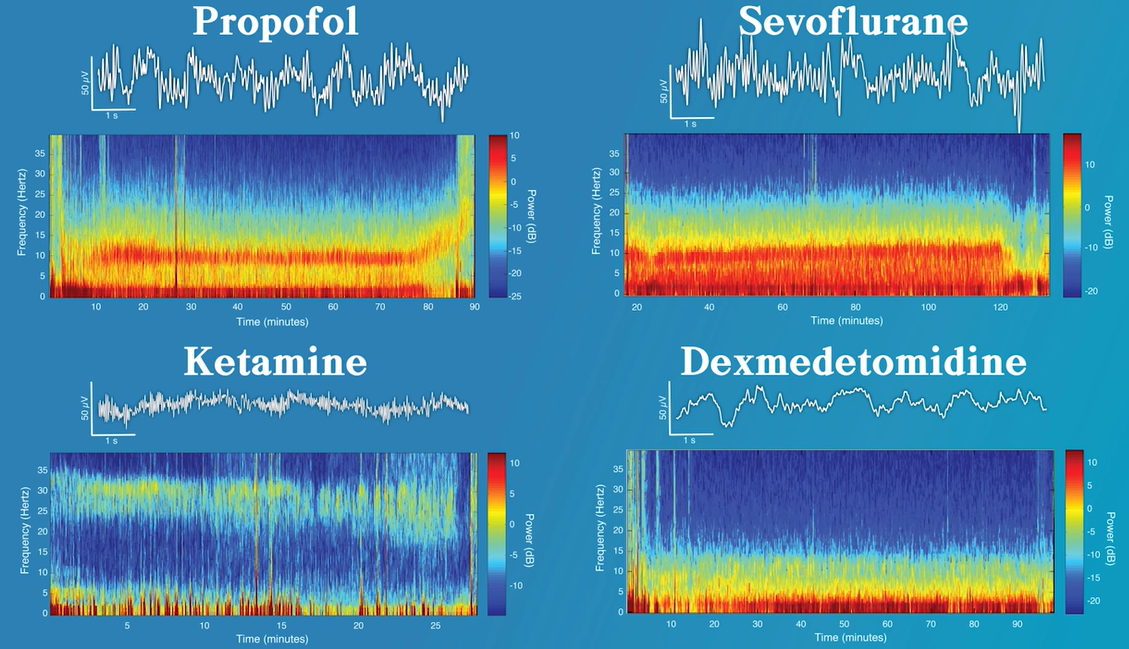

Anesthesia-Induced Oscillations:

- Anesthetics induce oscillations that alter or disrupt normal brain oscillations during information processing. These anesthesia-induced oscillations can be 5 to 20 times larger than the amplitudes exhibited in an awake state.

-

Variability Based on Anesthetic Type:

- The anesthesia-induced oscillations vary depending on the type of anesthetic used. Different anesthetics target various molecular structures and neural circuits, leading to distinct states of altered arousal.

Non-Awareness Applications of BIS Monitoring

- Shorter Recovery Times: Patients monitored with BIS tend to have shorter recovery times compared to those monitored clinically.

- Reduced Postanaesthetic Care Unit (PACU) Stay: BIS monitoring can decrease the length of PACU stay by approximately 7 minutes.

- Reduced Anesthetic Consumption: There is a decrease in the consumption of propofol, sevoflurane, and desflurane.

- Reduced Incidence of PONV: BIS monitoring reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

- Decreased Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: Particularly beneficial among at-risk patients, BIS monitoring helps in reducing postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

- Identification of High-Risk Patients: A study involving approximately 24,000 noncardiac surgery patients indicated that low mean arterial pressure (MAP < 75 mm Hg) combined with low minimum alveolar concentration (MAC < 0.80) and low BIS values (< 45) is associated with a significantly higher risk of 30-day mortality.

BIS Studies Summary

Comparison of BIS Monitoring Vs Standard Practice in Awareness Prevention

Sample Population and Intervention

B-Aware®

- Sample Population: 2,463 high-risk patients

- Intervention: BIS monitoring

- Control: Standard practice

B-Unaware®

- Sample Population: 2,000 high-risk patients

- Intervention: BIS goal < 50

- Control: End-tidal anesthetic concentration (ETAC) goal 0.7-1.3

BAG-RECALL

- Sample Population: 6,041 high-risk patients

- Intervention: BIS goal < 60

- Control: ETAC goal 0.7-1.3

Michigan Awareness Control Study

- Sample Population: 21,601 unselected surgical patients

- Intervention: BIS goal 40-60

- Control: ETAC goal > 0.7 MAC

Zhang Et Al. (2011)

- Sample Population: 228 patients undergoing total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA)

- Intervention: BIS goal 40-60

- Control: No BIS monitoring, standard practice

Primary Outcomes

| Study | Intervention Group | Control Group | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-Aware® | 2 cases of awareness (0.17%) | 11 cases of awareness (0.91%) | BIS monitoring reduced the incidence of awareness |

| B-Unaware® | 2 cases of awareness (0.12%) | 2 cases of awareness (0.12%) | No significant difference between BIS and ETAC groups |

| BAG-RECALL | 7 cases of awareness (0.12%) | 8 cases of awareness (0.14%) | No significant difference between BIS and ETAC groups |

| Michigan Awareness Control Study | 8 cases of awareness (0.038%) | 8 cases of awareness (0.046%) | No significant difference between BIS and ETAC groups |

| Zhang et al. (2011) | 4 cases of awareness (1.75%) | 16 cases of awareness (7.02%) | BIS monitoring reduced the incidence of awareness during TIVA |

Deep Dive Knowledge

Frequency Bands

Different EEG Waveforms Are Associated with Distinct Behavioural and Neurophysiological States Induced by Anesthetics

EEG Oscillations and Anaesthesia

-

Awake States:

- With eyes open, the EEG typically exhibits high-frequency oscillations in the beta (12–25 Hz) and gamma (25–80 Hz) ranges.

-

Propofol-Induced Sedation:

- When propofol is used for sedation, oscillations in the beta (12–25 Hz) range and the alpha (8–12 Hz) range are commonly observed. Additionally, there is an increase in waveform amplitude in the sedated and unconscious states compared to the awake state.

-

Propofol-Induced Unconsciousness:

- For surgical levels of unconsciousness induced by propofol, the EEG typically shows prominent slow/delta (0–4 Hz) and alpha (8–12 Hz) oscillations.

-

Isoelectricity:

- Isoelectricity, indicating brain inactivation, appears on the EEG as a flat line. This pattern is commonly observed in anesthetic-induced coma and profound hypothermia.

EEG Spectrogram

-

Transition from Awake to Unconscious:

- The transition from an awake to an unconscious state involves dramatic changes in the EEG signal. The amplitude of slow/delta oscillations can be 5 to 20 times larger than that of the gamma and beta oscillations seen in the awake state.

-

Spectrogram Explanation:

- The spectrogram mathematically decomposes the EEG signal into its individual frequency components and their power at each instant in time. The waveform is the time-domain representation, while the spectrogram is the frequency-domain representation.

- In a spectrogram plot:

- Time is displayed along the x-axis.

- Frequency is displayed along the y-axis.

- Power is indicated by color, with warmer colors representing greater power.

- Power is measured in decibels (dB), a logarithmic scale that highlights smaller features more effectively.

EEG Spectrogram Visual Representation

- The spectrogram would show a timeline along the x-axis, frequency ranges along the y-axis, and varying colours indicating the power of the frequency components.

- In an awake state, high-frequency oscillations in the beta and gamma ranges would dominate.

- As propofol-induced sedation occurs, the spectrogram would display an increase in power in the beta and alpha ranges.

- Upon reaching surgical levels of unconsciousness, the spectrogram would reveal prominent slow/delta and alpha oscillations with increased amplitude.

- Isoelectricity would appear as a flat line, indicating a lack of oscillatory activity.

EEG Spectrogram and Waveform Relationship

-

Spectral Analysis:

- In spectral analysis, a short segment of the EEG signal is decomposed into the power at each frequency within a specified range. Power reflects the amplitude of the wave.

- This decomposition creates a spectrum plot. For the example case, prominent frequency components are observed in the slow-delta and alpha bands.

-

Time-Dependent Spectrum:

- A single spectrum plot represents one segment of time. In the operating room (OR), it is crucial to observe the evolving pattern of the EEG.

- To achieve this, the spectrum is calculated at each instant in time, and successive spectrum plots are stacked together as time progresses, forming a 3-dimensional plot known as the spectrogram.

- The spectrogram has frequency, power, and time on the axes.

-

2-Dimensional Spectrogram:

- The spectrogram can also be displayed in 2 dimensions by removing the power axis and using color-coding to indicate power.

- This 2-dimensional representation is the most common way to display the EEG signal in the frequency domain.

Power and Oscillations

-

Oscillation Amplitude and Power:

- Oscillation amplitude is related to power. In the spectrogram, color indicates the power of the oscillation at a particular frequency. Warmer colors (e.g., yellow or red) represent higher power.

- An increase in oscillation amplitude appears as a shift to a warmer color in the spectrogram.

-

Power Calculation:

- Power at a given frequency is defined in decibels (dB) as 10 times the log base 10 of the squared amplitude:

Decibel Scale

- Logarithmic Nature: Color differences between blue and red indicate significant power differentials.

- 20 dB difference: Corresponds to a 10-fold difference in signal amplitude.

- 6 dB difference: Corresponds to a 2-fold difference in signal amplitude.

Oscillations

- Under 20 Hz: High power indicated by yellow and red coloring.

- 30 Hz and Above: Low power indicated by dark blue coloring.

- Alpha Frequency Range (8-12 Hz):

- As time progresses, the oscillations become more pronounced and constant, indicated by the transition to red color.

- This indicates an increase in power and amplitude of the oscillations.

Isoelectric State

- Definition: Characterized by a flat EEG pattern with low power oscillations across most frequencies, appearing as dark blue in the spectrogram.

Patterns with Different Agents

Propofol

- When propofol is being delivered for general anesthesia, the pattern that can be considered its characteristic EEG pattern is slow/delta (0.1 to 4 Hz) and alpha (8–12 Hz) oscillations.

- In the spectrogram this is viewed as high power (e.g. orange/red in color) centered around these two frequency ranges.

Typical Response

- When propofol is administered as a bolus for induction of general anesthesia, the EEG changes within 10 to 30 seconds from an awake pattern that typically consists of low-amplitude gamma and beta oscillations (i.e. high frequencies) to a pattern of high-amplitude slow and delta oscillations (i.e. low frequencies).

- In the EEG waveform this is observed as a transition to higher amplitude oscillations. In the EEG spectrogram, this appears as an increase in power between 0.1 to 5 Hz. This transition to a slow/delta pattern coincides with loss of responsiveness, loss of the oculocephalic reflex, apnea, and atonia

- As the initial, profound effects of the bolus doses of propofol recede, the EEG then evolves into a slow/delta and alpha oscillation pattern.

- The transition time from the slow/delta pattern to the combined slow/delta with alpha pattern depends on how profound the bolus dose effect was.

- This transition can take several minutes. This slow/delta with alpha is our typical propofol pattern and will continue as propofol is administered as an infusion to maintain general anesthesia.

- The slow/delta oscillation transitioning to the slow/delta plus alpha is the typical case. In other cases, particularly if large doses of propofol are administered rapidly, the patient may immediately enter burst suppression before transitioning to the slow/delta plus alpha pattern.

- Therefore, if more propofol was administered than required to induce unconsciousness, it will take longer to transition to the slow/delta and alpha pattern. (Propofol overdose)

Paradoxical Excitation

- An increase in beta oscillation activity can be observed during paradoxical excitation. During paradoxical excitation the patient may exhibit purposeless or defensive movements, incoherent speech, and euphoria or dysphoria. It is termed paradoxical because a state of excitation is being induced, rather than the intended unconscious state.

- Mechanism

- Increased excitatory inputs from the thalamus to the cortex, resulting from GABAA1-mediated inhibition of inhibitory inputs from the globus pallidus to the thalamus.

- Low-dose propofol induces transient blockade of slow potassium currents in cortical neurons.

Alpha Waves and Slow Oscillation Origin

- The alpha and slow/delta oscillations are related to the two mechanisms through which propofol is thought to induces unconsciousness.

- The alpha oscillations likely reflect dysfunction of thalamocoritcal communication that results from propofol enhancing inhibition in the cortex and thalamus.

- Meanwhile, the slow/delta oscillations reflect a disruption to neural spiking activity that causes an interruption of intracortical communication.

Emergence from Propofol

- As the patient emerges following discontinuation of the propofol infusion the typical slow/delta and alpha oscillation pattern is gradually replaced by higher-frequency beta/gamma oscillations with lower amplitudes. As the amplitude of the slow/delta oscillations dissipate the EEG waveform begins to flatten.

- In the spectrogram, the transition from the typical propofol pattern to the beta/gamma oscillations appears as a “zipper opening” pattern. The decrease in oscillation amplitude is observed as a shift in the power of the oscillations, noted by the color transitioning from red to yellow.

- The return of high-frequency power in the EEG is consistent with the return of normal cortical activity and indirectly with the return of normal thalamic and brainstem activity.

Dexmedetomidine

- The effects of dexmedetomidine on arousal are primarily due to its action on presynaptic α2 adrenergic receptors projecting from the locus ceruleus.

- When dexmedetomidine binds to the α2 receptors it hyperpolarizes the locus ceruleus neurons, decreasing norepinephrine release.

- While burst suppression can be common in cases where high doses of propofol, the barbiturates, or the inhaled ether drugs are being delivered, delivery of dexmedetomidine is not often associated with burst suppression.

- Dexmedetomidine is notable for its ability to provide sedation with minimal risk of respiratory depression. However, in the operating room it is commonly used as an anesthetic adjunct because when being used to provide sedation patients are easily arousable. In addition, when being administered for procedural sedation the typical EEG pattern associated with dexmedetomidine closely resembles nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep stage III, or slow-wave sleep. The EEG pattern of both slow-wave sleep and dexmedetomidine sedation are characterized by slow/delta oscillations.

- MOA

- Dexmedetomidine blocks the release of norepinephrine (NE) from neurons projecting from the locus ceruleus (LC) to the preoptic area (POA) of the hypothalamus, basal forebrain (BF), the intralaminar nucleus (ILN) of the thalamus, and the cortex.

- Hyperpolarization of the locus ceruleus neurons result in loss of inhibitory inputs to the preoptic area of the hypothalamus. The loss of these inhibitory inputs to the preoptic area mean the inhibitory pathways from the preoptic area to the arousal centers become activate, leading to decreased arousal.

- The blockage of norepinephrine release also results in the loss of excitatory inputs from the locus ceruleus to the basal forebrain, intralaminar nucleus of the thalamus, and cortex, resulting in decreased thalamocortical connectivity. This action further enhances the sedative effect of dexmedetomidine.

Waveforms

- Alpha oscillations are not a feature of dexmedetomidine sedation. At low-dose infusions, the EEG pattern for dexmedetomidine shows a combination of slow/delta oscillations with spindles.

- As the dose increases the spindles disappear and the amplitude/power of the slow/delta oscillations increase.

- When dexmedetomidine is administered and the EEG signal has spindles it indicates a state of light sedation. The patient is likely to responded to verbal queries and in response to light tactile stimulation.

Spectrogram

- At low-doses, the typical EEG pattern for dexmedetomidine is a combination of slow/delta oscillations and spindles

- In the spectrogram the spindles appear as intermittent streaks in the high alpha and low beta ranges. The slow/delta oscillations appear as power between 0 to 4 Hz. As the dose increases the spindles become smaller and the amplitude of the slow/delta oscillations increases.

- As the infusion rate of dexmedetomidine delivery increases the amplitude of the slow/delta oscillations increase and the amplitude of the spindles may decrease. This pattern should indicate the patient is unresponsive to verbal queries, but they will likely move in response to changes in the level of nociceptive stimulation.

Spindles

- When using dexmedetomedine for sedation, spindles are intermittent bursts of activity, with each burst lasting about 1 to 2 seconds.

- The bursts occur within a frequency range of 9 to 15 Hz, which corresponds to high alpha and low beta frequency bands. While this is a similar frequency range as the alpha oscillations seen with propofol, they have much less power than alpha oscillations. The appearance of spindles is consistent with a light state of dexmedetomidine sedations.

Ketamine

- The effects of ketamine on arousal are primarily by binding to NMDA receptors in the brain and spinal cord. When bound to NMDA receptors, ketamine functions as a channel block

- MOA

- As a channel blocker, ketamine’s effect is most profound on ion channels that are typically open/active during normal consciousness functioning. In general, the ion channels of the inhibitory interneurons of the cortex are more active than those on pyramidal neurons. As such, the EEG dynamics and behavioral responses observed with ketamine are likely the result of the blocking of inputs to inhibitory interneurons in the cortex.

- By blocking the activity of these inhibitory interneurons, these neurons are no longer providing inhibitory signals to the downstream excitatory neurons they communicate with. Without inhibition, these excitatory neurons become disinhibited and are allowed to become more active.

- Administration of low-dose ketamine leads to the disinhibition of excitatory neurons, which allow them to become more active. This increase in activity also increases cerebral metabolism.

- Rather than suppressing communication, it is thought that ketamine allows brain regions such as the cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala to continue communicating, but with less modulation and control by the inhibitory interneurons. In this case, information might continue to be processed, but without proper coordination in space and time.

- The would result in the hallucinations, dissociative states, euphoria, and dysphoria commonly observed with low-dose ketamine.

- Other effects

- Disruption of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex due in part to increased glutamate activity at non-NMDA glutamate receptors.

- Blockage of glutamate release from neurons in the dorsal root ganglia. The dorsal root ganglia is the first synapse of the pain pathway in the spinal cord, where glutamate is the primary neurotransmitter. This likely plays a part in the analgesia effects of ketamine.

- Excitatory glutamatergic neurons are blocked as the dose of ketamine is increased.

Low Dose Ketamine

- Low-dose ketamine (~0.5 mg/kg) is associated with an active EEG signal. This can be attributed to the its effect of disinhibiting excitatory neurons, resulting in increased cerebral metabolic rate, cerebral blood flow, and hallucinations.

- When administered alone at low doses, the typical EEG pattern associated with ketamine sedation is a fast oscillation in the high beta, low gamma range (i.e. between 25 and 32 Hz).

- This is a more active signal than observed during the administration of other anesthetics such as propofol, dexmedetomidine, and the inhaled ether derivatives. When compared with propofol and dexmedetomidine, slow/delta oscillations appear less regular during ketamine administration.

Inhaled Anaesthetics

- MOA

- Binding to GABAA receptors and enhancing GABAergic inhibition.

- Blockage of two-pore potassium channels and hyperpolarizing-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels.

- Blocking glutamate release by binding to NMDA receptors.

Waveform

- The EEG patterns for the inhaled ether anaesthetics most closely resemble the pattern associated with propofol. At surgical levels of general anaesthesia the EEG exhibits slow/delta oscillations and alpha oscillation.

- This is similar to those of propofol suggesting that the dominant mechanism of action (i.e. enhanced GABAergic inhibition) may be same for both the inhaled ether anaesthetics and propofol.

- However, unlike propofol, when sevoflurane is administered at approximately the minimum alveolar concentration (MAC), or greater, a strong theta oscillation (4 to 8 Hz) is also present.

- This may reflect one of the non-GABAergic mechanisms of how the inhaled ether anaesthetics effect arousal.

- At sub-minimal alveolar concentrations (MACs) of sevoflurane the typical EEG pattern is strong slow/delta and alpha oscillations.

- As the concentration of sevoflurane is increased to MAC levels or above, a strong theta oscillation (4 to 8 Hz) can appear. In the spectrogram this appears as a distinctive pattern of power spanning from the slow oscillation range up through the alpha range.

- As the concentration of sevoflurane is increased to MAC levels, the signal transitions to include this theta “fill in” pattern.

- The appearance of theta oscillations, that span from the slow oscillation range to the alpha range, appear as the concentration of the ether derived anaesthetics increase to MAC levels and above. At sub-MAC levels the EEG signal doesn’t tend to feature this theta fill-in pattern.

N20

- Nitrous oxide delivered on its own (with oxygen) is most commonly associated with increased beta and gamma oscillations. It is possibly also associated with a relative decrease in slow/delta and theta oscillations.

- transitioning from sevoflurane to nitrous oxide is initially associated with slow/delta oscillations.

- Upon reducing delivery of sevoflurane and starting nitrous oxide delivery, the EEG signal transitions to profound slow/delta oscillations. There is a near complete loss of power of all frequencies above approximately 10 Hz. After the sevoflurane has been stopped, the slow/delta pattern evolves into the beta and gamma oscillations more commonly associated with nitrous oxide.

Burst Suppression

- Many anesthetics, including propofol, the barbiturates, and the inhaled ether drugs will commonly result in burst suppression when delivered in sufficiently high doses. Anesthetics such as ketamine, dexmedetomidine, remifentanil, and nitrous oxide do not produce burst suppression.

- Burst suppression is a profound state of anesthetic-induced brain inactivation. It is particularly common in elderly patients. In the EEG, burst suppression appears as an alternating pattern of electrical quiescence (suppression) and electrical activity (bursts).

- While burst suppression is a state we should typically avoid, since it is not required to maintain unconsciousness and has been associated with poor cognitive outcomes, it is sometimes necessary in specific clinical situations. During surgeries requiring total circulatory arrest, a state of burst suppression is induced by hypothermia. In the intensive care unit, burst suppression may be induced to place a patient in a medically induced coma for cerebral protection to treat intracranial hypertension or status epilepticus.

- In the EEG spectrogram, burst suppression appears as an alternating vertical line pattern as the EEG switches between periods of low power (suppression) and periods of high power (bursts).

- If a patient is in burst suppression, as the dosage is further increased, the length of the suppression periods between bursts increases. The dosage can be increased to a point in which the EEG becomes completely isoelectric.

- The burst suppression ratio, or suppression ratio, measures the fraction of time within a given time interval that the EEG is suppressed. It is expressed as a number between 0 and 1, with a value of 1 indicating the patient was in a state of suppression for the entire interval.

- The burst suppression probability is an alternate metric that measures the instantaneous probability of the brain being in a state of suppression. It is intended to track burst suppression in real-time. It is also expressed as a number between 0 and 1, with 1 indicating the patient has a 100% probability of being suppressed at that instant in time.

Artifacts

- Muscle artifacts occur due to the electrical fields generated by muscles and through movement of the electrode itself. It typically appears in the EEG as high frequency, high amplitude noise that begins and ends abruptly.

- Use of electrosurgical devices, such as cautery, can produce sudden spikes of activity in the EEG due to application of the cautery effect. Sometimes this artifact can be reduced by moving the ground pad for the cautery device further away from the patient’s head (e.g. placing it on the leg).

- Use of a peripheral nerve stimulator, also called the “train of four”, attached to a patient’s face, can result in a very brief spike in the EEG, occurring every ~15 seconds. When in a standby mode, and not actively delivering stimulation, the train of four nerve stimulator regularly sends an electrical current to the contacts to test the impedance. This impedance test occurs approximately every 15 seconds and hence the artifact observed in the EEG. Turning the nerve stimulator off when not in use, rather than leaving it in a standby mode, can remove this artifact.

Old Teaching

This method is quickly being phased out of using BIS, the modern use focuses on the use of raw EEG and DSA as described above. It is included here for completeness

Guide to Using BIS During the Maintenance Phase of TIVA

1. Assess Signal Reliability

- Signal Reliable?

- Yes: Continue with current anesthetic regimen.

- No: Assess/address reasons (e.g., leads misplaced, electrical interference).

2. BIS Value Assessment

-

BIS Value Between 40-60

- Yes: Monitor for concurrent changes in surgical stimulus and/or clinical signs (e.g., elevated heart rate, blood pressure, patient moving). These may suggest a need to increase the anesthetic dose.

-

BIS Value > 60

- Concurrent changes in surgical stimulus and/or clinical signs (e.g., elevated heart rate, blood pressure, patient moving) may suggest the need to increase the anesthetic dose.

- Potential False Elevation:

- Mechanical interference (e.g., EMG, electrocautery).

- Recent administration of anesthetic agents that increase BIS values (e.g., ketamine).

-

BIS Value < 40

- Concurrent changes in surgical stimulus and/or clinical signs (e.g., decreased heart rate or blood pressure) may suggest the need to decrease the anesthetic dose.

- Potential False Decrease:

- After administration of a paralytic agent.

- Consider acute decreases in blood pressure, temperature, and blood glucose in the absence of acute changes in surgical stimulus or anesthetic dose.

Links

References:

- Mathur S, Patel J, Goldstein S, et al. Bispectral Index. [Updated 2023 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539809/

- Raj, T. D. (2017). Data interpretation in anesthesia.. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55862-2

- Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Fawcett LJ, Punjasawadwong Y. Bispectral index for improving intraoperative awareness and early postoperative recovery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Sep 26;9(9):CD003843. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003843.pub4. PMID: 31557307; PMCID: PMC6763215.

- International Anesthesia Research Society. (2017). EEG for Anesthesia. Retrieved from https://eegforanesthesia.iars.org/

- Purdon, P. L., Sampson, A. L., Pavone, K. J., & Brown, E. N. (2015). Clinical electroencephalography for anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology, 123(4), 937-960. https://doi.org/10.1097/aln.0000000000000841

- Chang, B., Raker, R., & García, P. S. (2019). Bispectral Index Monitoring and Intraoperative Awareness. Anaesthesia Tutorial of the Week, 416. Retrieved from https://resources.wfsahq.org/atotw/bispectral-index-monitoring-and-intraoperative-awareness/

- Ryalino, C., Sahinovic, M. M., Drost, G., & Absalom, A. R. (2024). Intraoperative monitoring of the central and peripheral nervous systems: a narrative review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 132(2), 285-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2023.11.032

Summaries:

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “43c5530b-afb3-474f-8fc7-42c31612f475”