- Scoliosis

- Paediatric Scoliosis

- Links

{}

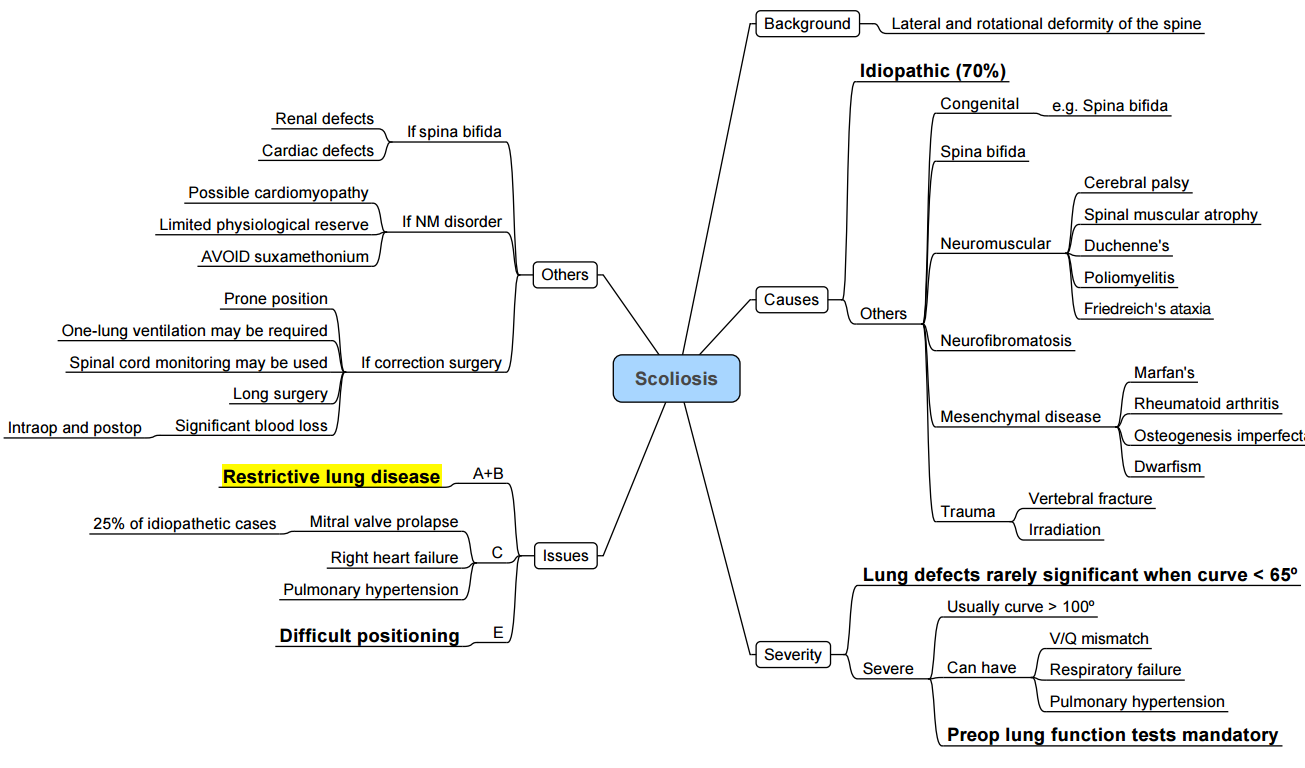

Scoliosis

Introduction

Definition

- Scoliosis is a three-dimensional deformity of the vertebral column characterised by a lateral curvature ≥ 10° measured by the Cobb method on an upright postero-anterior radiograph, usually accompanied by vertebral rotation.

- Kyphoscoliosis denotes combined coronal and sagittal deformity and confers greater pulmonary compromise.

Epidemiology & Natural History

- Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) accounts for ~80 % of cases and has a female predominance (≈3:1). Curve progression risk increases with growth potential (Risser < 2, open triradiate cartilage) and Cobb angle > 30°.

- Early-onset scoliosis (< 10 yr) carries a higher incidence of restrictive lung disease and pulmonary hypertension in adulthood.

Aetiology & Classification

| Category | Examples | Key Anaesthetic Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic • Infantile (< 3 yr) • Juvenile (3–10 yr) • Adolescent (10 yr–skeletal maturity) |

Usually otherwise healthy | Large blood loss, difficult positioning |

| Neuromuscular | Cerebral palsy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), spinal muscular atrophy | Aspiration risk, cardiomyopathy (DMD), severe restrictive lung disease |

| Congenital | Hemivertebrae, failure of segmentation, spinal dysraphism | Associated renal & cardiac anomalies, difficult airway |

| Syndromic | Marfan syndrome, neurofibromatosis, osteogenesis imperfecta | Aortopathy, dural ectasia, brittle bones |

| Degenerative (adult) | Osteoarthritis, osteoporosis | Elderly physiology, anticoagulation |

| Other | Post-traumatic, infective (TB), neoplastic | Sepsis optimisation, metastatic disease |

Indications for Surgical Correction

- Progressive thoracic curve > 50 ° or lumbar curve > 40 ° despite bracing.

- Significant coronal or sagittal imbalance causing pain or cardiopulmonary impairment.

- Rapid progression (> 10 ° yr⁻¹) in skeletally immature patients.

Anaesthetic Challenges in Major Spinal Fusion

| Domain | Key Considerations |

|---|---|

| Respiratory | Restrictive pattern (↓FVC, ↓FEV₁). Cobb > 60 ° predicts impaired gas transfer; Cobb > 80 ° → nocturnal hypoventilation; Cobb > 100 ° → chronic hypercapnia & pulmonary hypertension. |

| Cardiovascular | Mitral valve prolapse (AIS), dilated cardiomyopathy (DMD), systemic hypertension (NF1). Echo ± cardiology review if symptomatic or neuromuscular disease. |

| Airway | Difficult intubation with cervical/thoracic curves; pre-op imaging if atlanto-axial instability suspected. |

| Positioning (prone) | Pressure injury, ocular perfusion (POVL), venous air embolism (VAE); use Jackson or Wilson frame to avoid abdominal compression. |

| Blood Loss | Multilevel osteotomies & muscle dissection → average 20–80 mL kg⁻¹; multimodal blood-conservation (high-dose tranexamic acid, cell salvage, controlled hypotension). |

| Neuro-monitoring | Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) & transcranial motor evoked potentials (tcMEP); avoid long-acting neuromuscular blockers, maintain MAP ≥ 70 mmHg during instrumentation. |

| Pain & ERAS | Severe early nociceptive pain plus neuropathic component; multimodal opioid-sparing regimen improves mobilisation and length of stay. |

Pre-operative Assessment & Optimisation

History & Examination

- Exercise tolerance, orthopnoea, sleep-disordered breathing.

- Document baseline neuro-status and functional handgrip (wake-up test ability).

- Screen for difficult airway and syndromic features.

Investigations (minimum)

| Test | Thresholds warranting further work-up |

|---|---|

| Spirometry (FEV₁ & FVC) | FVC < 50 % predicted → anaesthesia + respiratory review |

| Chest radiograph | Measure Cobb; Cobb > 60 ° → arterial blood gas (ABG) & full pulmonary function tests (PFTs) |

| ABG | PaCO₂ > 45 mmHg → plan postoperative ventilation/ICU |

| Echocardiogram | All neuromuscular scoliosis or clinical signs of cardiomyopathy/pulmonary hypertension |

| Laboratory | FBC, coagulation, renal profile, type & screen (2 units on standby) |

Optimisation

- Respiratory: Treat infections; bronchodilators for reversible obstruction; nightly non-invasive ventilation (if chronic hypercapnia); chest physiotherapy & incentive spirometry.

- Cardiac: Optimise heart failure, beta-blockade or ACE-is; cardiology review for DMD.

- Nutrition: Aim albumin > 30 g L⁻¹; high-protein supplements.

- Haematology: Treat iron-deficiency; consider erythropoietin for Hb < 12 g dL⁻¹.

- Counselling: Explain neuro-monitoring, potential need for staged surgery, postoperative ventilation and analgesia plan.

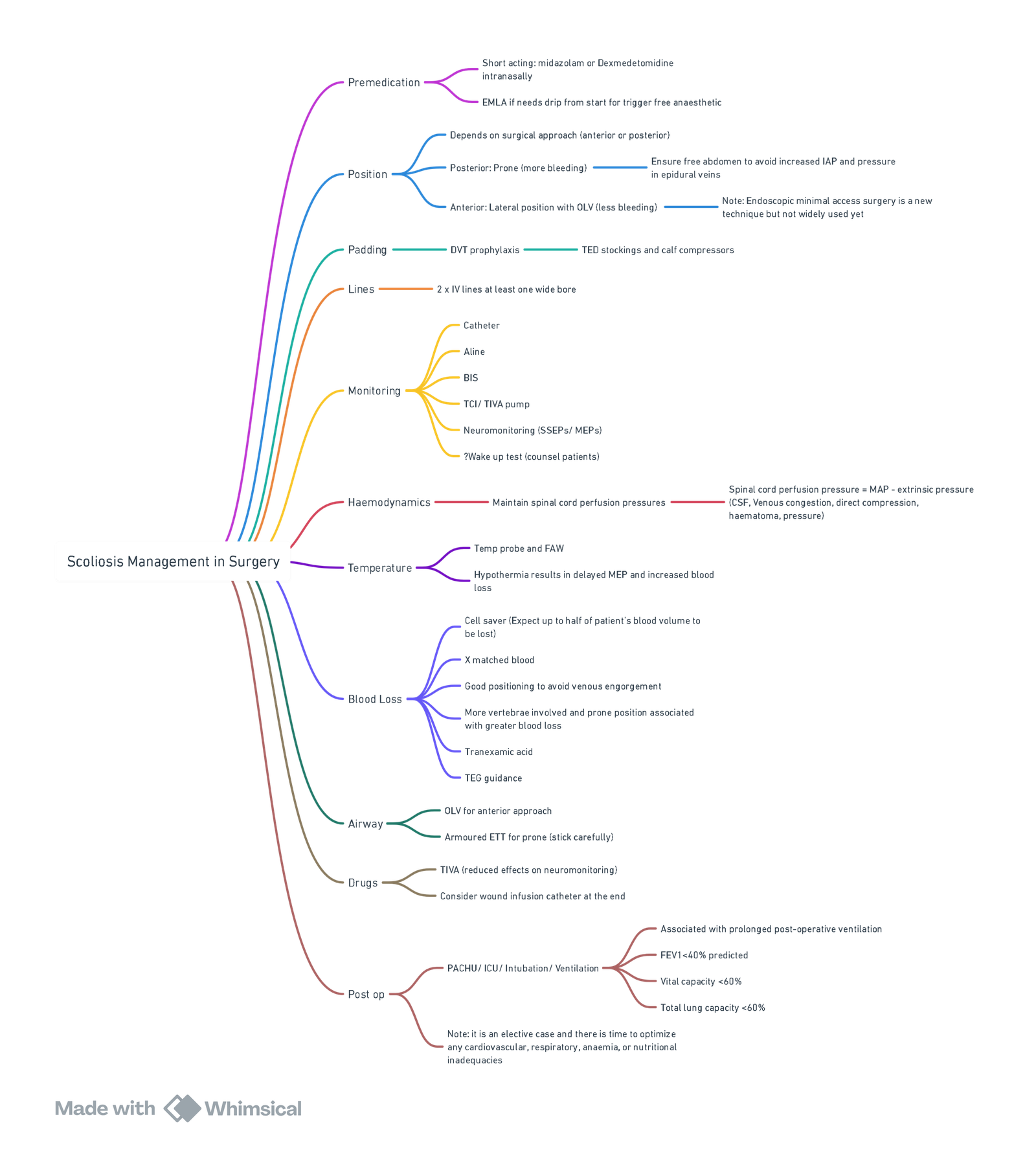

Intra-operative Management

Monitoring & Access

- Standard ASA monitors + invasive arterial pressure, large-bore peripheral IV × 2, ± central line if anticipated > 1 blood volume loss.

- Bispectral index (BIS) or processed EEG to titrate total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA).

- Cell salvage with leucocyte filter; antifibrinolytic infusion

Anaesthetic Technique

| Aspect | Current Evidence-based Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Induction | Propofol (2–3 mg kg⁻¹) ± short-acting opioid; single intubating dose of rocuronium (0.6 mg kg⁻¹) is acceptable—reverse with sugammadex before baseline tcMEP; alternatives: no relaxant if difficult airway predicted. |

| Maintenance | TIVA (propofol 100-150 μg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹ + remifentanil 0.1–0.3 μg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹) minimises tcMEP suppression; inhalational ≤ 0.5 MAC with propofol infusion is acceptable. Dexmedetomidine 0.3–0.7 μg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ reduces propofol dose and opioid requirements without clinically significant SEP changes. |

| Blood-sparing | Tranexamic acid 30 mg kg⁻¹ loading over 15 min, then 10 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (high-dose 100 mg kg⁻¹ + 10 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ yields greatest reduction but uncertain safety—reserve for high-risk cases). |

| Controlled Hypotension | Target MAP 65–70 mmHg during exposure; raise to ≥ 70 mmHg for instrumentation/osteotomy and ≥ 80 mmHg for neuro-deficit or spinal cord injury. |

| Fluids | Balanced crystalloid 3–4 mL kg⁻¹ h⁻¹; albumin or viscoelastic-guided coagulation products to maintain ROTEM target values. |

| Temperature | Forced-air warming, fluid warmers; core T° > 36 °C to preserve evoked potentials. |

Positioning (Prone)

- Eyes free of pressure, head neutral, abdomen off table to limit venous engorgement.

- Padding of chest, iliac crests, knees and elbows; frequent checks after repositioning.

- Document eyes checks hourly to mitigate postoperative visual loss.

Neuro-monitoring Response Algorithm

| Event | Immediate Actions |

|---|---|

| tcMEP/SSEP amplitude ↓ > 50 % | ↑ MAP to ≥ 85 mmHg; normalise Hb & oxygenation; check anaesthetic depth; exclude mechanical causes (distraction rod, hypotension, hypothermia); consider wake-up test. |

Post-operative Care

Immediate (0–24 h)

- Extubate in theatre or ICU depending on lung function, blood loss and neuromuscular disease.

- Haemodynamic goals: MAP ≥ 70 mmHg (≥ 80 mmHg if intra-operative cord compromise).

- Neuro-checks: motor power & sensation q30 min (6 h) → q1 h (24 h).

- Analgesia: multimodal regimen

- Ketamine 0.25 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (24 h)

- Dexmedetomidine 0.3–0.5 μg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (sedation score ≤ -2)

- Acetaminophen 15 mg kg⁻¹ 6-hourly

- Reduced-dose opioid PCA (morphine 0.02 mg kg⁻¹ demand, lock-out 8 min)

- Erector spinae plane block (ESPB) with 0.375 % ropivacaine 20 mL side⁻¹ lowers early NRS and morphine use.

- VTE prophylaxis: intermittent pneumatic compression intra-op → LMWH 12–24 h post-op once haemostasis secured; continue until full ambulation.

Ongoing (Day 1–3)

- Transition to oral multimodal analgesia (paracetamol, tramadol/controlled-release oxycodone ± NSAID if surgeon agrees).

- Physiotherapy: sit-to-stand on Day 1, ambulation Day 2.

- Monitor ileus, urinary retention, wound drainage, SIADH (in neuromuscular disease).

Complications & Prevention

| Complication | Prevention & Early Detection |

|---|---|

| Massive blood loss | High-dose TXA, cell salvage, viscoelastic-guided transfusion |

| Hypothermia | Active warming, warmed fluids |

| POVL | Padding, keep head neutral, limit anaemia/hypotension |

| VTE | Early mobilisation, mechanical + LMWH prophylaxis |

| Airway oedema | Judicious fluids, leak test before extubation |

| Neurological injury | Continuous SSEP/tcMEP, maintain perfusion, prompt wake-up test |

| Chronic pain | Intra-operative ketamine & dexmedetomidine, ESPB, early physiotherapy |

Analgesic Techniques Summary

| Technique | Evidence & Caveats |

|---|---|

| ESPB | RCTs show ↓ opioid by ~30 % first 24 h; safe when performed pre-incision. |

| Intrathecal Morphine (3-5 μg kg⁻¹) | Excellent analgesia but respiratory monitoring ≥ 24 h. |

| Wound catheters | Simple; infection risk minimal with ≤ 48 h dwell. |

| Dexmedetomidine infusion | Useful adjunct but prolongs sedation at doses > 0.7 μg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹. |

| Ketamine infusion | Superior to dexmedetomidine for opioid-sparing; avoid in psychosis. |

| NSAIDs | Controversial effect on fusion; short-course ketorolac (≤ 72 h) appears safe. |

Risk-mitigation Checklist

- Two cross-matched units immediately available.

- TXA drawn-up before knife-to-skin.

- Neuromonitoring baseline established before instrumentation.

- Eye checks & pressure points logged hourly.

- Wake-up test protocol printed and available.

- Post-op ICU bed confirmed.

- Multidisciplinary huddle (surgeon, anaesthetist, neuro-physiologist, nursing) before induction.

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Paediatric Scoliosis

Anaesthetic Concerns

(a) Respiratory

- Progressive restrictive pattern → ↓ forced vital capacity (FVC) & total lung capacity.

- FVC < 40 % predicted or Cobb > 90 ° strongly predicts need for postoperative ventilation.

- Spine surgery may transiently reduce PFTs by up to 60 % with recovery over 1–2 months.

- ↓ Chest-wall compliance, V/Q mismatch → chronic hypoxaemia.

- Hypercapnia (PaCO₂ > 45 mmHg) indicates advanced disease and correlates with pulmonary hypertension (PH).

(b) Cardiovascular

- Chronic hypoxia ± sleep-disordered breathing → PH → right-ventricular hypertrophy/failure.

- Up to 30 % of idiopathic cases have valvular abnormalities; congenital heart disease incidence ≈ 4 %. Cardiac lesions are more common in males and thoracolumbar curves.

Common Problems

| Domain | Key Points | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | FVC & VC fall with curve severity; FVC < 40 % predicted → high likelihood of postoperative ventilation; lung volumes may fall another 40 % immediately post-fusion and normalise over 2 months. | Plan elective ICU, consider postoperative non-invasive ventilation; pre-op airway clearance. |

| Cardiovascular | ↑ pulmonary vascular resistance independent of curve size; vigilance for valvular lesions & congenital heart disease | Baseline ECG & echo; optimise PH/treat heart failure. |

| Neurological | Baseline deficits variable; risk of cord injury during correction. | Document exam; consent for wake-up test. |

| Neuromuscular aetiology | DMD & other myopathies → cardiomyopathy, respiratory weakness, anaesthesia-induced rhabdomyolysis (AIR) | Avoid succinylcholine & volatile agents; use TIVA; anticipate prolonged ventilation. |

| Nutrition | Chronic illness ± rapid growth may cause malnutrition. | Pre-op dietetic input; albumin > 30 g L⁻¹. |

Peri-operative Issues & Strategies

| Phase | Key Actions |

|---|---|

| Pre-operative | • Full cardiorespiratory work-up (PFT, ABG if Cobb > 60 ° or FVC < 50 %). • Echo for all neuromuscular curves or murmurs. • Optimise respiratory muscle training, treat infections, initiate nocturnal BiPAP if chronic hypercapnia. • Bloods: FBC, coagulation, group & screen (≥ 2 units ready). |

| Induction & Maintenance | • TIVA (propofol–remifentanil) ± adjunct dexmedetomidine 0.3–0.6 µg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ preserves SEP/MEP. • One intubating dose of rocuronium acceptable; reverse with sugammadex before baseline tcMEP. • Neuromuscular disease: omit muscle relaxant, avoid volatile agents & succinylcholine (AIR risk). |

| Position (prone) | Jackson/Wilson frame; free abdomen; eye checks hourly. |

| Spinal cord protection | Continuous SSEP/tcMEP; maintain MAP ≥ 70 mmHg (≥ 80 mmHg if signal loss). |

| Blood conservation | TXA 30 mg kg⁻¹ load → 10 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ infusion; cell salvage. |

| Analgesia | Multimodal regimen (see ERAS protocol); ESPB reduces 24-h opioid by ≈ 30 %. |

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital Pain Protocol

- The protocol below integrates recent RCT data on ketamine, gabapentin and ESPB to optimise opioid-sparing while maintaining compatibility with neuro-monitoring.

Pre-operative

| Team | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Orthopaedic | Gabapentin 15 mg kg⁻¹ PO night before & morning of surgery, then 8-hourly (target 10 mg kg⁻¹ q8 h). Pre-/post-fusion gabapentin halves early opioid use and pain scores. |

| Anaesthesia | Counsel patient/family; assess PCA suitability; provide information sheet. |

Intra-operative

| Step | Drug & Dose |

|---|---|

| Loading analgesics | Paracetamol 20 mg kg⁻¹ IV; morphine 0.1–0.2 mg kg⁻¹ IV (after baseline MEP). |

| Adjuvants (post-monitoring) | Ketamine infusion 0.25–0.35 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (supported by 2022 meta-analysis showing 25 % opioid reduction). Clonidine 1–2 µg kg⁻¹ IV or switch to dexmedetomidine 0.3–0.6 µg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹. |

| Regional | Bilateral ultrasound-guided ESPB before closure: bupivacaine 3 mg kg⁻¹ total (0.5 mL kg⁻¹ side⁻¹) + clonidine 1 µg kg⁻¹. |

| PONV prophylaxis | Dexamethasone 0.15 mg kg⁻¹ IV + ondansetron 0.15 mg kg⁻¹ IV. |

Post-operative (ICU Day 0)

| Medication | Schedule |

|---|---|

| Paracetamol | 15 mg kg⁻¹ IV q6 h. |

| Clonidine | 1–3 µg kg⁻¹ PO q8 h or dexmedetomidine 0.3–0.5 µg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ (avoid Ramsay > 4). |

| Gabapentin | Continue 3–5 mg kg⁻¹ PO q8 h → titrate to target 10 mg kg⁻¹ q8 h. |

| Ketamine | 0.25–0.35 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ for 24 h, then wean. |

| Morphine | PCA: background 0–0.5 mL h⁻¹; bolus 20 µg kg⁻¹; lock-out 5 min. |

| PONV | Ondansetron 0.15 mg kg⁻¹ IV q8 h. |

| Others | Lactulose 0.5 mL kg⁻¹ PO q12 h; early physiotherapy & caregiver distraction techniques. |

Ward Days 1–3

- Pain service: taper PCA, introduce ibuprofen 10 mg kg⁻¹ q8 h once haemostasis & renal function normal.

- Physiotherapy: edge-of-bed mobilisation Day 1; standing & walking Day 2 (coordinate timing with oral analgesic dosing)

Discharge (≈ Day 3–5)

| Drug | Dose & Duration |

|---|---|

| Paracetamol | 15 mg kg⁻¹ PO q6 h. |

| Ibuprofen | 10 mg kg⁻¹ PO q8 h. |

| Gabapentin | 10 mg kg⁻¹ PO q8 h × 2 weeks, then taper. |

| Tramadol (prn) | 1–2 mg kg⁻¹ PO q6 h. |

Key Points for Muscular Dystrophy

- Avoid succinylcholine and minimise/omit volatile agents–high risk of AIR with hyperkalaemic arrest.

- Use non-depolarising relaxants titrated to nerve stimulator; reverse with sugammadex 2 mg kg⁻¹.

- Post-operative ventilation likely when FVC < 40 % predicted or cardiomyopathy present; plan elective ICU.

Links

References:

- Hudec J, Prokopová T, Kosinová M, Gál R. Anesthesia and Perioperative Management for Surgical Correction of Neuromuscular Scoliosis in Children: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2023 May 24;12(11):3651. doi: 10.3390/jcm12113651. PMID: 37297846; PMCID: PMC10253354.

- Fung, A. and Wong, P. C. (2023). Anaesthesia for scoliosis surgery. Anaesthesia &Amp; Intensive Care Medicine, 24(12), 744-750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2023.09.004

- Anaesthetic Guideline for Posterior Approach to Scoliosis Corrective Surgery. UCT guideline

- Young, C. D., McLuckie, D., & Spencer, A. O. (2019). Anaesthetic care for surgical management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. BJA Education, 19(7), 232-237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2019.03.005

- Young CD, McLuckie D, Spencer AO. Anaesthetic care for surgical management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. BJA Education. 2019;19(7):232-237. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Hudec J, Prokopová T, Kosinová M, Gál R. Anesthesia and perioperative management for surgical correction of neuromuscular scoliosis in children: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(11):3651. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Li X et al. The optimal dose of intravenous tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss in multilevel spine surgery: a network meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26:8233. bmcmusculoskeletdisord.biomedcentral.com

- Madani S et al. Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid in spinal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus. 2025;17:e11165496. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Xu H et al. Effects of dexmedetomidine on evoked potentials in spine surgery: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023;23:1990. bmcanesthesiol.biomedcentral.com

- Wang Y et al. Bilateral ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block improves postoperative analgesia after posterior spinal fusion in paediatric idiopathic scoliosis: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2024;41:123-131. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Wong A et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in elective spine surgery: a narrative review. Global Spine J. 2021;11(8):1214-1223. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- Yuan N, et al. Spinal fusion pulmonary management pathway. Johns Hopkins Medicine; 2023. hopkinsmedicine.org

- Elsamadicy N, et al. Postoperative pulmonary complications in complex paediatric spine surgery. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Anderson DE, et al. Multimodal pain control with gabapentin in adolescent posterior spinal fusion: RCT. Spine Deform. 2020;8:177-185. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Mariscal G, et al. Ketamine for postoperative pain in AIS: meta-analysis. Eur Spine J. 2022;31:3492-3499. pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Gao J, et al. Bilateral ESPB for paediatric posterior fusion: RCT protocol. Trials. 2024;25:498. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- Yang X, et al. Cardiac abnormalities in idiopathic scoliosis: risk-factor analysis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:16013. nature.com

- van den Bersselaar L, et al. Anaesthetic management in neuromuscular disease. Front Anesthesiol. 2023. pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Summaries:

Paediatric scoliosis

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “54f8b1be-f289-4c8a-a70d-9d2f1e0af0ab”