- Summary

- Introduction

- Antepartum Haemorrhage

- Post Partum Haemorrhage

{}

Summary

Introduction

- Haemorrhage—antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum—remains the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide, accounting for approximately 27% of maternal deaths, with proportions exceeding 30% in sub‐Saharan Africa and South Asia.

- Global incidence of postpartum haemorrhage (blood loss > 500 mL after vaginal delivery or > 1 000 mL after caesarean delivery) is 10.8%, with severe cases (> 1 000 mL) in 2.8% of deliveries.

General Anaesthetic Considerations for Placental Pathology

Pre‐operative Assessment and Preparation

- Full blood count, coagulation profile, group and save, cross‐match (minimum 4 units).

- Ensure availability of cell salvage, rapid infusers and blood‐warming devices.

- Optimise antenatal anaemia with intravenous iron or erythropoietin where indicated.

Pharmacological Haemostatic Strategies

- Tranexamic acid (TXA): 1 g IV infusion over 10 minutes within 3 hours of bleeding onset; repeat 1 g if bleeding persists after 30 minutes (WOMAN trial).

Choice of Anaesthetic Technique

- Neuraxial anaesthesia (spinal or combined spinal–epidural) is preferred for elective lower-segment caesarean section in placenta previa when coagulation parameters are normal:

- Associated with ~20% lower estimated blood loss and ~30% fewer transfusions compared with general anaesthesia.

- Conversion to general anaesthesia occurs in 10–20% of cases; counsel patients accordingly.

- General anaesthesia indicated for haemodynamic instability, ongoing massive haemorrhage or coagulopathy; rapid-sequence induction recommended

Antepartum Haemorrhage

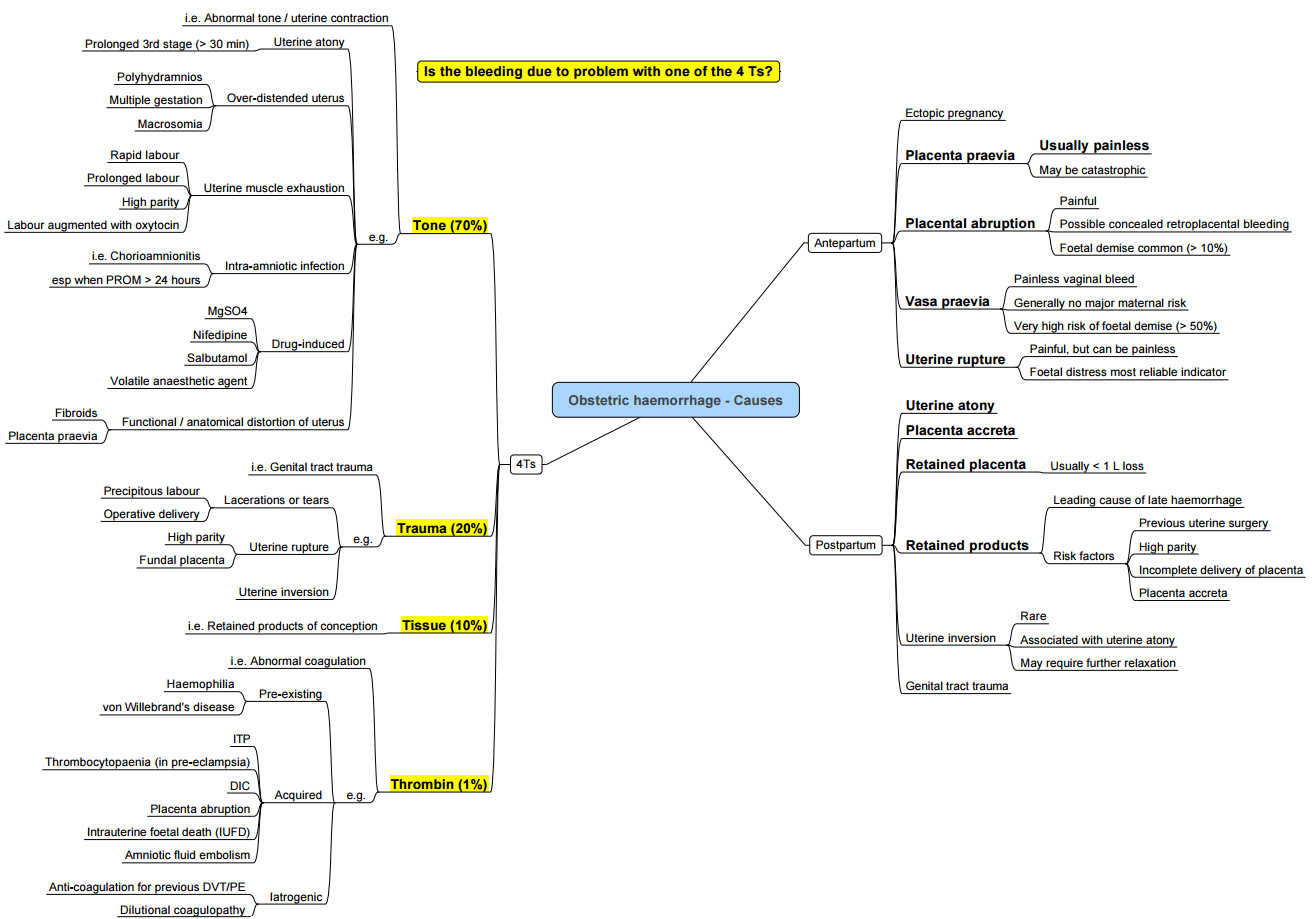

- Bleeding after 20 weeks’ gestation and prior to delivery complicates ≈ 3–5% of pregnancies. Main causes:

- Placenta previa

- Placenta accreta spectrum

- Placental abruption

- Vasa praevia

- Uterine rupture

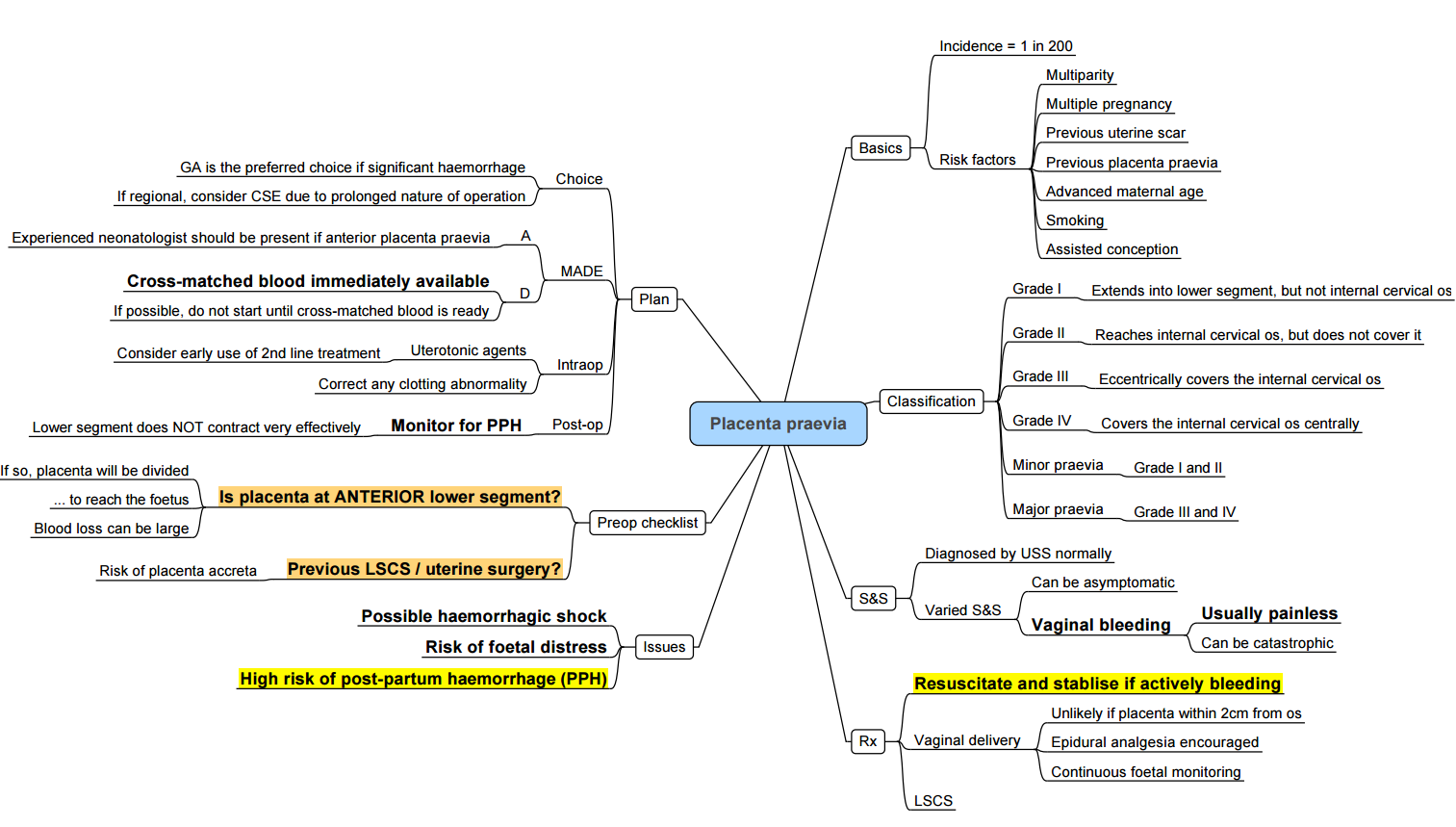

Placenta Previa

Definitions and Classification

- Placenta previa: placental tissue reaches or covers the internal cervical os.

- Types:

- Major (complete coverage)

- Partial

- Marginal (within 2 cm of os)

- Low-lying (2–5 cm from os in the third trimester)

Risk Factors

- Previous caesarean section

- Advanced maternal age

- Multiparity

- Multiple gestation

- Smoking

Diagnosis and Monitoring

- Transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound at 18–20 weeks; repeat at 32 weeks to assess placental migration.

- Digital vaginal examination contraindicated until placenta previa excluded

Management

- Elective caesarean at 37 weeks in a multidisciplinary centre.

- Neuraxial anaesthesia if stable (see Section 1.3).

- Prepare for massive transfusion, cell salvage and invasive monitoring.

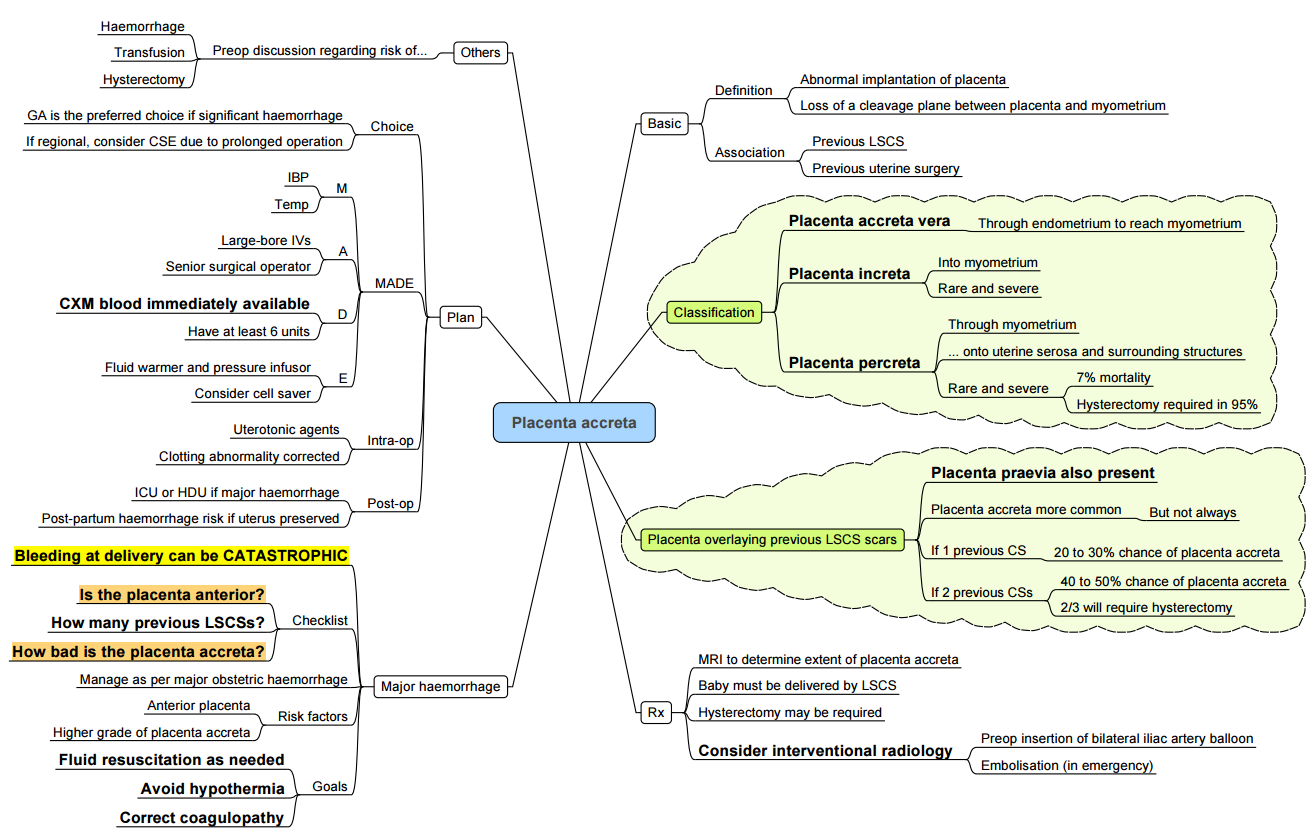

Placenta Accreta Spectrum

Incidence and Risk Factors

- Incidence: ~0.4–0.9% of pregnancies; increasing with caesarean rates.

- Risk factors: prior uterine surgery (caesarean, myomectomy), multiparity, placenta previa.

Classification

- Accreta: villi adhere to myometrium.

- Increta: invasion into myometrium.

- Percreta: penetration through uterine serosa ± adjacent organs.

Anaesthetic Considerations

- Planned delivery at 34–36 weeks in a centre of excellence with interventional radiology on standby.

- Neuraxial anaesthesia may be feasible if minimal anticipated blood loss.

- General anaesthesia with invasive arterial and central venous monitoring when massive haemorrhage is anticipated

- Adjuncts (balloon occlusion, cell salvage)

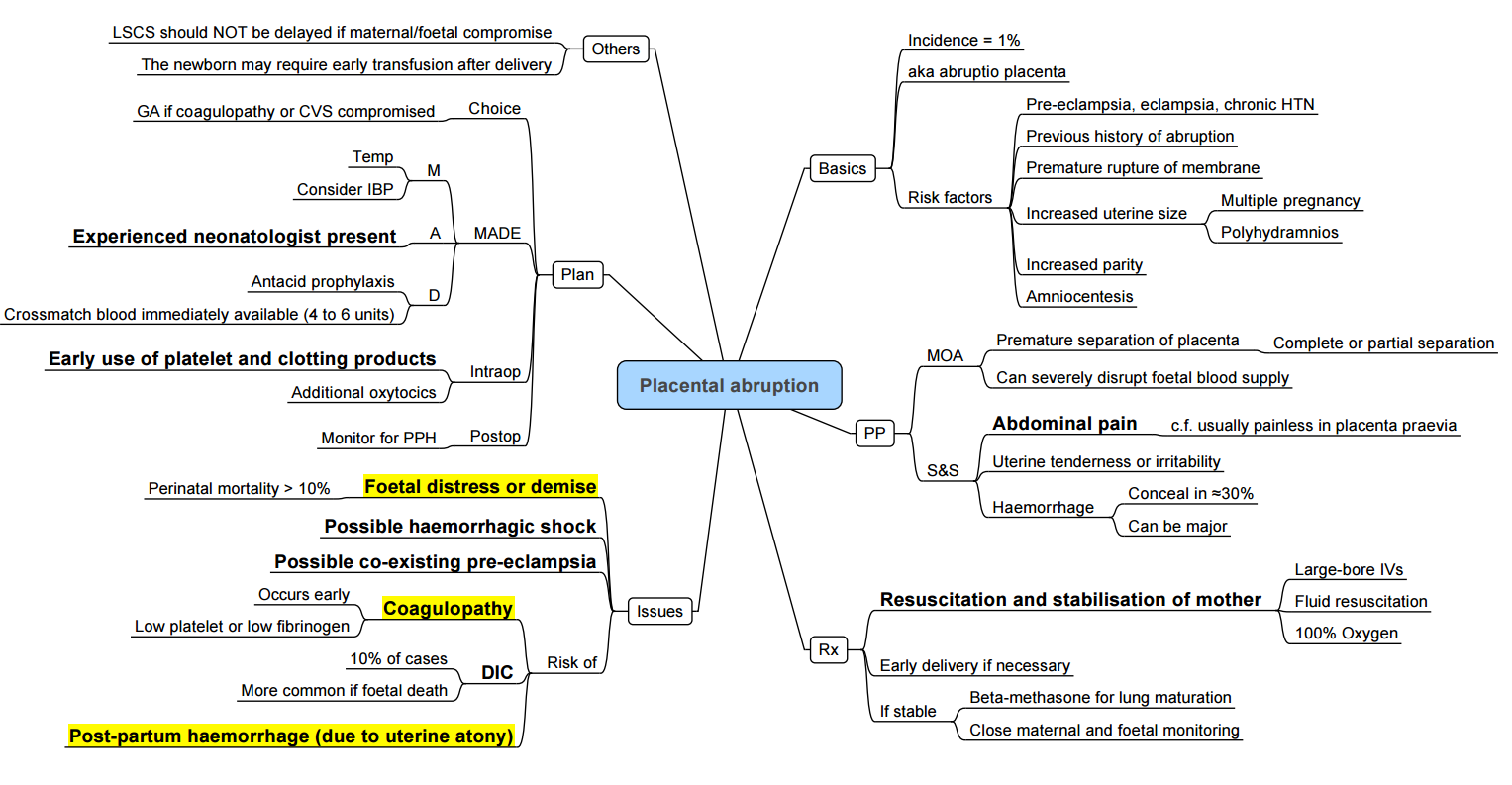

Placental Abruption

Incidence and Risk Factors

- Occurs in 0.6–1.2% of pregnancies.

- Risk factors: hypertension, trauma, pre-eclampsia, smoking, cocaine use, multiparity, short umbilical cord.

Clinical Presentation and Severity

- Vaginal bleeding ± uterine tenderness; may be concealed.

- Graded I–III (mild to severe) by volume of bleeding, uterine tone, maternal/fetal compromise

Management

- Immediate haemodynamic stabilisation and coagulation support.

- Emergency caesarean under general anaesthesia with rapid-sequence induction if maternal or fetal distress.

- Utilise massive transfusion protocols and point-of-care coagulation testing.

Uterine Rupture

Risk Factors and Presentation

- Risk factors: scarred uterus (prior caesarean/myomectomy), obstructed labour, oxytocin-induced hypertonus.

- Presentation: sudden abdominal pain, loss of fetal station, bleeding, shock.

Management

- Emergency laparotomy and delivery under general anaesthesia.

- Be prepared for hysterectomy and massive blood replacement.

Post Partum Haemorrhage

Definition

- Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists as cumulative blood loss ≥ 1000 mL or any blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolaemia within 24 hours of delivery, irrespective of mode of birth

- Severe PPH: blood loss > 2000 mL and/or transfusion of ≥ 4 packed red blood cells (PRBCs).

- Timing:

- Primary (early): within 24 hours of delivery

- Secondary (late): > 24 hours and up to 12 weeks postpartum

Pathogenesis (the “Four T’s”)

- Tissue

- Retained placental fragments prevent adequate myometrial contraction and vessel compression.

- Risk factors: manual removal of placenta, placenta accreta spectrum, uterine atony.

- Thrombin (coagulopathy)

- Consumptive coagulopathy (e.g. disseminated intravascular coagulation), pre‐existing bleeding disorders.

- Obstetric triggers: placental abruption, amniotic fluid embolism, pre‐eclampsia.

- Tone (uterine atony)

- Most common cause (≈ 70% of PPH).

- Predisposing factors: over-distension (multiple gestation, polyhydramnios, macrosomia), prolonged or augmented labour (oxytocin), general anaesthesia.

- Trauma

- Genital tract lacerations, uterine rupture, instrumental delivery, caesarean section.

- Additional risk factors include maternal age > 34 years, multiparity, fibroids, smoking, chorioamnionitis, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Clinical Recognition

- Visual estimation of blood loss underestimates actual loss by up to 50%.

- Rule of 30 (≈ 30% of maternal blood volume lost):

- Haemoglobin ↓ 30%

- Urine output < 30 mL/h

- Heart rate ↑ 30 bpm

- Systolic blood pressure ↓ 30 mmHg

- Respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min

- Shock index (heart rate ÷ systolic blood pressure)

- Normal ≤ 0.9; > 1.7 predicts need for ≥ 4 units PRBCs, hysterectomy, ICU admission, mortality

Management Algorithm

Step 1: Recognition and Initial Resuscitation (≤ 30 min)

- Call for help: obstetric, anaesthetic and haematology teams.

- Monitoring: blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation, urine output, shock index.

- Establish two large-bore IV lines; send for full blood count, coagulation screen, group and cross-match.

- Send fixed-ratio red cell and plasma packs via massive transfusion protocol (MTP).

- Uterine massage and manual removal of retained tissue if indicated.

Step 2: Uterotonic Agents

- Administer sequentially if tone remains inadequate:

- Oxytocin: 10–30 IU in 1 L crystalloid infusion (slow infusion; bolus avoided).

- Ergometrine (methylergometrine) 0.2 mg IM (contraindicated if hypertension).

- Carboprost (15-methyl prostaglandin F₂α) 250 µg IM every 15–30 min up to 2 mg total (contraindicated in asthma).

- Misoprostol 800 µg rectally or sublingually.

Step 3: Haemostatic Support and Monitoring (next 30 min)

- Point-of-care coagulation testing (TEG/ROTEM) to guide component therapy:

- Maintain fibrinogen ≥ 4 g/L (normal in term pregnancy 4.5–6 g/L).

- Platelets ≥ 75 × 10⁹/L; PT/INR < 1.5 × normal; aPTT < 1.5 × normal.

- Tranexamic acid 1 g IV over 10 min; may repeat once.

- Fibrinogen concentrate or cryoprecipitate to restore fibrinogen.

- Consider recombinant factor VIIa only after correction of acidosis, hypothermia, thrombocytopenia and hypofibrinogenaemia.

Step 4: Mechanical and Surgical Interventions

- Mechanical tamponade: intrauterine balloon (e.g. Bakri).

- Compression sutures: B-Lynch or modified sutures.

- Arterial ligation: uterine or internal iliac arteries.

- Hysterectomy for life-threatening haemorrhage unresponsive to conservative measures.

- Consider interventional radiology (embolisation) if stable and available.

Massive Transfusion Protocol

- Initial pack: 6 units O RhD-negative red cells, 4 units AB plasma, 1 apheresis platelet unit.

- Ratio-based vs goal-directed: current evidence favours point-of-care–guided therapy to minimise volume overload and TRALI.

Blood Conservation Strategies

- Antepartum: screen and treat iron-deficiency anaemia (target Hb ≥ 11 g/dL).

- Postpartum: consider IV iron before transfusion if stable.

- Cell salvage: safe in high-risk caesarean sections with leukocyte filtration and appropriate Rho(D) immunoglobulin.

Cyklokapron (Tranexamic Acid) in Obstetric Cesarean Section – Evidence Summary

| Category | Details / Evidence |

|---|---|

| Primary Use | Prophylactic TXA (Cyklokapron) at 1 g IV before skin incision, alongside uterotonic therapy in cesarean delivery. |

| Effect on Blood Loss | Meta-analysis of ~50 RCTs showed reduced risk of blood loss > 1000 mL, lower mean blood loss, reduced transfusion needs, and less drop in hemoglobin, with greater benefit in high‑risk patients. |

| Timing of Administration | Benefit seen when TXA given before skin incision; no clear benefit if administered after cord clamping. |

| Maternal Mortality / Clinical Endpoints | Large trials (e.g. TRAAP‑2, NIH-MFM Units Network) confirmed reduced blood loss but no significant reduction in mortality or composite need-for-transfusion endpoints. |

| Safety & Thrombotic Risk | No significant increase in thromboembolic events overall; incidence remains low and statistically nonsignificant. Minor GI side effects may be modestly increased. |

| Evidence Quality | Moderate quality for high‑risk populations; overall evidence for low-risk populations rated low to very low. |

| Guideline Status | WHO and obstetric panels continue to support IV TXA for treatment of PPH. Prophylactic use in Cesarean section remains conditionally recommended, especially in high‑risk scenarios. |

| Outstanding Research | Ongoing trials (e.g. TRAAP‑VIA, I’M WOMAN) focusing on placenta previa, anaemic populations, and alternative TXA routes; results expected by late 2025. |

Practice Conclusion

- Use of prophylactic IV TXA before incision in Cesarean delivery reduces hemorrhage and transfusion needs, with greater benefit in high-risk patients.

- The effect on clinical mortality or composite transfusion endpoints remains unproven.

- Thromboembolic risk is not significantly elevated under current dosing and use patterns.

- Optimal dosing, high-risk subgroup targeting, and administration timing continue to be refined in ongoing trials.

Links

- Polytrauma and haemorrhagic shock

- Point of Care Coagulation testing

- Clotting cascade

- Resus end targets in shock

- Obstetric emergencies

- Blood conservation in cardiac surgery

- Blood transfusions and conservation strategies

- Hypertension in pregnancy

References:

- Velde, M. V. d. and Varon, A. J. (2015). Obstetric hemorrhage. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 28(2), 186-190. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000000168

- Van de Velde, Marca; Diez, Christianb; Varon, Albert J.b. Obstetric hemorrhage. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 28(2):p 186-190, April 2015. | DOI: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000168

- Butwick, Alexander J.a; Goodnough, Lawrence T.b,c. Transfusion and coagulation management in major obstetric hemorrhage. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 28(3):p 275-284, June 2015. | DOI: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000180

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- PPH Image: Novice Anaesthesia. (2021). Infographics. Retrieved April 24, 2025, from https://www.gasnovice.com/infographics

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. Green-top Guideline No. 52. London: RCOG; 2017.

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: WHO; 2019.

- Roberts I, Shakur H, Afenyi-Annan A, et al. The WOMAN Trial: tranexamic acid for the treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2105–16.

- Collins PW, et al. Early fibrinogen concentrate replacement in postpartum haemorrhage: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2016;116(6):804–12.

- Sentilhes L, Kayem G, Perrotin F, et al. Conservative management of severe postpartum haemorrhage using intrauterine balloon tamponade. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(4):613–19.

Summaries

Obs_Haemorrhage

—

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “dc9a2130-ce3c-4e2a-b8ef-5ab01bac8872”