{}

Colorectal Surgery

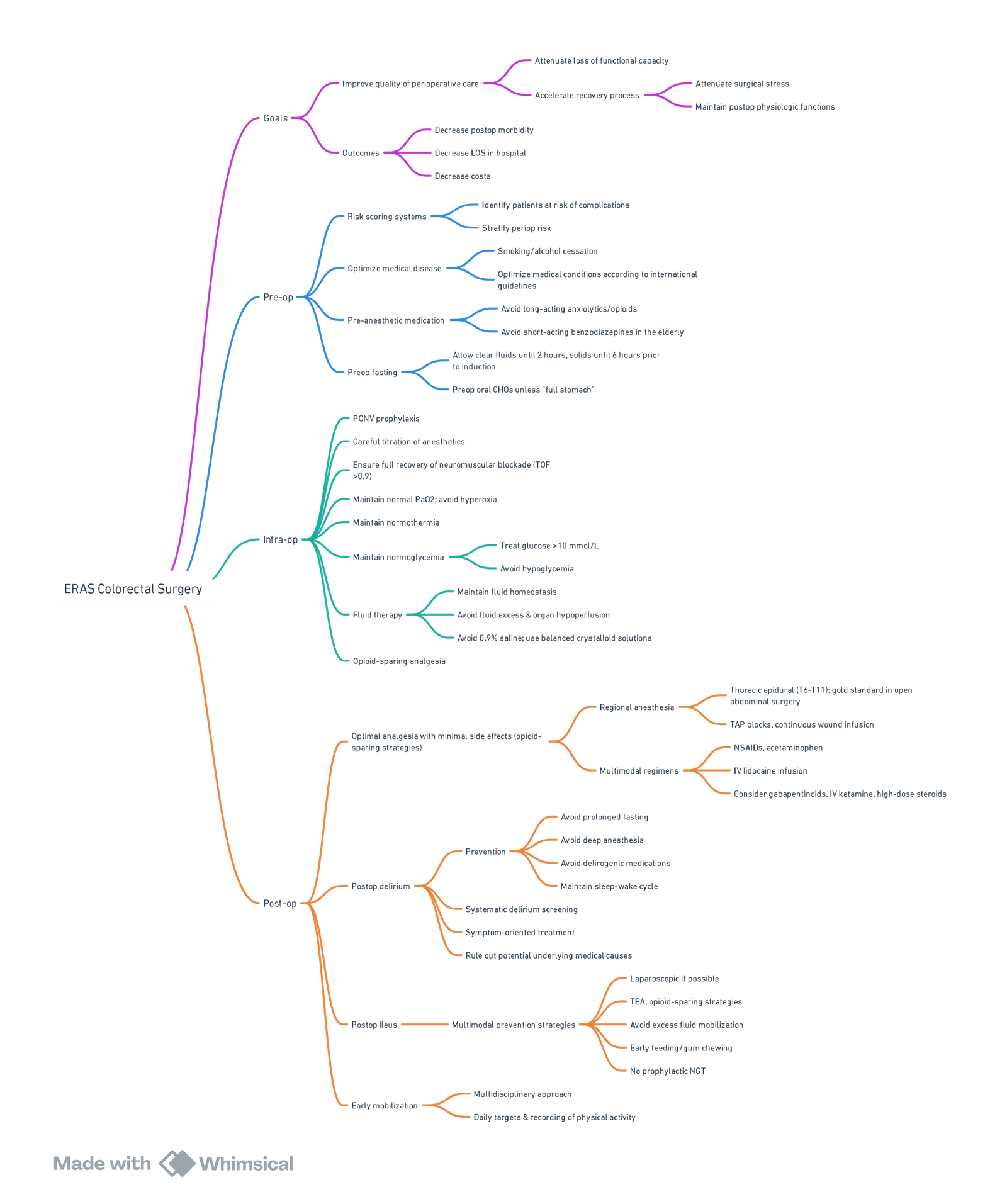

ERAS

Preoperative Patient Education

- Set Expectations

- Provide explicit written information at an appropriate literacy level.

- Specify daily goals for nutritional intake and ambulation in the perioperative period.

- Define discharge criteria and expected hospital stay.

Preoperative Risk Evaluation and Optimization

| Risk Evaluation | Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Function | ACC/AHA Guidelines: Apply as per standard protocol. |

| Revised Cardiac Risk | Follow established guidelines. |

| Cardiac Risk Calculator | Use validated tools for assessment. |

| METs | Assess functional capacity. |

| Renal Function | Acute Kidney Injury Risk Index: Assess risk and optimize accordingly. |

| Respiratory Function | ACP Guidelines: Follow the American College of Physicians guidelines. |

| Modified Clinical Pulmonary Infection Score | Apply for risk assessment and optimization. |

| Postoperative Pneumonia Risk Index | Utilize for evaluation. |

| Diabetic Patients | AACE/ADA Guidelines: Manage based on American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association guidelines. |

| HbA1c > 6.0% | Target exercise, weight loss, and glycemic control. |

| Anemia | ASA Recommendations: Optimize preoperative hemoglobin levels and apply perioperative blood management strategies. |

| Determine the cause of anemia | Address underlying causes. |

| Nutritional Status | Provide nutritional support based on risk evaluation. |

| Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS-2002) | Screen for nutritional risk. |

| Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) | Evaluate nutritional status. |

| Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) | Apply screening tool for assessment. |

| Nutritional Risk Index (NRI) | Assess and address nutritional deficits. |

| Frailty (Frailty Phenotype) | Implement prehabilitation strategies. |

| Weight loss, Weakness, Exhaustion, Slowness, Low Physical Activity | Identify and optimize frailty-related risks. |

| Smoking and Alcohol Abuse | Smoking Cessation: Implement a multidisciplinary approach, including preoperative counseling and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). |

| Beneficial effects seen after at least 3 weeks of abstinence | Aim for reduction of postoperative complications through extended abstinence. |

| Functional Capacity | Preoperative Exercise: Encourage exercise and prehabilitation. |

| METs, Walking Test, CPET | Use functional capacity assessments. |

| Secondary Adrenal Suppression | Continue steroids throughout the perioperative period. Administer stress doses in cases of hypotension unrelated to other causes. |

Anaesthetic Management

Preoperative Fasting and Preoperative Oral Carbohydrate Drinks

- Fasting Guidelines

- 2-hour fast for liquids and 6-hour fast for solids.

- Clear fluids are safe up to 2 hours before anesthesia induction.

- Oral Carbohydrate Drinks

- Administer 100 g (800 mL) of 12.5% complex carbohydrate (maltodextrin) the evening before surgery.

- Administer 50 g (400 mL) 2-3 hours before anesthesia induction.

- Benefits include decreased insulin resistance, reduced protein breakdown, improved muscle strength, and faster recovery.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

- Administer within 30-60 minutes before surgical incision.

- Recommended agents: cefazolin plus metronidazole or cefoxitin/cefotetan.

- Alternatives for allergies: gentamicin (5 mg/kg) and clindamycin (900 mg).

- For MRSA risk: use vancomycin with cefazolin.

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

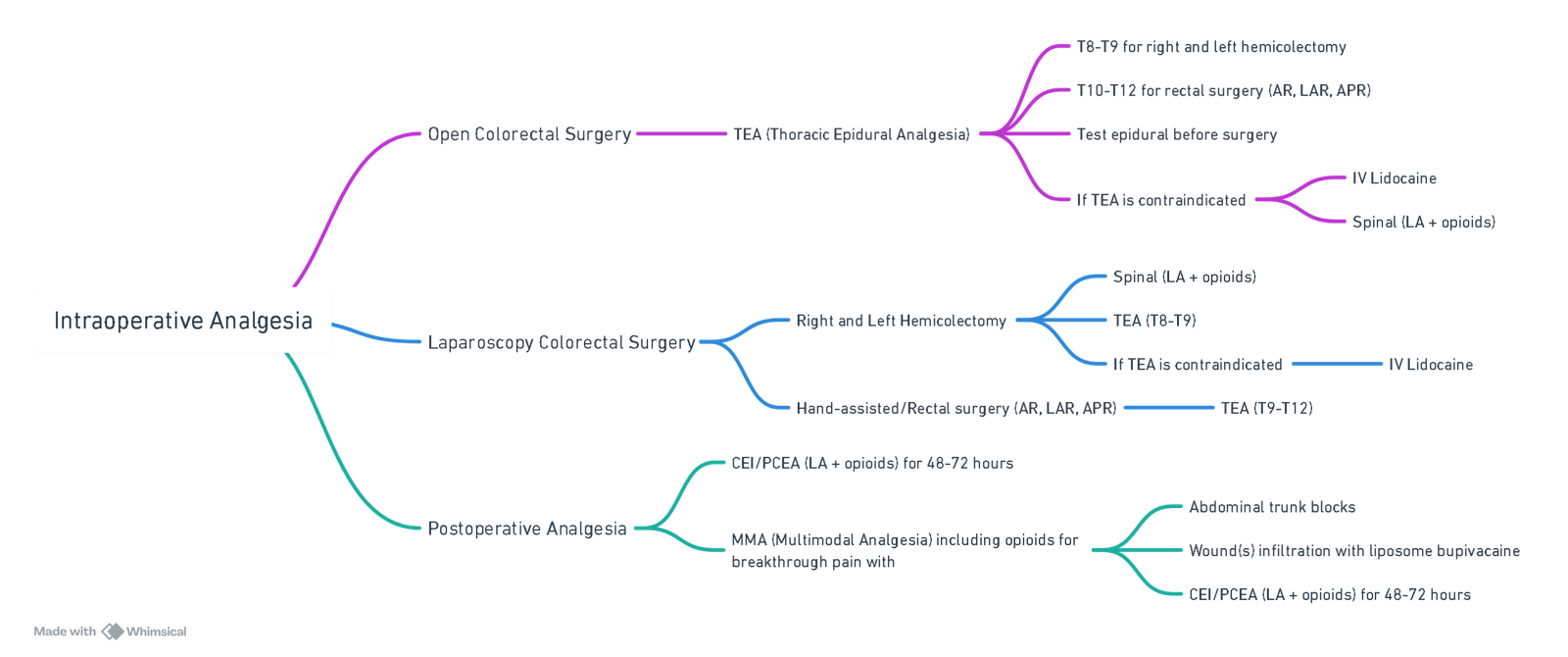

Analgesia

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Ventilation

- Use lung-protective strategies even in patients with normal lung function.

- Titrate FiO2 to optimal levels based on oxygen saturation, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, and serum lactates.

- High FiO2 (0.8) may benefit colorectal surgery patients.

Intraoperative Hemodynamic Management

- Prefer isotonic balanced solutions over 0.9% saline.

- Avoid large volumes of hydroxyethyl starch (HES).

- Individualize transfusion decisions based on clinical context and patient comorbidities.

Intraoperative Fluid Replacement

- Preoperative Fasting: Minimal intravascular volume reduction.

- Mechanical Bowel Prep: Avoid or manage with 1000-2000 mL if used.

- Epidural/Spinal Analgesia: Use vasopressors for neuraxial blockade-induced hypotension.

- Maintenance Fluids: Replace insensible losses with iso-oncotic crystalloids.

- Blood Loss Replacement: Use colloids or iso-oncotic crystalloids based on clinical estimation.____

| Intraoperative Fluid Replacement | Intravenous Fluid Administration: a Physiologic and Evidence-Based Approach (70 kg, Elective, No MBP, 2 h Fasting, 2 h Laparoscopic SR Surgery, EBL = 500 mL) |

|---|---|

| Preoperative fasting | Intravascular volume is minimally reduced after overnight fasting. 30% of patients do not have an intravascular preoperative deficit. |

| Mechanical bowel prep | Avoided in colonic surgery. 1000–2000 mL if MBP is used. |

| Preloading in patients receiving epidural or spinal analgesia | Intravenous fluids do not prevent hypotension induced by neuraxial blockade. Vasopressors are the first choice to treat hypotension induced by neuraxial blockade. |

| Intravascular volume expansion (anesthesia-related) | In normovolemic patients, intravenous fluids are not necessary and vasopressors are the first choice to treat hypotension induced by anesthesia. |

| Maintenance | Replacement of insensible losses (iso-oncotic crystalloids, avoid 0.9% normal saline). Insensible loss during maximal bowel exposure are not higher than 1 mL/kg/h. Open surgery: 3–5 mL/kg/h. Laparoscopic surgery: <3 mL/kg/h. GDT: in high-risk patients or in patients undergoing surgery with extensive blood loss (>7 mL/kg). |

| Third space | Nil. A primarily fluid-consuming third space has never been identified. |

| Urine/GI loss | 1:1 iso-oncotic crystalloids according to clinical estimation. |

| Blood/type 2 shifting | 1:1 colloid, or 3:1 iso-oncotic crystalloids (in patients with AKI). Intravascular deficit should be measured (GDT high-risk patients). GDT: in high-risk patients or in patients undergoing surgery with extensive blood loss (>7 mL/kg). |

| Total (mL) | 1000–3200 |

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV)

- Employ multimodal prophylaxis strategies.

- Use regional analgesia, adequate hydration, and antiemetics.

Glycemic Control

- Maintain preoperative HbA1c <6.0% to reduce hyperglycemia risk.

- Target random blood sugar <10 mmol/L perioperatively.

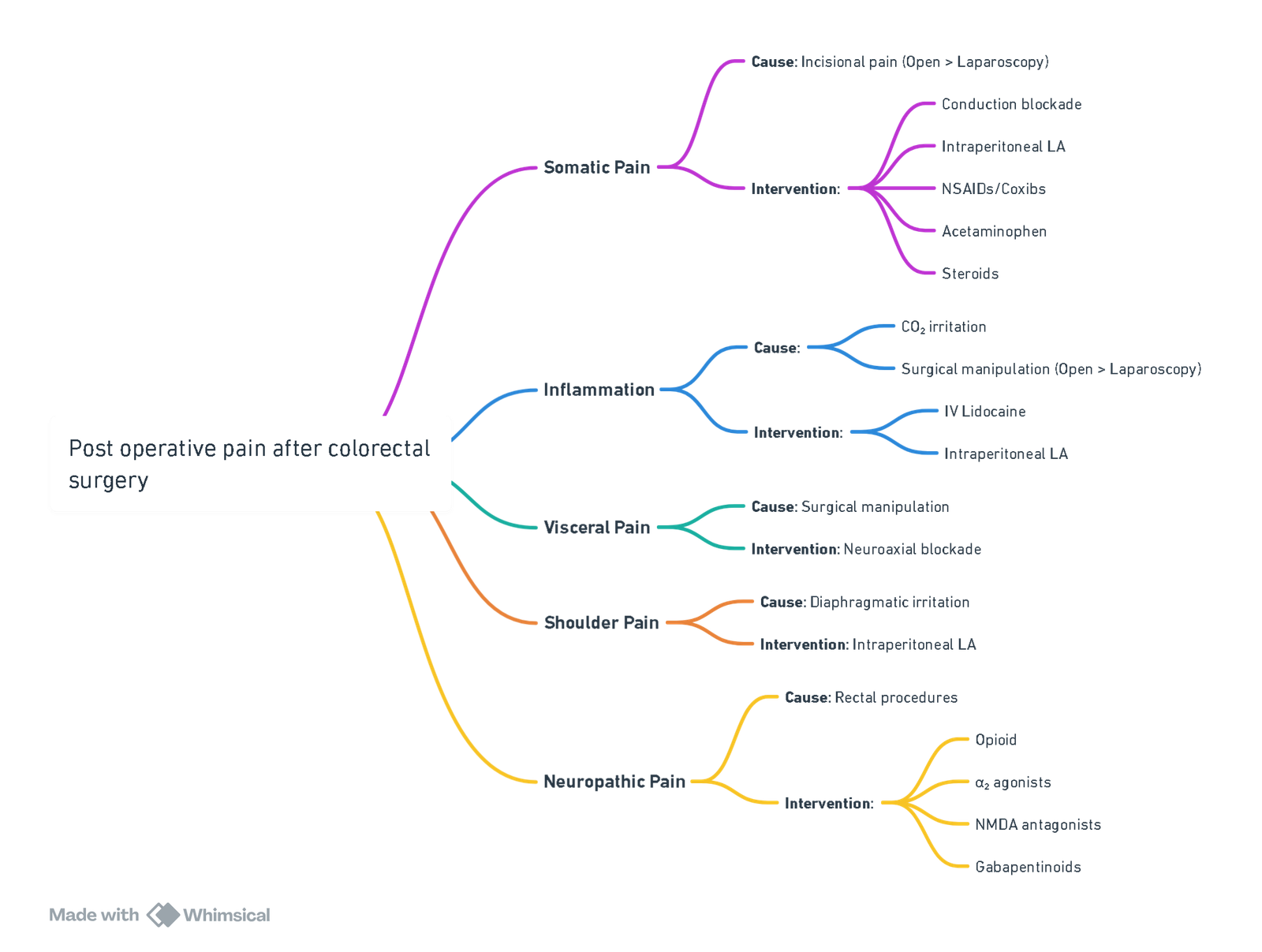

Postoperative Pain and Analgesia

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Common Analgesic Techniques

| Analgesia | Technique and Dose | Comments and Potential Complications |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracic epidural analgesia (TEA) | T8-T9 for R and L hemicolecto T10-T12 for sigmoid-rectal surgery Intraoperative: 5 mL bupivacaine 0.25%-0.5% intermittent boluses or 5 mL/h continuous infusion Postoperative (CEI or PCEA): bupivacaine 0.05%-0.125% or ropivacaine 0.2%, with fentanyl 2-3 μg/mL or hydromorphone 5-7.5 μg/mL |

Arterial hypotension Bladder dysfunction Lower limb weakness Consider adding epidural epinephrine (2 μg/mL) if epidural block is patchy or weak |

| Spinal analgesia | 10 mg 0.5% isobaric bupivacaine or 15 mg 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine Intrathecal morphine: <70 y 200-250 μg >70 y 150 μg |

Arterial hypotension Pruritus Bladder dysfunction Respiratory depression |

| Intravenous lidocaine | Intraoperative and in PACU: 1.5 mg/kg bolus or within 30 min before induction of anesthesia followed by 2 mg/kg/h until the end of surgery. Infusion can be extended in PACU |

Local anesthetic toxicity Intravenous lidocaine infusion requires continuous cardiovascular monitoring |

| Continuous wound infusion of local anesthetic | In most studies, a multihole catheter is positioned along the surgical incision between the peritoneum and the fascia (preperitoneal) Ropivacaine 0.2% 8-10 mL in the wound followed by Ropivacaine 0.2% 5-8 mL/h for 48 h |

Local anesthetic toxicity The ideal anatomic location where multihole catheters are to be placed has not yet been clearly determined |

| TAP block | US-guided or surgically performed Subcostal approach (upper abdominal surgery): Unilateral or bilateral Single shot 15-20 mL of 0.25%-0.375% bupivacaine or levobupivacaine Intermittent boluses through multihole catheters 15-20 mL of local anesthetic every 6 h per site Continuous infusion through multihole catheters 6-8 mL/h of 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine Lateral approach (lower abdomen): Single shot 15-20 mL of 0.25%-0.375% bupivacaine or levobupivacaine Intermittent boluses through multihole catheters 15-20 mL of local anesthetic every 6 h per site Continuous infusion through multihole catheters 6-8 mL/h of 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine Posterior approach (lower abdomen): Single shot 15-20 mL of 0.25%-0.375% bupivacaine or levobupivacaine Intermittent boluses through multihole catheters 15-20 mL of local anesthetic every 6 h per site Continuous infusion through multihole catheters 6-8 mL/h of 0.25% bupivacaine or 0.2% ropivacaine |

Few complications have been reported, especially when the TAP block is performed under direct US guidance; these include intrathecal and intraperitoneal injections. Local anesthetic toxicity should also be considered, especially when multiples or continuous TAP blocks are performed. Pain: Reduced static pain score and opioid consumption |

| Rectus sheath block | US-guided Bilateral Single shot 15-20 mL of 0.25%-0.375% bupivacaine or levobupivacaine Intermittent boluses through a multihole catheter 15-20 mL of 0.25% bupivacaine or levobupivacaine per site |

Provide analgesia for the whole midline of the abdomen Shorter analgesic effect than TAP block |

| Liposomal bupivacaine | 266 mg in 40 mL 0.9% normal saline | Use in the context of MMA phase IV studies. Limited evidence |

ERAS Elements under the Control of the Anaesthesiologist

| ERAS Elements Under Direct Control of Anesthesiologist | Key Points |

|---|---|

| Patient education | Preoperative patient education is an essential component of any ERAS program. It is important to specify the active role the patient is expected to play in the perioperative period. Written or visual information at an appropriate literacy level, specifying daily goals for nutritional intake and postoperative ambulation, discharge criteria, and expected hospital stay should be provided. |

| Preoperative evaluation, risk stratification, and optimization | Optimize preoperative conditions associated with poor outcomes, including patient comorbidities, nutritional status, anemia, and functional capacity. Intense smoking cessation interventions, including NRT and individual counseling for at least 3-4 weeks before surgery to reduce postoperative complications. More studies evaluating the role of optimizing preoperative conditions to a point to delay surgery in patients undergoing oncologic colorectal surgery are warranted. |

| Preoperative fasting and preoperative oral carbohydrate (CHO) drinks | There is no scientific evidence to support the policy of routine NPO after midnight. Fasting from midnight increases insulin resistance and depletes glycogen reserves. These effects are magnified by the stress response induced by surgery. Current preoperative fasting guidelines for adult patients undergoing elective surgery recommend a 2-hour fast for liquids and a 6-hour fast for solids. Preoperative oral CHO drinks are safe, reduce insulin resistance, and improve patients’ well-being. |

| Antibiotic prophylaxis | Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing colorectal surgery must cover aerobic and anaerobic flora, according to international guidelines. Antibiotic prophylaxis should be completed within 1 hour before surgical incision. Intraoperative dosing depends on the half-life of the antibiotic used and on the surgical blood loss. It should not last more than 24 hours. |

| Premedication | Patients should not routinely receive anxiolytic agents. The use of short-acting anxiolytic agents is advised to facilitate invasive procedures uncomfortable for patients (epidural, arterial lines, etc.). Benzodiazepine should be avoided in patients older than 65 years. |

| Anesthetic agents and cerebral monitoring | The use of short-acting inhalation or intravenous agents is advised. TIVA with propofol should be considered in patients at high risk of PONV. Avoid N₂O. Monitoring depth of anesthesia reduces anesthetic requirement, minimizes anesthetic hemodynamic effects, and can be particularly useful in elderly patients to facilitate recovery. |

| Attenuation of surgical and inflammatory stress | Attenuation of surgical stress is a key element in enhancing recovery. The use of regional anesthesia techniques, glucocorticoids, intravenous lidocaine, and prevention of hypothermia has been shown to attenuate the stress response associated with surgery. |

| Intraoperative analgesia | Regional anesthesia techniques, including TEA and spinal anesthesia, reduces anesthetic and systemic opioid requirements. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of intravenous lidocaine have been shown to reduce anesthetic and opioid consumption, reduce opioid side effects, and hasten recovery. Ketamine, α₂-agonists, and other analgesic adjuvants have shown opioid-sparing properties, but their role in colorectal patients and in the context of an ERAS program has not been studied. |

| Intraoperative ventilation | Intraoperative lung-protective ventilation with low tidal volumes (VT = 6-8 mL/kg, IBW), adequate PEEP (6-10 cmH₂O), and lung recruitment manoeuvres is beneficial (reduced inflammation and better outcomes) even in patients with uninjured lungs undergoing abdominal surgery. Intraoperative oxygen therapy (FiO₂) should be titrated to the most favorable concentration that ensures optimal tissue oxygenation based on the evaluation of oxygen saturation, arterial partial oxygen pressure (Pao₂/FiO₂ ratio), and serum lactates. The use of intraoperative high-inspired oxygen fraction (FiO₂ = 0.8) to prevent surgical-site infections has shown conflicting results. However, patients undergoing colorectal surgery might particularly benefit from this intervention. |

| Myorelaxation | Short or intermediate-acting muscle relaxants are recommended. Adequate muscle relaxation is essential to guarantee optimal surgical conditions, especially during laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Neuromuscular blockade must be monitored (TOF, double-burst, or tetanic stimulation pattern) throughout the intraoperative period. Quantitative assessment (acceleromyography) of neuromuscular function is more reliable than qualitative assessment (visual or tactile) in identifying patients with residual paralysis. |

| Prevention of hypothermia | Core temperature must be monitored and hypothermia (core temperature <36°C) avoided. |

| Intraoperative hemodynamic management | In colorectal patients treated within an ERAS program, minimization of preoperative fasting, avoidance of MBP, a more rational and evidence-based intravenous fluid administration, and early resumption of oral intake have significantly reduced the amount of perioperative intravenous fluids needed. GDT seems beneficial in high-risk patients and in patients undergoing surgery with extensive blood loss (>7 mL/kg). Iso-oncotic crystalloid solutions should be used and 0.9% saline solutions avoided. Colloid should be avoided in patients with preexisting renal diseases and in septic patients. Anemia thresholds triggering blood transfusions cannot be currently recommended, as hemoglobin levels resulting in tissue hypoxia are patient-specific. The decision to transfuse blood should be made on an individual basis, depending on the clinical context, serum lactate levels, central oxygen venous saturation, and patient comorbidities. |

| PONV prophylaxis | PONV prophylaxis is an essential to facilitate early feeding. Patients at high risk of PONV can be identified. PONV prophylaxis guidelines must be followed. |

| Glycemic control | Hyperglycemia is associated with worse outcomes. Preoperative hemoglobin A₁c >6.0% can predict hyperglycemia and postoperative complications even in nondiabetic patients. Maintain glycemia <10 mmol/L. |

| Postoperative analgesia | The choice of the analgesia depends on the surgical approach (laparotomy or laparoscopy), the site of the surgical incision (midline, transverse, semicurve, or Pfannenstiel-like incision), the type of surgery (colon or rectum), and patient comorbidities. TEA remains the gold standard for postoperative pain control for patients undergoing open colorectal surgery. However, TEA increases the risk of arterial hypotension. Spinal analgesia with intrathecal morphine, abdominal trunk blocks, intravenous lidocaine, continuous wound infiltration of local anesthetic, and wound infiltration with liposome bupivacaine are valuable analgesic techniques, especially for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. A multimodal analgesic approach is recommended with the aim of providing optimal analgesia and reducing opioid consumption and side effects, with the ultimate goal of facilitating early feeding and early postoperative mobilization. |

Intestinal Transplant

Contraindications for Intestinal Transplantation

- Active infection

- History of malignancy (except non-melanoma skin cancer in the last 2 years)

- Congenital or acquired immune deficiencies

- Advanced neurological disorders

- Major psychiatric illness or non-compliant patient behaviour

- Any co-morbidity that would restrict life expectancy to less than 5 years

Conduct of Anaesthesia

Pre-op

Transplant Recipient Evaluation

Specialist Laboratory Studies

- Blood group and HLA tissue typing

- Trace elements and vitamin A, B6, D, and E levels

- Thrombophilia screening

- Urinalysis, culture, and 24-hour collection

- Serology including:

- CMV IgG

- Toxoplasma IgG

- EBV IgG

- HSV IgG

- HIV

- HBsAg

- HBsAb

- HCV

- Syphilis IgG

- VZV IgG

- MRSA screening swabs

Imaging

- Chest X-ray (CXR)

- Central vein mapping: magnetic resonance venography or Doppler ultrasonography

- +/- Angiographic studies

- Liver and abdominal ultrasonography

- CT scan abdomen and pelvis

- Small-bowel radiology (Barium or MR enteroclysis)

- Bone density scan

Cardiovascular Evaluation

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiography

- Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy

- +/- Coronary angiography

Other

- Pulmonary function tests

- Oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy

- Colonoscopy

- Liver biopsy

Monitors

- Two large-bore cannulae and preferably two separate arterial lines (radial and femoral).

- Central venous access, guided by pre-operative venographic studies, can be challenging.

- Teflon guide wires can be useful in difficult cases.

- Additional invasive monitoring (e.g., pulmonary artery flotation catheters, oesophageal Doppler, PiCCO, LIDCO, transoesophageal echocardiography) may be established preor post-induction depending on cardiovascular status.

- Thromboelastography (TEG)

- Cell saver

Positioning

- Patient is positioned supine with both arms either carefully positioned at the patient’s side or abducted to a maximum of 70° to prevent brachial plexus injury.

- Normothermia maintenance is challenging, using both above and below warming hot air overblankets, with the lower chest and abdomen exposed for surgical access.

Intra-op

- Anaesthesia should be managed by two or more experienced anaesthetists.

- Risk of aspiration mandates a rapid sequence induction in most patients.

- Post-operative analgesia can be managed by patient-controlled analgesia (fentanyl or morphine) or patient-controlled epidural analgesia (0.01% bupivacaine and 2-5 mg/ml fentanyl).

- Post-induction, a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g., meropenem 500 mg) is administered, repeated every 8 hours for 5 days.

- A nasogastric tube is inserted and secured to avoid postoperative displacement, which would require replacement under direct vision due to the risk of anastomotic disruption.

- A protective lung ventilation strategy with tidal volumes of 6-8 ml/kg and minimal positive end-expiratory pressure is recommended.

- Surgical retraction may significantly increase airway pressures.

Fluid and Electrolyte Management

- Tremendous fluid extravasation occurs throughout the procedure, with substantial bowel oedema from ischaemic reperfusion injury and third-space losses.

- Goal: haemodynamic stability and prevention or amelioration of abdominal viscera oedema, best achieved by a ‘conservative fluid strategy’ and judicious use of inotropes and vasopressors guided by cardiovascular monitoring.

- Balanced crystalloid infusion at 10 ml/kg/h for maintenance.

- Blood loss initially replaced with colloid, later with packed red cells to maintain haematocrit at 0.28-0.30, ensuring adequate oxygen delivery while preventing graft arterial thromboses.

Reperfusion Phase

- Infusion of methylprednisolone 500 mg over at least 30 minutes before intestine reperfusion. Avoid rapid infusion due to risk of dramatic cardiovascular instability.

- Ensure serum potassium <4 mmol before reperfusion.

- ‘Post-reperfusion syndrome,’ characterized by marked hypotension and cardiovascular instability, occurs in 47% of small-bowel transplants.

- Optimize cardiovascular status before reperfusion, and have appropriate fluids and vasoactive agents ready.

Links

- Upper GIT Surgery

- Lung resection

- Liver resection

- Organ protection

- Liver transplant

- Transplants and organ donation

References:

- Baldini, G. and Fawcett, W. (2015). Anesthesia for colorectal surgery. Anesthesiology Clinics, 33(1), 93-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anclin.2014.11.007

- Pichel, A. and Macnab, W. R. (2005). Anaesthesia for pancreas transplantation. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care &Amp; Pain, 5(5), 149-152. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mki040

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries

Fast-track-anaesthesia

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “707fd5ba-c3ad-4d23-bdb7-ad09fc8e928d”