- Valvular Heart Disease

- Fixed Cardiac Output Lesions

- Aortic Stenosis

- Mitral Stenosis

- Volume Overloaded Lesions

- Pathophysiological Stages

- Aortic Regurgitation

- Pathophysiology

- Mechanism

- Clinical Findings

- Causes

- Clinical History

- Special Investigations

- Indications for Surgery

- History

- Anesthesia Management

- Pressure Volume Loop

- Mitral Regurgitation

- Pathophysiology

- Causes

- Clinical Findings

- Investigations

- History

- Indications for Surgery

- Anesthesia Management

- Pressure Volume Loop

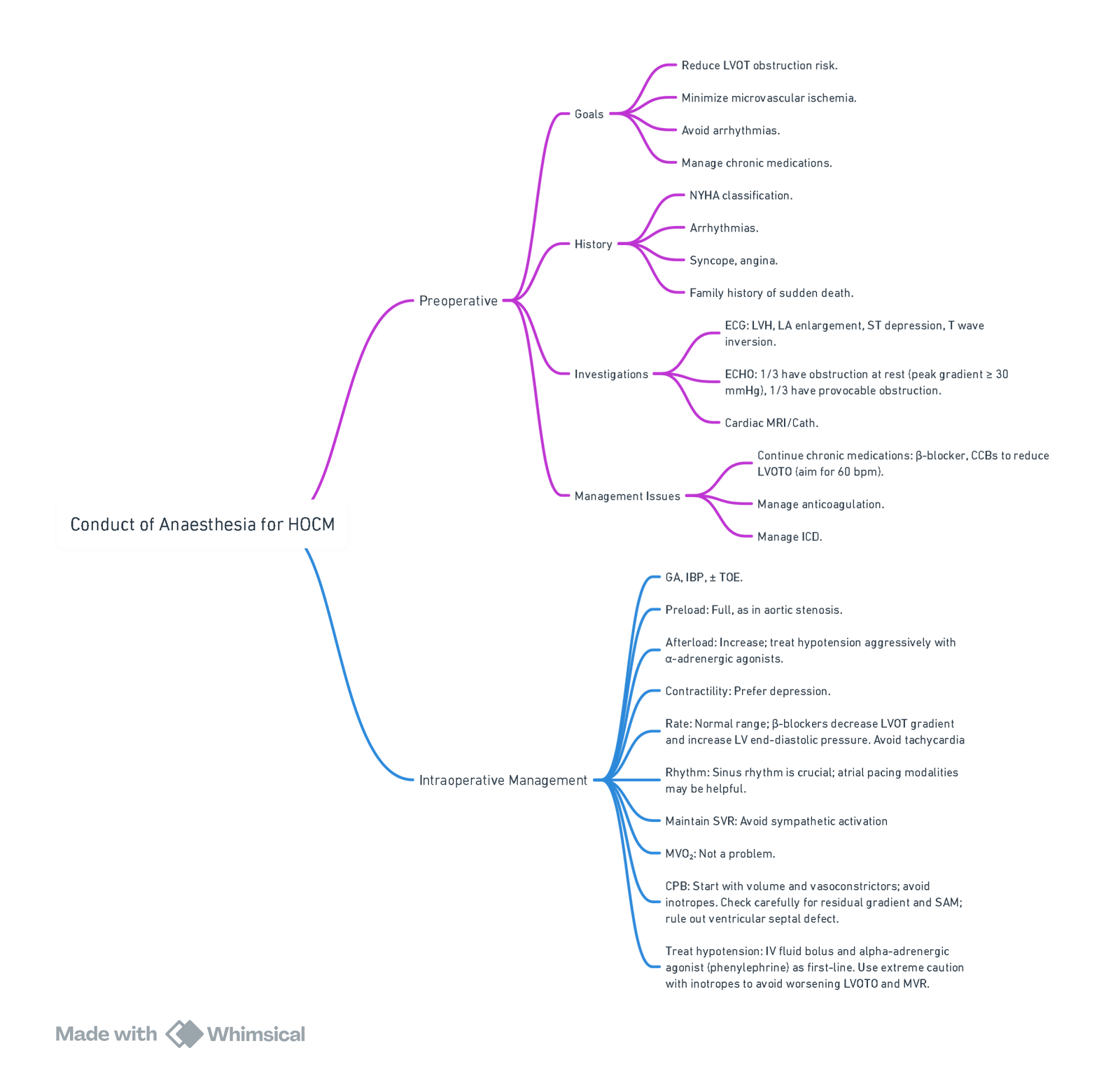

- Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

- Complications

- Differentiating Aortic Stenosis from HOCM

- Anesthetic Management for HOCM

- HOCM in Pregnancy

{}

Valvular Heart Disease

Incidence

Developed World

- Average incidence: 2.5%

- 18-44 years: 0.7%

- Older than 75 years: 13.3%

Developing World

- 15.6 million affected by rheumatic heart disease (RHD)

- 1% of school-age children affected by RHD

Lesions

- Aortic Stenosis

- Mitral Stenosis

- Aortic Regurgitation

- Mitral Regurgitation

Perioperative Considerations

Risk Assessment

- Consider the increased perioperative risk in patients with valvular heart disease.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Determine the need for antibiotic prophylaxis based on current guidelines to prevent infective endocarditis.

Anticoagulation

- Manage anticoagulation carefully, especially in patients with atrial fibrillation, prosthetic valves, or slow flow.

Associated Comorbidities

- Congestive heart failure (CHF), both systolic and diastolic

- Thrombosis

- Rhythm abnormalities

Hemodynamic Goals

- Maintain optimal hemodynamics to prevent exacerbation of valvular heart disease complications.

Drug Management

- Anticoagulation: Withdraw oral anticoagulants 72 hours prior to surgery, reduce INR to 1.5, maintain with unfractionated heparin (UFH) to keep APTT at twice the control.

- β-Blockers: Titrate to the heart rate appropriate for the specific valvular lesion, particularly in stenotic conditions.

- Statins: Continued use is associated with better outcomes.

- Recombinant BNP (Nesiritide): Useful in reducing pulmonary artery pressure, myocardial oxygen consumption, and increasing coronary flow and urine output. Beneficial in high-risk patients with severe mitral regurgitation, pulmonary hypertension, and left ventricular dysfunction.

Fixed Cardiac Output Lesions

- Patients with fixed cardiac output lesions cannot compensate for reductions in systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

- The severity of stenosis correlates with higher pressure gradients across the valve.

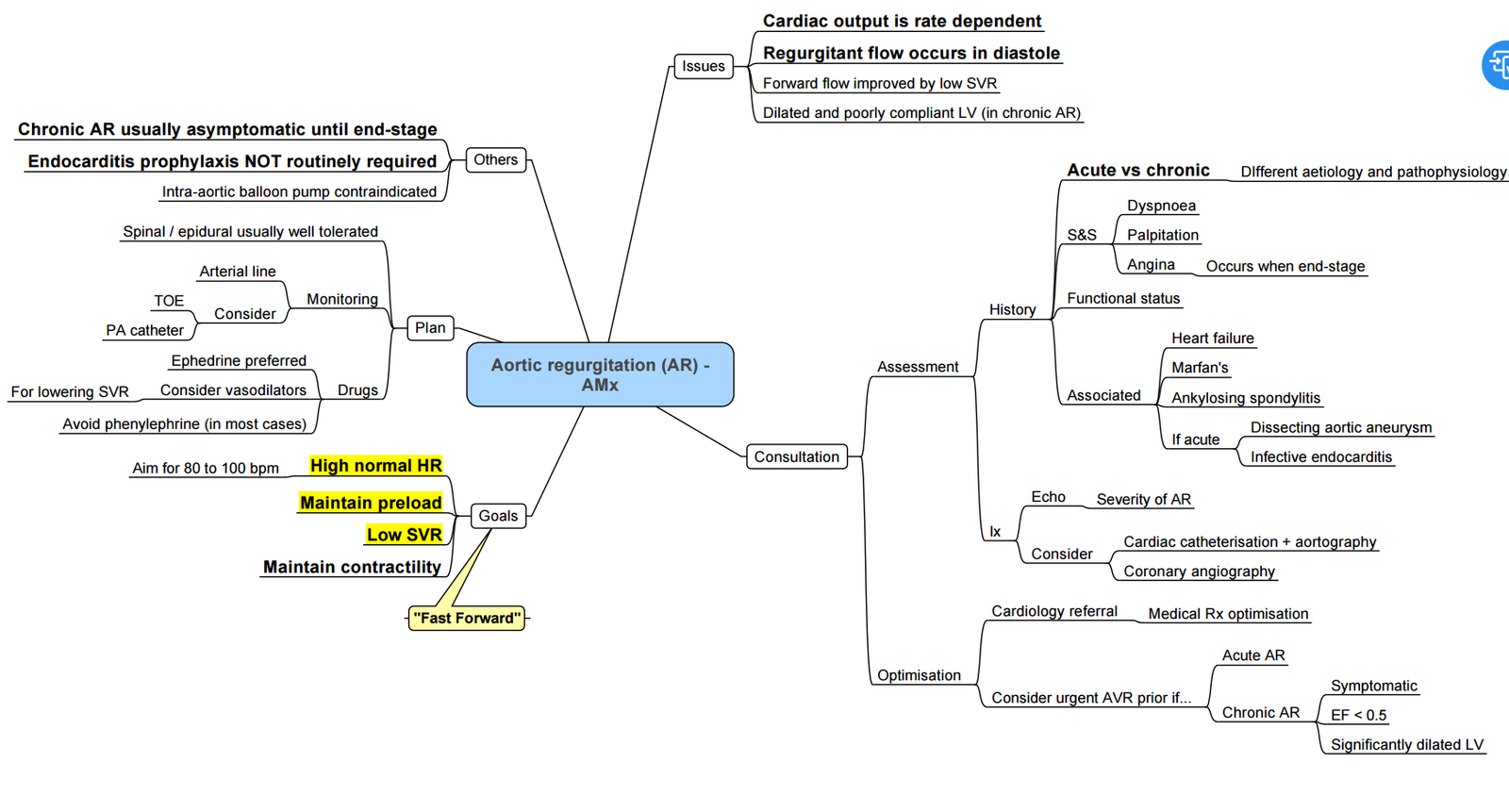

Aortic Stenosis

Etiology

Most Common Causes

- Degenerative: Common in patients >70 years due to long-term wear and tear.

- Congenitally malformed valve: Such as a bicuspid valve.

- Untreated Group A Streptococcus URTI: Leads to rheumatic valve disease.

- Valve inflammation.

Pathophysiology

Valve Changes

- Fibrosis and calcification: Impede blood flow through the aortic valve.

- Left Ventricle (LV) Changes:

- Increased LV contraction to overcome valvular resistance.

- High LV-to-aorta pressure gradient initially maintains cardiac output.

- Concentric LV hypertrophy develops over time, leading to decreased cardiac output and pulmonary congestion.

Compensatory Mechanisms

- Left atrium dilation and hypertrophy due to pressure overload.

- Cardiac output becomes more reliant on atrial filling.

- Atrial fibrillation significantly decreases cardiac output.

Consequences

- Outflow obstruction leads to LV hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, increased LVEDP, subendocardial ischemia, LV failure, and low gradient AS.

Key Pathophysiological Points

- Concentric LVH: Increased LVEDP, decreased coronary perfusion pressure (CPP), and reduced oxygen delivery.

- Worsening AS: Leads to lower CPP and decreased diastolic aortic pressure.

- LVH Effects: Decreased LV compliance, higher filling pressures, and diastolic dysfunction.

- Inadequate neovascularization: Insufficient for hypertrophied heart.

- Prolonged isovolumic relaxation: Shortens diastole, reducing coronary perfusion time.

Clinical Findings

Signs/Symptoms

- Systolic ejection murmur: Audible during systolic contraction.

- Syncope and dyspnea on exertion: Due to insufficient cardiac output.

- Angina on exertion: High oxygen demands of hypertrophied muscle and reduced coronary perfusion.

- Pulmonary congestion: Causing diffuse crackles and dyspnea.

Murmur

- Location: Loudest at the right base, radiating broadly and upwards.

- Timing: Mid-holosystolic, late peaking.

- Quality: Harsh.

- Gallavardin Phenomenon: High-frequency murmur radiating to the apex.

Associated Findings

- Pulsus parvus et tardus

- Reduced carotid volume

- Sustained apical pulse

- Soft S2

Differentiating Aortic Stenosis from Aortic Sclerosis

- Aortic Stenosis:

- Reduced pulse pressure (< 40)

- Delayed carotid upstroke

- Diminished or paradoxically split S2

- Radiation to RCA and right clavicle

- Aortic Sclerosis:

- Normal pulse pressure

- Normal carotid upstroke

- Normal S2

- No radiation

Investigations

ECG

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

Chest X-ray

- Calcified aortic valve

Echo

- Assesses valve anatomy, calcification, and pressure gradient to grade severity.

Severity Assessment

- Valve Area:

- Normal: 2.6 – 3.5 cm²

- Mild: 1.2 – 1.8 cm²

- Moderate: 0.8 – 1.2 cm²

- Significant: 0.6 – 0.8 cm²

- Critical: < 0.6 cm²

- Mean Gradient:

- Mild: 12 – 25 mmHg

- Moderate: 25 – 40 mmHg

- Significant: 40 – 50 mmHg

- Critical: > 50 mmHg

Complications

- Heyde’s Syndrome: Bleeding due to angiodysplasia + AS.

- Endocarditis

- Emboli

- Decreased cardiac output

- LV hypertrophy and myocardial dysfunction

- Pulmonary congestion

- Atrial fibrillation

Indications for Surgery

- Symptomatic patients with severe AS.

- Symptoms do not correlate well with severity; asymptomatic patients with small valve areas may have a good prognosis until symptoms develop.

- Once symptomatic, the prognosis worsens with an increased risk of sudden death.

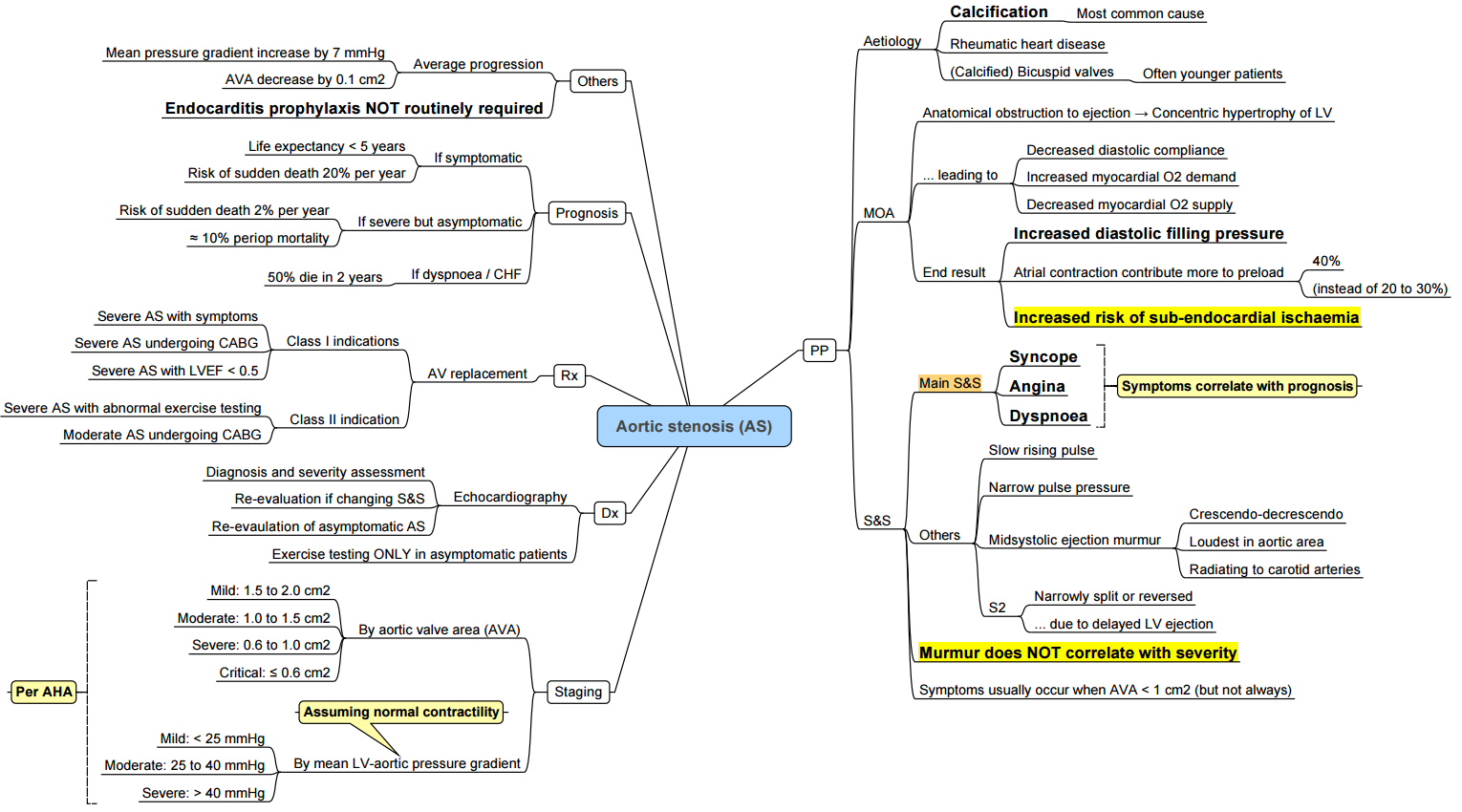

Anesthetic Considerations for Aortic Valve Stenosis

Hemodynamic Goals (CRRAP Goals)

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Overview of the Valve Lesion

Severe aortic stenosis (AS) causes left ventricular (LV) outflow obstruction, resulting in LV pressure overload, concentric hypertrophy, diastolic LV dysfunction, decreased stroke volume, and cardiac output (CO).

Preoperative Considerations

During the preanesthetic consultation and review of cardiac diagnostic studies, attention is paid to:

- Severity of AS

- Presence of associated aortic regurgitation (AR)

- Other cardiac valve pathology

- LV and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction

- Coexisting coronary artery disease

Patients with AS and a high pulmonary-systemic ratio (mean pulmonary arterial pressure/mean systemic arterial pressure) are at greater risk for perioperative morbidity and mortality. In the immediate preoperative period, the anesthesiologist may administer small incremental doses of short-acting agents such as intravenous benzodiazepine (e.g., midazolam 0.5 to 1 mg) and/or an opioid (e.g., fentanyl 25 to 50 mcg) to reduce the stress response. Extra caution is warranted for patients with critical AS, severe ventricular dysfunction, or age >75 years.

Prebypass TEE Assessment

Prior to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) focuses on:

- Confirming the presence of AS (e.g., heavily calcified or poorly mobile aortic valve leaflets)

- Measuring aortic annulus, aortic root, and sinotubular junction diameters

- Quantifying AS severity

Continuous-wave Doppler measurement of the transvalvular gradient is typically obtained from deep transgastric or transgastric long-axis views. Severe AS is not excluded if the valve appearance suggests this diagnosis, even if the mean aortic valve gradient is <40 mm Hg. Calculating aortic valve area requires alignment with maximum LVOT and aortic jet velocities. Planimetry of the aortic valve orifice during systolic opening provides an alternative estimate of effective aortic valve area but has technical limitations.

Significant ventricular septal hypertrophy and systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve should be assessed. Ventricular septal myectomy may be necessary to prevent postoperative dynamic LVOT obstruction.

Identifying coexisting significant AR is crucial for deciding cardioplegia administration. A congenital bicuspid aortic valve can cause severe AS and/or AR and may require repair if associated with ascending aorta dilation.

Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR)

SAVR involves the following steps:

- Midline Sternotomy and Aortic Cannulation: Followed by initiating CPB.

- Cardioplegia: To establish diastolic cardiac arrest.

- Aorta Opening and Valve Excision: Removal of all calcific debris to minimize the risk of cerebral infarction.

- Prosthetic Valve Implantation: Measurement of the aortic annulus and implantation of the prosthetic valve.

- Aorta Closure and Air Removal: Ensuring no residual air in the ascending aorta and left heart chambers.

- Heart Reperfusion and CPB Weaning: Monitoring with TEE and attaching epicardial pacing wires to the right atrium and RV.

Postbypass TEE Assessment

After aortic cross-clamp removal and restoration of systemic blood pressure, initial TEE examination identifies unacceptable surgical issues such as stuck leaflets and significant paravalvular leaks. Post-CPB, TEE confirms normal prosthetic valve function, examines adjacent structures for collateral damage, and assesses LV and RV function.

Postbypass Management

Post-AVR, inotropes are generally unnecessary due to well-preserved LV contractility. Management of hypertension, which increases the risk of arterial bleeding and aortic dissection, involves increasing anesthetic depth and using vasodilator drugs. Short-acting beta-blockers like esmolol may be necessary.

AV conduction abnormalities are common post-AVR, necessitating immediate postoperative epicardial pacing.

Pressure-volume Loop

Mitral Stenosis

Pathophysiology

- Rheumatic Fever: Most common cause.

- Recurrent Inflammation: Leads to thickening and shortening of chordae tendineae.

- Fibrous Deposition and Calcification: Affects mitral valve leaflets and chordae tendineae.

- Fusion of Commissures: Thickening and stiffening of junction between valve leaflets.

Mechanism

- Opening Snap (following S2): Indicates sudden tensing of chordae tendineae and mitral valve leaflets.

- Mid-Diastolic Rumble: Turbulent flow across the valve during diastole.

- Thickened and Stiff Leaflets: Decreased area of the mitral valve orifice.

- Obstructed Blood Flow: Increased pressure gradient across the mitral valve.

- Impaired Emptying of Left Atrium:

- Increased pulmonary vasculature resistance and hydrostatic pressure.

- Increased left atrial pressure.

- Left Atrial Enlargement:

- Compression of surrounding structures (e.g., esophagus causing dysphagia, recurrent laryngeal nerve causing hoarseness).

- Stretching of atrial conduction fibers leads to atrial fibrillation.

- Impaired filling of the left ventricle.

- Right-Sided Heart Failure, Cardiogenic Shock, Congestive Heart Failure: Secondary complications from increased pulmonary pressures.

Clinical Findings

- Dyspnea: Due to pulmonary edema.

- Left Parasternal Lift: Indication of right ventricular hypertrophy.

- Infective Endocarditis: Risk due to damaged mitral leaflets.

- Pre-Systolic Accentuation: Murmur intensity increases with atrial contraction (absent in atrial fibrillation).

- Intense S1 in Early Stages: Thickened and calcified leaflets.

Causes

- Rheumatic heart disease, infective endocarditis, congenital abnormalities, and calcification.

- Most common valvular lesion in pregnancy.

Clinical

- Symptoms related to pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure.

Murmur

- Location: Apex (isolated apical)

- Timing: Mid-diastole

- Quality: Low-frequency rumble, best heard in the left lateral decubitus (LLD) position with pre-systolic accentuation.

Associations

- Loud S1, atrial fibrillation, poor palpable apex beat

- Pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular heave, P2 tap, increased JVP, increased A waves

- Normal or decreased pulse

Investigations

CXR

- Enlarged left atrium; advanced disease shows enlarged right ventricle and right atrium.

- Double density sign (occurs when the right side of the left atrium extends behind the right cardiac shadow, indenting the adjacent lung and forming its own distinct silhouette)

- Splaying of the carina (>90 degrees)

ECG

- Left atrial enlargement: P mitrale.

- Signs of PHT and right heart involvement.

- Right axis deviation, RBBB, Dominant R in V1

Echo

- Assess valve anatomy, calcification, and gradient across the valve.

Valve Surface Area

- Normal: 4 – 6 cm²

- Symptom-free until: 1.5 – 2.5 cm²

- Moderate stenosis: 1 – 1.5 cm²

- Critical stenosis: < 1 cm²

Grading of Mitral Stenosis

- Mild: Mean gradient < 5 mmHg, PA systolic pressure < 30 mmHg, valve area > 1.5 cm²

- Moderate: Mean gradient 5-10 mmHg, PA systolic pressure 30-50 mmHg, valve area 1.0-1.5 cm²

- Severe: Mean gradient > 10 mmHg, PA systolic pressure > 50 mmHg, valve area < 1.0 cm²

Hemodynamic Consequences

- Obstructed flow across mitral valve leads to increased left atrial pressure, dilation, and atrial fibrillation with thromboembolic complications.

- Decreased left ventricular filling leads to muscle atrophy, scarring, LV dysfunction, and decreased ejection fraction (EF).

- Elevated pulmonary pressures cause right ventricular hypertrophy and failure.

Indications for Surgery

- Symptomatic patients have a poor prognosis without intervention.

- NYHA II, III, IV with mitral valve orifice <1.5 cm² and pulmonary hypertension.

Prognosis

- Survival in asymptomatic patients is good for up to 10 years.

- Sudden deterioration can be precipitated by atrial fibrillation, pregnancy, embolism, sepsis.

- Symptoms appear once valve area <2.5 cm²; resting symptoms when valve area <1 cm².

Anesthesia Management

- Mild MS with good exercise tolerance and no pulmonary hypertension (PAPs <50 mmHg): Minimal risk for non-high-risk surgery if heart rate is controlled perioperatively with beta-blockers.

- Severe MS or pulmonary hypertension (PAPs >50 mmHg): Significant risk; consider percutaneous mitral commissurotomy.

- Maintain heart rate at 50-70 bpm to maximize diastolic filling of LV. Maintain sinus rhythm; cardiovert if atrial fibrillation occurs perioperatively.

- Preserve systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

- Avoid hypercarbia, acidosis, and hypoxia to prevent exacerbation of pulmonary hypertension.

- Consider invasive monitoring and ICU or high-care postoperatively. Use inotropes and alpha-agonists as needed.

Overview of the Valve Lesion

Severe chronic mitral stenosis (MS) results in impaired left ventricular (LV) filling due to a fixed obstruction to left atrial (LA) outflow. This condition increases LA pressure, pulmonary artery pressure, and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), commonly leading to atrial fibrillation (AF), chronic pulmonary hypertension, and eventually right ventricular (RV) failure. The LV is typically “underloaded” but may develop myocardial fibrosis, impairing both systolic and diastolic function.

- Causes: Rheumatic heart disease is the most common cause, resulting in thickened and rolled leaflet edges, commissural fusion, and subvalvular changes like chordal shortening and valve thickening. Severe mitral annular calcification is another significant cause, with calcification involving the leaflets. Other causes include infiltrative diseases and congenital abnormalities.

Preoperative Considerations

During the preanesthetic consultation, particular attention is paid to the severity of MS, associated mitral regurgitation (MR), other cardiac valve pathology, the presence of LA or left atrial appendage (LAA) thrombus, and RV dysfunction severity. The chest radiograph (CXR) may reveal signs of pulmonary edema and right heart enlargement in advanced cases.

- Medical Optimization: Patients should receive optimized medical therapy before elective surgery, but surgery should not be delayed in symptomatic patients.

- Heart Rate Control: Controlling heart rate and avoiding tachycardia is crucial. Antiarrhythmic and antitachycardia drugs are maintained up to and on the day of surgery. Small incremental doses of short-acting intravenous benzodiazepine (e.g., midazolam 1-2 mg) may be given preoperatively to avoid tachycardia due to anxiety.

- Anticoagulation Therapy: Many patients with severe MS and AF are on chronic anticoagulation therapy, requiring careful management of medications affecting hemostasis.

Prebypass Hemodynamic Management

- Sinus Rhythm

- Have defibrillator, pads and amiodarone ready

- HR: 60-70

- Maintain and augment preload, contractility and afterload

- Maintain coronary perfusion pressure

- Prevent increased PVR

Prebypass TEE Assessment

Prior to cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), the transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) examination confirms the presence and quantifies the severity of MS. Indicators include a thickened valve with reduced leaflet opening and high-velocity aliased mitral inflow on color-flow Doppler imaging. Continuous-wave Doppler measures the transvalvular gradient, with a mean gradient usually >5-10 mmHg in severe MS, depending on heart rate and stroke volume. The degree of concomitant MR is also assessed.

- LA and LAA Examination: The LA and LAA are checked for spontaneous echo contrast or thrombus. An echocardiography contrast agent may be needed to differentiate between them.

- RV Assessment: The RV is examined for dysfunction or dilatation due to chronic pulmonary hypertension. Severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) with tricuspid annular dilation may indicate the need for concomitant tricuspid valve repair.

Surgical Mitral Valve Repair, Commissurotomy, or Replacement

Mitral valve surgery for MS includes repair, commissurotomy, or replacement. Valve replacement is most common in patients with rheumatic MS who are not candidates for or have failed percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy. The surgical approach is similar to that for mitral valve surgery for MR.

- Severe Mitral Annular Calcification: Surgical or transcatheter mitral valve replacement is required to relieve obstruction as percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty or surgical valve repair is ineffective. Severe calcification complicates surgery and is associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Postbypass TEE Assessment

After mitral valve replacement, TEE assesses for paravalvular leak, high gradient across the mitral prosthesis (indicating iatrogenic mitral stenosis), and residual communication between the LAA and LA if the LAA was ligated. Possible damage to adjacent structures (e.g., aortic valve or circumflex coronary artery) is ruled out. TEE also guides the removal of residual air.

Postbypass Management

Due to chronic “underloading” of the LV, there is a risk of acute failure post-CPB separation. Inodilator agents like milrinone infusion may be used, particularly in patients with elevated PVR and coexisting RV dysfunction. Low-dose dopamine or norepinephrine may be necessary to avoid systemic vasodilation.

- Right Heart Failure: Acute refractory right heart failure with high PVR may occur during CPB weaning. Management strategies are detailed in related topics.

- Arrhythmias: AF and other arrhythmias are common postbypass. Treatment includes synchronized cardioversion and administration of amiodarone, with correction of potassium and magnesium levels to high-normal values.

- Bleeding: Common post-CPB complication. Intractable bleeding due to atrioventricular continuity disruption, particularly in severe mitral annular calcification, is associated with high mortality.

Pressure-volume Loop

Volume Overloaded Lesions

Pathophysiological Stages

- Acute Phase

- Chronic Compensated Phase

- Chronic Decompensated Phase

Pathophysiology

- Chronic volume load leads to increased end-diastolic volume and eccentric hypertrophy to maintain forward stroke volume.

- Mitral and tricuspid regurgitation increase preload.

- Aortic and pulmonary regurgitation increase afterload, causing additional concentric hypertrophy.

- Prolonged volume overload may result in ventricular dysfunction and irreversible myocardial damage.

- Quantification of cardiac chamber size and function is crucial for management.

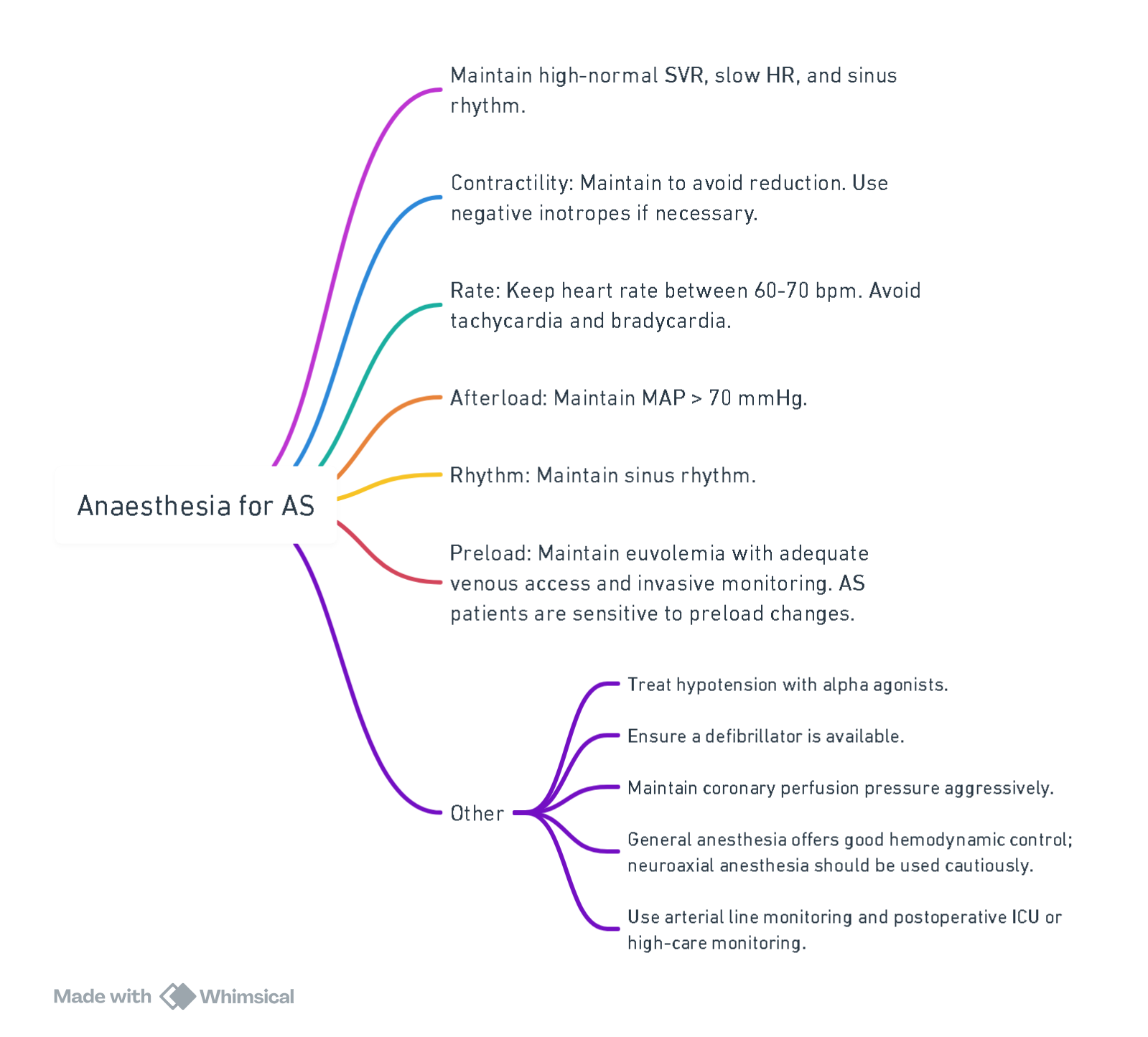

Aortic Regurgitation

Pathophysiology

- Etiologies:

- Genetic: Marfan syndrome, Ankylosing Spondylitis, Syphilis.

- Post-inflammatory: Endocarditis, Rheumatic Heart Disease.

- Congenital: Bicuspid aortic valve.

- Inflammatory cells: Damage valve cusps (e.g., Godpasture’s disease).

- Valve Abnormalities: Aortic root dilation, abnormal valve leaflets.

Mechanism

- Aortic Regurgitation:

- Blood flows back from the aorta to the LV during diastole.

- Turbulent backflow causes a diastolic, decrescendo murmur.

- Widened pulse pressure.

- S3 heart sound.

- Frank-Starling Compensation:

- LV dilation and eccentric hypertrophy to accommodate increased volume.

- Initially maintains normal cardiac output.

- Eventually leads to systolic heart failure due to myocardial weakening.

- Backward Failure: Increased LV end-diastolic pressure, pulmonary congestion, and diffuse crackles on auscultation.

Hemodynamic Consequences

- Acute AR poorly tolerated, leading to acute left heart failure and pulmonary edema.

- Chronic AR develops slowly with volume-loaded LV, eccentric hypertrophy, massive LV dilation, decreased LV function, increased LVEDP, increased LAP, and pulmonary congestion.

Clinical Findings

- Peripheral Diastolic Blood Pressure: Decreases due to backflow.

- Bounding Pulse: Rapid upstroke and downstroke.

- Pistol Shot Pulse: Sharp systolic sound over femoral arteries.

- De Musset’s Sign: Head bobbing with each systole.

- Angina on exertion: Due to decreased coronary artery perfusion.

- Fatigue: Low forward blood flow.

- Pulmonary Congestion: Dyspnea, PND, orthopnea.

Causes

- Rheumatic heart disease, infective endocarditis, systemic lupus erythematosus, calcification, congenital aorta, Marfan syndrome, syphilis, and aortic dissection.

- Dilatation of the aortic valve annulus or the aortic root, chronic hypertension.

Clinical History

- Heart failure symptoms.

Murmur

- Location: Left sternal border, 3rd/4th ICS.

- Timing: Early diastole.

- Duration: May last the entire diastole.

- Quality: Blowing, decrescendo.

Austin Flint Murmur

- Caused by severe regurgitation vibrations.

- Location: Apex.

- Timing: Mid-diastole.

- Quality: Rumbling.

Associations

- Water-Hammer Pulse

- Pulsating Organs

- De Musset: Head bobbing with pulse.

- Quinke’s Capillary: Pulsation in nail bed.

- Lighthouse Sign: Facial blanching/flushing.

- Muller’s Sign: Uvula pulsation.

- Becker’s Sign: Retinal artery pulsation.

- Gerhard’s Sign: Pulsation in spleen.

- Rosenbach’s Sign: Pulsation in liver.

- Wide Pulse Pressure

- Sounds

- Pistol Shot: Sharp sounds over femoral artery.

- Douzier’s Sign: Systolic and diastolic bruits over femoral artery.

- Sustained apical pulse and S3.

Special Investigations

ECG and CXR

- ECG: LV hypertrophy.

- CXR: LV hypertrophy.

Echo

- Defines mechanism of AR, severity, and repercussions.

- Regurgitant volumes:

- Mild: <20% of LV SV.

- Moderate: 20-40% of LV SV.

- Severe: >60% of LV SV.

Indications for Surgery

- Symptomatic patients.

- Asymptomatic patients with LV EF <50%.

- Asymptomatic patients with LV end-systolic dimension (LVESD) > 50mm.

- Aortic root dilation >55mm.

History

- Asymptomatic patients with normal LV function have a low incidence of adverse events.

- Once LVESD >50mm, the incidence of symptoms, LV dysfunction, and death is 19% per year.

- Symptoms of left heart failure include exercise intolerance, dyspnea, PND, and orthopnea. Angina is due to poor coronary perfusion, and palpitations are common.

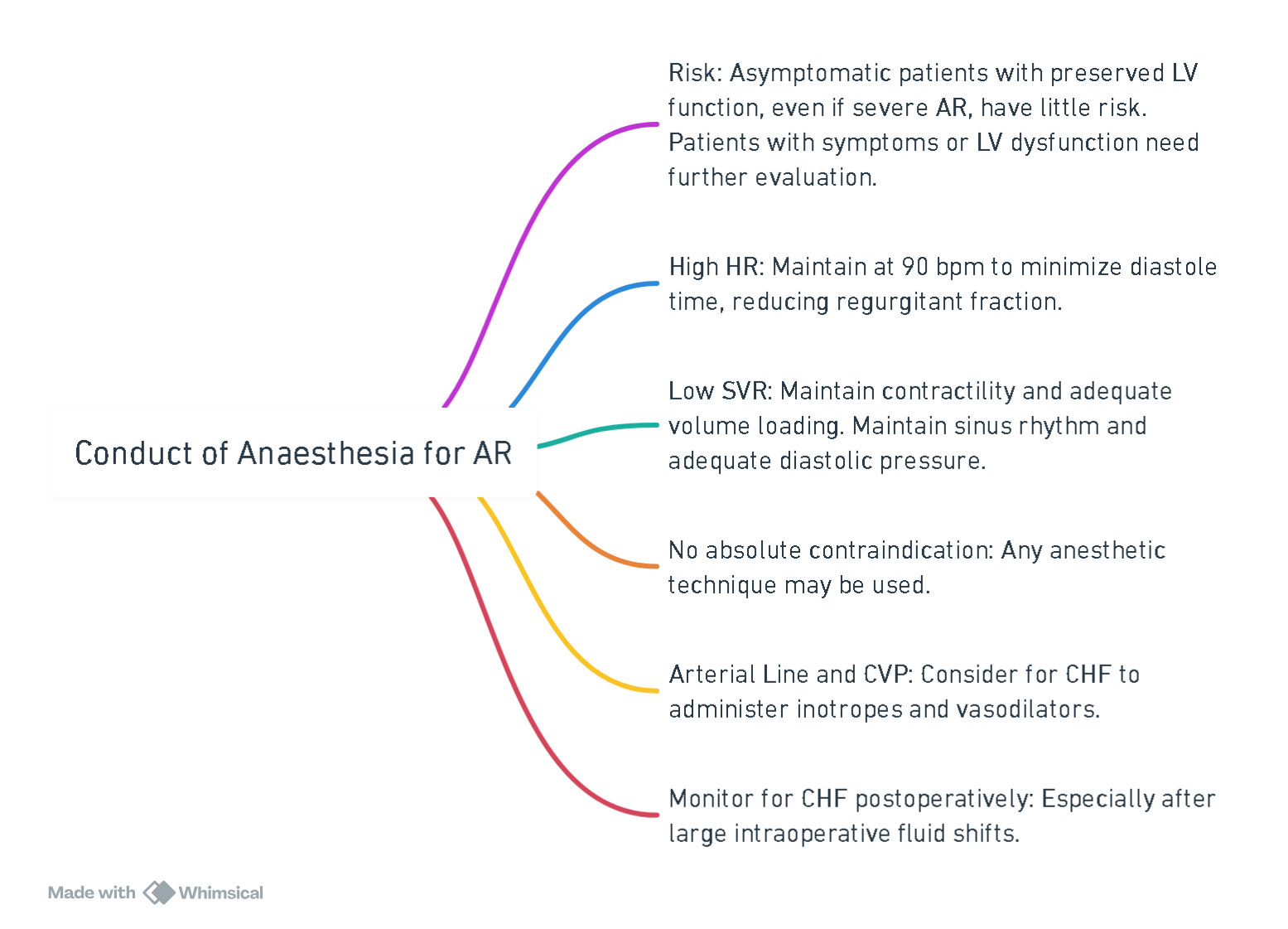

Anesthesia Management

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Overview of the Valve Lesion

Chronic Aortic Regurgitation

Severe chronic aortic regurgitation (AR) results in volume overload of the left ventricle (LV), causing gradual LV dilation and eccentric hypertrophy. While biventricular function typically remains intact in moderate to severe AR, advanced stages can lead to dilated cardiomyopathy and ultimate LV failure, characterized by a progressive decrease in ejection fraction, cardiac output (CO), and increased left atrial (LA) and pulmonary artery pressures. Severe chronic AR often presents with low diastolic blood pressure (BP) and wide pulse pressure, which is well tolerated unless accompanied by coronary artery disease.

Detailed discussions on the etiology, pathophysiology, stages of chronic AR severity, and surgical indications are available in:

- Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of chronic aortic regurgitation in adults

- Natural history and management of chronic aortic regurgitation in adults

Acute Aortic Regurgitation

Acute AR (e.g., due to aortic dissection or endocarditis) causes rapid volume overload of the relatively noncompliant LV, leading to increased LV end-diastolic and LA pressures and decreased coronary perfusion pressure. This can result in severe heart failure and cardiogenic shock, requiring initial intensive medical management and emergency cardiac surgical repair. Perioperative risk is high, and intraaortic balloon pump (IABP) use is contraindicated as it exacerbates LV dilation by increasing regurgitation across the aortic valve.

Preoperative Considerations

During the preanesthetic consultation and review of cardiac diagnostic studies, focus is placed on:

- Severity of AR

- Presence and severity of heart failure

- Associated aortic root dilation

- Aortic stenosis (AS)

- Pathology of other cardiac valves

Patients should be medically optimized before elective aortic valve surgery for chronic AR. Emergency surgery is required for acute severe AR, with temporary stabilization using IV vasodilators (e.g., nitroprusside) and possibly an inotropic agent (e.g., dobutamine) if there is a delay.

Heavy premedication is avoided in severe AR patients, though small incremental doses of short-acting IV benzodiazepine (e.g., midazolam 1 to 2 mg) may be administered for anxiolysis if necessary.

Prebypass Hemodynamic Management

- Sinus rhythm

- HR 80-100

- Low SVR

- Maintain Preload

- Augment contractility

Prebypass TEE Assessment

Chronic Aortic Regurgitation

Prior to CPB, TEE confirms AR presence and quantifies its severity. Severity estimation is done using color-flow Doppler to measure the largest jet width in the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), expressed as a percentage of LVOT width (mild AR ≤30%, severe AR ≥65%). The narrowest neck of the regurgitant jet (vena contracta) is measured, and continuous-wave Doppler imaging determines pressure half-time. Pulsed-wave Doppler imaging of the descending aorta identifies holodiastolic flow reversal.

The etiology of AR, measurements of the annulus and sinotubular junction, and aortic root geometry are assessed. Features suggesting successful repair include isolated cusp prolapse or aortic root dilation with normal cusp motion. The LV is examined for global dysfunction.

Acute Aortic Regurgitation

In acute AR cases, TEE confirms etiology (e.g., endocarditis, aortic dissection). Indicators include early mitral valve closure and non-holodiastolic flow reversal in the proximal descending aorta despite severe AR.

Procedure-Specific Considerations

Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR)

SAVR for symptomatic severe AR is performed via midline sternotomy or upper ministernotomy, followed by CPB establishment. Cardioplegia may be delivered directly into coronary ostia or retrograde via the coronary sinus due to regurgitant reflux. After achieving cardiac arrest, native valve leaflets are excised, the aortic annulus is measured, and the prosthetic valve is implanted. Removal of air from the ascending aorta and left heart chambers is ensured before weaning from CPB.

Surgical Aortic Valve Repair

Selected patients with severe AR may undergo aortic valve repair. Procedures involve standard CPB with cardiac arrest, followed by valve examination and repair, such as resuspension of a prolapsing leaflet or aortic root remodeling. Post-repair, de-airing and CPB weaning protocols are similar to SAVR.

Postbypass TEE Assessment

Post-SAVR TEE checks for normal prosthetic valve function. Significant paravalvular leaks or abnormal function require a return to CPB. For aortic valve repair, key indicators of recurrent postoperative AR risk include residual AR jet, leaflet coaptation length <4 mm, or a coaptation point below the aortic annulus level.

Postbypass Management

In severe AR, contractility is usually well-preserved, but inotropic agents may be needed during CPB weaning in cases of severe LV dilation and impaired function. Agents like milrinone or dobutamine (with inodilator properties) are used, counteracting excessive vasodilation with alpha-adrenergic agents like phenylephrine or norepinephrine. Other postbypass management aspects align with those for AVR in AS.

Pressure Volume Loop

Mitral Regurgitation

Pathophysiology

- Backflow of Blood: From the left ventricle to the left atrium due to impaired mitral valve closure.

- Increased Volume and Pressure in Left Atrium

- Volume Pushed Back into Left Ventricle

- Dilated Left Ventricle

- Forward Flow Decreased: Leads to pulmonary congestion.

Mechanism

- Left Ventricular Dilation: Displaces papillary muscles.

- Dilation of the Mitral Valve Annulus: Tethering of chordae tendineae.

- Mitral Valve Leaflets Flail: Structurally abnormal or weak valve.

- Fusion and Inflammation of Valve Leaflets: Leads to vegetations forming on valve leaflets.

Hemodynamic

- Left atrium exposed to volume and pressure increases, leading to dilation and atrial fibrillation.

- Left ventricle exposed to increased preload, leading to dilation and eccentric hypertrophy, gradual systolic failure.

- Once left atrial compliance is exceeded, LAP increases, PAP increases, right ventricle enlarges, and right ventricular dysfunction ensues.

Causes

- Valvular: Rheumatic heart disease, infective endocarditis, ruptured chordae tendineae, calcification.

- Cardiac: Myocardial infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Structural (Organic) MR: Rheumatic heart disease, connective tissue disorders, myxomatous disease, congenital.

- Functional MR: Ischemic heart disease.

Clinical Findings

- S3 Heart Sound

- Apical Impulse: Palpable and auscultable.

- Myocardial Remodelling: Decreased muscle efficiency.

- Congestive Heart Failure: Decreased oxygen saturation, tachypnea, crackles, frothy sputum if severe.

- Peripheral Edema: Due to activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and increased intravascular hydrostatic pressure.

- Holosystolic Murmur: Radiates to axilla, increases with afterload (e.g., making a fist).

Murmur

- Location: Apex, radiating to axilla and left scapula.

- Timing: Mid-systole.

- Quality: High frequency (sssssh).

- If only the posterior leaflet is affected, the murmur radiates to the LLSB up to the neck (similar to AS).

Associated

- S3, wide physiological split of S2.

- Cardiomegaly, left lower sternal border (LLSB) atrial enlargement.

- Atrial fibrillation.

Investigations

ECG

- Left atrial enlargement, atrial fibrillation.

CXR

- Left atrial and left ventricular enlargement.

Echo

- Assess the degree of regurgitation, left atrial enlargement, thrombus in left atrium, and evaluate for associated pulmonary hypertension in advanced disease.

History

- Commonly encountered valve lesion (1 in 5 adults).

- Measurement of ejection fraction is misleading, and systolic dysfunction is often underestimated.

Indications for Surgery

- LV EF < 60% or increase in LV end-systolic dimension > 40mm.

- Symptoms progress slowly over many years.

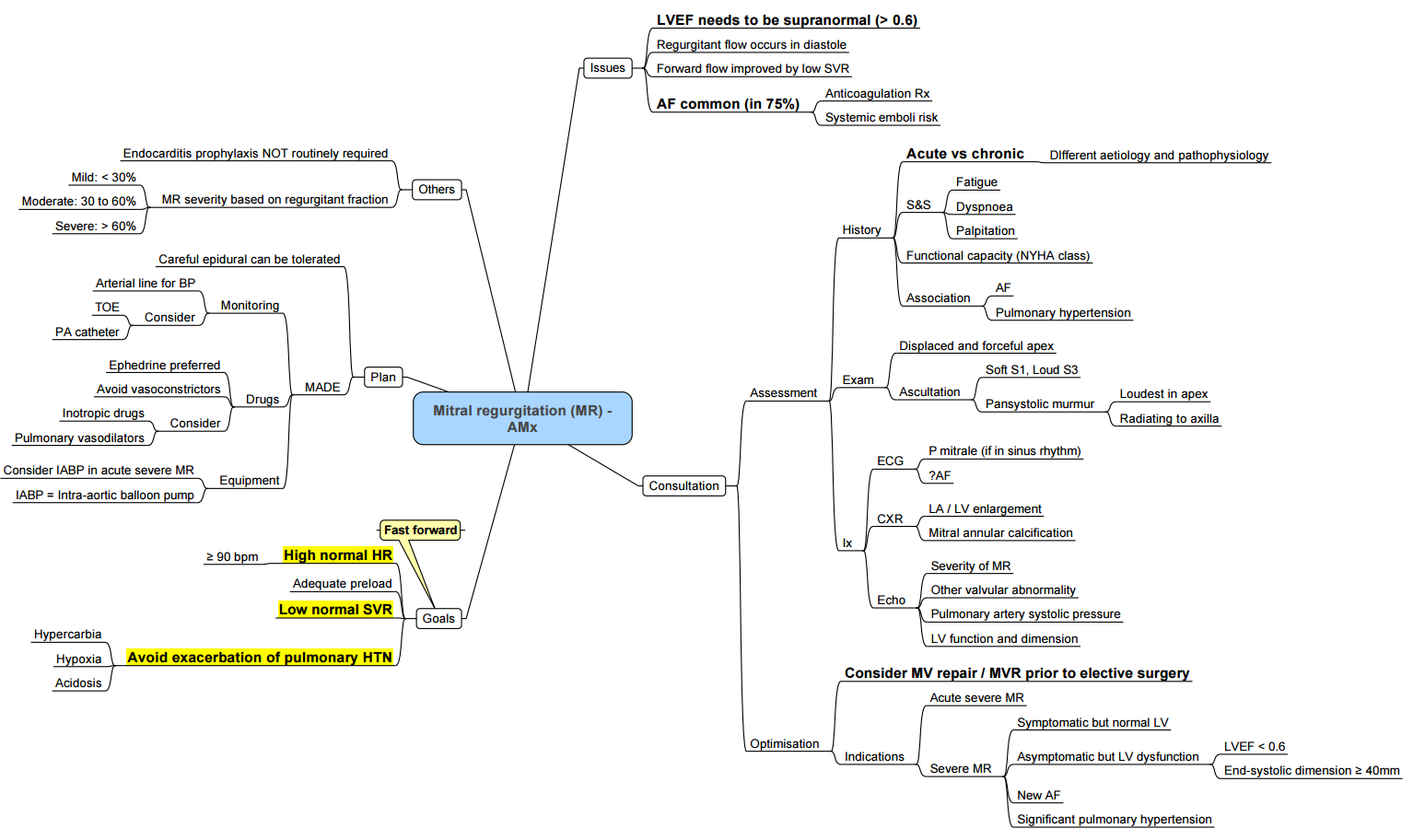

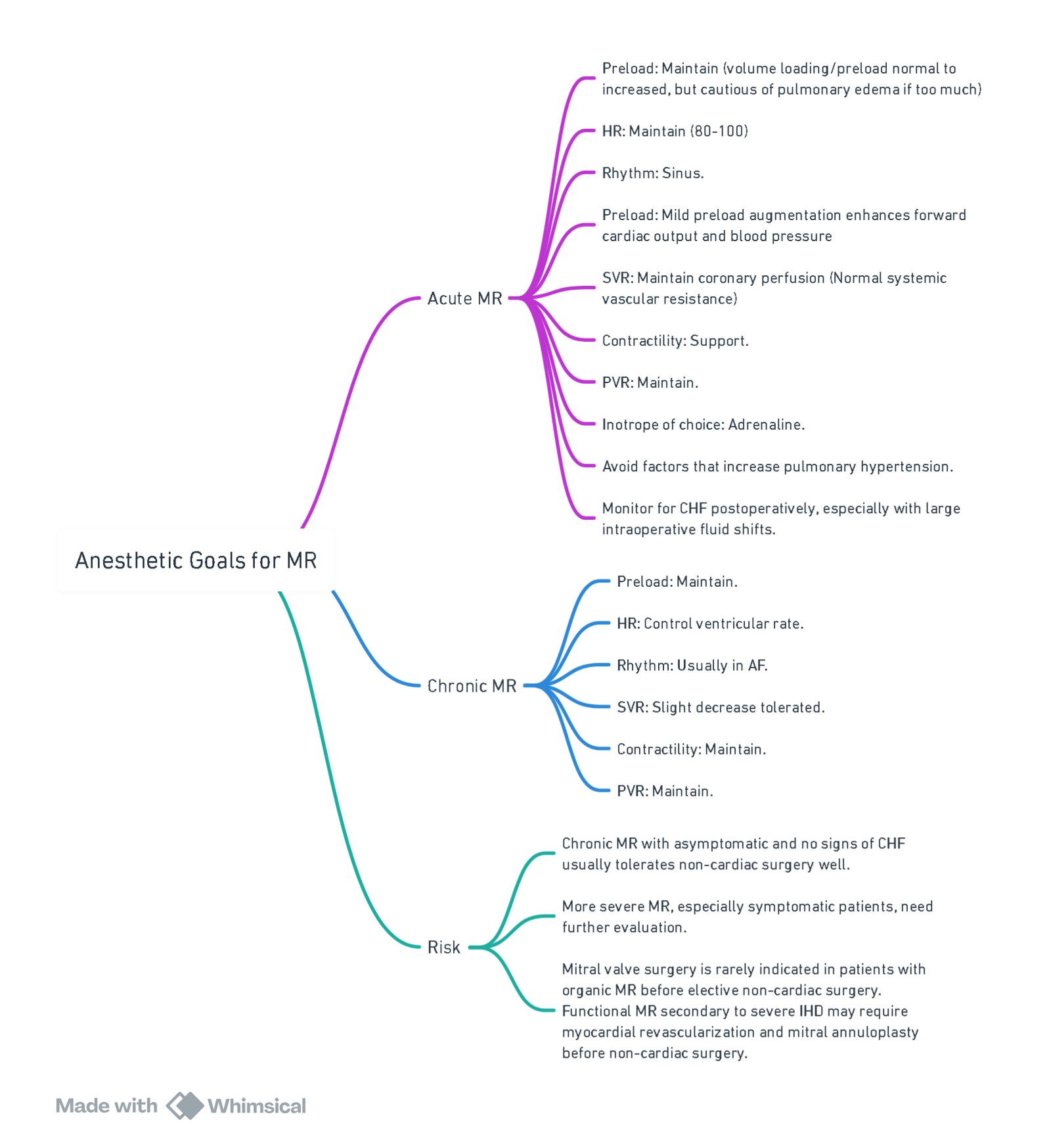

Anesthesia Management

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Overview of the Valve Lesion

Chronic Mitral Regurgitation

- Pathophysiology: Chronic mitral regurgitation (MR) leads to volume overload of the left atrium (LA) and left ventricle (LV), resulting in LA and LV enlargement, elevated LA pressure, and atrial dysrhythmias (typically atrial fibrillation). Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) and pulmonary artery pressure may be increased in severe cases.

- Primary Chronic MR: Involves disease of the mitral leaflets and supporting structures. Failure of leaflet coaptation occurs due to annular dilation, leaflet prolapse, or leaflet flail, often due to degenerative or rheumatic valve disease. Reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) indicates significant LV systolic dysfunction, leading to worse long-term outcomes.

- Secondary Chronic MR: Stems from underlying LV dysfunction (ischemic or non-ischemic), leading to mitral leaflet tethering or tenting, impaired valve closure, and annular enlargement. Surgical intervention may occur during other cardiac surgeries like coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Acute Mitral Regurgitation

- Causes: Acute MR can result from ruptured chordae, papillary muscle rupture, myocardial infarction, or rapid onset cardiomyopathy. Acute MR leads to a sudden increase in LA pressure, causing flash pulmonary edema, acute right heart failure, or cardiogenic shock.

- Treatment: Requires intensive medical stabilization and often urgent or emergency surgical repair. For acute ischemic MR, percutaneous coronary revascularization may resolve MR without valve intervention. Intraaortic balloon pump (IABP) insertion preoperatively may help by reducing LV afterload and increasing diastolic coronary blood flow.

Preoperative Considerations

- Evaluation: Focuses on MR severity, heart failure presence, mitral stenosis (MS), other cardiac valve pathology, and LV function. Advanced cases may show pulmonary edema and right heart enlargement on chest radiograph (CXR). Patients should be optimized before elective surgery for chronic MR.

- Medications: Many patients with severe MR and AF are on chronic anticoagulation therapy, which requires careful management preoperatively.

Prebypass Hemodynamic Management

- Goals: Similar to those for aortic regurgitation (AR). Special considerations apply to secondary MR due to ischemic heart disease. Detailed management strategies are provided in separate topics on intraoperative hemodynamic management of valve disease.

Prebypass TEE Assessment

Chronic Mitral Regurgitation

- Focus: Mechanism of MR, repair feasibility, MR severity, and LV/RV function. Color-flow Doppler assesses regurgitant jet size, and proximal isovelocity surface area (PISA) method helps quantify effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) or regurgitant volume.

- Challenges: Severity is often underestimated under anesthesia due to reduced sympathetic tone and LV afterload. Hemodynamic conditions should approximate preoperative baseline for accurate assessment.

- Mitral Valve Structure: Includes anterior and posterior leaflets, papillary muscles, chordae tendineae, and mitral valve annulus. Intraoperative 3D TEE can provide detailed valve morphology and annular size.

Acute Mitral Regurgitation

- Assessment: Mechanism of MR, repair feasibility, hemodynamics, LV/RV function, and MR severity. Acute MR may show lower jet velocity, smaller jet area, and eccentric jets, complicating severity estimation.

Procedure-Specific Considerations

Surgical Mitral Valve Repair or Replacement

- Approach: Typically via midline sternotomy, CPB, and LA entry. Bicaval venous cannulation is recommended for adequate venous drainage. Choice between bioprosthetic or mechanical mitral valve is discussed in separate topics.

- Minimally Invasive Techniques: Small right thoracotomy with or without CPB, often using robotic technology. External defibrillator pads are important due to lack of immediate heart access.

Postbypass TEE Assessment

- Mitral Valve Repair: Assess residual MR and identify causes (e.g., inadequate repair, paravalvular leak). Evaluate SAM or LVOT obstruction. Normalize BP before final decisions.

- Mitral Valve Replacement: Check for paravalvular leaks, abnormal prosthetic leaflet mobility, or high gradients.

Postbypass Management

- Hemodynamic Correction: Restore to baseline levels to reduce MR underestimation. Inotropic support may be necessary for LV impairment. Inodilator agents like milrinone may be used with norepinephrine to avoid vasodilation. IABP can assist in severe LV dysfunction.

- Right Heart Failure: Manage acute refractory right heart failure with high PVR using detailed strategies provided in related topics.

- Arrhythmias: Common postbypass, particularly AF. Treatment includes synchronized cardioversion and administration of amiodarone. Maintain high-normal potassium and magnesium levels.

- Bleeding: Common complication, managed through protocols for achieving hemostasis after CPB. Rarely, severe bleeding due to atrioventricular disruption may occur, especially in severe mitral annular calcification cases.

Pressure Volume Loop

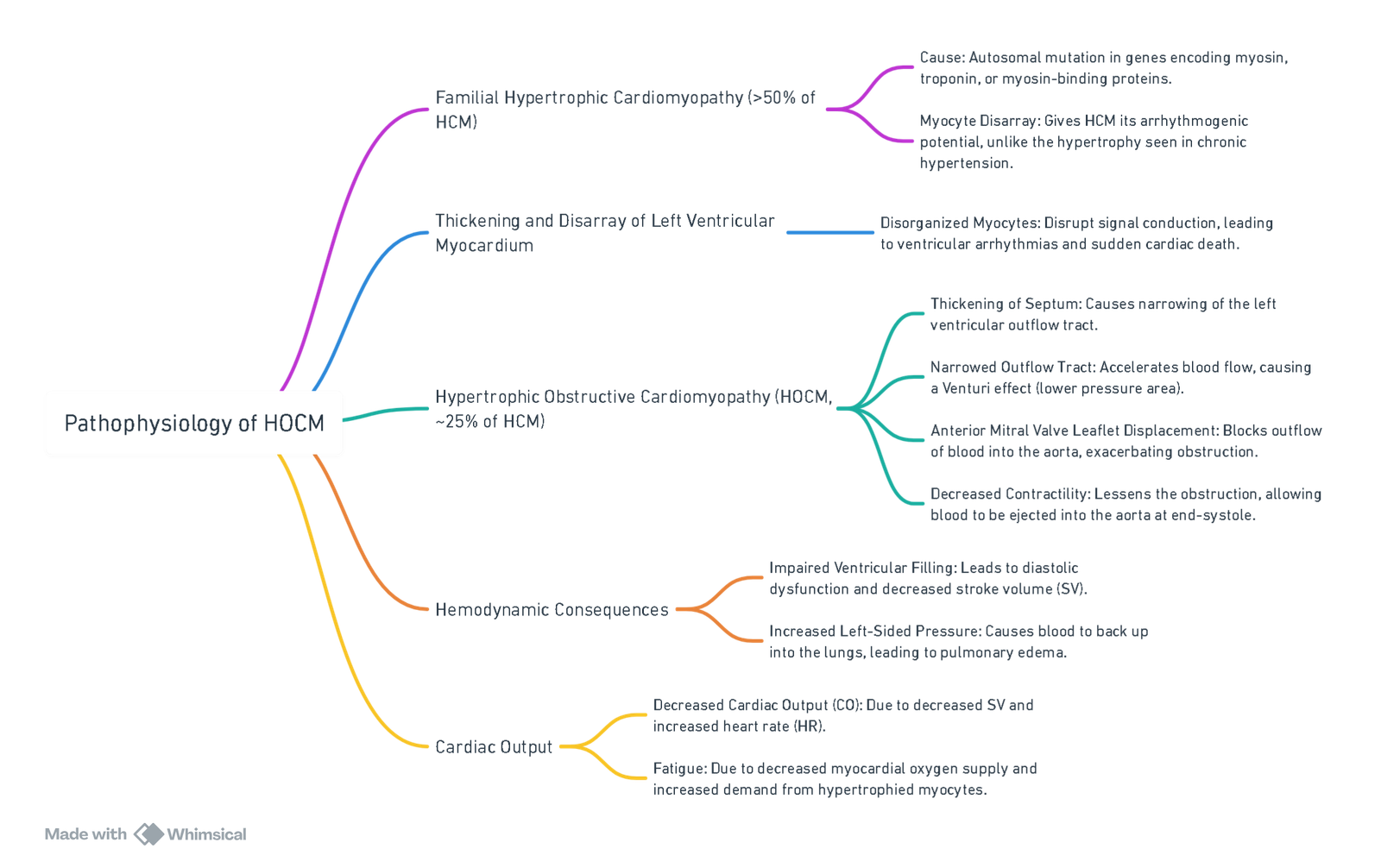

Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

Pathophysiology

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Clinical Findings

Signs/Symptoms/Lab Findings

- S4 Heart Sound: Audible in sinus rhythm due to atrial “kick” into the stiff ventricle.

- Systolic Murmur: Accentuated by Valsalva maneuver.

- Double-Tap or “Bifid” Pulse: Notable on physical examination.

Murmur

- Location: Broad apical pattern (LLSB to apex).

- Timing: Mid-systole.

- Quality: Harsh.

Associations

- Sustained apical pulse and S4.

- Hyperkinetic arterial pulse.

- Murmur increases with maneuvers that decrease venous return (Valsalva, squatting to standing).

Pulmonary Symptoms

- Diffuse Crackles on Auscultation: Indicates pulmonary congestion.

- Increased Airflow Resistance: Leads to increased work of breathing and stimulus to breathe.

- Dyspnea: Difficulty breathing.

- Tachypnea: Rapid breathing.

Anginal Chest Pain

- Coronary Artery Perfusion: Decreased due to tissue hypoxia, leading to angina.

Complications

- Ventricular Arrhythmias: Can lead to sudden cardiac death.

Differentiating Aortic Stenosis from HOCM

- Aortic Stenosis:

- Carotid pulse: Pulsus parvus et tardus.

- S2: Soft.

- Murmur during extrasystole: Softer, then louder on the next beat.

- Murmur on standing: Softer.

- Murmur intensity with squatting: No change.

- HOCM:

- Carotid pulse: Pulsus bisferiens.

- S2: Loud, clear.

- Murmur during extrasystole: Louder.

- Murmur on standing: Louder.

- Murmur intensity with squatting: Softer.

Anesthetic Management for HOCM

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

HOCM in Pregnancy

- HOCM: Depends on a well-filled LV to maintain output and decrease dynamic obstruction.

- Pregnancy: Exacerbates obstruction with increased HR, contractility, decreased SVR, aortocaval compression.

- Chronic β Blockade: Continued throughout pregnancy.

- Preferred Delivery Mode: NVD; tolerate second stage well due to increase in SVR.

Goals

- Maintain intravascular volume and venous return.

- Maintain SVR.

- Slow HR, sinus rhythm.

- Aggressively treat tachyarrhythmias.

- Prevent increases in myocardial contractility.

Anesthetic Management

- Avoid single shot spinal.

- Invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

- Slow graded epidural and combined spinal epidural with intrathecal opioid.

- Labor analgesia with epidural: Reduces catecholamine release.

- Preferred vasopressor: Phenylephrine.

- Avoid ephedrine: Potentially increases myocardial contractility.

- Postpartum diuresis: Prevent worsening outflow tract obstruction.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Acquired valvular heart disease increases the risk of infective endocarditis (IE). However, prophylaxis is no longer recommended solely based on increased lifetime risk. It is no longer recommended for patients with mitral valve prolapse or other valvular diseases without previous IE history.

Pericardial disease

Links

- Cardiac surgery

- Cardiac physiology

- Anaesthetic management of specific cardiac conditions

- Cardiac for non-cardiac surgery

- Pulmonary Hypertension

References:

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- Holmes, K. P., Gibbison, B., & Vohra, H. A. (2017). Mitral valve and mitral valve disease. BJA Education, 17(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkw032

- Valvular Heart Disease & Non Cardiac Anaesthesia: Dr S Fischer. Wits refresher 2013

- Up-to-date. Anesthesia for cardiac valve surgery. Retrieved June 5, 2024. Available at: Link.

- Paul A, Das S. Valvular heart disease and anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2017 Sep;61(9):721-727. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_378_17. PMID: 28970630; PMCID: PMC5613597.

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- ICU One Pager. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://onepagericu.com/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

AR

AS

MR

MS

HOCM

TR

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “f7f01689-fa3f-4a89-b53b-69efd29e2496”