{}

Summary

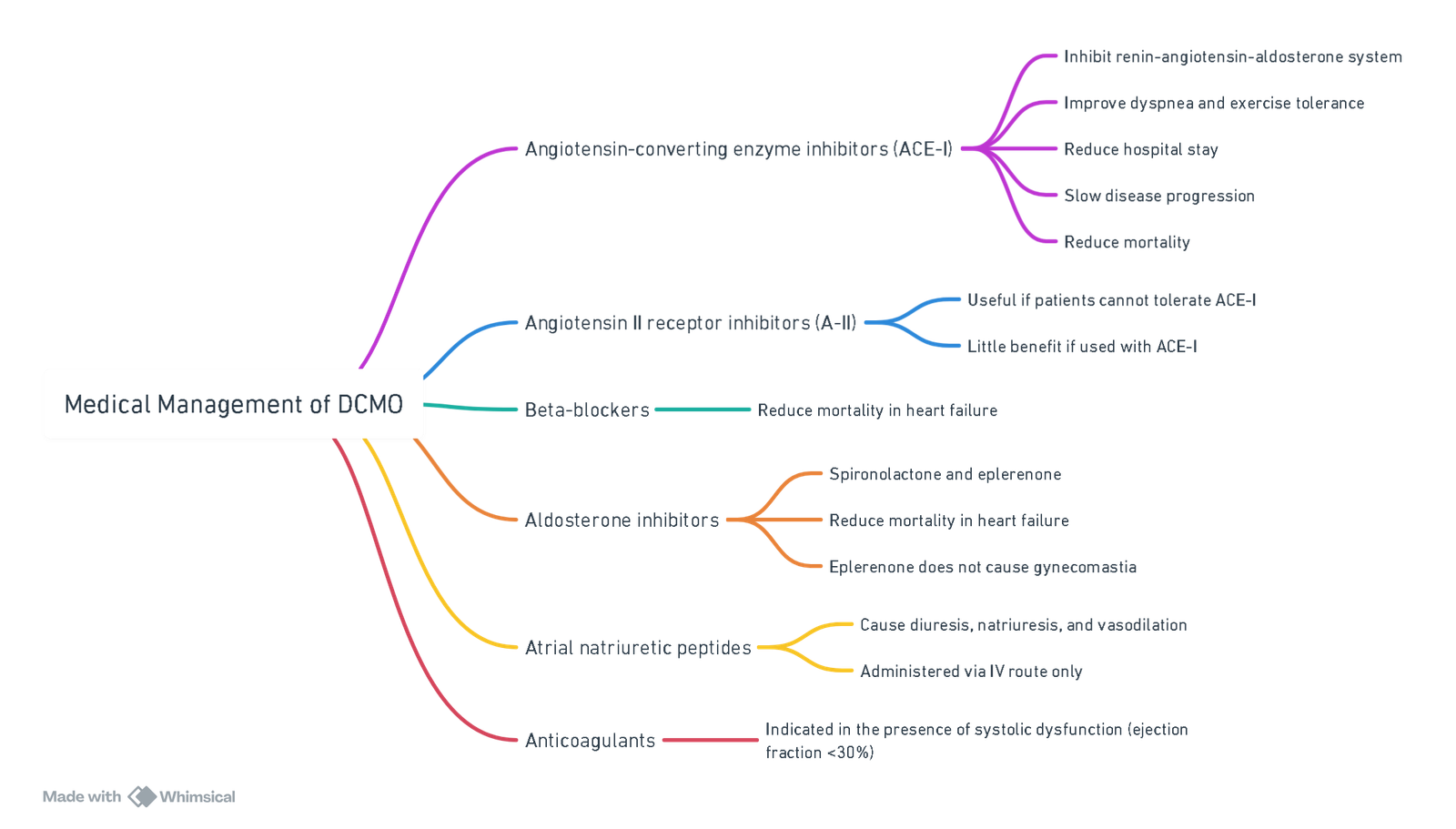

- Pathogenesis, classification, features, diagnosis, pre op Mx, intra op goals and monitoring of patients with cardiomyopathy

Classification

European Society of Cardiology Working Group on myocardial and pericardial diseases from 2007. It defines myocardial disorders and provides a classification. Here’s a summary of the content:

Definition: A myocardial disorder is a condition in which the heart muscle is structurally and functionally abnormal, in the absence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, valvular disease, and congenital heart disease sufficient to cause the observed myocardial abnormality.

Classification:

- DCM (Dilated Cardiomyopathy)

- HCM (Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy)

- RCM (Restrictive Cardiomyopathy)

- ARVR (Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy)

- Unclassified group

These groups are further divided into familial (genetic) and non-familial (non-genetic) subgroups.

DCMO

Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

Etiology

- Viral myocarditis (including HIV)

- Autoimmune

- Muscular dystrophy

- Myocardial ischemia

- 75% of non-idiopathic DCM

- Inherited disorders

- Hemochromatosis

- Chronic alcoholism

Pathophysiology

- Initial Damage

- Inflammatory damage to myocytes and myocyte death.

- Myocyte toxicity and damage from chronic alcoholism.

- Myocardial Remodelling

- Eccentric fibrosis of myocardium (sarcomeres added in series, increased chamber volume).

- Enlargement of the LV chamber without a corresponding increase in myocardial mass.

- Decreased contractile ability, initially partially compensated.

- Compensation leads to further LV dilation, damage, and negative remodelling.

- Progression to Systolic Dysfunction

- Inability to compensate due to further damage.

- Systolic dysfunction leads to hemostasis in ventricles and increased risk of thrombus.

- Lack of forward flow and volume overload resulting in decreased CO and increased EDV/EDP.

- Volume overload/CHF.

Clinical Findings

- Compensation Mechanisms

- CO preserved by increased SV due to increased muscle unit stretch (Frank-Starling law).

- CO also preserved by increased HR.

- Decreased BP leading to decreased end-organ perfusion.

- Upregulation of RAAS.

- Aldosterone: Na+ and H2O retention.

- Angiotensin II: Peripheral vasoconstriction.

Symptoms and Signs

- Tachycardia

- Pre-renal failure

- Increased BUN & creatinine

- Cool, clammy extremities

- Diffuse pulmonary crackles/CXR evidence

- Dyspnea

- Tachypnea

- Peripheral edema

- Hepatic congestion

- Sudden cardiac death

Echo Features

- Fractional shortening less than 25% and/or ejection fraction less than 45%

- TAPSE < 14 mm illustrates right ventricular dysfunction and predicts a poor prognosis.

- Diastolic dysfunction (restrictive or pseudonormal) is associated with a poor prognosis

- Mitral regurgitation is frequently seen in patients with DCM

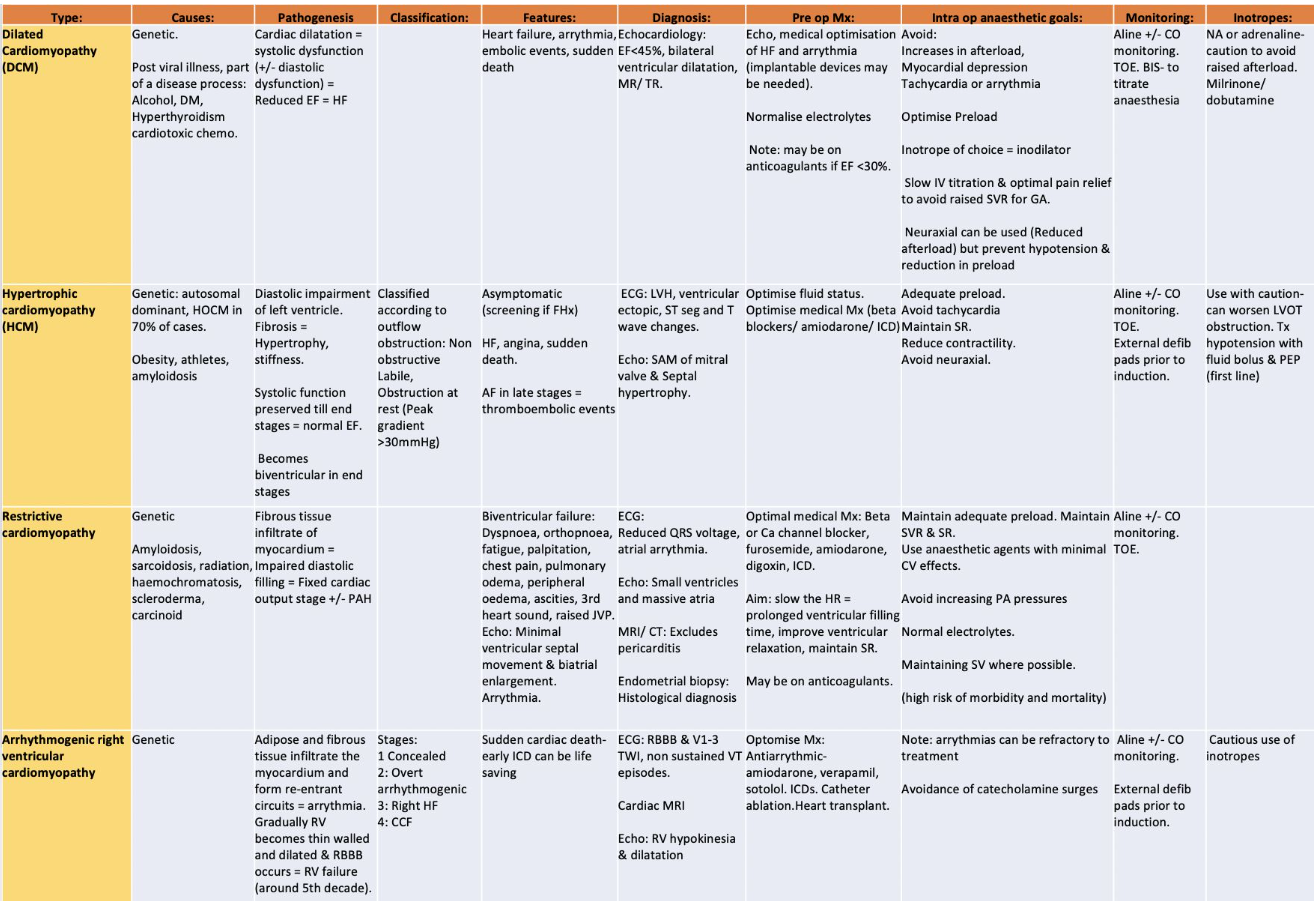

Medical Management

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Non-Medical Management of Advanced Heart Failure

- Partial left ventriculectomy.

- Left ventricle assist devices.

- Multi-site ventricular pacing.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs).

- Heart transplantation.

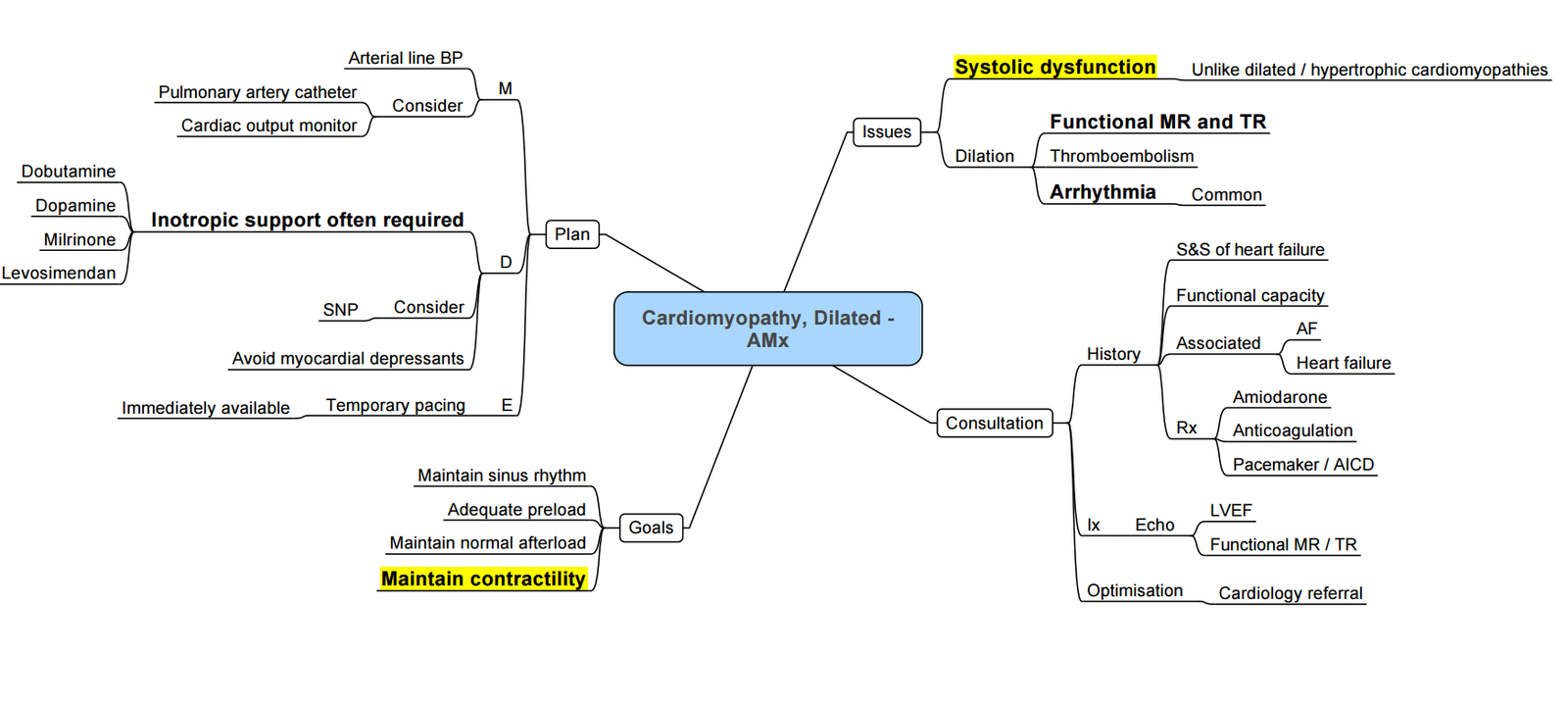

Anaesthesia for DCMO

Preoperative Management

-

Medical Therapy:

- Continue regular medications for all patients.

- Optimize medications for patients with symptoms of heart failure.

-

Arrhythmia Management:

- Treat arrhythmias before surgery using drug therapy and/or device implantation to achieve rate and rhythm control.

-

Echocardiography:

- Perform echocardiography to assess the extent of ventricular dysfunction and identify any valvular abnormalities.

Intraoperative Management

-

Goals:

- Avoid myocardial depression.

- Maintain adequate preload and prevent increases in afterload.

- Avoid tachycardia.

- Prevent sudden hypotension by carefully titrating anaesthetic agents.

-

Local and Regional Anaesthesia Techniques:

- Peripheral Nerve Blocks:

- Offer minimal haemodynamic changes.

- Central Neuraxial Blockade:

- Reduces afterload and improves cardiac output.

- Prevent accompanying hypotension to avoid myocardial hypoperfusion.

- Peripheral Nerve Blocks:

-

General Anaesthesia:

- Avoid overdose of induction agents due to impaired circulation time.

- Etomidate:

- Causes minimal haemodynamic changes.

- Ketamine:

- Should be avoided as it increases systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

- Propofol:

- Has a negative inotropic effect but useful in reducing SVR.

- Volatile Anaesthetic Agents:

- Cause myocardial depression at high concentrations.

- Opioids:

- Have minimal cardiovascular effects and reduce the requirement for anaesthetic agents.

-

Monitoring:

- Use arterial and central venous catheters.

- Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) for dynamic myocardial function assessment.

- Consider oesophageal Doppler if TOE is unavailable.

- Use bispectral index monitoring to titrate anaesthetic agents.

-

Cardiovascular Support:

- Provide inotropic support with agents such as phosphodiesterase inhibitors, levosimendan, dobutamine, and dopamine.

- Use noradrenaline for treating hypotension, ensuring careful management to prevent sudden increases in afterload.

- Consider biventricular pacing and intra-aortic balloon pump for patients with severe systolic dysfunction.

Postoperative Management

- Transfer patients to an intensive care unit for invasive monitoring and optimization of postoperative haemodynamics and fluid therapy.

- Provide adequate analgesia to reduce the deleterious effects of increased SVR.

Predictors of Poor Outcome

- Left ventricular ejection fraction <20%.

- Elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP).

- Left ventricular hypokinesia.

- Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM): Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

Definition

- Primary cardiac muscle hypertrophy of the left ventricle in the absence of other structural or functional abnormality

Notes

- Cardiomyopathy: Pathological process involving changes in myocyte structure, leading to decreased myocardial function.

- Myocyte disarray: Gives HCM its arrhythmogenic potential, not present in left ventricular hypertrophy seen in chronic hypertension.

Etiology

- Familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- More than 50% of HCM

- Autosomal mutation in genes encoding myosin, troponin, or myosin-binding proteins

- Most common form of inherited cardiac malformation, affecting 1 in 500 adults

- Unknown or undefined cause

Pathophysiology

- Can be asymmetrical, concentric, midventricular, and apical. It can also involve the right ventricle.

- Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) occurs in 70% of these cases

- Diastolic impairment of the left ventricle is the major pathophysiological abnormality in HCM

- Extracellular fibrosis results in increasing hypertrophy, ventricular stiffness, shape distortion, and further diastolic impairment.

- The systolic function remains normal with high ejection fraction until the later stages of the disease when patients develop biventricular systolic dysfunction due to myocardial fibrosis

-

Myocardial Changes

- Thickening and disarray of left ventricular myocardium.

- Impaired ventricular filling during diastole (diastolic dysfunction).

- Disorganized myocytes disrupt signal conduction, leading to ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.

-

Obstructive Component (HOCM)

- Thickening of septum (25% of HCM cases).

- Narrowed left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) causes blood flow in the tract to accelerate.

- Faster movement of blood leads to lower pressure in LVOT (Venturi effect).

- Low pressure area draws anterior leaflet of the mitral valve into outflow tract during systole, blocking outflow of blood into aorta.

- As contractility decreases, obstruction lessens; blood is again ejected into aorta at end-systole.

-

Hemodynamic Consequences

- Decreased Stroke Volume (SV)

- Leads to reduced cardiac output (CO = SV x HR).

- Decreased SV causes left-sided pressure and blood backs up into the lungs, resulting in pulmonary edema.

- Double-tap or “bifid” pulse

- Systolic murmur (accentuated by Valsalva maneuver)

- Audible S4 heart sound due to atrial contraction in late diastole (if in sinus rhythm).

- Decreased Stroke Volume (SV)

Clinical Findings

- Pulmonary Symptoms

- Diffuse crackles on auscultation

- Dyspnea

- Tachypnea

- Cardiovascular Symptoms

- Fatigue

- Anginal chest pain

- Other Signs

- Tissue hypoxia

- Decreased coronary artery perfusion

- Increased airflow resistance

- Increased work of breathing

- Stimulus to breathe due to hypoxia (Increased RR)

- Decreased myocardial oxygen supply coupled with increased demand from hypertrophic myocytes

Classification of Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction (LVOTO)

-

Non-Obstructive:

- No obstruction under provocation or resting conditions.

- Peak gradient <30 mm Hg.

-

Labile:

- Obstruction occurs only during provocation.

- Peak gradient >30 mm Hg only during provocation.

- Diagnostic manoeuvres to provoke LVOTO include:

- Valsalva manoeuvre.

- Administration of a potent inhaled vasodilator, such as amyl nitrite.

- Exercise treadmill testing.

-

Obstructive at Rest:

- Obstruction is present at rest.

- Peak gradient >30 mm Hg.

- Approximately one-third of patients will have obstruction at rest.

- Another one-third will have labile obstruction.

- The remaining one-third will have no obstruction under any conditions.

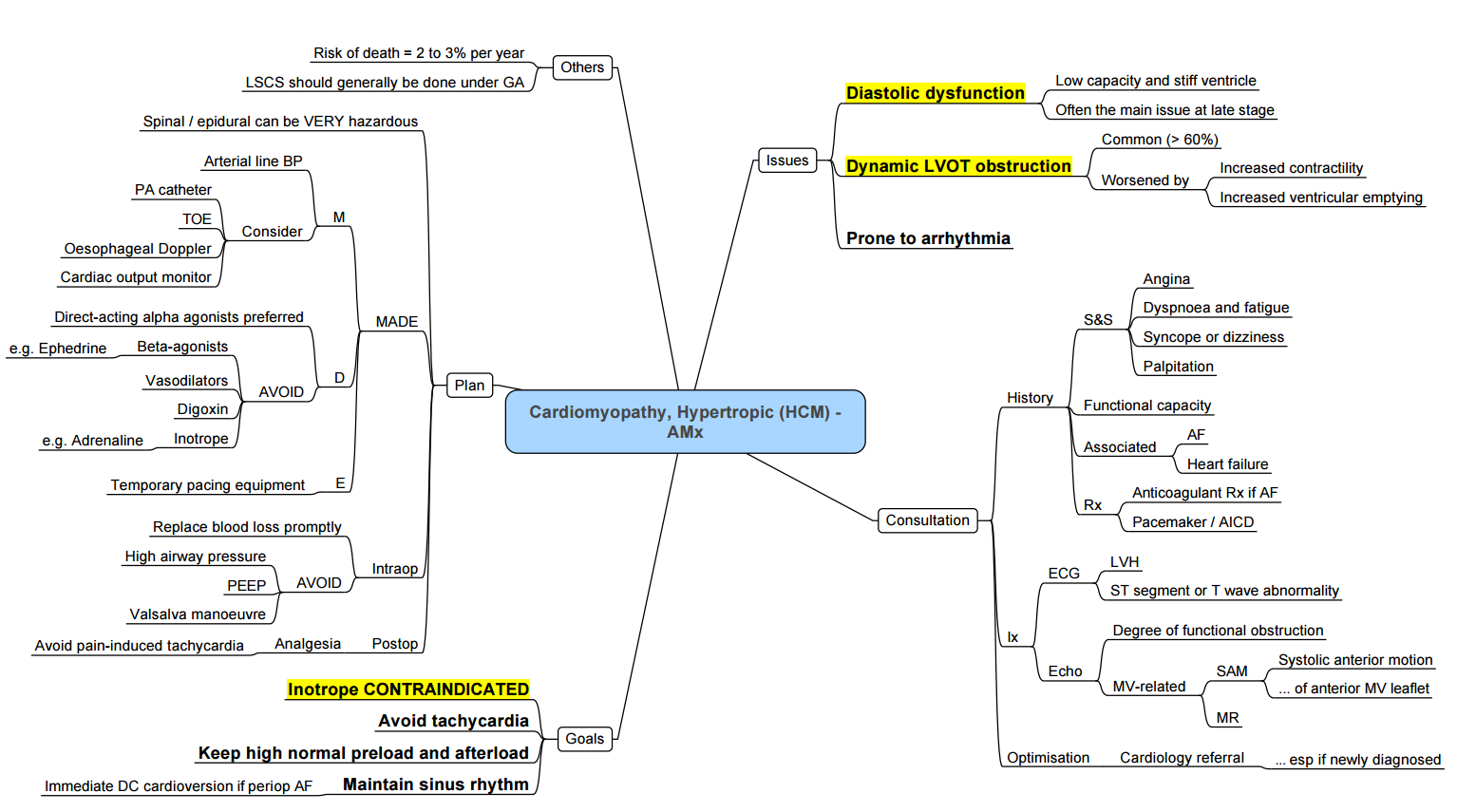

Anesthesia for HCM

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

- Definition

- impairment of ventricular diastolic function due to fibrotic or infiltrative changes in the myocardium and or subendocardium.

- Reduce diastolic ventricular compliance and elevate ventricular end-diastolic pressure.

- Patients with RCM can have normal or near-normal systolic function in the early stages of the disease.

Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

Etiology

- Amyloidosis

- Abnormal deposition of amyloid protein in organs.

- Sarcoidosis

- Abnormal granulomas in organs, often leading to dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Hemochromatosis

- Genetic mutation leading to increased iron absorption and body iron levels.

- Endomyocardial fibrosis

- Idiopathic fibrotic process, common in tropical/subtropical regions.

Pathophysiology

-

Myocardial Infiltration

- Infiltration of myocardium by pathological proteins (e.g., amyloidosis, sarcoidosis).

- Infiltration and dysfunction of conduction system, leading to arrhythmias.

- Endomyocardial fibrosis resulting in stiffening of the ventricular walls.

- Iron deposition as haemosiderin in organs, including the heart.

-

Ventricular Compliance and Filling

- Stiffening of the left (and often right) ventricular walls leads to diastolic dysfunction.

- Increased ventricular pressure during diastolic filling phase.

- Pressure propagates to the right heart.

- Increased venous pressure leads to right-sided failure.

Hemodynamic Consequences

- Impaired Ventricular Filling

- Decreased stroke volume.

- Decreased cardiac output.

- Tissue hypoxia due to impaired muscle perfusion.

- Easy filling initially, but very hard filling later due to high filling pressure.

- Ventricular wall compliance decreases.

Clinical Findings

- Arrhythmia

- Elevated JVP

- Prominent y-descent, atrial emptying then peak and plateau.

- Hepatic Congestion

- Ascites.

- Hepatomegaly.

- Peripheral Edema

- Fatigue

- Dyspnea

- Tachypnea

Auscultation Findings

- S4 heart sound

- Due to atrial contraction pushing blood into stiff ventricle.

- “Dip-and-plateau” pressure tracing in the ventricle

Echocardiography Findings

- Pronounced bi-atrial enlargement.

- Relatively little ventricular septal movement during respiration.

- Very occasional ventricular septal movement during diastole.

Medical Management

- Beta-Blockers

- Diuretics

- Antiarrhythmic Medications:

- Amiodarone

- Digoxin

- Permanent Pacemakers and ICDs:

- Indicated for patients with advanced conducting system dysfunction.

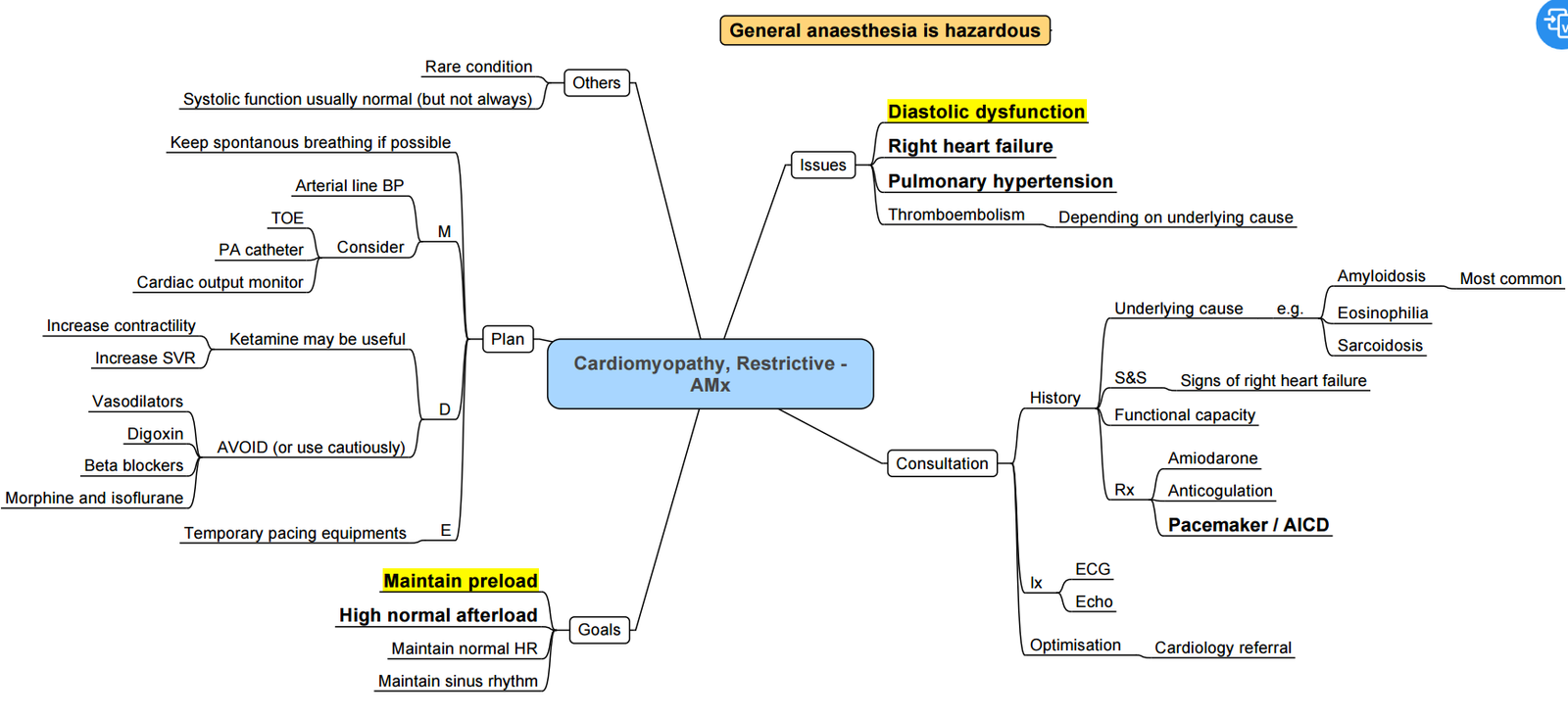

Anaesthesia Considerations

-

High Risk:

- Increased risk of morbidity and mortality.

-

Monitoring:

- Use arterial line (A-line).

- Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE).

-

Anaesthetic Goals:

- Maintain adequate preload.

- Maintain systemic vascular resistance (SVR).

- Maintain sinus rhythm.

- Use anaesthetic agents with minimal cardiovascular effects:

- Ketamine

- Etomidate

Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy

Definition:

- Cardiomyopathy associated with liver cirrhosis is characterized by:

- Impaired contractile responsiveness to physiological or pharmacological stress.

- Impaired left ventricular relaxation.

- Electrophysiologic abnormalities, including a prolonged QT interval.

Clinical Characteristics:

- Systolic and Diastolic Dysfunction:

- Patients exhibit both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.

- There is a blunted response to β-adrenergic receptor agonists, indicating that vasopressor therapy may not be effective at traditional doses.

Electrophysiologic Changes:

- Prolonged QT interval is a notable feature of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy.

Prevalence:

- These cardiac abnormalities may exist to some degree in all patients with liver cirrhosis, reflecting the underlying pathophysiological changes associated with cirrhosis.

Key Points for Clinical Management

- Impaired Contractile Response:

- Patients may not respond adequately to typical doses of β-adrenergic agonists.

- Monitoring and Treatment Adjustments:

- Given the impaired response to vasopressors, careful monitoring and possibly higher or alternative dosing strategies may be required.

- Electrophysiological Monitoring:

- Regular monitoring for prolonged QT intervals and other electrophysiologic changes is essential.

See Cardiac disease in pregnancy for PPCM

Links

- Cardiac physiology

- Cardiac for non-cardiac surgery

- Heart failure

- Valvular heart disease

- Anaesthetic management of specific cardiac conditions

- Cardiac disease in pregnancy

References:

- Ibrahim, I. R. and Sharma, V. R. (2017). Cardiomyopathy and anaesthesia. BJA Education, 17(11), 363-369. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkx022

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

HOCM

Cardiomyopathy

Cardiomyopathy_Mindmap

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “8ec7b54e-a011-480d-abff-e0916064231b”