{}

Acute & Chronic Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

Pathophysiology

Primary Injury

- Mechanical insult–traction, compression, shear or laceration destroys grey/white-matter tracts.

Secondary Injury (minimise intra-theatre)

- Within minutes–weeks: spinal cord ischaemia, glutamate excitotoxicity, inflammatory cytokine surge, oedema, free-radical formation and delayed apoptosis

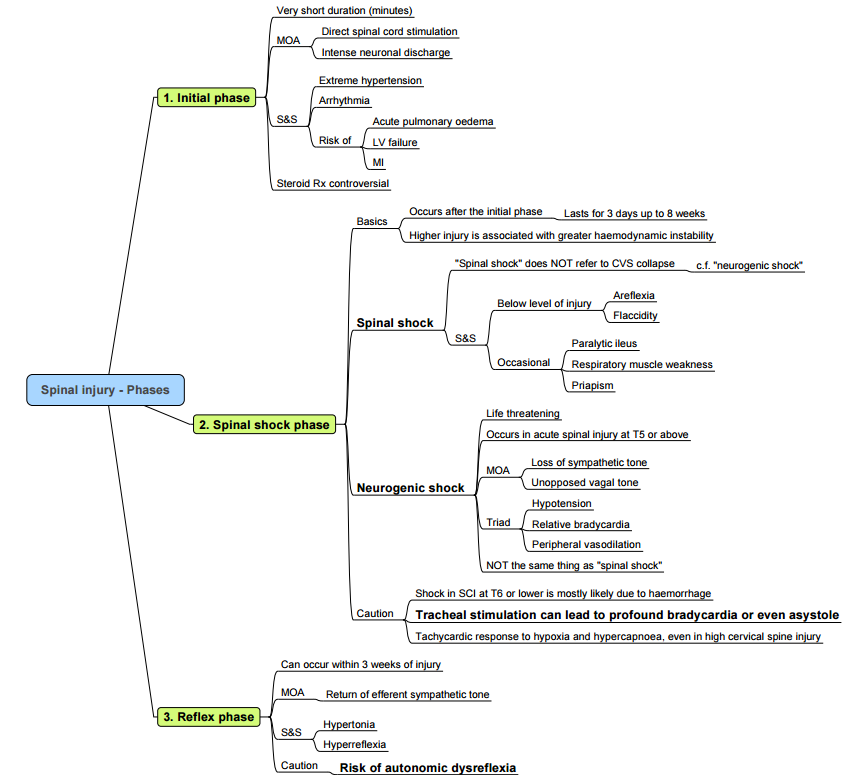

Phases after Injury

| Phase | Timing | Key features | Anaesthetic relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Seconds–minutes | Transient extreme sympathetic discharge → severe hypertension, arrhythmia, APO | Treat as hypertensive crisis; invasive BP if unstable |

| Spinal-shock | ~30 min–8 weeks | Areflexia, flaccidity, paralytic ileus; variable hypotension/bradycardia | Expect haemodynamic lability; avoid high PEEP which ↓ venous return |

| Neurogenic-shock | Usually cervical/high-thoracic injuries within first 24 h | Triad: hypotension, relative bradycardia, peripheral vasodilation | Maintain MAP ≥ 85 mmHg for 5–7 days with fluids + noradrenaline/phenylephrine |

| Reflex/Spastic | ≥ 3 weeks | Return of reflex arcs, spasticity; risk of autonomic dysreflexia (AD) above T6 | Anticipate severe peri-operative hypertension/tachy-/brady-arrhythmias |

Key Distinctions between Spinal Shock and Neurogenic Shock

| Aspect | Spinal shock | Neurogenic shock |

|---|---|---|

| Primary phenomenon | Neurological: transient loss of all motor, sensory and reflex activity below the level of injury | Haemodynamic: distributive shock from loss of sympathetic tone (vasodilatation ± bradycardia) |

| Typical cord level | Any; severity ↑ with high cervical injuries | Almost always lesions above T6 (loss of splanchnic sympathetic outflow) |

| Pathophysiology | Sudden interruption of descending facilitatory pathways → flaccid areflexia; gradual synaptic re-organisation leads to hyper-reflexia/spasticity | Loss of vasomotor tone + unopposed vagal cardiac influence → ↓ SVR, venous pooling, relative bradycardia |

| Onset | Immediate (seconds–minutes) after injury | Usually within hours of injury (can be delayed) |

| Duration | Hours → weeks (resolution heralded by bulbocavernosus reflex & return of deep-tendon reflexes) | Days → up to 6 weeks; resolves with sympathetic re-adaptation or after vasopressor support |

| Cardiovascular signs | BP normal or ↓ (if coincident neurogenic shock), heart rate often normal or tachycardic initially | Hypotension with relative bradycardia (HR < 60–80 bpm), warm peripheries, wide pulse pressure |

| Neurological signs | Flaccid paralysis, areflexia, sensory loss below lesion | May have motor/sensory loss (from SCI) but reflexes unaffected by the shock state |

| Temperature regulation | Usually normal initially; later poikilothermia as reflexes return | Impaired–patient tends to assume ambient temperature owing to vasodilatation |

| Core management | Supportive; prevent secondary cord injury (MAP ≥ 85 mmHg, oxygenation) | Fluid resuscitation + vasopressor (noradrenaline/phenylephrine); atropine/isoprenaline for severe bradycardia; treat hypothermia |

| Prognosis marker | Return of reflexes → phase-2 recovery; eventual spasticity/hyper-reflexia | Responds rapidly to haemodynamic optimisation; mortality increases if unrecognised |

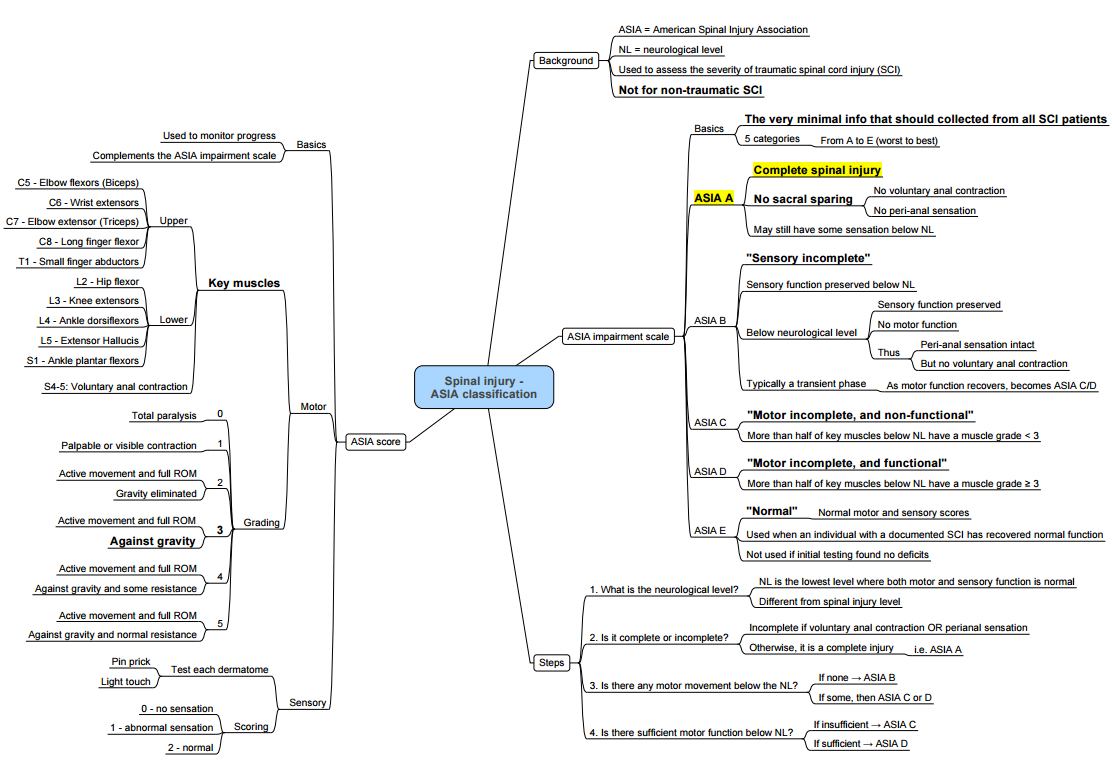

Classification

American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS)

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| A–Complete | No motor/sensory function in S4–S5 |

| B–Sensory incomplete | Sensory but no motor below lesion incl. S4–S5 |

| C–Motor incomplete | < 50 % key muscles below lesion grade ≥ 3 |

| D–Motor incomplete | ≥ 50 % key muscles below lesion grade ≥ 3 |

| E–Normal | Normal exam; prior deficits present |

The neurological level = lowest level with intact motor and sensory bilaterally.

Key Syndrome Patterns

| Syndrome | Typical cause | Ipsilateral loss | Contralateral loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brown-Séquard | Penetrating hemi-cord injury | Motor, vibration, proprioception | Pain & temperature |

| Anterior cord | Anterior spinal artery occlusion | Motor, pain, temperature | — |

| Central cord | Hyper-extension in spondylotic neck | Upper-limb > lower-limb weakness, +/- bladder retention | Variable |

| Posterior cord | Posterior spinal artery / B12 | Proprioception & vibration | — |

| Conus medullaris | L1 fracture, tumour | Mixed UMN/LMN; early sphincter dysfunction | — |

| Cauda equina | Large central disc, fracture | LMN pattern; patchy | — |

Respiratory Consequences

| Injury level | Vital capacity (% predicted) | Cough | Ventilatory support |

|---|---|---|---|

| C1–C2 | < 10 % | Absent | Permanent invasive ventilation |

| C3–C5 (phrenic) | 10–30 % | Ineffective | 80 % need ventilation within 48 h; consider NIV wean |

| Above T8 | 30–80 % | Weak | May require short-term ventilation/assisted cough |

| Below T8 | 80–100 % | ± weak | Rarely ventilated |

Early chest physiotherapy, cough assist and physiologic PEEP reduce pneumonia and atelectasis

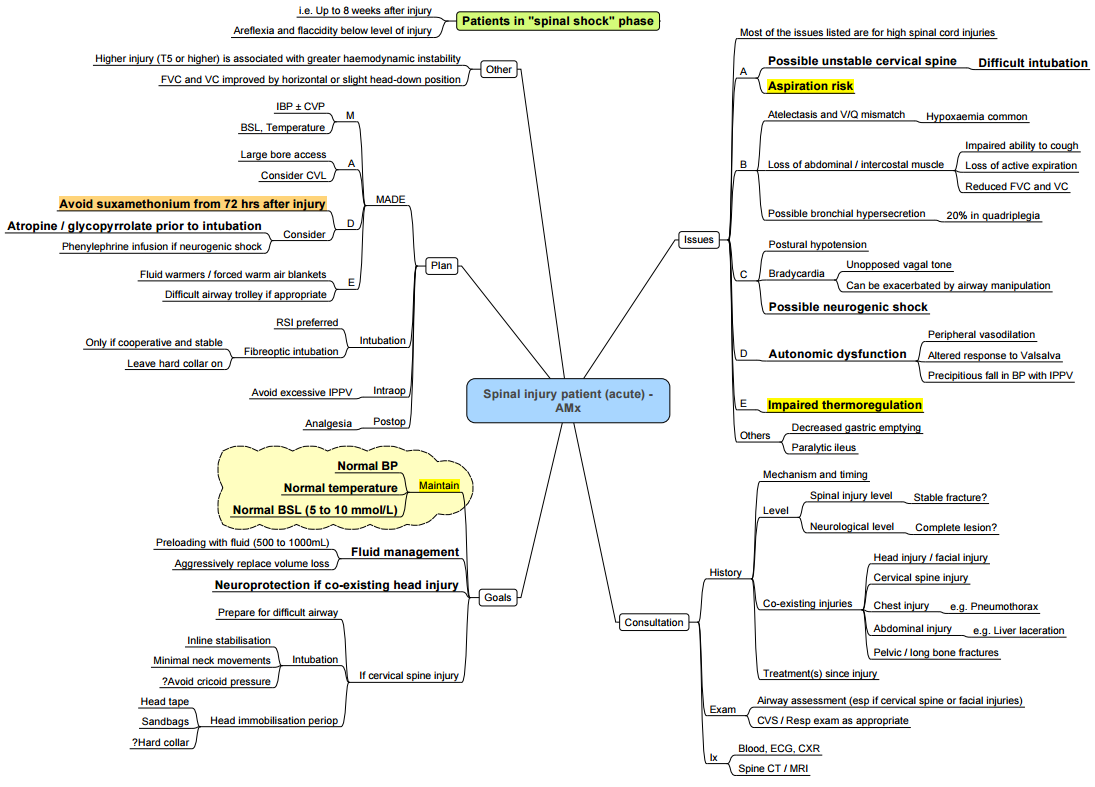

Anaesthetic Management

Pre-operative Assessment (ATLS framework)

- Airway–anticipate difficult intubation (rigid collar, limited jaw movement, chronic spasm).

- Breathing–evaluate FVC, peak cough flow; baseline ABG.

- Circulation–exclude haemorrhage; recognise neurogenic shock.

- Disability–document motor level (medico-legal).

- Exposure–pressure-area check, temperature, spasm trigger survey.

Pharmacology Pearls

| Drug/class | Evidence-based recommendation |

|---|---|

| Succinylcholine | Safe ≤ 48 h post-injury only; thereafter contra-indicated until ~9 months owing to lethal hyperkalaemia from ACh-receptor up-regulation |

| Non-depolarising NMB | Rocuronium 1 mg kg⁻¹ RSI; expect resistance in chronic phase (↑ dose/early sugammadex) |

| High-dose methyl-prednisolone | Not recommended–no neurological benefit, ↑ infection & GI bleeding risk |

| Vasopressors | Noradrenaline first-line; phenylephrine for episodic AD |

Induction & Positioning

- Manual in-line stabilisation; avoid cricoid pressure unless gastric distension.

- If awake fibre-optic needed, lignocaine 4 mg kg⁻¹ nebuliser; maintain collar.

- Warm IV fluids & forced-air blankets–impaired thermoregulation.

- Confirm BP after every position change–drastic swings common.

Maintenance Goals (“MADE”)

- M: MAP ≥ 85 mmHg.

- A: Anaemia–keep Hb > 10 g dl⁻¹ (optimises DO₂).

- D: Dysreflexia–deep anaesthesia, α-blocker (phentolamine 5 mg IV) for crises.

- E: Euthermia–36–37 °C; treat pyrexia vigorously

Autonomic Dysreflexia (chronic ≥ T6)

- Triggers: bladder/kidney stones, distended colon, labour, surgical incision.

- Presentation: SBP ↑ > 20 %, pounding headache, sweating above lesion, reflex bradycardia.

- Immediate treatment: remove stimulus, deepen anaesthesia, give GTN 2 puffs SL / nicardipine 0.5 µg kg⁻¹ min⁻¹ infusion

Ventilation

- Vₜ 6 ml kg⁻¹, permissive hypercapnia avoided (↑ ICP in concomitant TBI).

- Assisted cough (MI-E device) before extubation.

Thromboprophylaxis

- Start LMWH within 24–72 h once haemostasis secure; continue ≥ 3 months or until ambulatory. Early initiation halves VTE risk

- Add intermittent pneumatic compression.

Post-operative Priorities

- Haemodynamic monitoring for 24 h (invasive if high cervical).

- Strict temperature charting–treat poikilothermia.

- Early mobilisation/tilt-table.

- Multimodal analgesia: paracetamol, ketamine 0.1 mg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹, gabapentinoids for neuropathic pain.

- Pressure-area care checklist each nursing shift.

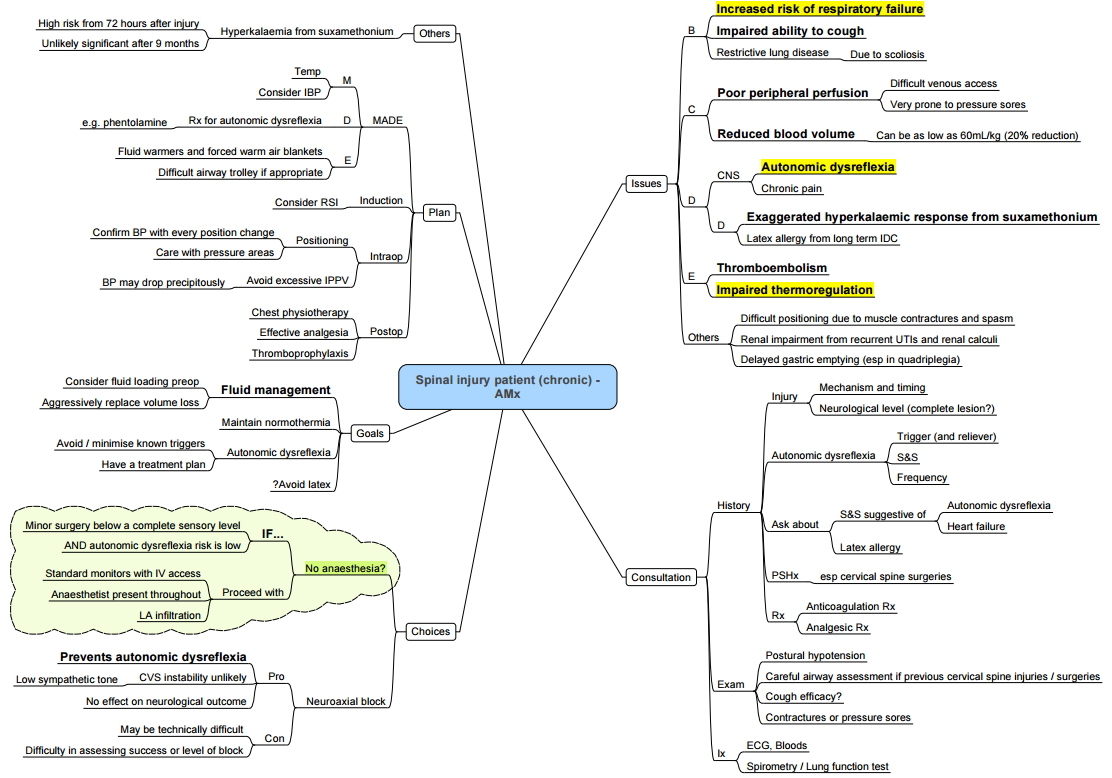

Elective / Chronic SCI Specifics

| Issue | Practical tip |

|---|---|

| Respiratory failure risk | Pre-hab with inspiratory-muscle training; plan for NIV post-op if FVC < 50 % predicted |

| Difficult IV access & reduced blood volume (~20 %) | Ultrasound lines, preload 2 ml kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ balanced crystalloids |

| Spasm & contractures | Positioning aids, baclofen pre-med |

| Latex allergy (chronic IDC) | Use latex-free equipment |

| Thermoregulation | Active warming & ambient 24 °C |

| Neurological monitoring for regional | Sensory testing unreliable below lesion; use US guidance for neuraxial/plexus blocks. |

- Minor procedures below the sensory level with low AD risk can occasionally proceed with local infiltration alone, provided IV access, standard monitors and an anaesthetist remain present throughout.

Disc Herniation

- Degenerative loss of proteoglycans → nucleus pulposus dehydration → annular tears.

- Lumbar L4/5 & L5/S1 90 %; Cervical C6/7 60 %.

- Lateral herniation → radiculopathy / cauda equina; central cervical → myelopathy.

- Anaesthetic relevance: optimise neurological exam pre-block; avoid excessive neck flexion.

American Spinal Injury (ASIA) Impairment Scale

Links

References:

- Dooney N, Dagal A. Anesthetic considerations in acute spinal cord trauma. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2011 Jan;1(1):36-43. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.79280. PMID: 22096772; PMCID: PMC3210001.

- Bonner, S. and Smith, C. (2013). Initial management of acute spinal cord injury. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care &Amp; Pain, 13(6), 224-231. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkt021

- Badhiwala JH et al. A clinical practice guideline for acute SCI: haemodynamic management. Global Spine J 2022. PMC

- Levi AD. Mean arterial pressure targets and neurologic recovery after SCI. Neurosurgery 2020. PubMed

- StatPearls. Succinylcholine Chloride (update 2025). OpenAnesthesia

- Yang J et al. Peri-operative autonomic dysreflexia review. J Anaesth Crit Care 2024. PMC

- OpenAnesthesia. Spinal cord injury–key points (2023). OpenAnesthesia

- SurgicalCriticalCare.net guideline: High-dose methylprednisolone NOT recommended (2023). Surgical Critical Care

- Medscape Reference. Corticosteroids in acute SCI (2023 update). Medscape

- PVA Consortium. Early acute management in adults with SCI (2019). Paralyzed Veterans of America

- Cardenas DD et al. Anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis after SCI. Global Spine J 2020. College of Medicine

- West CR et al. Respiratory complications in chronic SCI. BJA 2019. OpenAnesthesia

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “c8854421-a0ef-4cd7-b2cb-b51f812a729d”