{}

Neck of Femur (Hip) Fracture

Epidemiology

- Incidence: ≈ 70 000 hip fractures occur annually in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and numbers are projected to rise with an ageing population. Women account for ~75 % of cases owing to higher rates of osteoporosis.

- Median age: ~ 80 years (IQR 76–87).

- Mortality: National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD) case‑mix‑adjusted 30‑day mortality in 2023 was 5–6 %; contemporary studies report 1‑year mortality 20–25 %.

- Functional impact: < 35 % of survivors regain pre‑fracture mobility; ~30 % experience ≥ 1 postoperative complication (delirium 28 %, pneumonia 12 %, heart failure 6 %).

Key Predictors of Poor Outcome

| Modifiable factor | Evidence & effect | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Surgery delay > 24 h | Linear rise in 30‑day mortality beyond 24 h; odds ratio 1.41 at 48 h | Prioritise theatre, use expedited pathways |

| Inadequate analgesia | Opioid‑related delirium & hypoventilation | Early fascia‑iliaca compartment block (FICB) + paracetamol & regional techniques |

| Delirium risk | Age > 80 yr, dementia, infection, polypharmacy | Multi‑component prevention bundle, minimise benzodiazepines |

Surgical Management

| Fracture pattern | Standard procedure | Anaesthetic note |

| Undisplaced intracapsular | Cannulated hip screws | Short procedure; low blood loss |

| Displaced intracapsular | Cemented hemi‑arthroplasty if or limited mobility; total hip arthroplasty if independent ambulators | Cement pressurisation causes embolic & hypotensive events–invasive A‑line advisable |

| Inter‑ / subtrochanteric | Sliding hip screw (DHS) or intramedullary nail | Longer surgery; higher blood loss |

Anaesthetic Considerations

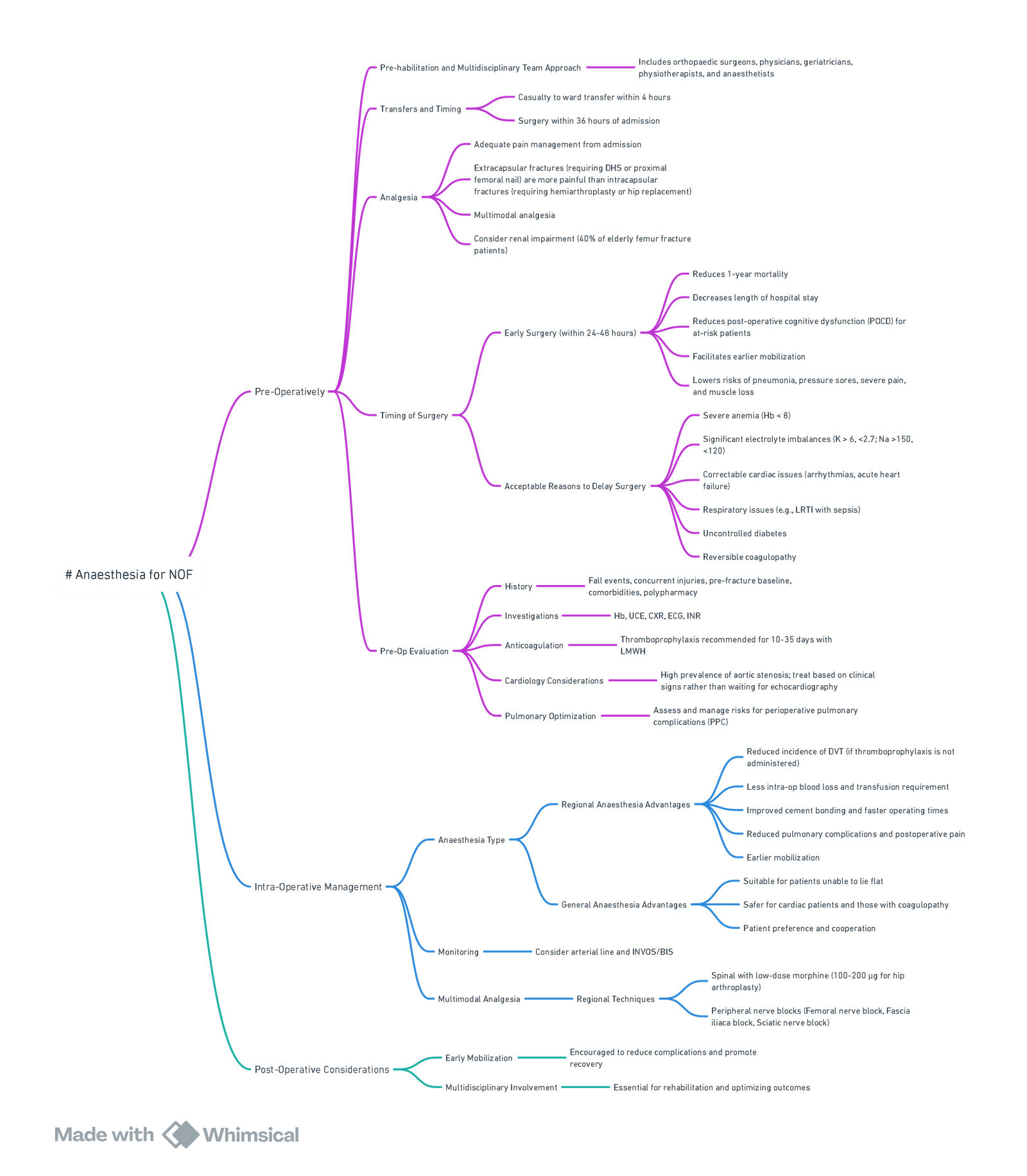

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Pre‑operative

- Multidisciplinary hip fracture programme (orthogeriatrician, anaesthetist, physiotherapist, dietitian) from admission as per NICE CG124 (updated 2023).

- Analgesia: ultrasound‑guided supra‑inguinal FICB (20 mL 0.25 % levobupivacaine; max 2 mg kg⁻¹) in ED reduces pain and opioid use.

- Optimisation: correct dehydration, anaemia (Hb < 10 g dL⁻¹), electrolyte imbalance; stop direct oral anticoagulants where safe (consult local protocol); screen for cognitive impairment (Abbreviated Mental Test Score, AMTS).

Intra‑operative

| Aspect | Current evidence‑based approach |

|---|---|

| Anaesthetic technique | The REGAIN trial (n = 1600) showed no difference in 60‑day mortality or delirium between spinal anaesthesia (SA) and GA; choice should be individualised. |

| Spinal | 0.5 % heavy bupivacaine 1.6–2 mL ± intrathecal morphine 50–100 µg; atraumatic 25 G needle; sedation with propofol or dexmedetomidine (avoid midazolam). |

| GA | Short‑acting agents (TIVA or volatile) with opioid‑sparing; depth‑of‑anaesthesia monitoring in frail patients; prophylactic anti‑emetics. |

| Haemodynamics | Maintain MAP > 65 mmHg; treat hypotension promptly with phenylephrine 50–100 µg or norepinephrine infusion 0.02–0.1 µg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹. |

| Temperature | Forced‑air warming and fluid warmers; hypothermia doubles wound‑infection risk. |

Post‑operative

- Early mobilisation within 24 h with physiotherapy reduces mortality and pressure‑ulcer risk.

- Analgesia: continue paracetamol 1 g 6‑hourly, NSAID if not contra‑indicated, and consider continuous FICB (0.2 % ropivacaine 5 mL h⁻¹) or IV oxycodone PCA.

- Delirium surveillance: 4‑hourly Confusion Assessment Method (CAM); treat underlying triggers.

- Secondary prevention: osteoporosis assessment and initiation of bone‑protective therapy before discharge.

Nottingham Hip Fracture Score (NHFS)

Validated external studies confirm NHFS AUC ≈ 0.79 for 30‑day mortality—superior to ASA grade

| Variable | Points |

|---|---|

| Age 66–85 yr | 3 |

| Age ≥ 86 yr | 4 |

| Male sex | 1 |

| Haemoglobin ≤ 10 g dL⁻¹ | 1 |

| AMTS ≤ 6/10 | 1 |

| Care‑home resident | 1 |

| ≥ 2 significant comorbidities | 1 |

| Active malignancy | 1 |

Interpretation

| NHFS total | Predicted 30‑day mortality |

| 0–2 | < 3 % |

| 3–4 | 3–6 % |

| 5–6 | 10–15 % |

| 7–8 | 23–33 % |

| 9–10 | > 45 % |

NHFS ≥ 5 should prompt senior anaesthetist involvement, invasive monitoring and early postoperative HDU/ICU bed planning.

Summary of Best‑practice Bundle

- FICB within 30 min of ED arrival.

- Orthogeriatric review on admission day.

- Surgery within 24 h of presentation once medically fit.

- SA or GA selected to optimise haemodynamic stability; opioid‑sparing.

- Maintain MAP > 65 mmHg, Normothermia and Hb > 8 g dL⁻¹.

- Multimodal analgesia and delirium prevention.

- Mobilise Day 1 and start bone‑health interventions.

Regional Anaesthesia for Hip Fracture

Why Regional Techniques Matter in hip‐fracture Pathways

Early nerve blockade reduces severe nociceptive pain, facilitates patient positioning for spinal anaesthesia, attenuates sympathetic stress responses and lowers the incidence of opioid-related delirium. Recent guidelines (NICE CG124 2023, BOA/RA-UK 2024) now regard early ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve block as a quality-of-care indicator for all hip-fracture admissions.

Essential Anatomy: Nerve Supply to the Hip

- Effective analgesia for hip fractures targets the articular innervation of the anterior hip capsule, primarily supplied by:

- Femoral nerve (L2–L4): via branches to the iliacus and directly to the anterior hip joint.

- Obturator nerve (L2–L4): articular branches to the inferomedial anterior hip capsule.

- Accessory obturator nerve (variable, present in ~10–30%): contributes to anterior capsule innervation.

- Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (L2–L3): innervates the skin overlying the lateral thigh and hip—important for surface analgesia.

- Superior gluteal and sciatic nerves (L4–S1): contribute to posterior capsule innervation but are less clinically relevant for fracture pain.

- Key Concept: The anterior capsule is the primary pain generator in hip fracture—making femoral, obturator, and accessory obturator nerves the most critical targets.

What’s New? (evidence 2019–2025)

| Technique | Key 2023-25 evidence | Main findings | Practical pearls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supra-inguinal fascia-iliaca block (s-FICB) | 11-RCT meta-analysis, 915 pts (Li 2024) | ↓ 24 h morphine by 11 mg oral morphine equivalents (OME), NRS pain ↓ 1.5 points for fractures; no ↑ complications; certainty = moderate | 30–40 mL 0.25 % levo-bupivacaine deposited cranial to inguinal ligament; simple to teach in ED |

| Pericapsular nerve-group (PENG) block | Double-blind RCT, 110 pts PFNA (Wu 2024) | ↓ 48 h sufentanil 15 %; better dynamic pain to 48 h; easier sitting for spinal | 20 mL LA between psoas tendon & pubic ramus; spare quadriceps strength |

| s-FICB vs PENG RCT, 120 pts pre-op (Huang 2024) | Equivalent static pain; PENG superior for movement; both out-performed opioids alone | Consider PENG if early mobilisation priority | |

| Network meta-analysis of pre-op blocks | 46 RCTs, 3 200 pts (Hayashi et al., Ann Emerg Med 2024) | All blocks beat systemic opioids for 2-h pain; PENG ranked first, s-FICB second; no block shortened LOS | Choose high-volume fascia-plane technique when expertise limited |

| Continuous FICB catheter | Propensity-matched cohort, 80 pts (Xu 2025) | Continuous 0.2 % ropivacaine 5 mL h⁻¹ → 25 % lower Was, 60 % reduction in POD, better 1-month Harris Hip Score | Tunnel lateral to ASIS; secure with glue; review at 48–72 h |

| Delirium prevention | Meta-analysis 18 RCTs, 1 540 pts (Review 2024) | FICB (single or continuous) ↓ postoperative delirium risk RR 0.63 | Dose opioid sparingly once block working |

| Lumbar erector spinae plane block (L-ESPB) | RCT, 90 pts inter-trochanteric # (Balaban 2025) | L-ESPB 30 mL 0.375 % ropivacaine ↓ 24 h morphine by 33 % vs lumbar-plexus block, preserved quadriceps | Useful when anterior approach contra-indicated (surgical dressings, stoma) |

| Quadratus lumborum block (QLB)–emerging | Small RCTs 2023-24 suggest QLB ≈ PENG for early pain and opioid use, with added benefit on sleep quality; evidence still low certainty | Reserve for practitioners experienced with posterior abdominal wall sono-anatomy |

Take-home Recommendations (2025 consensus)

- Give a block in ED within 30 min of triage–s-FICB or PENG preferred; 40 mL 0.25 % levobupivacaine provides ≈ 12 h analgesia.

- Supra-inguinal over infra-inguinal FICB–better supra-inguinal spread to obturator nerve and superior analgesia.

- Consider PENG when quadriceps sparing or difficult spinal positioning is crucial.

- Add a catheter if surgery likely to be delayed > 24 h or for frail patients at high delirium risk.

- Blocks are adjuncts, not replacements–continue scheduled paracetamol, minimal-dose opioids, and early mobilisation physiotherapy.

Links

Past Exam Questions

Nerve Blocks for Postoperative Pain Management in Hip Replacement

A 75-year-old woman sustained a neck of femur fracture. She is scheduled for a total hip replacement. You plan to perform a nerve block to assist with pain management post-operatively.

a) List the blocks that may be useful in this situation. (4)

b) Describe the performance of a femoral nerve block using ultrasound guidance and a nerve stimulator. In your description, include the precautions you would take to decrease the risks of nerve injury and intravascular injection. (6)

References:

- National Hip Fracture Database. NHFD annual report 2024: A broken hip—three steps to recovery. Royal College of Physicians; 2024. (nhfd.co.uk)

- Al‑Khateeb N, et al. Age, BMI, age/BMI ratio and NHFS as predictors of mortality following hip fracture. Cureus. 2024;16:e13832. (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Garnavos N, et al. Wait time and 30‑day mortality in adults undergoing hip fracture surgery: population‑based cohort study. JAMA. 2017;318:1994‑2003. (jamanetwork.com)

- Smith M, et al. Fascia‑iliaca block for hip fractures in the emergency department: systematic review and meta‑analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78:309‑320. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Zhou Y, et al. Supra‑inguinal fascia iliaca block for hip fracture analgesia: randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38:1058‑1065. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Regional versus General Anaesthesia for Promoting Independence after Hip Fracture (REGAIN) Investigators. Spinal or general anaesthesia for hip‑fracture surgery in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2025‑2035. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Sun L, et al. Validation of the Nottingham Hip Fracture Score in predicting postoperative outcomes. Orthop Surg. 2023;15:1096‑1103. (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- Guay, J., Parker, M. J., Gajendragadkar, P. R., & Kopp, S. L. (2016). Anaesthesia for hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd000521.pub3

- Liu, K., Chan, T. C., & Irwin, M. (2021). Anaesthesia for fractured neck of femur. Anaesthesia &Amp; Intensive Care Medicine, 22(1), 24-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2020.11.005

- Shelton, C. and White, S. (2020). Anaesthesia for hip fracture repair. BJA Education, 20(5), 142-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2020.02.003

Summaries:

Elderly

Hip fractures

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “21b395e4-1bbd-42c8-9d05-068b26f3aa9f”