- Infective Endocarditis (IE)

- Prophylaxis

- Anaesthesia for Infective Endocarditis (IE) Surgery

- Links

{}

Infective Endocarditis (IE)

Introduction

- IE is a microbial infection of native or prosthetic heart valves or the endocardial surface.

- Incidence: 3–15 per 100,000 annually (1.7–7.2 in some cohorts).

- Mortality: ~20% in-hospital; ~30% at one year.

- Risk factors vary by geography:

- Developing countries: Rheumatic heart disease.

- Developed countries: Congenital/degenerative valve disease, prosthetic valves, implantable cardiac devices.

- Non-cardiac: IVDU, indwelling catheters, immunocompromised states, malignancy.

- Median age: 47–69 years.

- Sex ratio: Female:Male = 1:2.

Definition

- IE is a multisystem disorder caused by microbial infection (usually bacterial) of heart valves or mural endocardium.

- Results in tissue destruction and formation of vegetations.

Aetiology

Causative Agents

- Staphylococcus aureus: 31–54%; most common overall.

- Coagulase-negative Staphylococci: Major cause of prosthetic valve IE.

- Streptococci (oral): Less common than S. aureus.

- HACEK organism

- Fungi (Candida, Aspergillus): Seen in IVDU, prosthetic valves, long-term central venous catheters.

Pathogenesis

Acute Endocarditis

- Predisposing factors: Pre-existing valve disease, poor dentition/dental procedures, IVDU, invasive procedures.

- Mechanism:

- Turbulent flow damages endothelium

- Sterile thrombus forms → bacterial adherence during bacteremia.

Infective Endocarditis

- Infection of thrombus → vegetation.

- Colonization occurs mostly on abnormal valves.

- Immune response:

- Symptoms: Fever, malaise, chills.

- Positive blood cultures.

- Immune complex deposition → organ damage.

Pathophysiology Summary

- Endothelial damage → Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis.

- Bacteremia → Microbial adherence to thrombus.

- Vegetation formation: Fibrin + platelets.

- Biofilm production → Valve destruction, emboli, abscesses.

Complications

- Valvular damage: Most common in mitral > aortic > tricuspid valves.

- Leads to regurgitation or obstruction.

- Vegetations: Visualized on echo; cause emboli.

- Immune complex deposition:

- Glomerulonephritis (kidney).

- Vasculitis (e.g., Roth’s spots).

- Septic emboli:

- Large emboli → organ infarcts (brain, spleen).

- Small emboli → peripheral infarcts (fingers/toes).

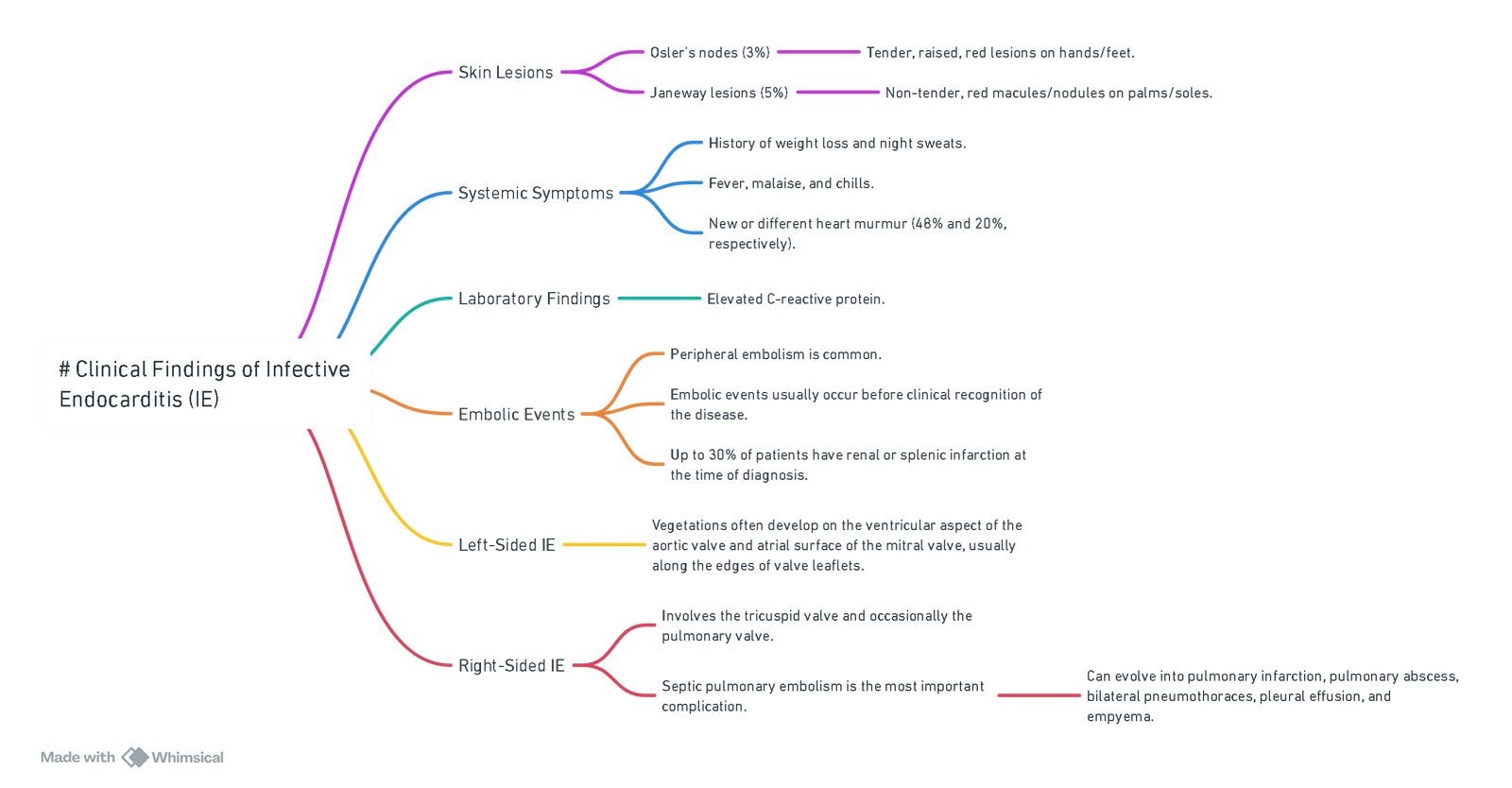

Clinical Findings

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Diagnosis

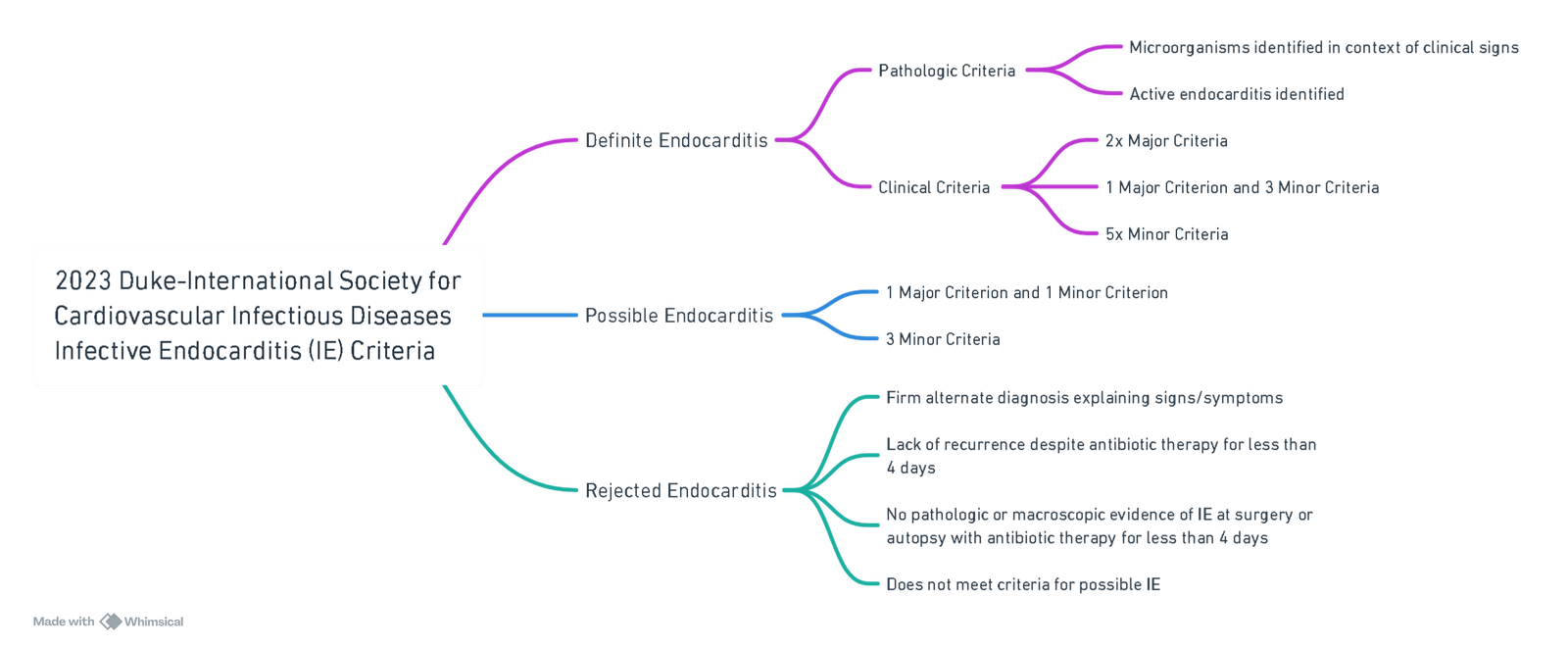

2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Infective Endocarditis (IE) Criteria

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

I. Major Criteria

A. Microbiologic

- ≥2 positive cultures with typical IE organisms (e.g., S. aureus, viridans streptococci).

- ≥3 cultures with non-typical organisms.

- Positive PCR or sequencing (e.g., for Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella spp., T. whipplei).

- Serology (e.g., C. burnetii IgG >1:800, IFA for Bartonella spp. IgG ≥1:800).

B. Imaging

- Echocardiography or cardiac CT:

- Vegetation, perforation, aneurysm, abscess, pseudoaneurysm, fistula.

- New prosthetic valve dehiscence.

- New valvular regurgitation (not just worsening).

- 18F-FDG PET/CT:

- Abnormal uptake on valve, graft, or device (≤3 months post-implantation).

C. Surgical

- Direct visualization of vegetations or abscess during surgery, even if imaging negative.

II. Minor Criteria

- Predisposition: Previous IE, prosthetic valve, valve repair, CHD, CIED, severe valve disease, IVDU, TAVI.

- Fever: >38°C.

- Vascular phenomena: Emboli, infarcts (cerebral, splenic), mycotic aneurysms, Janeway lesions, conjunctival hemorrhages.

- Immunologic phenomena: Glomerulonephritis, Osler nodes, Roth spots, rheumatoid factor.

- Microbiologic evidence not meeting major criteria.

- Imaging minor: PET/CT findings within 3 months post-surgery.

- Physical exam: New murmur when echo unavailable.

Echocardiography

- TTE: Sensitivity 45–60%.

- TOE: Sensitivity 90–100%.

Major Duke Echo Criteria

- Oscillating mass (vegetation).

- Abscess.

- New prosthetic valve dehiscence.

Other Suggestive Echo Findings

- Valve perforation.

- Valve aneurysm.

- Fistula formation.

- Nonspecific valve thickening.

- New regurgitation.

Prognosis: Negative Predictors

Patient-related

- Advanced age, female sex, diabetes, immunosuppression, frailty

Infection-related

- S. aureus, fungal infection, prosthetic valve IE, nosocomial acquisition, multivalve involvement, vegetation >10 mm.

Complications

- Cardiogenic/septic shock.

- Paravalvular complications.

- Stroke, renal failure, persistent bacteremia.

Surgery-related

- Emergency surgery.

- Redo surgery.

- Prolonged bypass/cross-clamp time.

- Re-sternotomy for bleeding.

Risk Assessment

- Multiple IE risk scores available.

- EuroSCORE II most reliable in some centers (local validation essential).

Indications for Urgent Surgery

- Heart Failure:

- Severe regurgitation, obstruction, or intracardiac fistula.

- Uncontrolled Infection:

- Persistent fever or positive cultures despite antibiotics.

- Complications: Abscess, pseudoaneurysm, fistula.

- Prevention of Embolism:

- Vegetation >10 mm with high embolic risk.

Surgical Timing Recommendations

Guidelines

- AHA/ACC: Early surgery during initial hospitalization, even before antibiotics complete

- ESC/JCS: Categorize as emergency (<24h), urgent (few days), elective (post-antibiotics).

- AATS: Early/aggressive surgery, especially for large vegetations.

Evidence

- RCTs, meta-analyses show lower mortality with early surgery.

- Surgery can be delayed in severe stroke/intracranial hemorrhage (≥4 weeks).

IE Post-Stroke and TAVR

- Surgery post-stroke

- Safe if no major neurologic damage.

- Avoid long delays, as outcomes may worsen.

- TAVR-associated IE:

- Surgery may not improve outcomes, particularly after stroke.

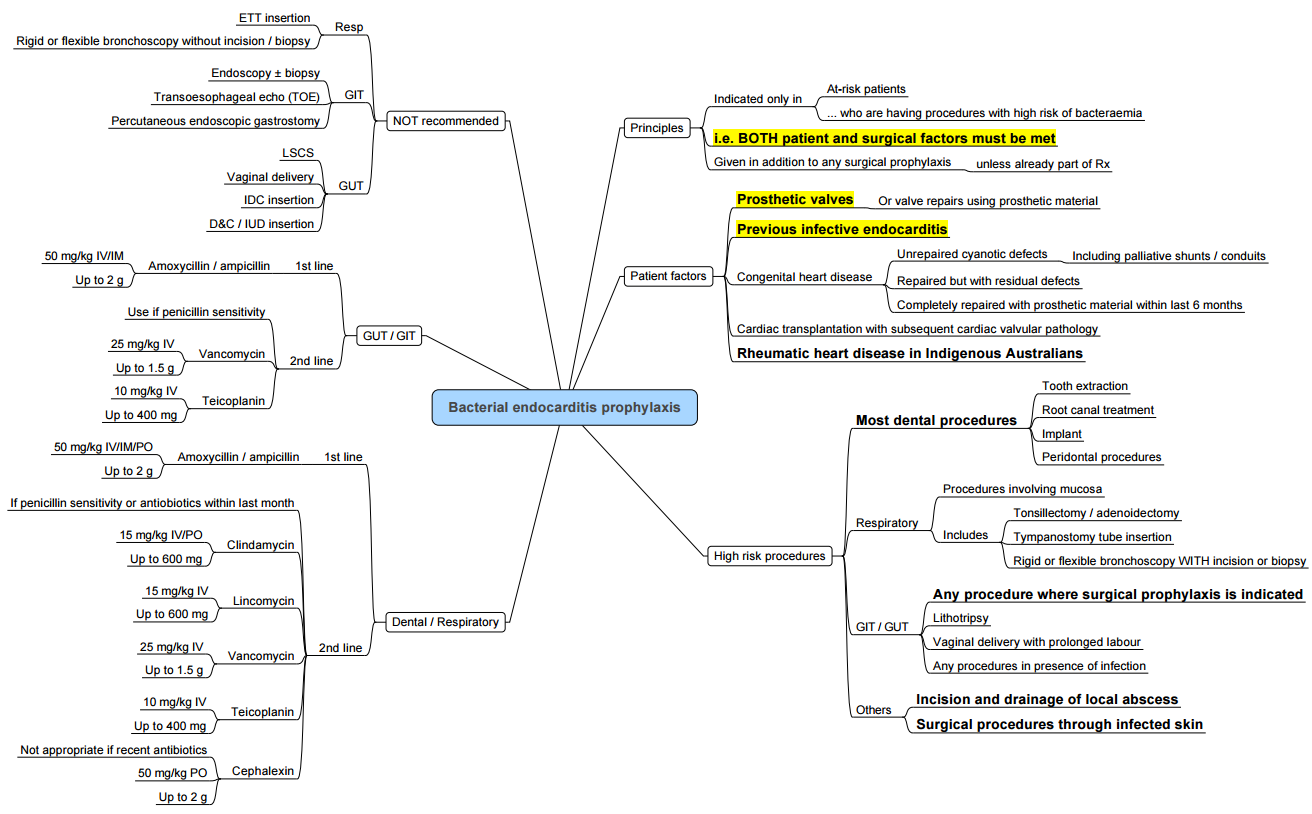

Prophylaxis

- General Consideration:

- Routine prophylaxis is not recommended.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is still recommended in high-risk patients with an actual infection at the operative site (e.g., acquired valvular heart disease, previous valve replacement, or structural congenital heart disease excluding repaired atrial or ventricular septal defect or patent ductus arteriosus).

Groups of Patients Requiring IE Prophylaxis Prior to Surgery

- Prosthetic Cardiac Valve

- History of IE

- Congenital Heart Diseases:

- (i) Cyanotic CHD Unrepaired

- (ii) Cyanotic CHD Repaired within the last 6 months

- (iii) Cardiac transplant recipients with valvular disease

- Cardiac Transplantation with Valvular Heart Disease (VHD)

Surgical Procedures Requiring IE Prophylaxis

- All dental procedures

- Invasive respiratory tract procedures involving incision or biopsy of mucosa

- Procedures involving infected skin

Antibiotic Agents for IE Prophylaxis

- All antibiotics should be administered 30-60 minutes before the procedure.

- Amoxicillin: 2 g PO

- Cannot take orally: Ampicillin 2 g IV/IM

- Allergic to Penicillin:

- Clindamycin 600 mg PO

- Cephalexin 2 g PO

- Allergic to Penicillin and cannot take orally: Clindamycin 600 mg IV

Treatment

- Patients with IE and large vegetations, intracardiac abscess (9-14%), or persisting infection (9-11%) almost always need surgery.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Treatment for the More Frequent Causes of IE

| Clinical Situation | Agent | Dosage and Route | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Prophylaxis | Amoxicillin | 2 g p.o. or i.v. | Single dose |

| B. Prophylaxis (allergic to penicillin) | Clindamycin | 600 mg p.o. or i.v. | Single dose |

| C. Empirical treatment or isolated MSSA | Flucloxacillin | 12 g daily divided into 4–6 doses | 4–6 weeks or ≥6 weeks if prosthetic valve |

| Gentamicin | 3 mg kg-1 divided into 3 doses, i.v. or i.m. | 3–5 days or 2 weeks if prosthetic valve | |

| D. Empirical treatment when risk of MRSA infection, confirmed MRSA or penicillin allergy | Vancomycin | 30 mg kg-1 day-1 divided into 2 doses | 4–6 weeks or ≥6 weeks if prosthetic valve |

| Gentamicin | 3 mg kg-1 divided into 3 doses, i.v. or i.m. | 3–5 days or 2 weeks if prosthetic valve | |

| E. Streptococci and Group D streptococci | Benzylpenicillin | 12–18 million U day-1 i.v., divided into 6 doses | 4 weeks |

Note: For beta-lactam allergic patients, start treatment D without aminoglycoside.

Anaesthesia for Infective Endocarditis (IE) Surgery

Pre-operative Priorities

| Domain | Key tasks |

|---|---|

| Haemodynamic assessment | Identify lesion-specific goals (Table 1). Document ventricular function by TOE/TTE; quantify pulmonary artery pressures; screen for septic cardiomyopathy. |

| Neurology | Brain MRI/CT for stroke, haemorrhage, or mycotic aneurysm. 2023 ESC guidance permits early surgery (≤72 h) after ischaemic stroke if indicated; defer ≥4 weeks after intracranial haemorrhage unless life-saving. |

| Embolic focus | Full‐body CT to detect splenic, renal or lung abscesses. Drain splenic abscess electively before cardiac surgery when feasible. |

| Microbiology | ≥3 blood-culture sets before antibiotics; continue tailored IV antibiotics until sternotomy. Check recent aminoglycoside/vancomycin levels. |

| Coagulation profile | Baseline ROTEM/TEG, antithrombin (AT) activity and platelet count; anticipate heparin resistance. |

| Device removal | Remove infected cardiac implantable electronic devices during the same anaesthetic. |

| Informed consent | Discuss stroke, bleeding, renal failure, prolonged ventilation and need for mechanical circulatory support (MCS). |

Haemodynamic Goals for Common IE-related Lesions

| Lesion/physiology | HR | Contractility | Pre-load | After-load | Anaesthetic notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic regurgitation | 80–100 min⁻¹ | Mild ↑ | Moderate ↑ | ↓ | Avoid bradycardia; IABP contraindicated |

| Aortic stenosis | 60–70 min⁻¹ (sinus) | Maintain | High | Maintain | Slow induction, treat hypotension rapidly |

| Mitral regurgitation | 80–100 min⁻¹ | ↑ | Moderate ↑ | ↓ | Prevent ↑PVR (hypoxia, hypercarbia) |

| Mitral stenosis | 50–65 min⁻¹ (sinus) | Preserve | High | Maintain | ß-block tachycardia; avoid fluid overload |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 80–100 min⁻¹ | ↑ | High | ↓/n | Low threshold for inhaled NO or milrinone |

| Septic cardio-myopathy | 80–95 min⁻¹ | ↑ (dobutamine/milrinone) | Moderate ↑ | Titrate NE/vasopressin | Consider early MCS (Impella®, ECMO) |

Intra-operative Management

Monitoring & Access

- TOE mandatory for de-airing, vegetation localisation and immediate prosthetic assessment.

- Large-bore arterial line ± PiCCO; right-heart pressures via Swan-Ganz if severe pulmonary hypertension.

- Two wide-bore peripheral IVs plus at least one upper-body central line; cerebral near-infra-red spectroscopy (NIRS) for high embolic load.

Induction & Maintenance

| Problem | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Full stomach / haemodynamic lability | RSI with etomidate ± ketamine; maintain SVR with phenylephrine/NE bolus. |

| Sepsis / vasoplegia | Avoid high volatile concentrations; balanced anaesthesia (opioid-benzodiazepine-low MAC volatile) or TIVA; prepare vasopressin 0.03 U min⁻¹ and methylene blue 1.5 mg kg⁻¹. |

| Pulmonary hypertension | FiO₂ 1.0, normocapnia, inhaled prostacyclin or NO ready. |

Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) Considerations

- Heparin resistance is common (AT activity <70 %; high fibrinogen). Dose 400 IU kg⁻¹ initially; if ACT < 480 s repeat heparin, give AT concentrate 30–50 IU kg⁻¹ or FFP 10 mL kg⁻¹.

- Bivalirudin is a validated alternative when HR persists or HIT suspected.

- Treat systemic inflammatory response: ultrafiltration, leucocyte filters, cytokine haemoadsorption (CytoSorb®) during CPB in high-risk S. aureus IE–early data show improved haemodynamics without excess bleeding; still investigational.

- Tranexamic acid 30 mg kg⁻¹ load then 15 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ reduces blood loss; watch for convulsions in renal impairment.

- Aim for moderate hypothermia (32 °C) and low alpha-stat pCO₂ management; avoid deep hypothermic circulatory arrest unless essential for root/arch abscess.

Valve & Abscess Surgery

- Extensive debridement may require root or intervalvular fibrosa reconstruction; anticipate prolonged CPB/aortic cross-clamp times and transfusion.

- For large mobile vegetations with cerebral infarct <72 h, proceed urgently; defer if major haemorrhage.

Separation from CPB

- Restore normothermia, Hb >8 g dL⁻¹ (10 g dL⁻¹ if coronary disease).

- High likelihood of vasoplegia: start NE 0.05–0.1 µg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹ before unclamp; add vasopressin early.

- Low CO syndrome: incremental dobutamine 2.5–10 µg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹ or milrinone 0.25–0.5 µg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹; wean volatile to ≤0.5 MAC; consider levosimendan loading if EF < 35 %.

- ECMO/Impella rapidly for refractory failure or uncontrollable bleeding.

Haemostasis & Transfusion

| Issue | Principle |

|---|---|

| Baseline anaemia | Optimise pre-op Hb with IV iron/erythropoietin where surgery can be delayed (>7 d). |

| Platelet consumption & antibiotic effects | Repeat platelet count after induction; transfuse if <100 × 10⁹ L⁻¹ and bleeding. |

| Point-of-care guided therapy | Use ROTEM/TEG algorithms: give fibrinogen concentrate if FIBTEM A10 ≤ 8 mm post-protamine. IE patients often start with high fibrinogen so replacement rarely required. |

| Prothrombotic tendency | Restart prophylactic anticoagulation within 12–24 h if surgical bleeding controlled; early aspirin for prosthetic valve/ascending graft. |

Post-operative Management

- Ventilation & sedation: Lung-protective ventilation; analgesia plus light propofol/dexmedetomidine infusion; daily neurological review.

- Antibiotics: Continue pathogen-directed regimen; monitor serum levels (especially aminoglycoside/vancomycin) due to altered Vd after CPB.

- Renal support: Early CRRT for AKI/oliguria; adjust antibiotic dosing.

- Neurological events: CT/MRI if new deficit; mechanical thrombectomy for large‐vessel occlusion within 24 h; no thrombolysis.

- Conduction disturbance: Continuous telemetry; anticipate AV-block with perivalvular abscess—epicardial pacing wires and pacing box ready; ≥ second-degree block persisting > 7 days → permanent pacemaker

- Secondary prevention: Oral hygiene counselling, antibiotic prophylaxis (dental, invasive airway/GI/genitourinary procedures), lifestyle advice.

Follow-up

- Lifelong cardiology review with 6and 12-month TOE, then yearly.

- Education on fever surveillance; low threshold for blood cultures.

- Early resumption/continuation of high-intensity statin, ß-blocker and RAAS inhibitor unless contraindicated.

Links

References:

- Martínez, G. and Valchanov, K. (2012). Infective endocarditis. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care &Amp; Pain, 12(3), 134-139. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mks005Fowler, V. G., Durack, D. T., Selton‐Suty, C., Athan, E., Bayer, A. S., Chamis, A. L., … & Miró, J. M. (2023).

- Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3391-3493. https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Endocarditis-Guidelines

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. 2023 AHA Scientific Statement on infective endocarditis in adults. Circulation. 2023;148:e377-e496.

- Mariscalco G, Raffa GM, Fiore A, et al. Timing of surgery after stroke in infective endocarditis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;118:449-459.

- Greco T, Landoni G, Dell’Acqua A, et al. Tranexamic acid in cardiac surgery: an updated meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2023;131:113-124.

- Sörelius K, Ivert T, Scherman J, et al. Infective endocarditis is a risk factor for heparin resistance during cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:3625-3632.

- Koster A, Sokolovic M, van Hagen M, et al. CytoSorb haemoadsorption in infective endocarditis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Perfusion. 2024;39:7-18.

- Fedoruk L, Camacho C, El Hassan M, et al. Antithrombin concentrate vs FFP for heparin resistance in IE surgery: propensity analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;20:112.

- Stop-or-Not Trial Investigators. Continuation vs discontinuation of RAAS inhibitors before major surgery. JAMA. 2024;332:1121-1131.

- The 2023 duke-international society for cardiovascular infectious diseases criteria for infective endocarditis: updating the modified duke criteria. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 77(4), 518-526. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad271

- Hermanns H, Eberl S, Terwindt LE, Mastenbroek TCB, Bauer WO, van der Vaart TW, Preckel B. Anesthesia Considerations in Infective Endocarditis. Anesthesiology. 2022 Apr 1;136(4):633-656. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004130. PMID: 35120196.

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries

IE prophylaxis

Calgary_IE

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “7b2834ab-d5c1-424d-b4c3-42f2928b93e6”