- Aetiologies of Intraoperative Emboli

- Thrombo-embolism (PE)

{}

Aetiologies of Intraoperative Emboli

Pre-morbid Conditions

- Venous thrombosis

- Arterial thrombosis

- Fat emboli (trauma)

- Vegetation

Anaesthetic/Operative

- Anaesthetic:

- Air, oxygen (e.g., CVC insertion)

- Cannula fragments

- Aggregated blood product

- Drug aggregates

- Surgical:

- Carbon dioxide (insufflation)

Surgical Procedure

- Gas (e.g., liver surgery, venous injury)

- Amniotic fluid

- Fat

- Bone marrow (reaming)

- Tumour

Thrombo-embolism (PE)

Summary

Intraoperative Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Introduction

- Intraoperative pulmonary embolism often presents with hemodynamic instability and carries a high likelihood of rapid progression to death within a few hours.

- There is a five-fold increase in the incidence of PE perioperatively due to patient-specific risk factors, surgery-specific factors such as the inflammatory response, coagulation cascade, immobilization, and venous stasis resulting from surgical interventions.

Pulmonary Embolism: Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

Virchow’s Triad

- Hypercoagulable State

- Venous Stasis

- Vessel Injury

Pathogenesis

-

Development of Blood Clot:

- Commonly in deep veins of the legs, leading to Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) (95% of PE cases).

- Diagnosis: Ultrasound showing the presence of a clot in a deep vein of the leg.

-

Clot Dislodgement and Migration:

- The clot migrates to the inferior vena cava (IVC), right atrium, right ventricle, and lodges in the pulmonary arteries/arterioles, causing Pulmonary Embolism (PE).

-

Clot Breakdown Attempt:

- Lab Test: Positive D-Dimer (used when clinical suspicion of PE is low, based on Well’s Criteria).

- Fibrinogen breakdown products in blood.

Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

- Blockage of Pulmonary Vasculature:

- Decreased perfusion to lung parenchyma.

- Clot occludes pulmonary arteries/arterioles.

- Blood from the RV cannot pass the clot, leading to increased pulmonary and RV pressure (RV strain).

- Lab Tests: Increased troponin, lactate, BNP.

- Blood Pressure: Hypotension.

- Imaging: Echo shows increased RV size and decreased function, CTPA shows filling defect.

- ECG: S1Q3T3 pattern (McGinn-White sign).

Clinical Findings

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath):

- Ischemia of lung tissue distal to the clot.

- Pleuritic Chest Pain: Worsens during breathing.

- X-Ray: Usually normal, but can show Hampton’s Hump (increased opacity in pleural-based area, rare but specific sign of PE).

- Airflow/ventilation to lungs unaffected.

- V/Q Scan: Shows ventilation-perfusion mismatch.

- Chemoreceptors detect increased CO₂ and decreased O₂.

- Signal brain to increase breathing rate.

- Tachypnea (rapid breathing).

- Ischemia of lung tissue distal to the clot.

Pathophysiology

-

Thrombo-emboli Lodgment:

- Thrombo-emboli originating in the venous system typically lodge in a vessel smaller than the embolus, usually a pulmonary vessel, leading to respiratory function abnormalities and pulmonary gas exchange issues.

-

Respiratory Impact:

- Depending on the embolic size and load, there can be varying degrees of increased alveolar dead space, right-to-left shunting, and V/Q mismatch. Overperfusion of remaining perfused lung parenchyma may cause edema, alveolar hemorrhage, and atelectasis.

-

Hypoxia:

- Hypoxia can be exacerbated by a patent foramen ovale, leading to elevated right atrial pressures and increased right-to-left shunt fraction.

-

Circulatory Changes:

- Increased pulmonary vascular resistance from the emboli, hypoxia-mediated vasoconstriction, and vasoconstrictors like serotonin and platelet-activating factor cause acute rises in right ventricular (RV) and atrial pressures.

- Acute RV pressure and volume increases are poorly tolerated due to RV geometry and wall thickness.

-

Right Ventricular Failure:

- Significant drops in RV stroke volume and septal shift into the left ventricle compromise left ventricular preload.

- Decreased cardiac output leads to catecholamine-induced vasoconstriction and tachycardia, attempting to maintain cardiac output.

- Increased RV preload can lead to RV dilatation and further septal shift, further compromising left ventricular filling. Continued RV afterload increase and dilatation result in relative ischemia and failure, decreasing cardiac output.

Risk Factors

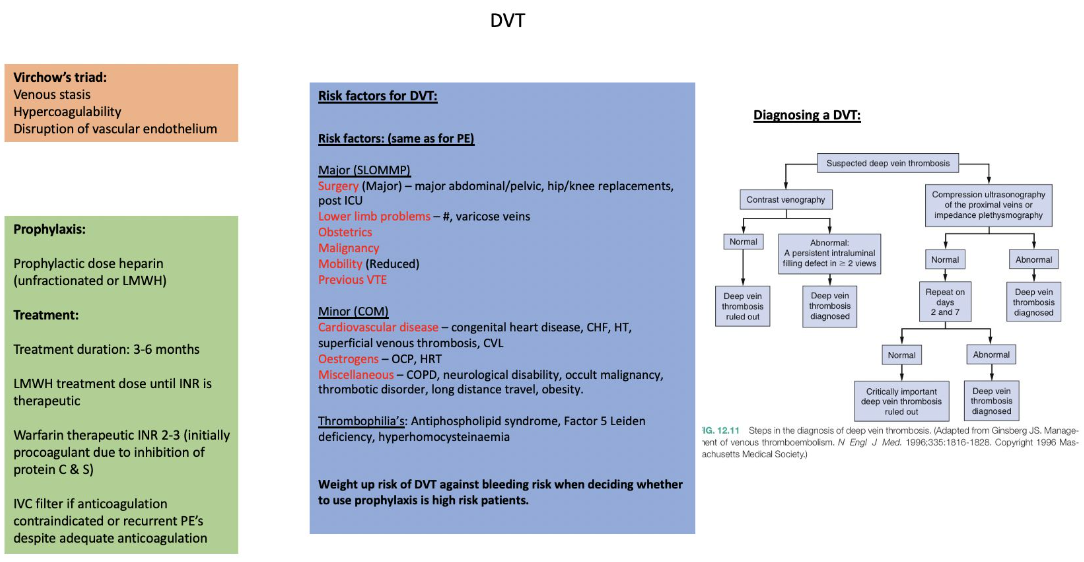

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT): Pathogenesis and Complications

Pathogenesis

- Virchow’s Triad:

- Hypercoagulable State:

- Abnormal release of coagulation-promoting cytokines (e.g., malignancy), increased clot formation (platelet activation), congenital coagulation defects (inherited disorders), estrogen (pregnancy, OCP), physical inactivity (obesity).

- Venous Stasis:

- Low blood flow rate at the site of vessel injury, decreased muscle motion, leading to decreased venous blood flow.

- Vessel Injury:

- Exposure of tissue factor on damaged cells and subendothelium for vWF binding.

- Hypercoagulable State:

Complications

- Clot Formation in Leg Veins:

- Deep, large veins allow for blood pooling (stasis, hypercoagulability).

- Venous return from legs often against gravity, with valves prone to backflow.

- Clot Embolization to Lungs:

- Can cause Pulmonary Embolism (acute life-threatening complication).

- Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism

- Hereditary:

- Antithrombin deficiency, Protein S deficiency, Protein C deficiency, Factor V Leiden, Prothrombin gene deficiency.

- Medical Interventions:

- Central venous catheterization, heparins, hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptives, chemotherapy, antipsychotics.

- Surgery:

- Major surgery, hip or leg fractures, hip or knee replacements, general anesthesia (compared to epidural/spinal for lower abdominal or lower extremity surgery).

- Acquired:

- Advanced age, cancer, reduced mobility, acute medical illness, inflammatory bowel disease, nephrotic syndrome, pregnancy/postpartum period, trauma, spinal cord injury, obesity, previous thromboembolism, tobacco use.

Anaesthesia and Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

- The incidence of PE is reduced with regional anaesthesia compared to general anaesthesia (GA).

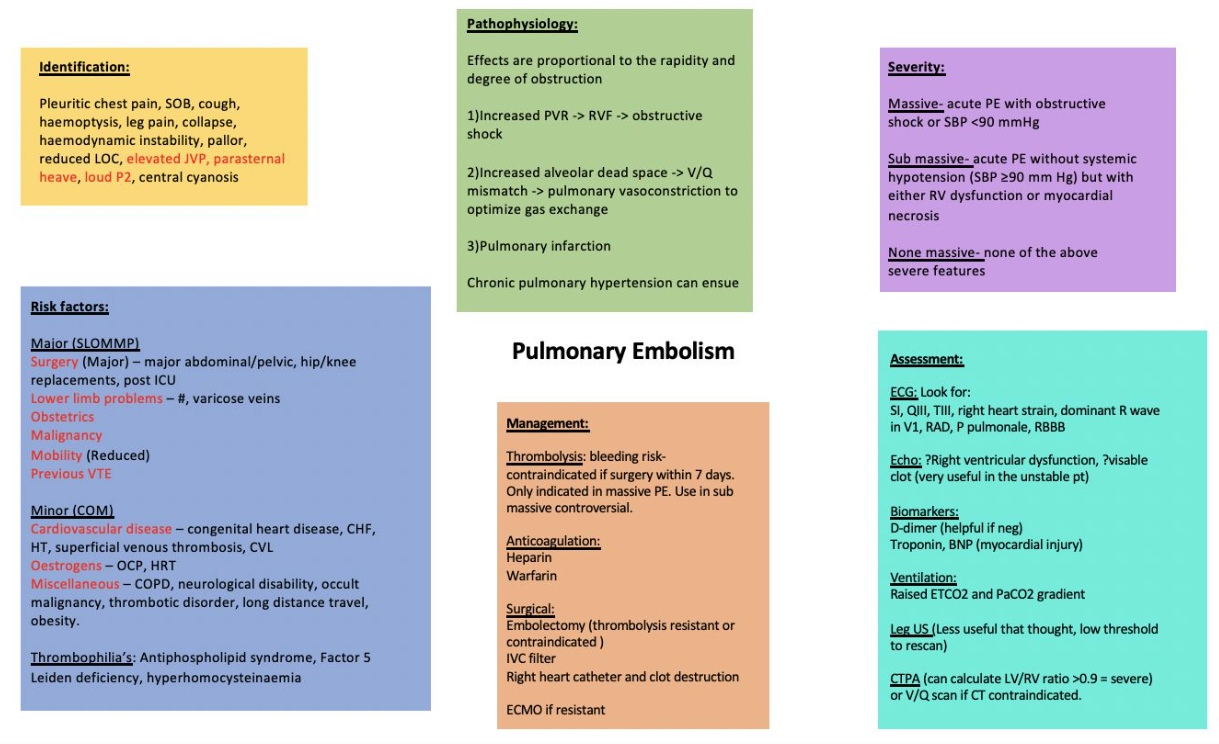

Diagnosis

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

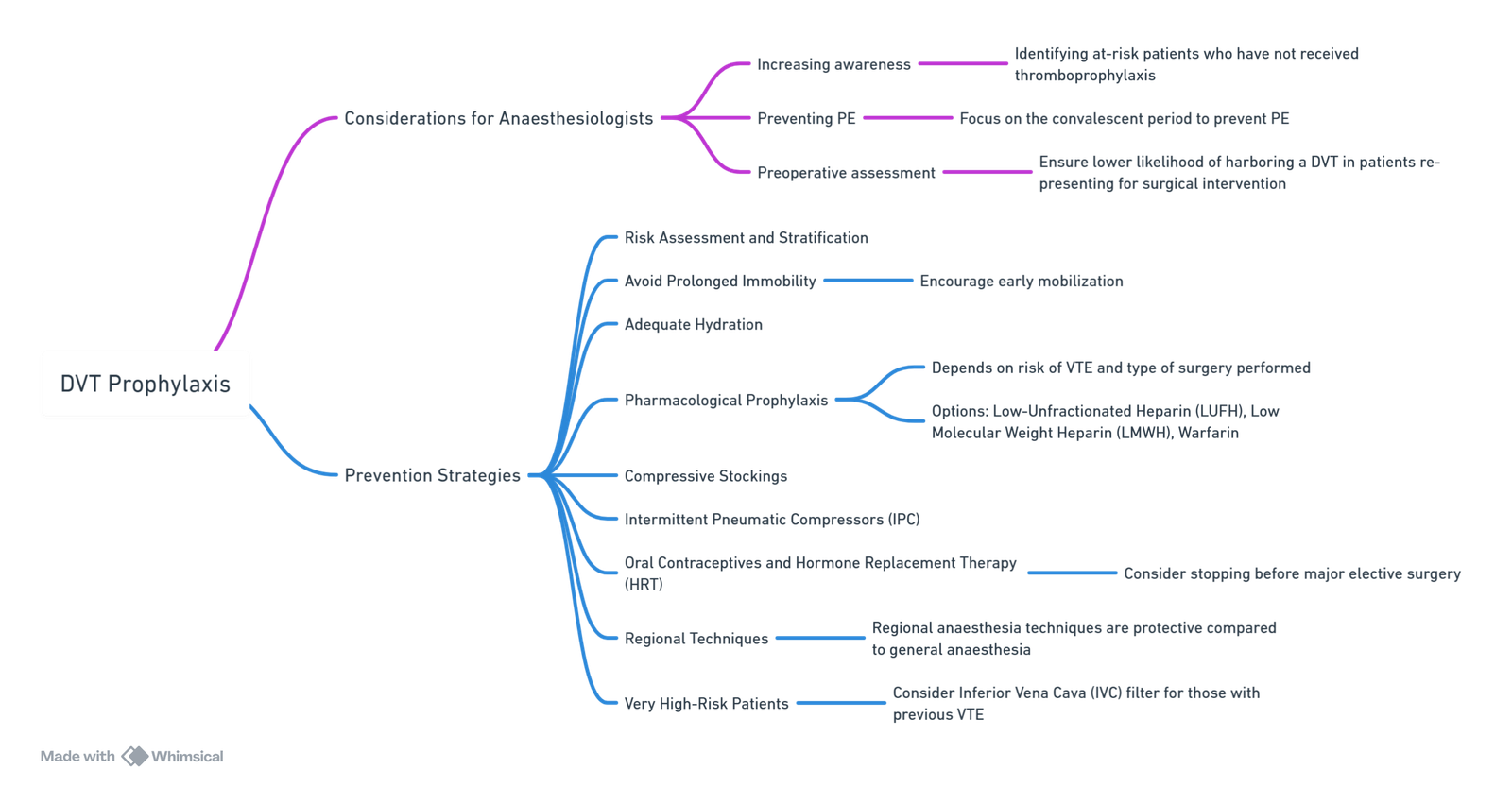

DVT Prevention

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Management of Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Anticoagulation

Initial Treatment

- Subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is recommended by the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) for the initial treatment of acute, non-massive PE.

- Unfractionated heparin (UFH) infusions are preferred intraoperatively or immediately postoperatively due to their shorter duration of action, quick titratability, predictable absorption, and rapid reversibility. This approach maintains the option for thrombolysis if required.

Anticoagulant Treatment for Acute Pulmonary Embolism

Drugs and Dosages

- Intravenous Unfractionated Heparin (IV UFH)

- Bolus: 80 U/kg or 5000 U

- Infusion: 18 U/kg/hr or 1300 U/hr

- Subcutaneous Unfractionated Heparin (SC UFH) (unmonitored)

- Bolus: 333 U/kg

- Maintenance: 250 U/kg twice daily

- Subcutaneous Low Molecular Weight Heparin (SC LMWH)

- Enoxaparin: 1 mg/kg twice daily

- Dalteparin: 100 IU/kg twice daily

- Tinzaparin: 175 IU/kg once daily

- Subcutaneous Fondaparinux

- <50 kg: 5 mg daily

- 50-100 kg: 7.5 mg daily

- More than 100 kg: 10 mg daily

- Warfarin

- Transition to warfarin when the patient is stable on oral medication.

Thrombolysis, Vena Cava Filter, and Embolectomy

Thrombolysis

- The risk of bleeding, particularly intracranial hemorrhage (up to 3%), limits the use of thrombolysis in the setting of operative intervention.

- A 2006 review indicated no clear benefit of thrombolytic therapy compared to heparin in treating acute PE.

- The ACCP guideline recommends against thrombolysis for most patients but suggests it for those with hemodynamic compromise and low bleeding risk.

Vena Cava Filters

- Vena cava filters are not used for PE treatment but may be considered when the risk of anticoagulation is too high. Anticoagulation should commence as soon as it is safely possible post-filter placement.

Surgical Embolectomy

- Indicated for patients with hemodynamic compromise who fail or have contraindications to thrombolysis.

Catheter-directed Intervention

- Includes suction embolectomy or catheter-directed thrombolysis.

- Not well studied and may be unavailable in many centers.

- Important for perioperative patients who are hemodynamically unstable.

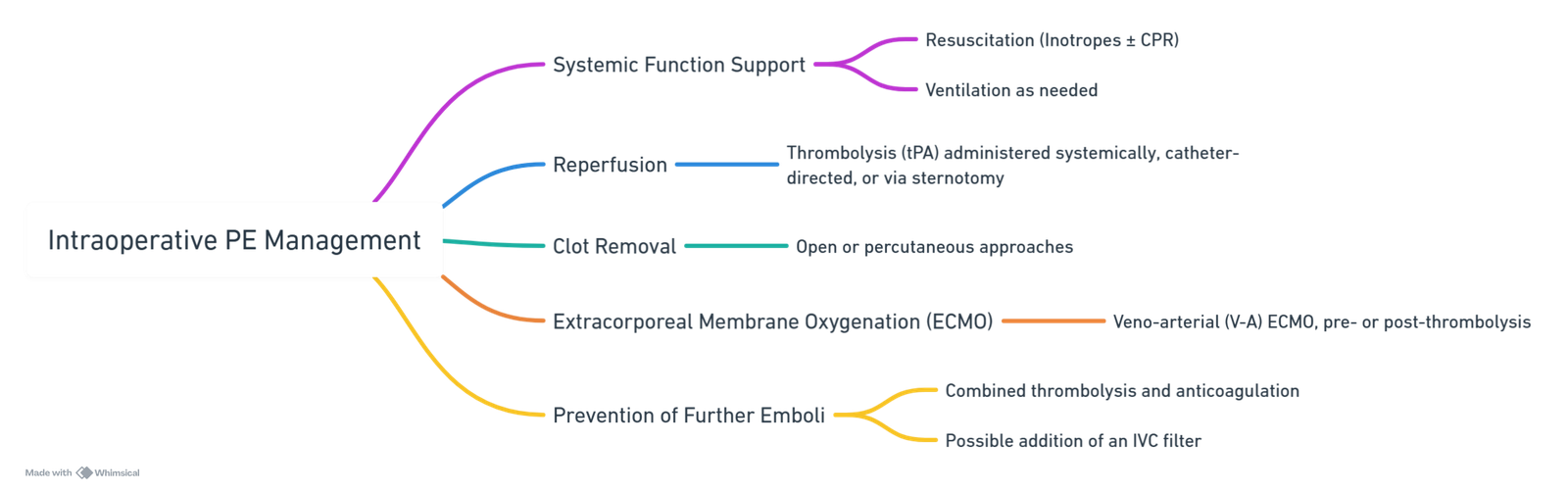

Summary of Management of Intraoperative PE

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Complications of Pulmonary Embolism

Acute/Massive PE

- RV Afterload

- ↑ RV pressure and expansion

- Leftward shift of ventricular septum

- ↓ Left ventricle filling in diastole

- ↓ Cardiac output

- Obstructive Shock: Impaired heart filling

- Pulseless Electrical Activity: ECG activity in absence of palpable pulse

- ↑ RV pressure and expansion

- Lung Infarction (tissue death from ischemia)

- Inflammatory cells migrate to site and release cytokines

- ↑ Permeability of blood vessels

- Permeability-driven (exudate) fluid leakage into pleural space

- Pleural Effusion

- Failure to oxygenate blood

- Type I Respiratory Failure: Hypoxemic; ↓ blood O₂

- Type II Respiratory Failure: Hypercapnic; ↑ blood CO₂

- Failure to ventilate

Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension (CTEPH) (<5% of PE cases)

- Unresolved clot after 2 years leading to fibrosis of pulmonary vasculature

- Chronic ↑ RV afterload

- ↑ Stretching of myocytes causing RV hypertrophy and dilation

- ↓ RV ejection fraction

- Right Heart Failure (“Cor Pulmonale”)

- Chronic ↑ RV afterload

Air Embolism

Overview

- Vascular air or gas embolism occurs when air (or other exogenous gas) is entrained from the operative field or another communication with the environment into the venous or arterial vasculature, leading to systemic effects.

- Gravitational gradient is not the sole factor for vascular air emboli. Gas under pressure within the peritoneal cavity or via vascular access significantly contributes to this phenomenon, requiring anaesthesiologists to be vigilant about VAE aetiologies, prevention, morbidity, diagnostic considerations, and treatment options.

Pathophysiology

- Morbidity and mortality of VAE are primarily determined by the volume of air entrained and the rate of accumulation.

- Lethal volume in adults: 200-300 ml or 3-5 ml/kg.

- Proximity to the right heart: The closer the vein of entrainment to the right heart, the smaller the required lethal volume.

- The lung vasculature acts as an effective filter for foreign matter in the circulation. Slow entrainment rates may allow large air volumes to be removed by the lung “filter,” causing mild to moderate symptoms in awake patients.

- Entrainment volume and rate depend on variables described in the Hagen–Poiseuille equation. Key determinants include the vessel/cannula luminal radius and pressure gradient (negative pressure from respiration, positive pressure from gravitational force, or exogenous mechanical forces like endoscopic equipment).

- The pathophysiologic response depends on the gas volume in the right ventricle:

- Large volumes (5 ml/kg): Can cause an effective gas air-lock, leading to complete outflow obstruction from the right ventricle, acute right heart failure, and cardiovascular collapse.

- Modest volumes: May cause partial air-locks, resulting in decreased cardiac output, hypotension, myocardial and cerebral ischemia, and potentially death.

- Air in pulmonary vasculature: Can lead to pulmonary vasoconstriction, bronchoconstriction, release of inflammatory mediators, and V/Q mismatch even without affecting cardiac output.

Clinical Manifestations

- Gasping for air can decrease intrathoracic pressure and increase gas entrainment.

- Pulmonary signs of VAE: Crackles, wheezing, tachypnea.

- In anaesthetised patients: Sudden drop in ETCO₂ and arterial oxygen saturation, ABG shows decreased oxygen tension and hypercapnia, indicating “dead space” ventilation.

Aetiology

- The at-risk population now includes a variety of surgical interventions using gas under positive pressure, in addition to those related to specific patient positions or procedures involving gravitational/atmospheric pressure and exposed venous plexuses.

- Reported incidences:

- Up to 100% for classical sitting position craniotomy

- 50% during caesarean section and laparoscopic surgery

- 20% during hip arthroplasty

- Requirements for VAE:

- A source of gas

- Communication between the gas source and the venous system

- A pressure gradient enabling gas ingress

Common Procedures and risk

| Procedure | Relative Risk* |

|---|---|

| Sitting position craniotomy | High |

| Posterior fossa/neck surgery | High |

| Laparoscopic procedures | High |

| Total hip arthroplasty | High |

| Caesarean delivery | High |

| Central venous access – placement/removal | High |

| Craniosynostosis repair | High |

| Spinal fusion | Medium |

| Cervical laminectomy | Medium |

| Prostatectomy | Medium |

| Gastrointestinal endoscopy | Medium |

| Contrast radiography | Medium |

| Coronary surgery | Medium |

| Anterior neck surgery | Low |

| Vaginal procedures | Low |

| Hepatic surgery | Low |

Approximate expected reported incidences: high > 25%; medium 5 – 25%; low < 5%

Diagnosis

Venous Air Embolism

- Symptoms:

- Tachypnea → Hypoxia → Apnea

- Tachycardia → Hypotension → Cardiovascular collapse

- Light-headedness → Altered mental status

- ↓ EtCO₂, ↓ PaO₂

- ECG: Tachyarrhythmias, AV block, RV strain, ST elevation/depression, T-wave changes

Arterial Air Embolism

- Manifestations include Myocardial Infarction (MI) or Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA).

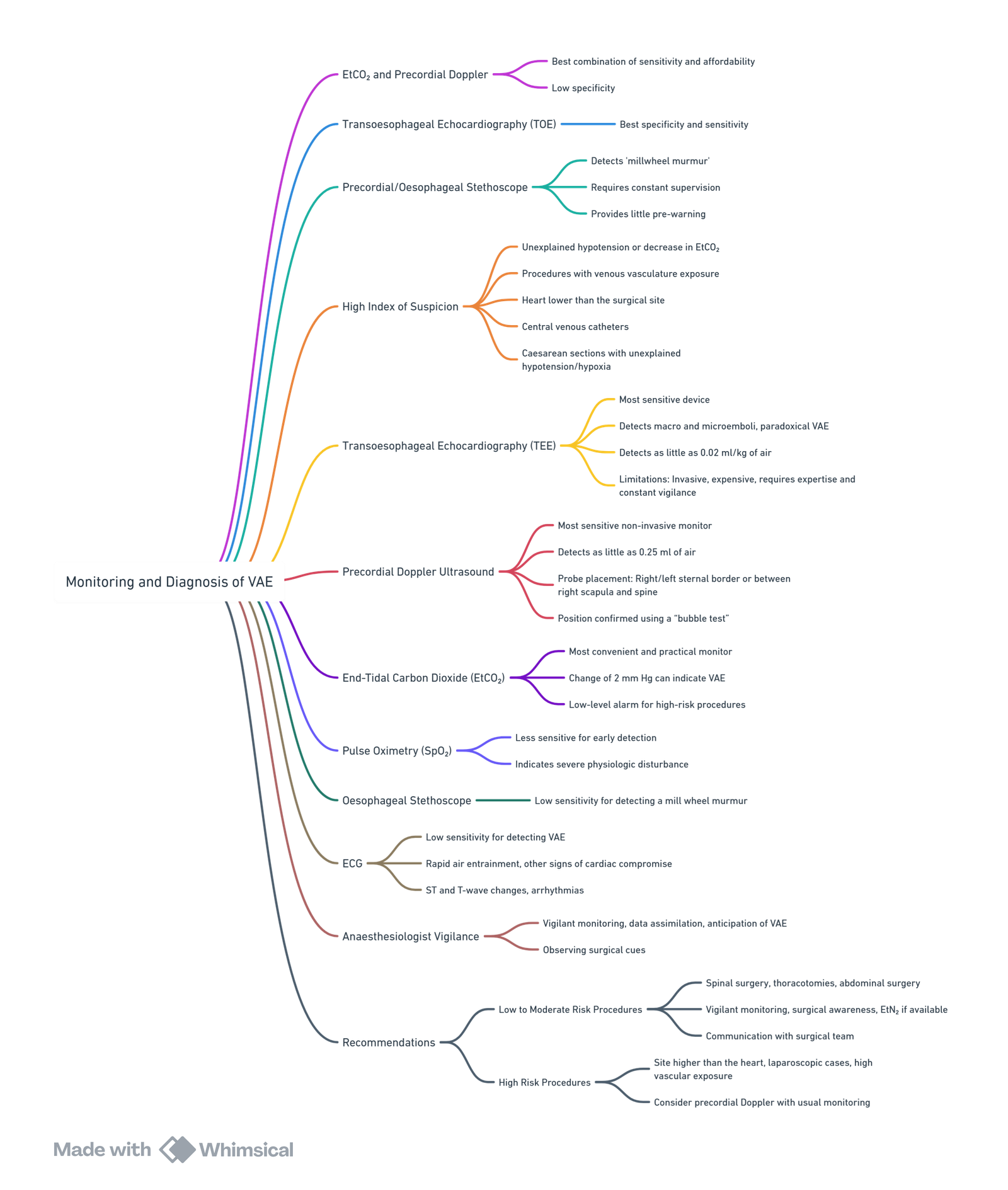

Monitoring and Diagnosis

- EtCO₂ and Precordial Doppler: Offer the best combination of sensitivity and affordability, though they have low specificity.

- Transoesophageal Echocardiography (TOE): Best specificity and sensitivity.

- Precordial/Oesophageal Stethoscope: Detects ‘millwheel murmur’; requires constant supervision and provides little pre-warning.

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Prevention of Venous Air Embolism (VAE)

Standard Monitoring in Anaesthesia

Standard Practices

- Patient Positioning: Ensure optimal positioning to minimize risk.

- Hydration: Maintain adequate hydration to support hemodynamic stability.

- Visual Inspection: Regular visual checks for signs of VAE.

- Hemodynamic Monitoring: Continuous monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate.

- Oxygen Saturation (SpO₂): Monitor to detect early signs of hypoxia.

- End-Tidal Nitrogen (EtN₂) & End-Tidal Carbon Dioxide (EtCO₂): Essential for detecting changes indicating VAE.

- Avoidance of Nitrous Oxide (N₂O): N₂O can expand air emboli and exacerbate VAE.

As Appropriate

- Esophageal Stethoscope: For detecting millwheel murmur in certain cases.

- Precordial Doppler: Non-invasive and sensitive for detecting air emboli.

- Transcranial Doppler: Useful in detecting cerebral air emboli.

Consider in Special Circumstances

- Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE): Highly sensitive and specific, recommended in high-risk procedures or when VAE is suspected.

Patient Positioning Improvements

- Advances in technical capabilities and surgical techniques have reduced the need for the sitting position in neurosurgical and orthopaedic surgeries.

- Alternative Positions:

- Prone or “Beach Chair” Position: Now commonly used, providing adequate surgical exposure while reducing VAE risk.

- Head-Up Positions: Used in many shoulder surgeries and procedures of the head and neck; however, these still carry a risk for VAE.

- Risk Mitigation:

- Leg Elevation: Flexion at the hip to decrease the negative gradient between open veins and the right atrium.

- Limiting Spontaneous Ventilation: Reduces negative pressure.

- Application of PEEP: Positive end-expiratory pressure can help maintain positive pressure in the venous system.

Central Venous Access

- Trendelenburg Position: Commonly used during insertion of central venous catheters in the internal jugular and subclavian veins to limit VAE risk.

- Increased Risk:

- Insertion of tunneled catheters through a peel-away sheath, used for haemodialysis lines and portocaths, carries a higher risk.

- Technique:

- Ensure meticulous technique during insertion and removal of central venous catheters.

- Prevent air entry during removal or through unprepared lines open to atmospheric pressure.

Minimizing Negative Pressure

- Intermittent Positive Pressure Ventilation: Helps prevent negative pressure.

- Application of PEEP: Maintains positive pressure in the venous system.

- Inspiratory Pause Hold: During central venous catheter placement and removal to minimize VAE risk.

Ensuring High Venous Pressure

- Euvolemia: Maintain adequate fluid balance to support venous pressure.

- Patient Positioning: Optimize positioning to maintain venous pressure and reduce VAE risk.

Avoidance of N₂O

- Nitrous Oxide (N₂O): Should be avoided as it can expand air emboli, worsening VAE.

Recommendations

- Low to Moderate Risk Procedures:

- Vigilant monitoring with standard anaesthetic monitors (EtCO₂, hemodynamic status).

- Surgical awareness and EtN₂ if available.

- Communication: Ensure the surgical team is aware of the risk and remains vigilant.

- High Risk Procedures:

- Surgeries with the site higher than the heart, laparoscopic cases with anticipated bleeding, or surgeries with high vascular exposure.

- Strongly consider using precordial Doppler in addition to usual monitoring.

- This method is cost-effective, easy to use, and minimally invasive.

Management of Venous Air Embolism (VAE)

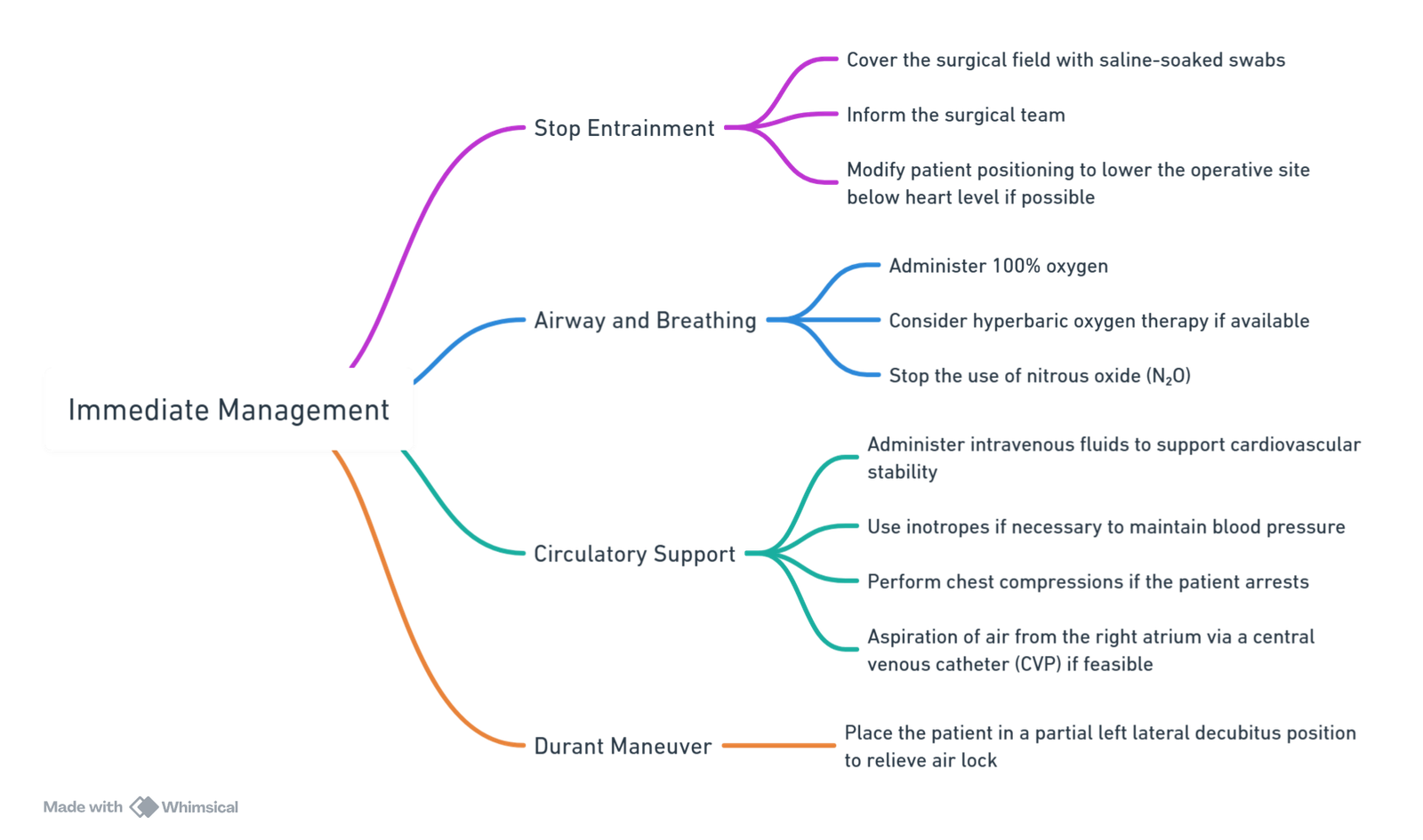

Immediate Management

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Detailed Management Steps

Stopping or Reducing Entrainment

- Increase Venous Pressure at the Operative Site

- Position the operative site below the level of the right atrium when possible.

- Decrease the driving pressure of the gas, especially when not atmospheric.

- Change Patient Position

- In cases of gas entrainment due to patient positioning, inform the surgeon and cover the surgical site with saline-soaked swabs.

- Change the patient’s position to reduce the gradient between the entry site and the heart.

- For cranial surgery, transient jugular venous compression may increase cerebral venous pressure and reduce air entrainment. However, this technique is not recommended for prolonged periods due to the risks of increased intracranial pressure, decreased cerebral perfusion, and potential stimulation of carotid sinuses leading to bradycardia.

- For surgeries below the thoracic level (e.g., laparoscopy, caesarean section, lumbar spine surgery), placing the patient in a reverse Trendelenburg position can help reduce further air entrainment.

- Stop Gas Insufflation

- Cease insufflation and decompress the abdomen during laparoscopic procedures to stop the source of embolism rapidly.

Preventing Further Entrainment

- Decrease Gaseous Pressure Gradient

- Positioning the operative site below the level of the right atrium when possible.

- Decrease the driving pressure of the gas.

- Intravenous Volume Loading

- Administer IV fluids to maintain euvolemia and support venous pressure.

- Increase Intrathoracic Pressure

- Perform a Valsalva maneuver to decrease venous return and reduce air entrainment.

- Maximize Oxygen Delivery

- Administer 100% oxygen to maximize oxygen delivery, eliminate nitrogen, and decrease embolic volume.

- Ensure adequate hemoglobin saturation and cardiac output.

Reducing Embolic Obstruction

- Durant Maneuver

- Place the patient in a partial left lateral decubitus position to relieve air lock in the right side of the heart (right ventricle).

- Alternatively, place the patient in the Trendelenburg position, which is often more feasible in surgical settings and beneficial for compromised hemodynamics.

- Aspirate Air from the Right Atrium

- Use a central venous catheter to aspirate air, though clinical success rates are low (6-16%).

- Multi-lumen central venous catheters and pulmonary artery catheters have limited effectiveness in aspirating air during VAE.

Cardiopulmonary Support

- Provide comprehensive cardiopulmonary resuscitation and support.

- Maintain hemodynamic stability with fluid resuscitation, inotropes, and other supportive measures as required.

Fat Embolism

Definition

- Fat embolism syndrome (FES): A rare clinical syndrome characterized by the presence of fat globules in the pulmonary circulation, commonly associated with long bone (especially femur) and pelvic fractures.

- Insult: Release of fat into the circulation causing pulmonary and systemic symptoms.

- Classic triad: Hypoxemia, neurological abnormalities, and petechial rash.

- Neurological abnormalities: Confusion, altered level of consciousness, seizures, focal deficit.

Clinical Manifestations

- Onset: Typically manifests 24 to 72 hours after the initial insult.

- Classic triad: Hypoxemia, neurologic abnormalities, petechial rash.

- Less common: Anemia, thrombocytopenia, fever, lipiduria, coagulation abnormalities, myocardial depression, shock.

- Non-specific features: None are specific for FES.

Incidence

- Highest incidence: Following trauma, particularly lower limb fractures.

- Other conditions: Soft tissue injury, liposuction, hepatic failure (fatty liver or necrosis), bone marrow harvest and transplant, burns, acute pancreatitis.

Diagnosis

- Clinical suspicion: Based on clinical findings.

- Imaging: CT or MRI.

- Laboratory tests: Blood tests, urine, free fatty acids (FFA), coagulation tests, CRP.

Schonfeld’s Criteria for Diagnosis of Fat Embolism Syndrome

- Petechiae: 5 points

- Chest X-ray changes (diffuse alveolar infiltrates): 4 points

- Hypoxemia (Pao₂ < 9.3 kPa): 3 points

- Fever (>38°C): 1 point

- Tachycardia (>120 beats/min): 1 point

- Tachypnea (>30 bpm): 1 point

Cumulative score >5 required for diagnosis.

Criteria for Diagnosis of Fat Embolism Syndrome

- Major Criteria (one necessary for diagnosis):

- Petechial rash

- Respiratory insufficiency

- Cerebral involvement

- Minor Criteria (four necessary for diagnosis):

- Tachycardia >120 beats/min

- Fever

- Retinal changes (fat or petechiae)

- Jaundice

- Renal signs (anuria or oliguria)

- Thrombocytopenia

- Anemia

- High erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Fat macroglobulinemia

One major plus four minor criteria with fat macroglobulinemia required for diagnosis.

Pathogenesis

Theories

- Mechanical theory: Microembolism

- Biochemical theory: Free fatty acids, cytokines, CRP

Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

Pathogenesis

- Orthopedic Trauma

- Long bone fracture

- Pelvic fracture

- Intraosseous access

- Non-Orthopedic Trauma (less common)

- Soft tissue injuries

- Chest compressions

- Bone marrow transplant

- Non-Trauma Related (rare)

- Pancreatitis

- Panniculitis (inflammation of subcutaneous fat)

- Diabetes mellitus

Mechanism

- Fat from bone marrow/adipose tissue: Leaks into bloodstream via damaged blood vessels.

- Obstructs dermal capillaries:

- Capillaries rupture

- Blood leaks into skin

- Petechial rash

- Fat globules in circulation:

- Damage blood vessel walls

- Platelet aggregation

- Blood clots form (disseminated intravascular coagulopathy)

- Cerebral vasculature obstruction:

- ↓ Blood flow and oxygen to brain

- Neurological findings: ↓ Level of consciousness, seizures

- Pulmonary vasculature obstruction:

- ↓ Pulmonary arterial blood flow → ↓ Gas exchange

- ↑ CO₂ and ↓ O₂ levels

- Respiratory center stimulation → Dyspnea/Tachypnea

- Right ventricular dysfunction:

- ↓ Blood pumping into systemic circulation

- Hypotension, Obstructive shock

- Obstructs dermal capillaries:

Prevention

- Early immobilization of fractures.

- Early operative intervention over conservative management.

- Limitation of intraosseous pressure during surgery.

- Steroids in high-risk patients.

Management

- Supportive treatment:

- Respiratory support: Intubation/ventilation, ARDS treatment (lung protective strategy).

- Hemodynamic support: Fluid resuscitation, vasopressors, invasive monitoring, TEE.

- Steroids: Consider in refractory cases (no strong evidence).

- Reduction of incidence/severity:

- Early immobilization of fractures.

- Operative correction rather than traction alone.

- Limitation of intraosseous pressure during orthopedic procedures.

Links

- Cement

- Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS)

- Amniotic fluid embolism and PE

- Anaesthesia emergencies

- Venous air embolism

- Polytrauma and haemorrhagic shock

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

- Positioning

References:

- Mao, Y., Wen, S., Chen, G., Zhang, W., Ai, Y., & Yuan, J. (2017). Management of intra-operative acute pulmonary embolism during general anesthesia: a case report. BMC Anesthesiology, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-017-0360-0

- Yang, A., Zhang, S., Xing, Y., & Zhang, R. (2019). Management of intraoperative acute pulmonary embolism in a patient with subarachnoid haemorrhage undergoing femoral fracture repair. Journal of International Medical Research, 47(10), 5307-5311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060519874158

- Cruz, G., Pedroza, S., Giraldo, M., Peña, A. D., Calderón, C. A., & Quintero, I. F. (2023). Intraoperative circulatory arrest secondary to high-risk pulmonary embolism. case series and updated literature review. BMC Anesthesiology, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-023-02370-z

- Luff, D. and Hewson, D. W. (2021). Fat embolism syndrome. BJA Education, 21(9), 322-328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2021.04.003

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- ICU One Pager. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://onepagericu.com/

- Intra-operative Embolic Phenomena. Dr Lance Lasersohn. Wits refresher. 2013

Summaries:

Fat embolism

Gas embolism

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “96e11221-2685-40e4-ac1f-a1004b0946a9”