- Summary of Heart Failure and Anaesthesia

- Heart Failure

- Physiology

- Frank-Starling and Cardiac Failure and Laplace

- Diastolic Heart Failure

- Systolic Heart Failure

- Compensation Mechanisms

- Treatment Recommendations

{}

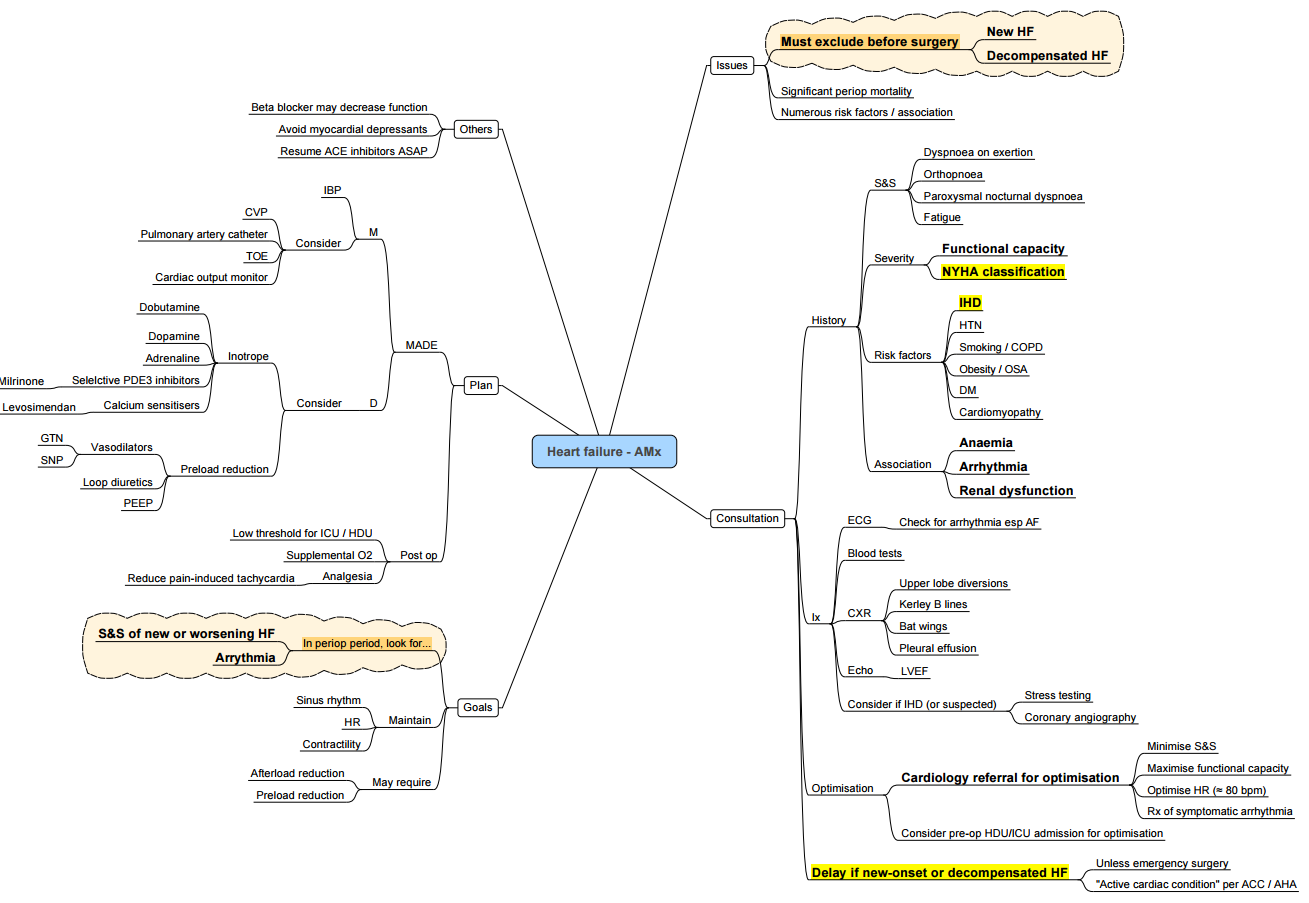

Summary of Heart Failure and Anaesthesia

- Major risk factors

- age, hypertension and coronary artery disease

Heart Failure

ACC/AHA Stages of Heart Failure

- A: At high risk for HF but without structural heart disease or symptoms of HF.

- B: Structural heart disease but without signs or symptoms of HF (NYHA Class I).

- C: Structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of HF (NYHA Class I-IV).

- D: Refractory HF requiring specialized interventions (NYHA Class IV).

Diagnosis of Heart Failure (HF)

| Criteria | HFrEF (Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction) | HFmrEF (Heart Failure with Mid-Range Ejection Fraction) | HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Symptoms ± signsa | Symptoms ± signsa | Symptoms ± signsa |

| 2 | LVEF < 40% | LVEF 40-49% | LVEF > 50% |

| 3 | – | 1. Elevated levels of natriuretic peptides; 2. At least one additional criterion: A relevant structural heart disease (LVH and/or LAE), Diastolic dysfunction | 1. Elevated levels of natriuretic peptides; 2. At least one additional criterion: A relevant structural heart disease (LVH and/or LAE), Diastolic dysfunction |

Modified Framingham Criteria for Congestive Heart Failure

| Major Criteria | Minor Criteria |

|---|---|

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea or orthopnoea | Bilateral ankle oedema |

| Central venous pressure > 16 cmH2O | Nocturnal cough |

| Pulmonary rales | Dyspnoea on exertion |

| Cardiomegaly | Hepatomegaly |

| Acute pulmonary oedema | Pleural effusion |

| Third heart sound gallop | Tachycardia (heart rate ≥ 120 beats/min) |

| Weight loss > 4.5 kg in 5 days in response to treatment | Weight loss > 4.5 kg in 5 days in response to treatment |

Diagnosis: The diagnosis of heart failure requires that either two major or one major and two minor criteria are met.

Paediatric Classification of Heart Failure

| Class | Description |

|---|---|

| Class I | Asymptomatic |

| Class II | Mild tachypnea or diaphoresis with feeding in infants; Dyspnea on exertion in older children |

| Class III | Marked tachypnea or diaphoresis with feeding in infants. Prolonged feeding times with growth failure; Marked dyspnea on exertion in older children |

| Class IV | Symptoms such as tachypnea, retractions, grunting, or diaphoresis at rest |

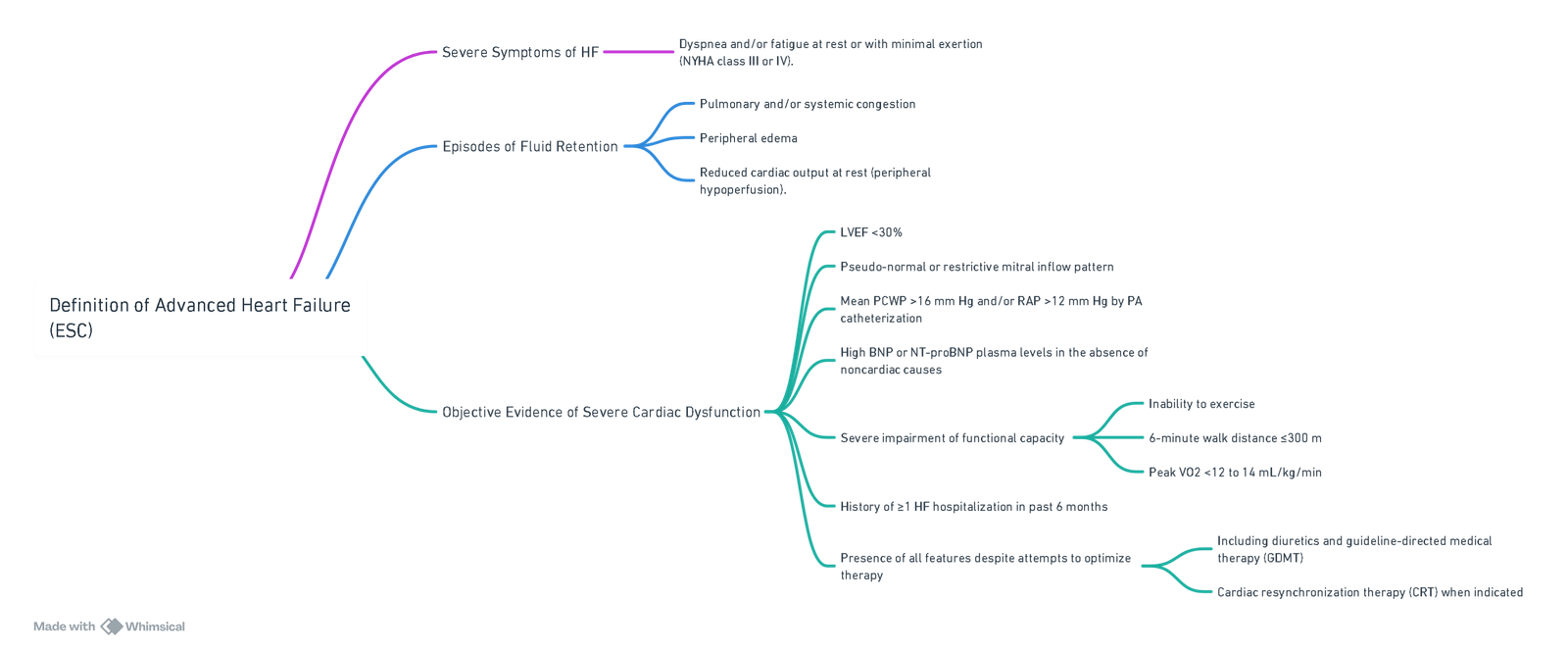

European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Definition of Advanced HF

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Physiology

- High-output heart failure: CO is normal but the tissue O2 demand is high; for example, thyrotoxicosis and pregnancy.

- Low-output heart failure: The tissue’s O2 demand is normal, but the CO is insufficient to meet it.

Consequences

- Forward HF: Decreased O2 delivery to tissues resulting in renal failure, fatigue, and ischemic heart disease.

- Backward HF: Increased left atrial pressure (LAP), pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), increased hydrostatic pressure, and fluid extravasation with pulmonary edema. Increased right ventricular (RV) afterload and right heart failure, leading to edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly.

Frank-Starling and Cardiac Failure and Laplace

- When cardiac sarcomeres are stretched beyond their optimal length, the tension generated during contraction is reduced.

- Greater ventricular radius: For the same active tension generated in the ventricular wall, a left ventricle (LV) of greater radius will produce a lower pressure than a ventricle of smaller radius, increasing myocardial work required to generate the same pressure.

Diastolic Heart Failure

Pathogenesis

Conditions Causing Chronic Pressure Overload or Volume Overload in the Left Ventricle (LV)

- Pressure Overload: Chronic conditions such as aortic stenosis, hypertension, and cardiomyopathy.

- Volume Overload: Conditions such as aortic and mitral regurgitation, and left heart failure.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms

Increased Myocardial Wall Stress

- Chronic pressure or volume overload leads to increased myocardial wall stress, which induces left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH).

LV Compensation Mechanisms

Pressure Overload (Concentric Hypertrophy)

- Mechanism:

- LV compensates to maintain stroke volume against afterload by thickening the myocardial wall.

- This involves:

- Activation of fibroblasts, increased contractile protein synthesis, sarcomere addition in parallel, increase in the number of myocytes, excess myocyte hypertrophy, and increased fibrosis of ECM.

- Result:

- Chronic increase in the ratio of wall thickness to chamber dimension, leading to concentric hypertrophy.

Volume Overload (Eccentric Hypertrophy)

- Mechanism:

- LV compensates to preload by lengthening the myocardial wall to maintain stroke volume (Frank-Starling Law).

- This involves:

- Activation of ECM proteinases, proteolytic degradation, sarcomere addition in series, increase in the length of existing myocytes, increased elasticity, and muscle fiber movement.

- Result:

- LV dilation and increased chamber size.

- Chronic increase in the ratio of wall thickness to chamber dimension, leading to eccentric hypertrophy.

Neurohormonal Activation

- Stretching force on myocytes activates neurohormonal mechanisms involving the RAAS, epinephrine, and norepinephrine, further promoting hypertrophy.

Detection and Prognosis

- LVH is often asymptomatic and diagnosed through ECG or ECHO. Initially involves compensatory mechanisms; however, adverse outcomes occur with long-standing hypertrophy. Hypertrophy leads to increased stiffness, reduced compliance, and higher risk of heart failure.

Specific Conditions

- Conditions like amyloidosis, sarcomere mutations, and specific cardiomyopathies can result in atypical presentations of LVH. Reduced ventricular compliance decreases diastolic filling and stroke volume (SV), leading to backward failure and pulmonary edema.

Systolic Heart Failure

Pathophysiology

Frank-Starling Mechanism

- Represents the relationship between preload and stroke volume. As preload increases, stroke volume increases to a point, beyond which the heart fails to generate sufficient stroke volume during systole.

Myocardial Dysfunction

- Left ventricular dysfunction leads to decreased cardiac output (CO) and blood pressure (BP), resulting in activation of compensatory mechanisms to maintain perfusion.

Compensatory Mechanisms

Anti-Diuretic Hormone (ADH) Activation

- Stimuli: Decreased BP and carotid sinus baroreceptor activation.

- Result: Increased ADH release.

- Effect: Arginine vasopressin activation leading to renal collecting ducts’ water retention.

Adrenal Gland Activation

- Effect: Aldosterone release resulting in sodium retention in renal distal tubules.

RAAS System Activation

- Stimuli: Decreased BP and sympathetic activation of the juxtaglomerular kidney cells due to renal hypoperfusion.

- Effect: Angiotensin II and aldosterone receptor activation, leading to increased SVR and myocardial collagen synthesis and hypertrophy.

SNS Activation

- Stimuli: Decreased CO and BP.

- Effect: Catecholamine release (norepinephrine and epinephrine) leading to α1 and β receptor activation.

- Result:

- α1 receptor activation: Increased SVR.

- β1 receptor activation: Increased HR to maintain CO.

Maladaptive Responses

- Increased Preload (EDV): Volume overload due to the Frank-Starling mechanism leading to systemic and pulmonary venous congestion.

- Increased Afterload: Resistance to ejection leading to reduced stroke volume.

- Chronic β-Receptor Activation: Cardiomyocyte apoptosis and fibrosis, decreasing myocardial contractility.

- Increased HR: Tachycardia maintains CO initially but leads to increased myocardial oxygen demand and ischemia.

Important Equations

- BP = CO x SVR: BP: Blood Pressure, CO: Cardiac Output, SVR: Systemic Vascular Resistance.

- CO = SV x HR: SV: Stroke Volume, HR: Heart Rate.

- Stroke Volume Affected by: Preload (Frank-Starling mechanism), Afterload (arterial resistance), Contractility (LV myocytes).

Pathology

- Pump inadequacy causing forward heart failure resulting in inability to meet metabolic requirements. May be low output (too low CO, normal metabolic requirements) or high output (normal CO, too high metabolic requirements). Either due to myocyte damage or increased chronically afterload.

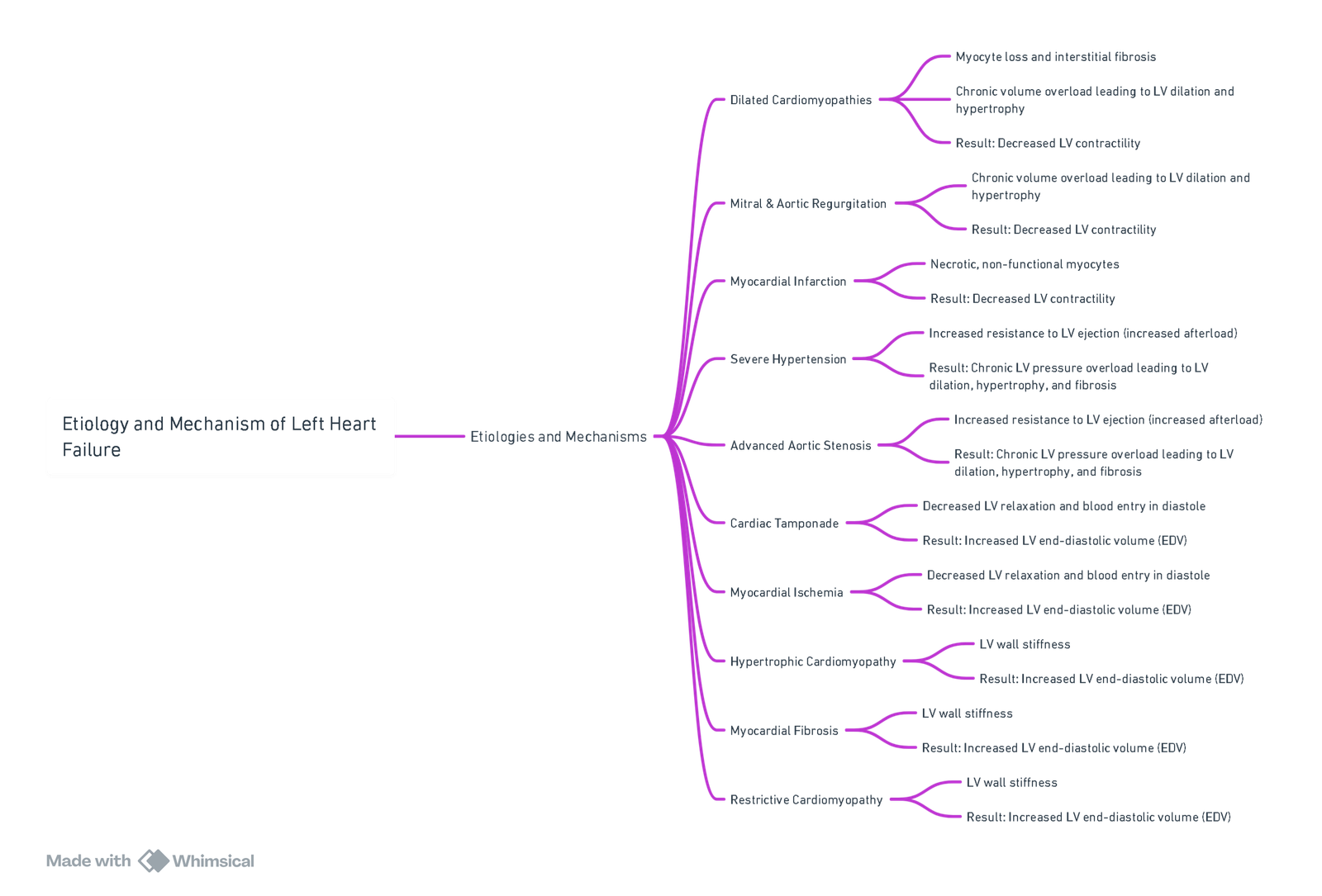

Left Heart Failure

Etiologies and Mechanisms

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Consequences

Systolic Dysfunction

- Definition: LV can’t squeeze/empty well, leading to reduced ejection fraction (EF).

- Note: EF = Stroke Volume (SV) / End-Diastolic Volume (EDV). Normal EF = 55-75%.

Diastolic Dysfunction

- Definition: LV can’t relax/fill well even though ejection fraction is preserved.

Normal Cardiac Physiology

- Stroke Volume (SV) Depends on:

- Preload: End-diastolic volume (EDV).

- Afterload: Resistance to LV ejection.

- Contractility: Inherent strength of myocardial contraction.

- Ejection Fraction (EF):

- EF = Stroke Volume (SV) / End-Diastolic Volume (EDV).

- Percentage of the LV’s EDV ejected in systole.

- Normal EF = 55-75%.

Clinical

Systolic Dysfunction

- Pathophysiology:

- If LV is dilated, atrial blood flow during systole is turbulent, leading to a diffuse apical beat and increased blood pressure in systole and pulse pressure.

- If LV is pressure overloaded or hypertrophic, a sustained apical beat is present.

Diastolic Dysfunction

- Pathophysiology:

- Atrial contraction against stiff LV in late diastole causes turbulent blood flow during diastole, leading to a diffuse apical beat and increased blood pressure in diastole and pulse pressure.

Cardiac Output

- Effects of Reduced Cardiac Output:

- Decreased perfusion of tissues (brain, kidneys) leads to decreased urine output and level of consciousness.

- Increased sympathetic activity to try to restore CO results in tachycardia and diaphoresis.

- Reflexive increase in sympathetic activity leads to increased sweat gland activity, heart activity, and respiratory activity (tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis).

Blood and Oxygenation

- Increased End-Diastolic Pressure (EDP):

- More blood remains in LV after systole, leading to increased LV end-diastolic pressure. Blood backs up into lungs, causing pulmonary vascular pressure increase.

Pulmonary Symptoms

- Pulmonary Venous Congestion:

- Forces fluid out of capillaries into transudative pulmonary edema, resulting in vascular congestion, edematous alveolar congestion, and decreased blood oxygenation.

- Loud P2:

- Pulmonic valve shuts with greater force than normal, causing a loud P2 sound on auscultation.

- Wheezing (Rhonchi):

- Transudate obstructs small airways/alveoli, and turbulent airflow is heard on auscultation.

- Pulmonary Crackles:

- Usually bilateral, starts at lung bases. Fluid accumulation in small airways/alveoli causes crackling sounds on auscultation.

Right Heart Failure (Secondary)

- Prolonged Increased Pulmonary Vascular Pressure:

- Prolonged overexertion of the right ventricle can lead to right heart failure.

- Systemic Venous Congestion:

- Presents as peripheral (e.g., ankle) edema, pleural effusions, hepatic congestion/ascites.

Physical Signs

- Diffuse Apical Beat: Indicates turbulent blood flow during systole or diastole.

- Sustained Apical Beat: Indicates LV pressure overload or hypertrophy.

- Cool Extremities, Peripheral Cyanosis: Due to peripheral vasoconstriction.

- Diaphoresis: Increased sweat gland activity.

- Tachycardia: Increased heart rate.

- Tachypnea: Increased respiratory rate.

- Loud P2, Wheezing, Pulmonary Crackles: Due to pulmonary congestion and edema.

Note: Left heart failure is the main cause of right heart failure. Features of left heart failure depend on the underlying cause.

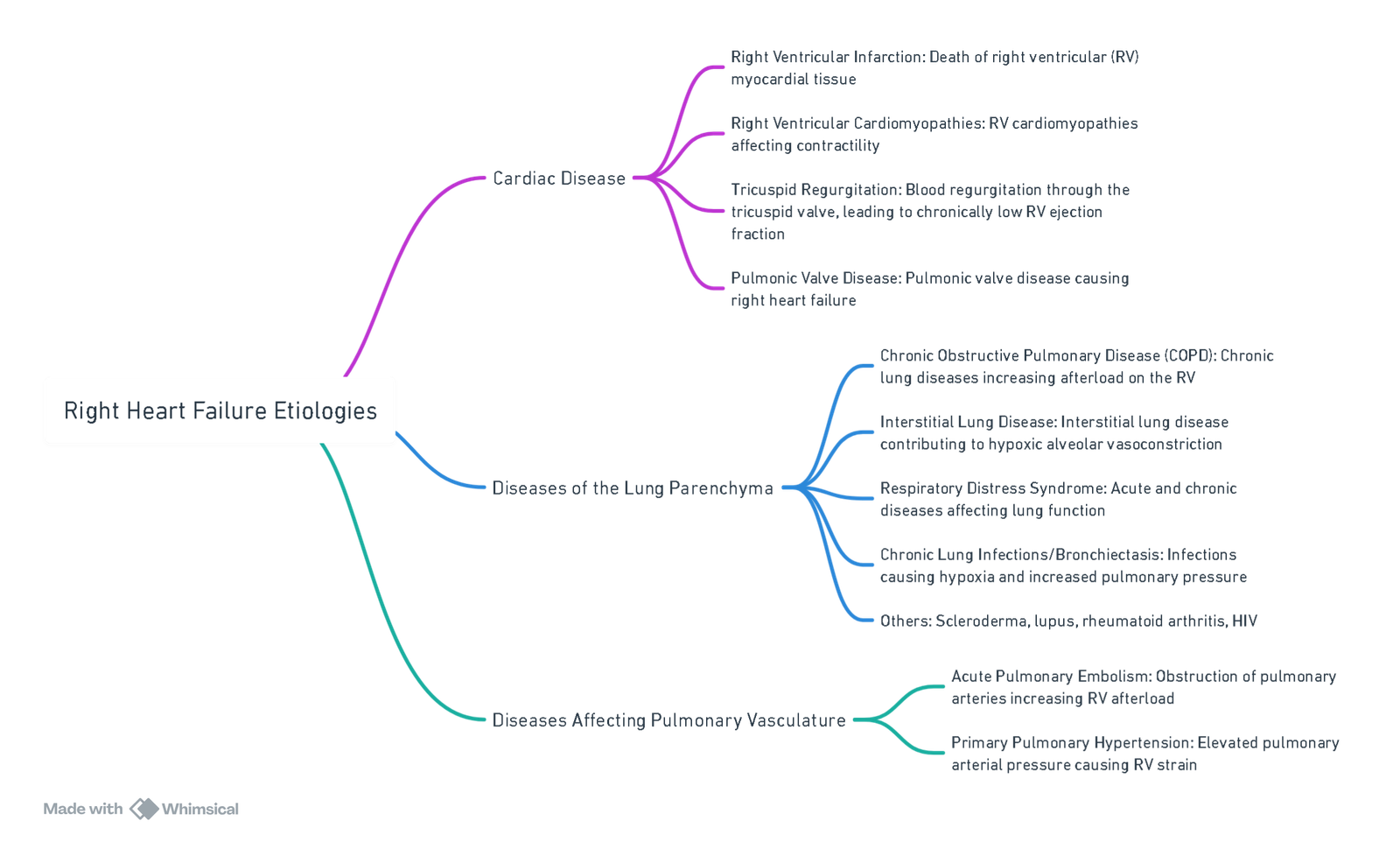

Right Heart Failure

Etiologies and Mechanism

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Pathophysiology

Increased Afterload on RV

- Mechanism:

- Left heart failure or lung parenchyma diseases cause increased pulmonary blood pressure, leading to increased RV afterload. Chronic hypoxia causes pulmonary vasoconstriction, increasing vascular resistance and RV strain.

- RV Tension:

- Stretches myocytes’ myofilaments to longer than their optimal contraction length, making it harder for RV to eject blood (Frank-Starling Law).

RV Failure

- Effects:

- Decreased right ventricular stroke volume. Blood backs up into systemic venous vasculature, increasing venous pressure and leading to systemic congestion.

Clinical Findings

Systemic Venous Congestion

- High Jugular Venous Pressure (JVP): Positive abdominal-jugular reflex due to inability of RV to pump blood efficiently.

- Peripheral Pitting Edema: Starts at the feet and progresses upwards as venous congestion worsens, potentially leading to ascites.

- Hepatomegaly: Liver congestion causing hepatomegaly and right upper quadrant discomfort.

- Ascites: Fluid accumulation in the abdomen due to increased venous pressure.

- Splenomegaly: Spleen congestion and enlargement.

Pulmonary Findings

- Loud P2: Increased pulmonary component of S2, may be palpable.

- Pulmonic Valve Murmur: Due to high resistance and turbulent blood flow.

- RV Heave: Palpable sign indicating RV hypertrophy or enlargement.

Notes:

- The most common cause of right-sided heart failure is left-sided heart failure.

- Isolated right heart failure not due to left heart failure is called “cor pulmonale.”

- Clinical findings depend on the specific underlying cause (e.g., dyspnea in COPD).

Compensation Mechanisms

Sympathetic Stimulation

- Increase in myocardial contractility and HR, maintaining CO despite reduced SV.

- Consequence: Less responsive and downregulation of β-receptors.

Expansion of Blood Volume

- Reduction in CO results in a fall in renal blood flow (RBF).

- RAAS system activation.

- Increased Na and H2O retention, increased LVEDV.

- Opposed by ANP and BNP.

Treatment Recommendations

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Anaesthetic Management

General Approach to Heart Failure

Baseline Assessment

- Functional Status: NYHA classification.

- Cardiac Function:

- Ejection Fraction (EF): HFrEF vs HFpEF.

- Diastolic dysfunction (grade and filling pressures).

- Biomarkers: NT-proBNP or BNP.

- History of previous decompensations.

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

- Subtypes:

- HFrEF (reduced EF).

- HFpEF (preserved EF).

- Underlying Cardiac Pathology:

- Dilated cardiomyopathy.

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy.

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Complications and Comorbidities

- Renal Dysfunction

- Electrolyte Abnormalities: Secondary to diuretics or disease progression.

- Arrhythmias: Atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

- Valvular Heart Disease: Common in chronic HF.

- Thromboembolism: Increased risk due to low flow states.

- Coexisting Diseases: Diabetes, COPD, hypertension, obesity, OSA.

Medical Therapy Review

- Ongoing Treatment:

- Beta-blockers.

- ACEi/ARB/ARNI.

- Mineraloorticoid receptor antagonists.

- SGLT2 inhibitors.

- Anticoagulants (if indicated).

- Antiarrhythmic drugs.

- Devices:

- CRT, ICD—note pacing dependency.

Preoperative Optimisation

- Medication Optimisation: Ensure continuation or safe weaning if needed.

- Volume Status: Achieve euvolaemia.

- Correction of:

- Anaemia.

- Electrolyte imbalances (especially K+, Mg²⁺).

- Malnutrition.

- Lifestyle: Smoking cessation, weight control, alcohol moderation.

- Control of Comorbidities: Diabetes, hypertension, infections, etc.

Anaesthetic Goals

- Maintain Myocardial Oxygen Supply–Demand Balance:

- Avoid tachycardia and hypertension.

- Maintain adequate oxygenation and haemoglobin.

- Reduce Myocardial Workload:

- Prevent excessive preload or afterload.

- Use vasodilators, inotropes judiciously.

- Preserve Coronary Perfusion Pressure (CPP)

- Avoid hypotension.

- Tailor induction and maintenance agents accordingly.

Haemodynamic Targets

-

General Principles:

- Maintain sins rhythm where possible.

- Aggressive treatment of arrhythmias—especially in HFpEF.

-

HFrEF:

- Avoid excessive afterload.

- Inotropic support may be required.

-

HFpEF:

- Rigid ventricles—sensitive to volume shifts.

- Maintain preload, avoid tachycardia.

- Tight control of blood pressure.

Preoperative

History

- Evidence of decompensation within 6 months of surgery is associated with increased risk of death post-operatively.

Investigations

- FBC, UCE, CMP, Glucose, LFT’s, TSH, HIV.

- ProBNP: Measurement of BNP or NT-proBNP is useful for establishing prognosis or disease severity in chronic HF.

- Cardiac troponin: Useful for establishing prognosis or disease severity in acutely decompensated HF.

- ECG and Echo.

Optimization

- Continue all meds except for ACE-I.

Preoperative Summary

- Full history and examination.

- Functional classification of heart failure.

- Risk stratification according to RCRI.

- 12-lead ECG: Recommended in patients with active CVS signs/symptoms, especially if high-risk surgery.

- CXR: Not routinely recommended.

- Echo: Not recommended in chronic stable HF. Needed to assess the degree of systolic/diastolic function if signs/symptoms of worsening HF.

- Decompensated HF (NYHA IV): Postpone surgery and refer to a cardiologist for optimization.

- Cardiac biomarkers: BNP monitoring recommended in high-risk patients.

- Pre-hab: Supervised aerobic exercise pre-op may improve mortality and cardiac structure/function.

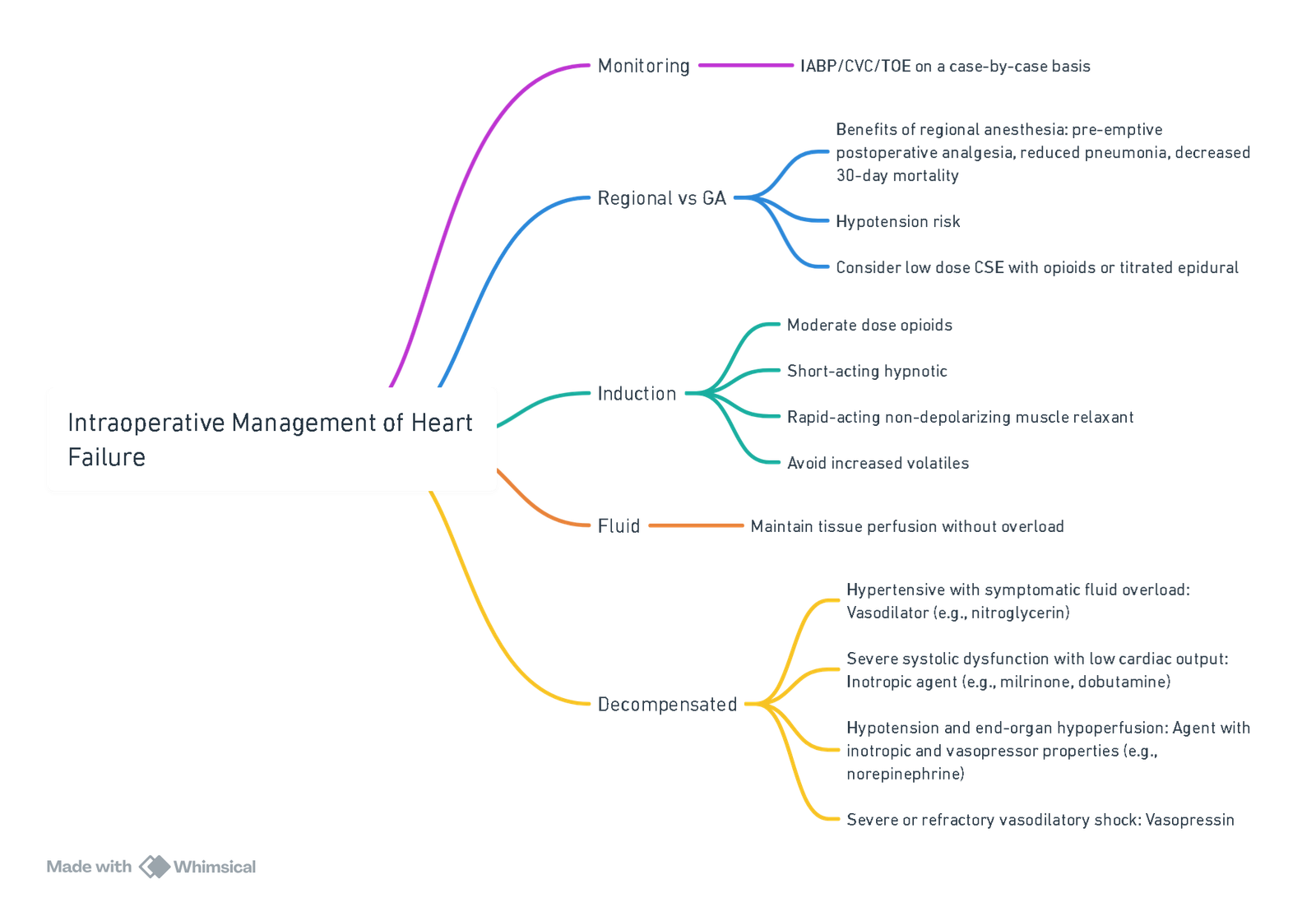

Intraoperative

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

- Local or regional anesthesia should be offered for minor peripheral procedures where possible.

- The poorly compliant ventricle must be given the opportunity to fill in diastole, requiring a higher than usual central venous pressure, avoidance of tachycardia, and aggressive treatment of arrhythmias.

- Maintain contractility with agents like milrinone due to beta receptor downregulation from chronic beta blocker use.

- Counter vasodilatation with noradrenaline.

- Minimize fluid load while preventing hypovolemia to avoid tachycardia.

- Invasive monitoring and cardiac output measurement should be considered for major surgery.

Postoperative

- HF patients do not tolerate artificial ventilation well.

- Postoperative pain control is essential to reduce tachycardia.

- Supplemental oxygen should be provided.

- Early mobilization is important.

- Careful fluid balance is required.

- Avoid NSAIDs to prevent further renal insult.

- Reintroduce ACE inhibitors as soon as possible. If omitted for more than 3 days, restart at a lower dose to avoid hypotension.

- Consider a low threshold for ICU or HDU admission.

Links

- Cardiac physiology

- Cardiac for non-cardiac surgery

- Valvular heart disease

- Off Pump CABG

- Ischaemic heart disease

- Pulmonary Hypertension

References:

- Kevin, L. G. and Barnard, M. (2007). Right ventricular failure. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care &Amp; Pain, 7(3), 89-94. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkm016

- Ibrahim, I. R. and Sharma, V. R. (2017). Cardiomyopathy and anaesthesia. BJA Education, 17(11), 363-369. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkx022

- Godfrey, G. E. P. and Peck, M. (2016). Diastolic dysfunction in anaesthesia and critical care. BJA Education, 16(9), 287-291. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkw007

- Reddi, B. A. J., Shanmugam, N., & Fletcher, N. (2017). Heart failure—pathophysiology and inpatient management. BJA Education, 17(5), 151-160. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkw067

- Chambers D, Huang CLH, Matthews G. Basic physiology for anaesthetists. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2015. 447 p. Chambers et al. – 2015 – Basic physiology for anaesthetists.pdf

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- Anaesthesia and Heart failure. Myburgh AUCT Refresher 2016

Summaries:

Heart failure

Right heart failure- video

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “af52df51-ad57-47bb-aec0-775eedec1646”