- PAHCU Emergencies by Organ System

- Airway Obstruction

- Apnoea

- Haemodynamic Instability

- Cardiac Ischaemia

- Dysrhythmias

{}

PAHCU Emergencies by Organ System

Respiratory

- Airway Obstruction: Neuromuscular weakness, OSA, haematoma, oedema, vocal cord palsy, laryngospasm.

- Hypoxaemia: Neuromuscular dysfunction, neurological compromise, shunt physiology, pre-existing respiratory disease.

- Apnoea: Prematurity, neurological conditions, obstructive patterns.

- Pulmonary Oedema: Cardiogenic, post-obstructive, TRALI.

Cardiovascular

- Hypertension

- Hypotension

- Myocardial Ischaemia ± Infarction

- Pulmonary Embolism

- Arrhythmias

- Cardiac Failure

Renal

- Urinary Retention

- Oliguria: Volume depletion, intra-abdominal hypertension.

Metabolic

- Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV)

- Temperature Instability

- Shivering

Neurological

- Delirium

- Emergence Excitement

- Delayed Awakening

Airway Obstruction

- 20% of complications

- Upper airway obstruction (UAO) is the most common cause and is frequently due to loss of pharyngeal muscle tone.

- Persistent effects of anaesthetic and analgesic drugs, as well as residual neuromuscular blockade (NMB), contribute.

- Untreated airway obstruction can lead to hypoxaemia and hypercarbia, resulting in further respiratory suppression in children, dysrhythmias, hypertension, and ultimately death.

- Obstruction due to loss of muscle tone can be relieved by positioning (neck extension in the lateral position), jaw thrust manoeuvre, and/or the application of continuous positive airway pressure.

- Always consider obstructive sleep apnea (OSA):

- Patients on CPAP for OSA should be advised to bring their CPAP machines for use in the PACU.

- Upper airway obstruction (UAO) is the most common cause and is frequently due to loss of pharyngeal muscle tone.

Airway Oedema

- Surgical procedures on the tongue, pharynx, neck (including thyroidectomy and carotid endarterectomy), and cervical spine can cause localized tissue oedema or haematoma.

- Prolonged procedures in the prone or Trendelenburg position may result in airway oedema.

- Assess airway patency prior to extubation if there is concern about airway obstruction from oedema. In an awake, spontaneously breathing patient, suction the airway, deflate the cuff, and occlude the tube. Good air movement around the tube suggests the airway will remain patent after extubation.

- In patients ventilated with volume control ventilation, assess the difference in exhaled volumes before and after cuff deflation. A difference of at least 15.5% suggests successful extubation.

- A haematoma that develops in the PACU and compresses the airway may be relieved by releasing sutures or clips. However, significant fluid or blood tracking into the tissue planes of the pharyngeal wall may cause persistent airway compromise.

Post-extubation Stridor

- More common in children due to their narrow cricoid rings. Associated with repeated or traumatic intubation, changing head position during surgery, neck surgery, and bucking or coughing with the ETT in place.

- Adrenaline nebulisations (1 mg in 5 ml) help to shrink swollen mucosa. Observe the patient for at least 4 hours following resolution of symptoms due to the possibility of rebound.

Laryngospasm

Apnoea

Post-operative Apnoea

- Pre-operative conditions contributing to post-operative apnoea include OSAS, neurological conditions, and prematurity in neonates.

- In neonates, the incidence increases with decreasing postconceptual and gestational age, a history of pre-operative apnoea, and haemoglobin below 10. Premedication with caffeine (10 mg/kg) decreases the incidence related to the first two factors.

Drug-related

Reversal Agents in PACU

| Drug | Reverses | Dose | Titration Interval* | Maximum Dose | Duration of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flumazenil | Benzodiazepines | 10 µg/kg over 30 sec | 2 minutes | 1 mg/kg | 1 hour |

| Naloxone | Opiates | 1 – 2 µg/kg | 2 minutes | 1 mg/kg | 45 minutes |

- Repeat dose until desired effect achieved or maximum dose reached.

- Patients requiring reversal agents should be monitored beyond the duration of action to ensure they do not develop respiratory depression again once the reversal agent has worn off.

Haemodynamic Instability

Hypertension

- Acute post-operative hypertension in the PACU is defined as a 20% or greater increase in systemic blood pressure above baseline, which may lead to serious neurological, cardiovascular, or renal injury, as well as surgical site complications (bleeding, failure of vascular anastomosis).

- Increased sympathetic nervous system activity is the final common pathway in most cases.

Risk Factors and Triggers for Acute Post-operative Hypertension

Pre-operative Risk Factors

- Pre-existing hypertension

- Pre-existing renal disease

- Advanced age

- Drug rebound (e.g., antihypertensive drugs not given pre-operatively)

Post-operative Triggering Events

- Arterial hypoxaemia and/or hypercapnoea

- Pain

- Hypervolaemia

- Emergence excitement/agitation

- Shivering

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Bowel distention

- Urinary retention

- Treating triggering events may be sufficient, but if hypertension continues despite relief of these triggers, consider using short-acting intravenous antihypertensive agents (TNT, Dihydrallazine, and Labetalol).

- It is essential to know the pre-operative blood pressure to target this post-operatively, avoiding over-aggressive correction in vascular beds that have adjusted to a pre-existing raised pressure.

Hypotension

Hypovolaemia

- May be due to ongoing losses (bleeding, 3rd space fluid translocation), inadequate replacement of intra-operative losses, or loss of sympathetic nervous system tone due to central neuraxial blockade.

- Patients with hypovolaemia will respond to a leg raise test (if feasible) and should be treated with volume replacement, except when persistent central neuraxial blockade is suspected, in which case vasoconstrictors should be considered.

- If ongoing bleeding is suspected, perform serial bedside haemoglobin tests to help confirm the diagnosis.

- Consider and correct coagulopathy if present, or inform the surgeon if a surgical bleeder is suspected.

- Patients taking beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers may not develop tachycardia in response to hypovolaemia or anaemia.

Distributive

| Cause | Details | Core Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Sympathectomy | High (>T4) sympathectomy will ↑ cardiac sympathetic tone and arterial tone | Fluids, Vasopressors |

| Sepsis | Urinary and biliary tract procedures in particular carry a risk of sudden onset severe sepsis with hypotension | Take cultures, Start antibiotics, Supportive therapy (fluids, vasopressors, inotropes) |

| Allergic reaction | Consider drugs (muscle relaxants, antibiotics, etc.), colloids, latex | Fluids, Adrenaline |

| Critical illness | With underlying high sympathetic tone, small doses of anaesthetic agents, opioids, or sedative hypnotics may cause marked hypotension | Supportive therapy (fluids, inotropy) |

Cardiogenic

- Post-operative hypotension may be due to ischaemia, infarction, cardiomyopathy, tamponade, or arrhythmia. Consider the patient’s pre-operative condition, cardiac risk, and the nature of the procedure in the analysis.

Cardiac Ischaemia

Myocardial Ischaemia Non-ST-segment Elevation (MINS)

- High-risk patients should be monitored with a 5-lead ECG. Ischaemia may not be accompanied by pain in the post-operative period, and any ST segment or T-wave changes should be evaluated further.

- Monitoring of Lead II and V5 should detect approximately 80% of post-operative MIs detected by 12-lead ECG.

- Recommended that a patient with known or suspected coronary artery disease who has undergone intermediate or high-risk surgery have a 12-Lead ECG performed routinely in the PACU.

Dysrhythmias

Common Causes of Post-operative Cardiac Dysrhythmias

Pre-operative Risk Factors

- Pre-existing hypertension

- Advanced age

- Drug rebound (e.g., cardio-active drugs not given pre-operatively)

Post-operative Triggering Events

- Arterial hypoxaemia and/or hypercapnoea

- Pain

- Hypervolaemia

- Electrolyte disturbances (esp. potassium, magnesium)

- Emergence excitement/agitation

- Shivering

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Bowel distention

- Urinary retention

- Serious causes of tachyarrhythmia to consider and treat include bleeding, cardiogenic or septic shock, pulmonary embolus, thyroid storm, and malignant hyperthermia.

- New-onset atrial dysrhythmias occur in up to 10% of major non-cardiothoracic surgery cases, and even more in cardiothoracic surgery cases. The risk increases with pre-existing cardiac risk factors, fluid overload, electrolyte disturbance, and hypoxaemia.

- Ventricular dysrhythmias are usually due to increased sympathetic tone and will respond to treatment of the cause.

- Bradydysrhythmias are frequently drug-related (opioids, beta-blockers, anticholinesterases, dexmedetomidine), vagal-related to the procedure (bowel or bladder distention, raised intraocular or intracranial pressure), or due to a high neuraxial block with block of the cardiac accelerator fibers.

Emergence Delirium in Children

Emergence Delirium

- Emergence delirium (ED) is a disturbance in a child’s awareness of and attention to their environment, characterized by disorientation and perceptual alterations.

- This dissociated state of consciousness, where the child is irritable, uncompromising, uncooperative, and combative, typically occurs within the first 30 minutes of arrival in the recovery room and is usually self-limited, lasting 5-15 minutes.

- The incidence of ED has risen with the use of Sevoflurane. Depending on the definition, the incidence of ED varies from 10 – 50%.

Possible Aetiological Factors for ED

| Aetiology | Comments |

|---|---|

| Rapid emergence | Associated with all volatiles but mostly Sevoflurane and Desflurane |

| Intrinsic characteristics of anaesthetic agents | May occur even if Sevo used only for induction |

| Inadequately treated pain | |

| Type of surgery | Tonsillar, thyroid, middle ear or eye surgery |

| Age 2-5 years | Possibly due to psychological immaturity |

| Pre-operative anxiety | Not proven |

| Temperament | Ability to adapt to environmental changes |

| Other drugs which may affect behaviour | Anti-cholinergics, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, opiates, etc |

Prevention

- Good analgesia

- Propofol (TIVA or a bolus of 1 mg/kg at the end of surgery)

- Ketamine (intranasally pre-op or IV at the end of surgery)

- Alpha adrenoreceptor agonists (clonidine or dexmedetomidine)

- Fentanyl

- Slow wake-up in a quiet area

- Note that much of the above may delay emergence, so weigh up the risk/benefit.

Treatment

- Pre-emptive strategies include an anxiolytic premed (although benzodiazepines have also been associated with increased ED) and adequate analgesia; there is insufficient evidence to advise against the use of newer volatiles.

- The child should be nursed in a quiet, darkened recovery area.

- Physical restraint may be required to prevent self-injury; this is best accomplished by holding.

- Reuniting the child with a parent may be helpful. ED is generally self-limiting and will resolve with time (usually within 15 minutes).

- The decision to medicate depends on severity.

Pharmacological Treatment Options for ED

| Drug | Dose (IV) |

|---|---|

| Midazolam* | 0.02-0.1 mg/kg |

| Fentanyl | 1 – 2 µg/kg |

| Propofol | 0.5 -1 mg/kg |

| Droperidol | 20 µg/kg |

| Clonidine | 1 – 2 µg/kg |

| Dexmedetomidine | 0.5 µg/kg |

- Midazolam has been identified as a possible triggering agent for ED.

Delayed Awakening

- A patient should be responsive to stimulation within 60 – 90 minutes of the end of an anaesthetic, even in long procedures.

Causes of Delayed Emergence from Anaesthesia

- Residual drug effect (especially in patients with delayed elimination, e.g., renal/hepatic disease)

- Hypothermia

- Hypoglycaemia

- Intracranial event (raised pressure, CVA)

- Evaluate vital signs (BP, SaO2, Temperature, ECG), perform a neurological examination (reflexes may be brisk in the immediate post-operative period), check glucose and electrolytes, and consider a CT scan. If residual drug effects are contributing, consider reversal agents.

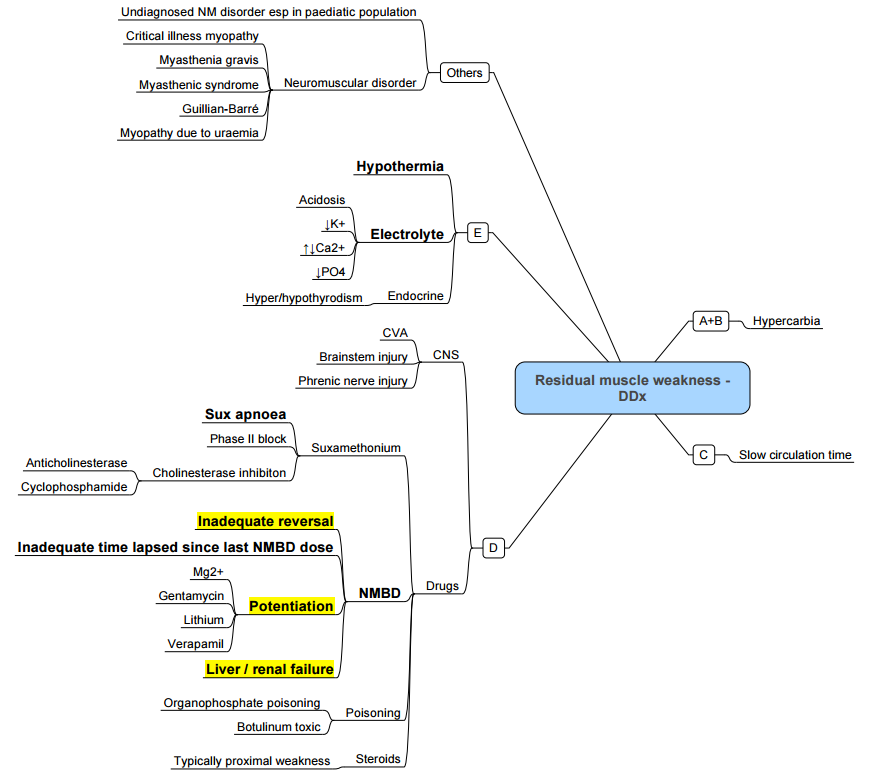

Residual Muscle Weakness

- The diaphragm recovers from the effects of muscle relaxants before the pharyngeal muscles do so that respiratory effort may be adequate in the face of pharyngeal musculature still weak from the effects of residual neuromuscular blockade.

- Train-of-four measurements can be misleading as adequate respiration will occur from a ratio of 0.7 but pharyngeal function is only recovered once the ratio reaches 0.9.

- In an anaesthetised patient a post tetanic count is a more reliable indicator of return of function. In an awake patient the ability to strongly oppose the incisors against a tongue depressor is a more reliable indicator of pharyngeal muscle tone, correlating with an average train-of-four ratio of 0.85 compared with 0.6 for sustained head lift.

Prolonged NDMB

Factors Contributing to Prolonged Non-depolarising Neuromuscular Blockade

Drugs

- Inhaled anaesthetic drugs

- Local anaesthetics (lignocaine)

- Cardiac dysrhythmics (procainamide)

- Antibiotics (aminoglycosides, lincosamines, metronidazole, tetracyclines, polymixins)

- Corticosteroids

- Calcium channel blockers

- Dantrolene

Metabolic and Physiologic States

- Hypermagnesaemia

- Hypocalcaemia

- Hypothermia

- Respiratory acidosis

- Hepatic/Renal failure

- Myasthenic syndromes

Prolonged DMB

Factors Contributing to Prolonged Depolarising Neuromuscular Blockade

- Excessive dose of succinylcholine

Reduced Plasma Cholinesterase Activity

- Decreased levels (extremes of age, disease states hepatic disease, uraemia, malnutrition, plasmapheresis)

- Hormonal changes

- Pregnancy

- Contraceptives

- Glucocorticoids

Inhibited Activity

- Irreversible (echothiophate)

- Reversible (neostigmine, pyridostigmine, edrophonium)

Genetic Variant

- Atypical plasmacholinesterase

Links

- Recovery

- Anaesthesia emergencies

- Post op MI

- Organ protection

- Anaesthesia and renal disease

- Post operative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

- Post operative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) and delirium

- Post operative vision loss (POVL)

- Paediatric post op complications

- Paediatric ENT

References:

1. Javed H, Olanrewaju OA, Ansah Owusu F, Saleem A, Pavani P, Tariq H, Vasquez Ortiz BS, Ram R, Varrassi G. Challenges and Solutions in Postoperative Complications: A Narrative Review in General Surgery. Cureus. 2023 Dec 22;15(12):e50942. doi: 10.7759/cureus.50942. PMID: 38264378; PMCID: PMC10803891.

2. 1Miller RD, editor. Miller’s Anesthesia. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019.

3. Butterworth JF, Mackey DC, Wasnick JD, editors. Morgan & Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018.

4. Smith I, Kranke P, Murat I, Smith A, O’Sullivan G, Søreide E, et al. Perioperative fasting in adults and children: guidelines from the European Society of Anaesthesiology. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2011;28(8):556-569.

5. Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Connis RT, Abdelmalak BB, Agarkar M, Dutton RP, et al. 2022 American Society of Anesthesiologists Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2022;136(1):31-81.

6. Myles PS, Weitkamp B, Jones K, Melick J, Hensen S. Validity and reliability of a postoperative quality of recovery score: the QoR-15. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(5):685-691.

7. Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, Chung F, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, et al. Fourth consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2):411-448.

8. Brull SJ, Kopman AF. Current status of neuromuscular reversal and monitoring: challenges and opportunities. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(1):173-190.

9. Mitchell V, Dravid RM, Patel A, Swampillai C, Higgs A. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of tracheal extubation. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(3):318-340.

10. Gertler R, Brown HC, Mitchell DH, Silvius EN. Dexmedetomidine: a novel sedative-analgesic agent. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2001;14(1):13-21.

11. Yentis SM, Malhotra S. Analgesia, anaesthesia and pregnancy: a practical guide. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2022.

12. Post Anaesthesia Care Unit Emergencies Dr. R Gray. UCT refresher 20111

Summaries:

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “1132355a-f505-4a82-9b76-8207f440f3f5”