- Accidental Awareness During General Anaesthesia (AAGA)

- Awareness VIVA

- 1. Building Rapport & Setting the Scene (3 marks)

- 2. Information Gathering–Previous Event (3 marks)

- 3. Explains Nature of Prior Event (4 marks)

- 4. Discusses Awareness Under General Anaesthesia (3 marks)

- 5. Preventive Strategies for Upcoming Surgery (3 marks)

- 6. Communication Skills (4 marks)

- 7. Handles Patient Questions & Concerns (3 marks)

- 8. Structure & Professionalism (2 marks)

{}

Accidental Awareness During General Anaesthesia (AAGA)

Definition & Incidence

- AAGA: Explicit recall of intra-operative events under intended general anaesthesia—e.g., sounds, pressure, pain, paralysis.

- Incidence: Approximately 1:1,000 in structured studies like NAP5, ranging from 1:600 to 1:17,000 depending on methodology.

Sedation Depth Monitoring

| Technique | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomic/Somatic signs (BP, HR, tears) | Readily available | Low specificity |

| Movement/EMG | Simple | Blocked by NMB, not reliable |

| Isolated Forearm Technique | Detects consciousness during paralysis | Research tool only |

| Processed EEG (BIS, Entropy) | Quantifies sedation | Affected by EMG, NMB |

| Burst suppression | Indicates profound depth | Not protective from awareness |

- Key trial: BALANCE trial showed no mortality or major outcome differences by targeting BIS 50 vs 35—even though burst suppression depth varied.

Risk Factors for AAGA

- Emergency or obstetric procedures

- Rapid-sequence induction

- Use of neuromuscular blockers

- Obesity, difficult airway

- Interruption in anaesthetic delivery (e.g., during transport)

- Junior anaesthetist involvement

- Out-of-hours surgery

- Previous awareness

- Cardiac/thoracic surgery

- Young adult age (but not infants)

Clinical Evidence and Trials

| Trial | Design | Findings |

|---|---|---|

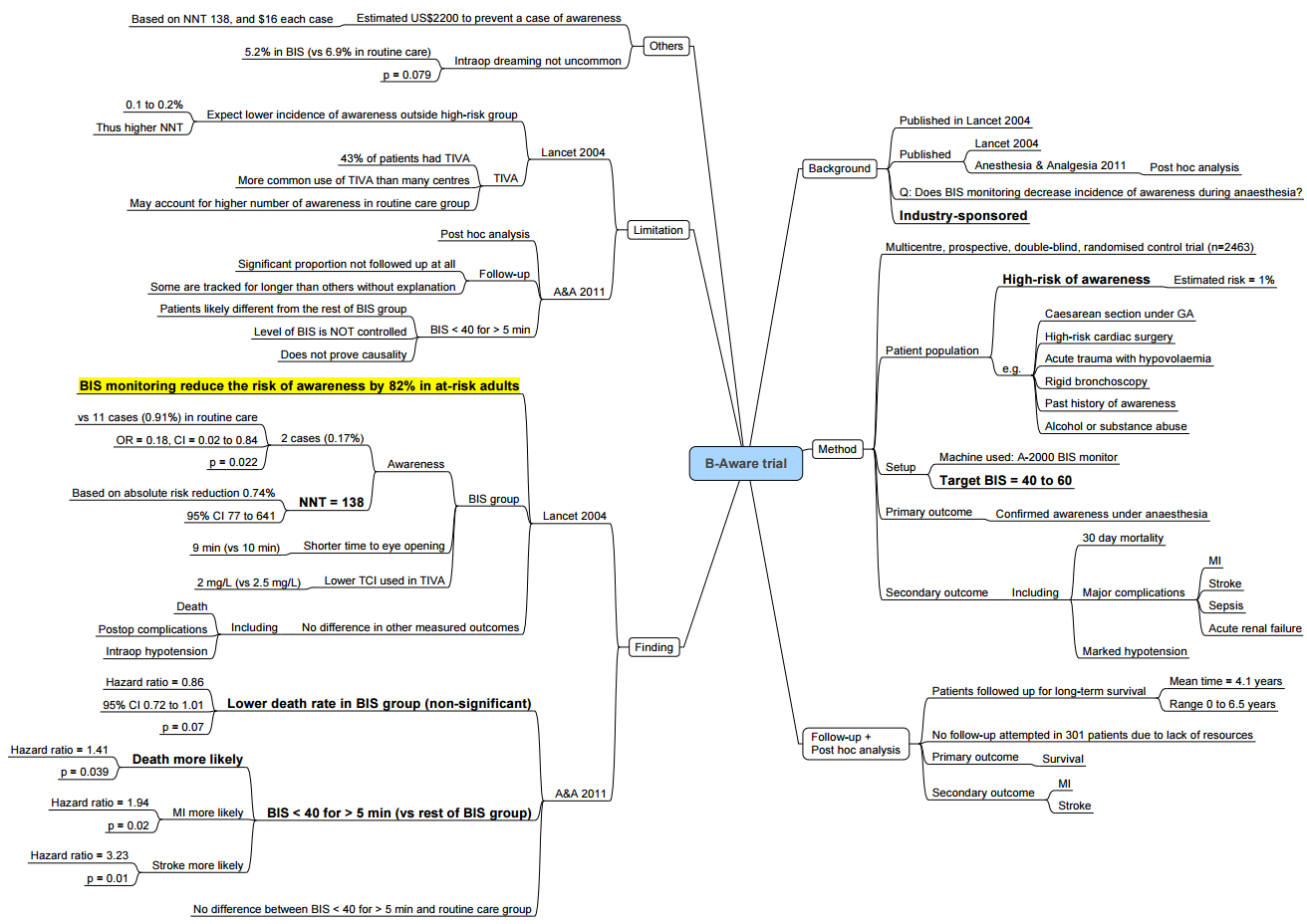

| B‑Aware (2004) | BIS 40–60 vs routine | Awareness 0.17% vs 0.91%; ARR 0.74%, NNT ≈ 697 |

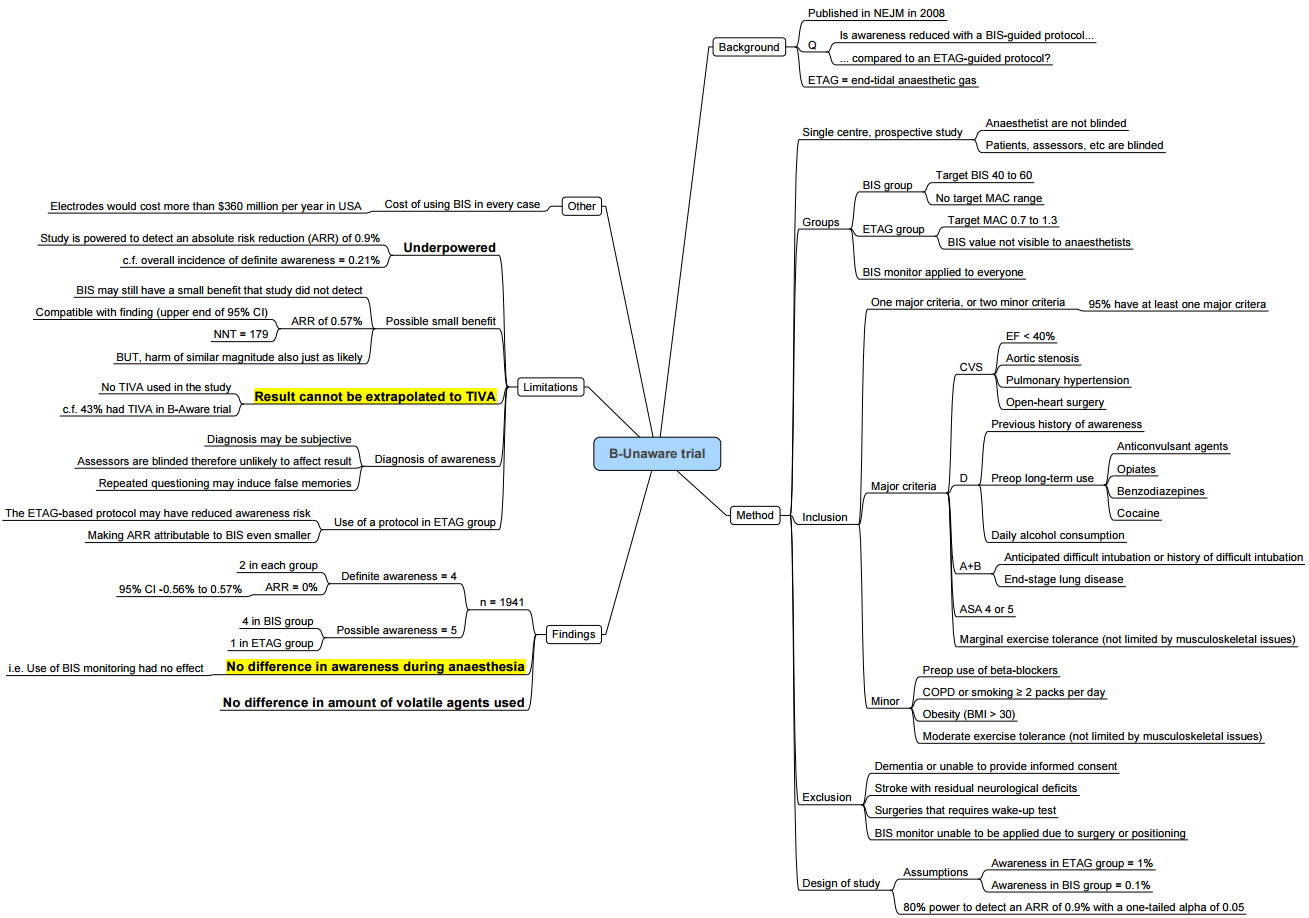

| B‑Unaware (2008) | BIS vs MAC-targeted volatile | No difference in awareness (0.21% both) |

| BAG‑RECALL (2011) | BIS vs MAC | No significant difference; BIS 0.28%, MAC 0.07% |

| MACS (2012) | BIS-guided vs routine care | No impact on awareness; trial stopped early |

| NAP5 (2014) | UK/Ireland survey | Overall incidence ~1:19,600; cardiothoracic procedures ~1:8,333; 41% had lasting psychological impact |

Prevention Strategy

Preoperative

- Identify high-risk groups

- Pre-op counselling with reassurance

- Premedicate (e.g., benzodiazepines) to reduce risk (not universally applied

Intraoperative

- Maintain age-adjusted MAC > 0.7

- Use processed EEG (BIS or entropy) for TIVA or NMB cases

- Monitor drug delivery and avoid interruptions

- Titrate NMB closely with objective monitoring

- Use infusion pumps with safety features

Postoperative

- Ask using the Modified Brice questionnaire in PACU and again within 24–72 hours

Management if Awareness Occurs

- Convene independent witness (colleague)

- Document event thoroughly

- Provide psychological support at 24 hours and 2 weeks; consider PTSD referral

- Report incident as a critical event

Patient Survey: Modified Brice Questions

- Last memory before sleep?

- First memory after waking?

- Any recollection during anaesthesia?

- Did you dream?

- Worst part of the experience?

- Helps distinguish awareness vs dreaming and assess patient distress.

Impacts of Awareness

- Short-term: anxiety, nightmares, flashbacks

- Long-term: PTSD, sleep disturbances, fear of future anaesthesia, medical avoidance

Clinical Recommendations

- Use depth-of-anaesthesia monitoring (BIS/entropy) in high-risk cases

- Keep volatile MAC ≥ 0.7 when used

- Ensure safe drug delivery—avoiding disconnections/delays

- Maintain vigilance during induction, emergence, transport phases

- Use postoperative screening (Brice tool) to detect and manage AAGA early

Awareness VIVA

Scenario: Counselling a patient with a past experience of awareness during a surgeon-led gastroscopy under midazolam, now scheduled for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy under general anaesthesia.

1. Building Rapport & Setting the Scene (3 marks)

- Greet the patient, introduce myself and my role as the anaesthetist.

- Explain: “I’d like to talk about your previous experience during your gastroscopy and discuss how we can minimise the risk of anything similar happening again.”

- Acknowledge their prior distress: “I understand that this was very distressing for you, and it’s completely reasonable to feel anxious before your next surgery.”

2. Information Gathering–Previous Event (3 marks)

- Use the Brice Questionnaire (or similar) to explore awareness:

- “What was the last thing you remember before going to sleep?”

- “What was the first thing you remember after waking?”

- “Do you remember anything in between?”

- “Did you have any dreams or sensations?”

- Clarify that the previous procedure was a surgeon-led gastroscopy using midazolam only, without an anaesthetist.

- Establish what they experienced (e.g., hearing voices, feeling discomfort, anxiety, partial recall).

3. Explains Nature of Prior Event (4 marks)

- Differentiate the event:

- “It sounds like your experience was due to inadequate sedation rather than true intraoperative awareness under general anaesthesia.”

- Explain contributing factors:

- “Midazolam causes sedation and some amnesia but doesn’t guarantee complete unconsciousness.”

- “Because there was no anaesthetist and the sedation may have been light, your awareness was not unexpected.

- Reassure:

- “You were not given any muscle relaxants or anaesthetic agents that cause full paralysis, so your safety wasn’t compromised in that regard.”

4. Discusses Awareness Under General Anaesthesia (3 marks)

- Define:

- “Awareness under general anaesthesia refers to a patient becoming conscious during surgery and having recall of events, which can be distressing.”

- Incidence

- “This occurs in about 1–2 cases per 1000 general anaesthetics.”

- Risk Factors:

- Previous awareness

- Equipment malfunction

- Emergency surgery

- Hypotension requiring lighter anaesthesia

- Elderly patients or those with altered physiology

- Acknowledge:

- “Having experienced awareness before slightly increases your risk, but we can take steps to greatly reduce it.”

5. Preventive Strategies for Upcoming Surgery (3 marks)

- Ensure continuous anaesthetist presence throughout the procedure.

- Use depth of anaesthesia monitoring (e.g., BIS or EEG-based monitoring) to titrate drug delivery.

- Conduct thorough equipment checks, ensure alarms are functioning, and confirm drug availability.

- Provide adequate analgesia and amnestic drugs.

- Arrange postoperative follow-up to address any concerns

6. Communication Skills (4 marks)

- Use open-ended questions: “How has this experience affected your confidence in undergoing surgery again?”

- Reflective listening and empathy: “It’s completely understandable to feel nervous—what you went through was very real.”

- Avoid minimising language (e.g., not saying “That’s rare, don’t worry”).

- Use simple language:

- “We’ll be closely watching your brain activity to ensure you’re deeply asleep.”

- Check understanding regularly: “Does that make sense so far? Any part you’d like me to explain more?”

7. Handles Patient Questions & Concerns (3 marks)

- “Will it happen again?”

- “The risk is low, and we are taking several steps to ensure it doesn’t.”

- “How will you know I’m asleep?”

- “We use monitors that assess depth of sleep and constant clinical observation.”

- “What if the equipment fails?”

- “We regularly test all equipment, and we have backups and alarms for every critical system.”

- Offer pre-medication (e.g., anxiolytics) or psychological support if desired.

- Acknowledge uncertainty when appropriate: “There is always a very small risk, but I’ll do everything I can to minimise it.”

- Offer further resources: “I can provide written information or refer you for a second opinion if you wish.”

8. Structure & Professionalism (2 marks)

- Logical and clear structure:

- Set the agenda → gather history → explain past → outline risks → propose strategy → answer concerns → summarise.

- Summarise:

- “To summarise: your previous experience was likely due to light sedation without anaesthetic drugs. Your upcoming surgery will be different—we’ll provide continuous monitoring, deeper anaesthesia, and post-op follow-up.”

- Invite further questions:

- “Do you have any other concerns you’d like to talk about?”

- Thank the patient for their time and openness.

BART

BE-UNAWARE

Links

References:

- Tasbihgou, S. R., Vogels, M. F., & Absalom, A. (2017). Accidental awareness during general anaesthesia–a narrative review. Anaesthesia, 73(1), 112-122. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.14124

- Kim, M. C., Fricchione, G. L., & Akeju, O. (2021). Accidental awareness under general anaesthesia: incidence, risk factors, and psychological management. BJA Education, 21(4), 154-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2020.12.001

- Pandit JJ, Cook TM, Jonker WR, et al. NAP5: Accidental awareness under general anaesthesia in the UK and Ireland. Anaesthesia. 2014;69(6):523–531.

- Myles PS, Leslie K, McNeil J, et al. BIS versus MAC for awareness prevention (BAG-RECALL). N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):591–600.

- Avidan MS, Zhang L, Burnside BA, et al. Anesthesia awareness and BIS (B‑Aware). N Engl J Med. 2004;350:637–646.

- Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC, Sigl JC. Intraoperative Bispectral Index monitoring and awareness (B‑Unaware). Anesthesiology. 2008;109(3):613–620.

- Abend NS, Stain SC. PTSD after awareness under anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(2):416–417.

- Bouafif‑Bossert MY, Bohnen NI. Depth of anesthesia monitoring: BIS and processed EEG in anaesthetic practice. BJA Educ. 2021;21(5):175–184.

- Everitt SJ, Management of intraoperative awareness. AAGBI Safety Guideline. 2020.

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “b01d6249-8cd2-40f1-bcf5-f10748ed4abf”