- Stress Response

- Definition

- Endocrine Response

- Metabolic Sequelae of the Endocrine Response

- Activation of the Stress Response

- Minimally Invasive Surgery

- The Effect of Anesthesia on the Stress Response to Surgery

- Harmful Effects of Stress Response

- Links

{}

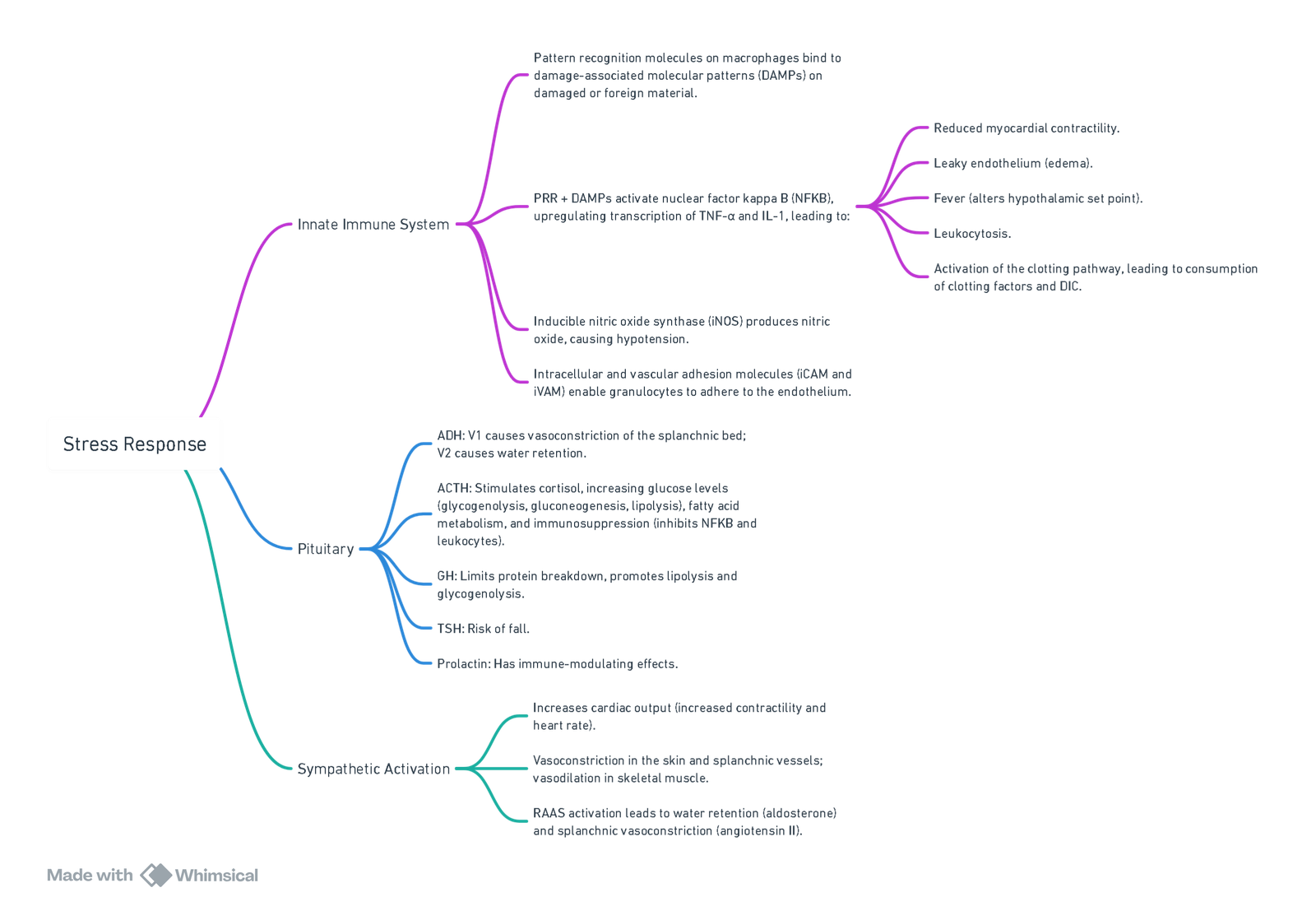

Stress Response

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Definition

- Hormonal and metabolic changes that follow injury or trauma.

- The stress response developed to allow injured animals to survive by catabolizing their stored body fuels. This response is unnecessary in current surgical practice.

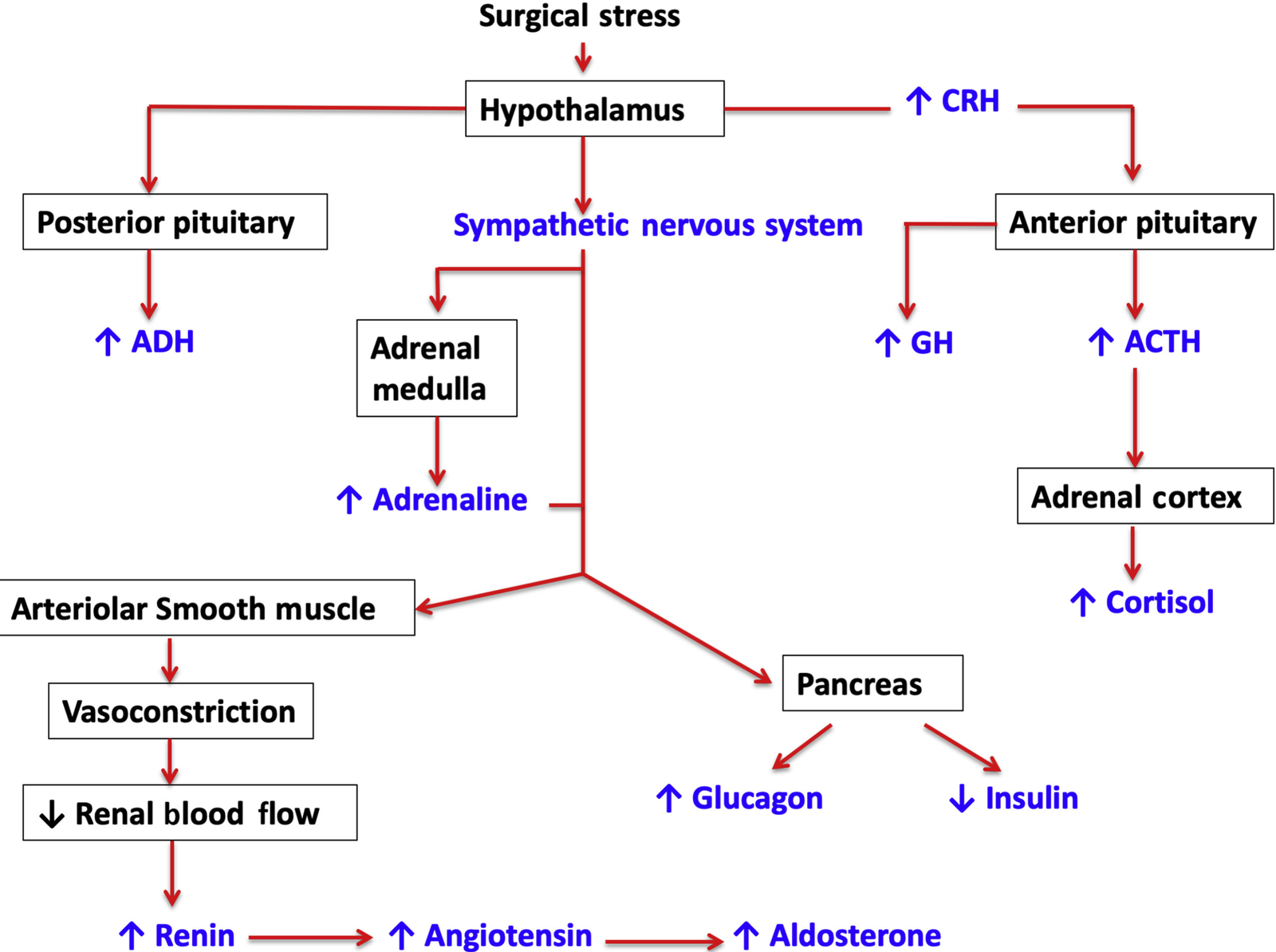

Endocrine Response

- Increased secretion of pituitary hormones and activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

- Changes in pituitary secretion have secondary effects on hormone secretion from target organs.

Systemic Responses to Surgery

Sympathetic Nervous System Activation

Endocrine ‘Stress Response’

- Pituitary hormone secretion

- Insulin resistance

Immunological and Haematological Changes

- Cytokine production

- Acute phase reaction

- Neutrophil leucocytosis

- Lymphocyte proliferation

Principal Hormonal Responses to Surgery

| Endocrine Gland | Hormones | Change in Secretion |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior Pituitary | ACTH | Increases |

| Growth hormone | Increases | |

| TSH | May increase or decrease | |

| FSH and LH | May increase or decrease | |

| Posterior Pituitary | ADH | Increases |

| Adrenal Cortex | Cortisol | Increases |

| Aldosterone | Increases | |

| Pancreas | Insulin | Often decreases |

| Glucagon | Usually small increases | |

| Thyroid | Thyroxine, tri-iodothyronine | Decrease |

Sympathoadrenal Response

- Hypothalamic activation of the sympathetic autonomic nervous system results in increased secretion of catecholamines from the adrenal medulla and release of norepinephrine from presynaptic nerve terminals.

- Norepinephrine is primarily a neurotransmitter, but some spillover into the circulation occurs.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

- Pituitary synthesizes corticotrophin or adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) as part of a larger precursor molecule, pro-opiomelanocortin.

- The precursor is metabolized within the pituitary into ACTH, β-endorphin, and an N-terminal precursor.

TSH, LH, and FSH

- Do not change markedly during surgery.

Vasopressin

- Increases significantly.

- Acts as an antidiuretic hormone.

Cortisol

- Surgery is a potent activator of ACTH and cortisol secretion.

- Increases rapidly following the start of surgery.

- Normally, increased concentrations of circulating cortisol inhibit further secretion of ACTH, but this feedback mechanism is ineffective after surgery, leading to high levels of both hormones.

- Cortisol release during surgery:

- Basal: 8-10mg/day

- Minor surgery: 50mg/day (baseline <24hrs)

- Major surgery: 75-100mg/day (baseline ± 5 days)

- Major trauma: up to 200-500mg/day (rarely >200mg 24 hours post-event)

- Exogenous steroids suppress the HPA axis, preventing a stress response and showing signs of HPA axis suppression.

Growth Hormone (GH)

- Also known as somatotrophin.

- Plays a major role in growth regulation, particularly in the perinatal period and childhood.

- Many actions are mediated through IGF-1 (produced in liver, muscle).

- Stimulates protein synthesis, inhibits protein breakdown, promotes lipolysis, and has an anti-insulin effect.

- Secretion increases with the extent of injury.

β-Endorphin and Prolactin

- Produced from the precursor molecule proopiomelanocortin.

- No major metabolic activity.

Insulin and Glucagon

- Insulin concentrations may decrease after induction of anesthesia. During surgery, there is a failure of insulin secretion to match the catabolic, hyperglycemic response, partly due to α-adrenergic inhibition of β-cell secretion and insulin resistance.

- Glucagon promotes lipolysis and gluconeogenesis but does not significantly contribute to hyperglycemia.

Thyroid Hormones

- Stimulate oxygen consumption in most metabolically active tissues except the brain, spleen, and anterior pituitary gland.

- Increase carbohydrate absorption from the gut and stimulate the nervous system.

- Thyroid hormones and catecholamines are closely associated, with the former increasing the number and affinity of β-adrenoceptors in the heart, enhancing sensitivity to catecholamines.

- Total and free T3 concentrations decrease post-surgery and return to normal after several days.

Metabolic Sequelae of the Endocrine Response

- Net effect is increased secretion of catabolic hormones.

Carbohydrate Metabolism

- Hyperglycemia

- Cortisol and catecholamines increase glucose production via hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, associated with insulin resistance.

- Related to the intensity of the surgical injury.

- Hyperglycemia persists due to catabolic hormones promoting glucose production and a relative lack of insulin along with peripheral insulin resistance.

Proteolysis

- Stimulated by increased cortisol concentrations.

- Results in significant weight loss and muscle wasting post-major surgery or trauma.

Lipolysis

- Stimulated by cortisol, catecholamines, and GH, and inhibited by insulin.

- Increases mobilization of triglycerides, although plasma concentrations of glycerol and fatty acids may not change significantly.

- Glycerol from lipolysis serves as a substrate for hepatic gluconeogenesis. Fatty acids are oxidized in the liver and muscle or converted to ketone bodies.

Water and Electrolyte Metabolism

- Increased vasopressin secretion may continue for 3-5 days depending on the severity of the surgical injury and development of complications.

- Renin is secreted from the juxtaglomerular cells of the kidney due to increased sympathetic activation, promoting Na+ and water reabsorption.

Activation of the Stress Response

Afferent Neural Impulses

- Afferent neuronal impulses from the injury site travel along sensory nerve roots through the dorsal root of the spinal cord to the medulla, activating the hypothalamus.

Cytokines

- Major cytokines released post-major surgery include interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and IL-6.

- Cytokines stimulate further cytokine production, particularly IL-6, which is responsible for inducing the acute phase response.

- Cytokine concentrations peak around 24 hours postoperatively and remain elevated for 48-72 hours.

Features of the Acute Phase Response

Fever

Granulocytosis

Production of Acute Phase Proteins in Liver

- CRP

- Fibrinogen

- α2-macroglobulin

Changes in Serum Concentrations of Transport Proteins

- Increase in ceruloplasmin

- Decrease in transferrin, albumin, and α2-macroglobulin

Changes in Serum Concentrations of Divalent Cations

- Copper increases

- Zinc and iron decrease

Minimally Invasive Surgery

- Classical stress responses to abdominal surgery are not greatly altered by reducing surgical trauma, indicating that stimuli arise from visceral and peritoneal afferent nerve fibers in addition to the abdominal wall.

- Anesthesia has little effect on the cytokine response to surgery because it cannot influence tissue trauma. Although regional anesthesia inhibits the stress response to surgery, it does not significantly affect cytokine production.

The Effect of Anesthesia on the Stress Response to Surgery

Opioids

- Suppress hypothalamic and pituitary hormone secretion.

- Large doses of morphine (4 mg/kg) block growth hormone and inhibit cortisol release until the onset of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Fentanyl (50-100 µg/kg), sufentanil (20 µg/kg), and alfentanil (1.4 µg/kg) suppress pituitary hormone secretion until CPB.

- Fentanyl 15 µg/kg inhibits cortisol and glucose responses to lower abdominal surgery.

Benzodiazepines (BZD)

- Attenuate cortisol responses to peripheral and upper abdominal surgery by inhibiting cortisol production.

Clonidine

- Inhibits stress responses mediated by the sympathetic nervous system.

Epidural Anesthesia

- Prevents endocrine and metabolic responses to surgery by blocking afferent input from the operative site to the CNS, hypothalamic-pituitary axis, and efferent autonomic neuronal pathways to the liver and adrenal medulla, thus abolishing adrenocortical and glycemic responses.

Harmful Effects of Stress Response

- Increased myocardial oxygen demand.

- Splanchnic vasoconstriction (anastomotic breakdown).

- Impaired wound healing (hyperglycemia).

- Sodium and water retention.

- Hypercoagulability (increased risk of VTE).

Innate Immune System

- Pattern recognition molecules on macrophages bind to damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) on damaged or foreign material.

- PRR + DAMPs activate nuclear factor kappa B (NFKB), upregulating transcription of TNF-α and IL-1, leading to:

- Reduced myocardial contractility.

- Leaky endothelium (edema).

- Fever (alters hypothalamic set point).

- Leukocytosis.

- Activation of the clotting pathway, leading to consumption of clotting factors and DIC.

- Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) produces nitric oxide, causing hypotension.

- Intracellular and vascular adhesion molecules (iCAM and iVAM) enable granulocytes to adhere to the endothelium.

Pituitary

- ADH: V1 causes vasoconstriction of the splanchnic bed; V2 causes water retention.

- ACTH: Stimulates cortisol, increasing glucose levels (glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis), fatty acid metabolism, and immunosuppression (inhibits NFKB and leukocytes).

- GH: Limits protein breakdown, promotes lipolysis and glycogenolysis.

- TSH: Risk of fall.

- Prolactin: Has immune-modulating effects.

Sympathetic Activation

- Increases cardiac output (increased contractility and heart rate).

- Vasoconstriction in the skin and splanchnic vessels; vasodilation in skeletal muscle.

- RAAS activation leads to water retention (aldosterone) and splanchnic vasoconstriction (angiotensin II).

Links

References:

- Desborough, J. (2000). The stress response to trauma and surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 85(1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/85.1.109

- Cusack B, Buggy DJ. Anaesthesia, analgesia, and the surgical stress response. BJA Educ. 2020 Sep;20(9):321-328. doi: 10.1016/j.bjae.2020.04.006. Epub 2020 Jul 21. PMID: 33456967; PMCID: PMC7807970.

- Manou‐Stathopoulou, V., Korbonits, M., & Ackland, G. L. (2019). Redefining the perioperative stress response: a narrative review. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 123(5), 570-583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2019.08.011

- Cusack, B. et al.. Anaesthesia, analgesia, and the surgical stress response. BJA Education, Volume 20, Issue 9, 321 – 328

Summaries:

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “3cce8d21-d3c3-4398-869f-7eb9a1f0d67a”