- Anatomy and Physiology of the Pericardium

- Pathology of the Pericardium

- Pericardial Effusion & Tamponade

- Constrictive Pericarditis

- Anaesthesia for Pericardiectomy

- Links

- Past Exam Questions

{}

Anatomy and Physiology of the Pericardium

- Composition:

- Layers:

- Inner Visceral Layer: Thin, adherent to, and continuous with the epicardium of the heart.

- Outer Parietal Layer: Thicker and more fibrous.

- Thickness:

- Normal pericardial thickness: 1–2 mm.

- Layers:

- Pericardial Fluid:

- Volume: Normal = 15–50 ml.

- Production: By visceral mesothelial cells.

- Drainage: Via the lymphatic system into the right side of the heart.

- Function:

- Minimizes friction on the epicardium during heart movements.

- Balances hydrostatic pressures over the heart surface.

- Pericardial Sinuses:

- Oblique Sinus: Located posteriorly between the left atrium and pulmonary veins.

- Transverse Sinus: Located behind the left atrium, behind the aorta, and pulmonary artery.

- Physiological Benefits:

- Stabilizes the heart in its anatomical position.

- Limits excessive movement within the chest cavity.

- Prevents acute distention of cardiac chambers.

- Optimizes atrial and ventricular coupling and filling.

- Acts as a barrier against the spread of infection or neoplasm.

- Secretes prostaglandins that regulate autonomic cardiac reflexes, myocardial contractile function, and coronary artery tone.

Pathology of the Pericardium

Congenital Defects

- Associations:

- Often associated with other cardiac, pulmonary, and skeletal abnormalities.

- Incidence: 1 in 10,000 (usually found at autopsy).

- Types:

- Partial Absence:

- More common on the left side (70%) than the right side (17%).

- Left-sided Defects: Predispose to herniation of the heart, which can become hemodynamically significant during anesthesia induction or cause prolonged ischemia.

- Right-sided Defects: May cause significant compression of the vena cava.

- Total Absence:

- Rare.

- Excessive cardiac motion and displacement increase the risk of traumatic aortic dissection.

- Partial Absence:

Acute Pericarditis

Etiology

- Infectious:

- Viral (Coxsackie B), bacterial, mycobacterial (tuberculosis).

- Non-infectious:

- Post-cardiac surgery, trauma, malignancy, acute myocardial infarction, post-acute MI (Dressler’s syndrome), uremia (renal failure), or post-radiation.

- Auto-immune:

- Rheumatic fever, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or drug-induced (procainamide, dantrolene, heparin, warfarin).

Symptoms

- Sharp left precordial or retrosternal chest pain, pleuritic in nature, varying with posture (decreased on sitting, increased on lying supine), may radiate to the trapezius ridge.

- Prodromal symptoms of malaise, fever, and generalized myalgia.

- Tachycardia and tachypnea are usually out of proportion to the low-grade fever.

- Triphasic friction rub (atrial systole, ventricular systole, and early diastole).

Differentials

- Acute coronary syndrome, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism.

Complications

- May develop pericardial effusion and/or tamponade.

Risk Factors for Complications

- Bacterial or fungal infections, malignancies, end-stage renal disease, post-cardiac surgery.

Special Investigations

- ECG: Sinus tachycardia, PR depression, diffuse concave upward ST-segment elevation.

- ECHO: May show effusion and tamponade if present, other cardiac or para-cardiac disease.

Treatment

- Symptomatic:

- NSAIDs, colchicine to prevent recurrence.

- Low-dose corticosteroids if associated with autoimmune disease.

Chronic Pericarditis

- Management depends on hemodynamic influence.

- Differentiate between chronic pericarditis, relapsing disease, and chronic pericardial effusion.

- Symptomatic treatment with NSAIDs, colchicine, and corticosteroids before elective surgery.

- Pericardiectomy is indicated for severe, unresponsive symptoms.

- Moderate to large effusions (>10 mm separation during diastole) should be drained before elective surgery.

Pericardial Effusion & Tamponade

Etiology

- Systemic Inflammatory Disease: SLE, RA.

- Infection: Bacterial, viral, fungal.

- LV/RV Free Wall Rupture; Aortic Dissection.

- Drugs/Toxins/Uremia/Radiation.

- Post-Myocardial Infarction.

- Trauma.

- Malignancy.

- Congestive Heart Failure; Pulmonary Hypertension; Cirrhosis:

- ↑ Capillary hydrostatic pressure; fluid transudate (serous).

- Nephrotic Syndrome (rare):

- Usually exudative secondary to inflammation.

Pericardial Effusion

- Fluid Accumulation:

- Gradual accumulation is better tolerated.

- Rapid accumulation of low volumes or slow accumulation of high volumes.

- Symptoms:

- Asymptomatic.

- Sharp pain (↑ while supine/with inspiration).

- Dull chest pain.

- Dysphagia, dyspnea, hoarse voice (if size compresses esophagus, lungs, or recurrent laryngeal nerve).

- Signs:

- Elevated intra-cardiac pressures on cardiac catheterization.

- ↓ ECG Voltages.

- Soft S1/S2.

- Cardiomegaly on chest X-ray.

- Hypo-echoic area surrounding chambers on Echo.

- ↑ JVP/Pedal Edema/Liver Size.

- Hypotension.

- Dyspnea/Crackles on respiratory auscultation.

- Beck’s Triad for Tamponade:

- Hypotension.

- Jugular Venous Distension.

- Muffled heart sounds.

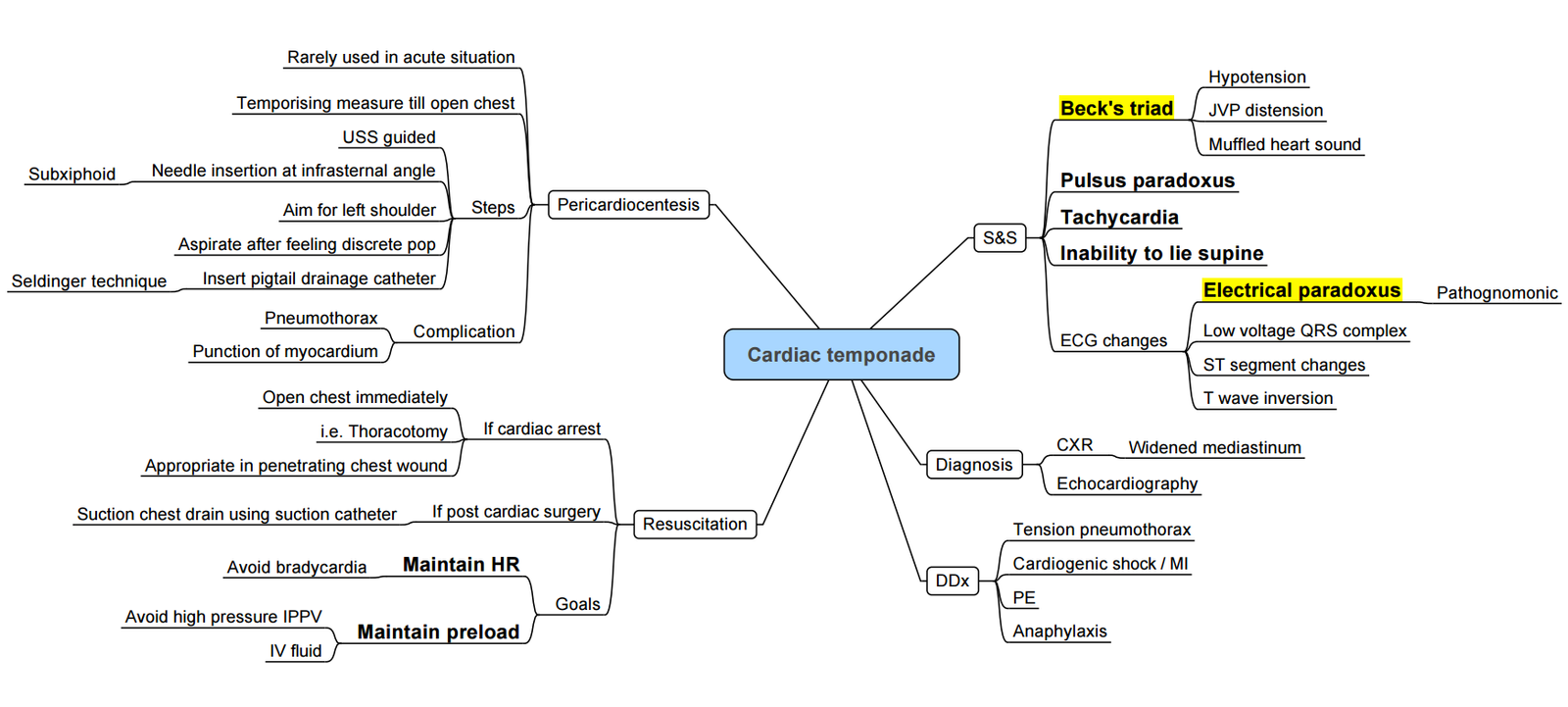

Cardiac Tamponade

Overview

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition characterized by the accumulation of fluid in the pericardial space, leading to increased intrapericardial pressure, impaired cardiac filling, and reduced cardiac output.

Pathophysiology

-

Mechanism:

- Accumulation of pericardial fluid increases intrapericardial pressure.

- Compression of cardiac chambers, especially right-sided structures, during diastole.

- Fixed ventricular volume with inspiratory septal shift toward the LV → ↓ LV filling.

- Transmural pressure gradient (intrapericardial − intracardiac) compromises chamber filling.

- Diastolic dysfunction and unimodal venous return pattern in severe tamponade.

- If untreated, leads to obstructive shock and death.

-

Hemodynamic Effects:

- Rapid Accumulation

- Exceeds pericardial compliance quickly.

- Steep rise in pericardial pressure → acute tamponade.

- Slow Accumulation:

- Pericardium stretches, delaying symptom onset.

- Gradual pressure increase allows compensation.

- Rapid Accumulation

Hemodynamic Consequences

-

Pressure Effects:

- Right atrial pressure increases first (lowest chamber pressure).

- ↓ Venous return as RA pressure > systemic venous pressure.

- ↓ RV stroke volume → ↓ pulmonary flow → ↓ LV filling.

- Leads to equalization of left-sided pressures, ↓ cardiac output, and potential for PEA.

-

Effect of Positive Pressure Ventilation (PPV):

- ↑ Intrathoracic pressure → ↓ venous return.

- ↑ RV afterload and LV preload.

- May worsen tamponade physiology in some patients.

Aetiology

- Common Causes:

- Idiopathic, iatrogenic (post-cardiac surgery/intervention, pacemaker insertion), trauma, malignancy, end-stage renal disease, autoimmune, infection (e.g. TB), aortic dissection, radiation

- Effusion Types:

- Transudative, exudative, hemorrhagic, purulent.

- Pericardial Fluid Volume:

- Normal: 15–50 mL.

- ESRD-Specific Considerations:

- Uremic pericarditis improves with dialysis.

- Dialysis-associated pericarditis often requires drainage.

- Chronic disease and hypertension may blunt tamponade physiology.

Clinical Presentation

-

Symptoms:

- Dyspnea, orthopnea, chest pain, diaphoresis, tachycardia

-

Signs:

-

Beck’s Triad:

- Hypotension, elevated JVP, muffled heart sounds.

-

Pulsus Paradoxus:

- More than 10 mmHg drop in systolic BP on inspiration.

- Due to increased RV filling and septal shift reducing LV output.

- Not specific; seen in asthma, COPD, obesity, etc.

-

Diagnostic Features

- Echocardiography:

- Gold standard; assesses effusion size and chamber collapse.

- Effusion Grading:

- Small <10mm, Moderate 10–20 mm, Large >20 mm.

- RA collapse >30% of cardiac cycle suggests tamponade.

- IVC dilation → elevated RA pressure.

- Respiratory variation in mitral/tricuspid inflow and septal shift.

- ECG:

- Sinus tachycardia, low voltage QRS/T, PR depression, electrical alternans, nonspecific ST-T changes.

- Chest X-ray:

- Enlarged cardiac silhouette, widened mediastinum, right costo-phrenic angle blunting, possible pleural effusion.

Pulsed Wave Doppler Tracing in Cardiac Tamponade

- Technique: Pulsed wave Doppler tracing using a mid-oesophageal 4-chamber view on trans-oesophageal echocardiography (TEE).

- Purpose: To view trans-mitral flow velocities in a spontaneously breathing patient with tamponade.

- Finding: Reduction in velocities during inspiration, highlighting pulsus paradoxus.

Cardiac Catheterization in Cardiac Tamponade

Overview:

- Cardiac catheterization is generally not performed as a diagnostic tool for tamponade because echocardiography is less invasive and provides sufficient diagnostic information.

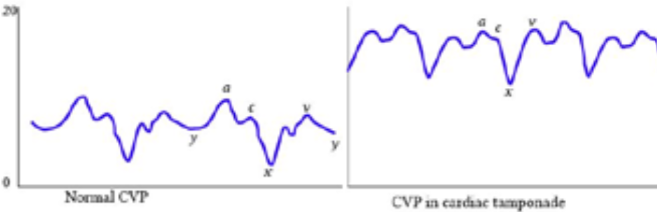

Central Venous Pressure (CVP) Tracing

- V Wave: Represents venous filling of the right atrium.

- Y Descent: Indicates the drop in right atrial pressure as the tricuspid valve opens and blood flows into the right ventricle.

- Blunted Y Descent in Tamponade:

- Due to the increased intrapericardial pressure, which quickly equalizes with the right atrial pressure, limiting the effective filling of the RV.

- Results in a less pronounced drop in pressure (blunted descent) on the CVP tracing

Clinical Significance

- Blunted Y Descent: Suggestive of cardiac tamponade, indicating impaired ventricular filling.

- Echocardiography: Preferred for diagnosing cardiac tamponade due to its non-invasive nature and detailed visualization of cardiac structures and hemodynamics.

Management

Drainage

-

Needle Pericardiocentesis:

- Seldinger technique under imaging guidance.

- Performed under local anesthesia.

- Diagnostic and therapeutic; risk of complications.

-

Surgical Approaches:

- Subxiphoid Pericardiostomy: Simple, local anesthesia.

- Pericardial Window: For ongoing drainage.

- Sternotomy/Thoracotomy: For severe cases or when tamponade recurs; may need cardiopulmonary bypass.

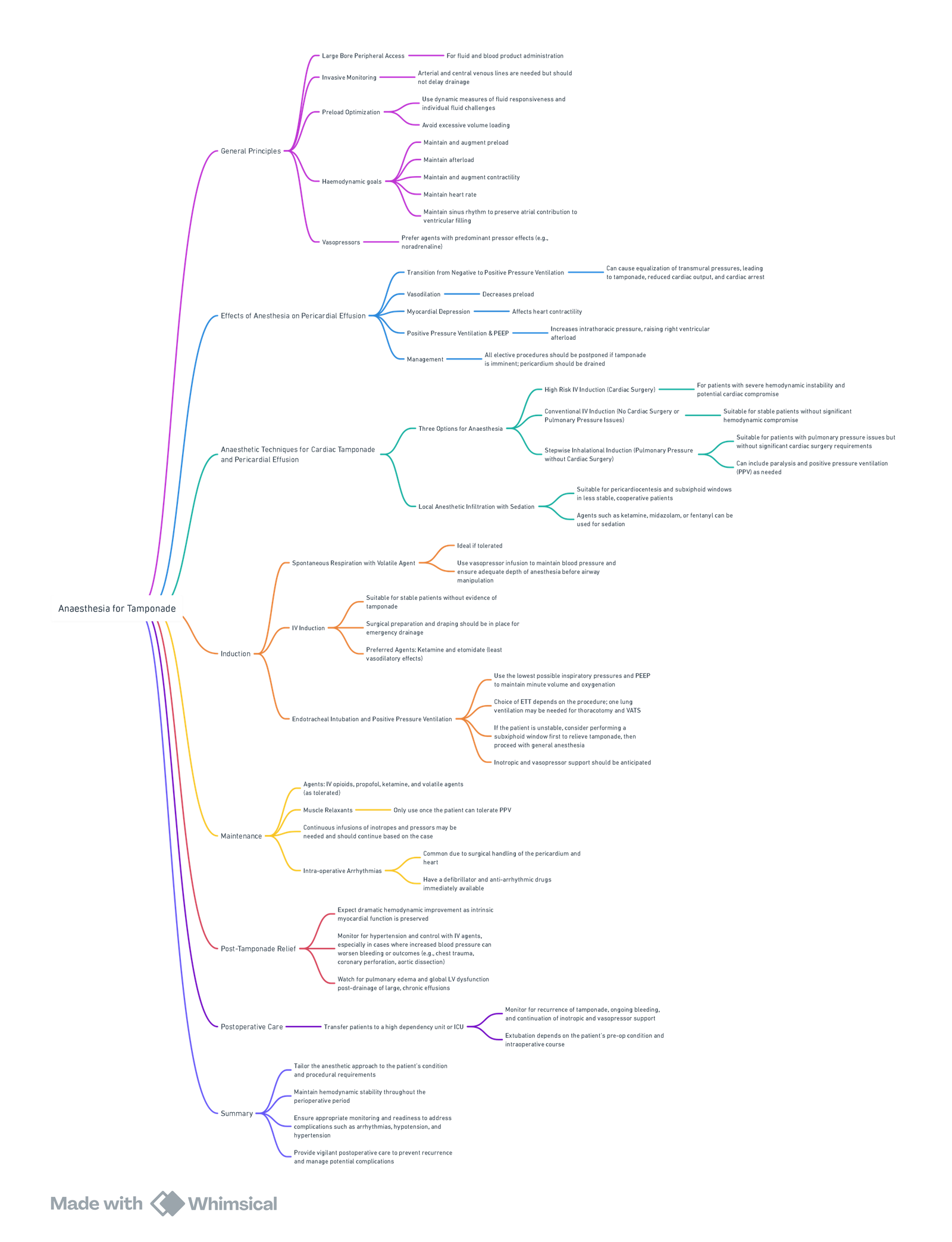

Anaesthesia For Pericardial Tamponade

General Principles

- Large-Bore Peripheral Access:

- Required for rapid fluid and blood product administration.

- Invasive Monitoring:

- Arterial and central venous lines are useful but should not delay pericardial drainage.

- Use dynamic measures for fluid responsiveness and guide individual fluid challenges.

- Preload Optimization:

- Avoid excessive volume loading.

- Maintain and augment preload.

- Haemodynamic Goals:

- Maintain and augment afterload and contractility.

- Maintain heart rate and sinus rhythm to preserve atrial contribution to ventricular filling.

- Vasopressors:

- Prefer agents with predominantly pressor effects (e.g., noradrenaline).

Effects Of Anaesthesia on Pericardial Effusion

- Transition from Negative to Positive Pressure Ventilation:

- Can lead to equalization of transmural pressures, potentially causing tamponade, reduced cardiac output, or cardiac arrest.

- Vasodilation:

- Reduces preload.

- Myocardial Depression:

- Negatively affects cardiac contractility.

- Positive Pressure Ventilation & PEEP:

- Increases intrathoracic pressure, raising right ventricular afterload.

- Management:

- Elective procedures should be postponed if tamponade is imminent; the pericardium should be drained first.

Anaesthetic Techniques for Cardiac Tamponade and Pericardial Effusion

- Three Options for Anaesthesia:

- High-Risk IV Induction (Cardiac Surgery): For severe hemodynamic instability and potential cardiac compromise.

- Conventional IV Induction (No Cardiac Surgery or Pulmonary Pressure Issues): Suitable for stable patients without significant hemodynamic compromise.

- Stepwise Inhalational Induction (Pulmonary Pressure without Cardiac Surgery): Suitable for patients with pulmonary pressure issues but no significant cardiac surgery needs; allows paralysis and positive pressure ventilation (PPV) as required.

- Local Anaesthetic Infiltration with Sedation:

- Appropriate for pericardiocentesis and subxiphoid windows in cooperative patients.

- Agents like ketamine, midazolam, or fentanyl are preferred.

Induction

- Spontaneous Respiration with Volatile Agent:

- Ideal if tolerated.

- Use vasopressor infusions to maintain blood pressure and ensure adequate depth of anaesthesia before airway manipulation.

- IV Induction:

- Suitable for stable patients without evidence of tamponade.

- Preferred agents: Ketamine and etomidate (minimal vasodilatory effects).

- Surgical preparation should be in place for emergency drainage.

- Endotracheal Intubation and Positive Pressure Ventilation:

- Use the lowest inspiratory pressures and PEEP to maintain minute ventilation and oxygenation.

- Choice of endotracheal tube (ETT) depends on the procedure; one-lung ventilation may be needed for thoracotomy and VATS.

- For unstable patients, consider subxiphoid window first to relieve tamponade, then proceed with general anaesthesia.

- Inotropic and vasopressor support should be anticipated.

Maintenance

- Agents:

- IV opioids, propofol, ketamine, and volatile agents (as tolerated).

- Muscle Relaxants:

- Use only once the patient can tolerate PPV.

- Inotropes and Vasopressors:

- Continuous infusions may be needed based on haemodynamic requirements.

- Intraoperative Arrhythmias:

- Common due to surgical handling of the pericardium and heart.

- A defibrillator and anti-arrhythmic drugs should be readily available.

Post-Tamponade Relief

- Expect significant haemodynamic improvement if intrinsic myocardial function is preserved.

- Monitor for hypertension and control with IV agents, as excessive blood pressure may exacerbate bleeding or trauma (e.g., chest trauma, coronary perforation, aortic dissection).

- Watch for pulmonary edema and global left ventricular dysfunction after drainage of large or chronic effusions.

Postoperative Care

- Transfer patients to a high dependency unit (HDU) or ICU.

- Monitor for:

- Recurrence of tamponade.

- Ongoing bleeding.

- Continuation of inotropic and vasopressor support.

- Extubation:

- Depends on preoperative condition and intraoperative course.

Summary

- Tailor anaesthetic management to the patient’s condition and procedural requirements.

- Maintain haemodynamic stability throughout the perioperative period.

- Ensure appropriate monitoring and readiness to manage complications such as arrhythmias, hypotension, or hypertension.

- Provide vigilant postoperative care to prevent recurrence and manage potential complications.

What’s New

- Expanded insight into the pathophysiology of tamponade:

- Emphasis on the rate of fluid accumulation as more critical than volume alone for tamponade onset.

- Slow accumulation allows adaptive mechanisms; acute tamponade can result from as little as 50 mL.

- Added concept of diastolic suction and detailed phases of diastolic filling.

- Updated guidance on anaesthetic management:

- Use of “full, fast, strong” strategy for tamponade: preload optimisation, tachycardia preservation, and inotropy.

- Stronger emphasis on avoiding bradycardia, vasodilation, and positive pressure ventilation (PPV) in unstable patients.

- Avoidance of premedication and prioritisation of awake pericardiocentesis under local anaesthetic for cooperative patients.

- Pre-induction preload augmentation is now standard for tamponade patients.

- TEE and focused transthoracic ultrasound now recommended routinely perioperatively.

- Enhanced discussion of cardiac surgery-related tamponade:

- Risk of loculated hematomas post-op even with open pericardium.

- Late tamponade (>7 days post-op) has higher mortality and is often related to anticoagulation or pacing wire removal

- Clinical sign updates:

- Beck’s triad sensitivity is low (50%).

- Pulsus paradoxus remains important but non-specific; influenced by respiratory mechanics.

- Investigative and Imaging Enhancements:

- Increased reliance on bedside point-of-care echocardiography (FOCUS).

- Preference for multiplanar imaging to detect loculated effusions.

Practical Implications

- Ensure readiness for rapid drainage and resuscitation in unstable patients.

- Incorporate echocardiography pre-induction, especially if patient is borderline stable.

- Prioritise local anaesthesia approaches where feasible for effusion drainage.

- Avoid induction in high-risk tamponade unless immediate drainage can be performed.

- Pericardial window should be considered if reaccumulation risk or loculated effusion.

Constrictive Pericarditis

- Definition

- Chronic inflammation of the pericardium causes it to thicken, become non-compliant, and rigid, restricting cardiac chamber expansion during diastole, leading to impaired cardiac filling and diastolic dysfunction.

- Causes:

- Idiopathic, infectious, post-cardiac surgery, following radiation to the mediastinum, trauma, or autoimmune diseases.

Pathophysiology

- Normal Pericardium: Accommodates changes in cardiac volume.

- Thickened, Calcified Pericardium:

- Limits cardiac chamber expansion.

- Early diastolic filling is initially unaffected.

- Atrial contribution to ventricular filling is mostly impeded during mid to late diastole.

- Leads to a fixed stroke volume state, requiring an increased heart rate to meet tissue perfusion demands.

- Intrathoracic Pressure Changes:

- Not transmitted to the heart, leading to the absence of normal inspiratory augmentation of venous return to the right heart.

- Results in an inspiratory increase in CVP (Kussmaul’s sign).

- Respiratory Variation:

- Pulmonary veins lie outside the pericardium; changes in intrathoracic pressures affect pulmonary vein flow.

- Negative pressure ventilation reduces LV filling and systolic blood pressure but does not typically cause pulsus paradoxus.

- Ventricular Interdependence:

- Pressure changes in one ventricle are transferred to the other, leading to equilibration of diastolic pressures.

- Small septal shifts have minimal effect on filling due to high baseline diastolic pressures.

- Myocardial Atrophy:

- Chronic constriction can cause myocardial atrophy, leading to continued diastolic and significant systolic dysfunction, even after pericardiectomy.

Clinical Signs and Diagnosis

- Symptoms:

- Similar to right ventricular failure: Tachycardia, fluid overload, decreased cardiac output, shortness of breath, and fatigue.

- Ascites, hepatomegaly, pleural effusion, peripheral edema, cachexia.

- Pericardial Knock: High-pitched sound in early diastole.

- Kussmaul’s Sign: Increase in jugular venous pressure on inspiration.

- Differential Diagnosis:

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolus, right ventricular infarction, pleural effusion, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Special Investigations

- Chest X-ray:

- Ring of calcification around the heart, possible cardiomegaly if associated with effusion.

- ECG:

- Low voltages, non-specific ST-T changes, atrial fibrillation, P mitrale.

- CT Scan and MRI:

- Confirm pericardial thickening and calcification.

- Echocardiography:

- Increased pericardial thickness (>2mm), inspiratory posterior motion of the septum in diastole, nonpulsatile dilated IVC.

- Pulsed Wave Doppler (PWD): Specific trans-mitral flow velocity pattern.

- Cardiac Catheterization:

- RV Trace: Square root sign, rapid drop in RV pressure in early diastole (“dip”) followed by a plateau.

Differentiating Constrictive Pericarditis (CP) from Restrictive Cardiomyopathy (RC)

- CP:

- Uncoupling of intrathoracic and intracardiac pressures.

- Increased ventricular interdependence.

- Normal E wave velocities on ECHO indicating preserved elastic recoil and compliance of the LV.

- Respiratory variation in pulmonary vein flow.

- RC:

- Intrinsic myocardial disease with impaired relaxation and reduced compliance.

- Reduced E wave velocities due to impaired myocardial function.

- No respiratory variation in pulmonary vein flow.

Clinical Features Differentiating Constrictive Pericarditis from Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

| Clinical Feature | Constrictive Pericarditis | Restrictive Cardiomyopathy |

|---|---|---|

| Early diastolic sound | Frequent | Occasional |

| Late diastolic sound | Rare | Frequent |

| Atrial enlargement | Mild or absent | Marked |

| Atrioventricular or intraventricular conduction defect | Rare | Frequent |

| QRS Voltage | Normal or low | Normal or high |

| Pulsus paradoxus | Frequent, but usually mild | Rare |

| Pericardium | Thickened | Normal |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | Unusual | Frequent |

| Mitral or Tricuspid regurgitation | Rare | Frequent |

| Transmitral E wave velocity | Normal (or elevated) | Reduced |

| Transmitral flow velocity variation | Common: exhalation > inspiration (≥ 25%) | Rare |

| Pulmonary venous flow velocities | Respiratory variation (≥ 25%); S:D > 1 | Little respiratory variation; S:D < 1 |

| Mitral annular velocities | E’ ≥ 8 cm sec⁻¹ | E’ < 8 cm sec⁻¹ |

| CVP | No respiratory variation | Normal respiratory variation |

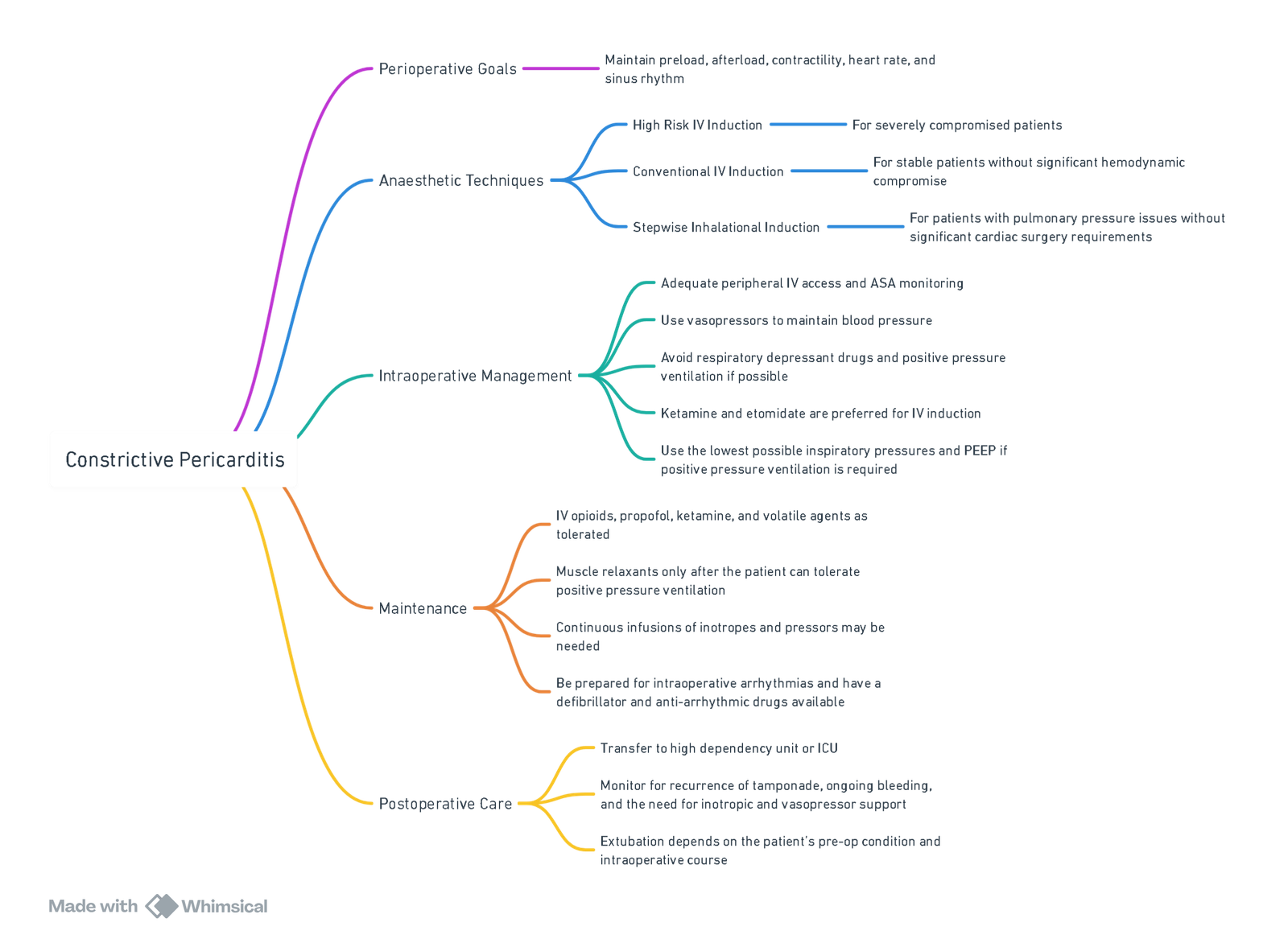

Management of Constrictive Pericarditis

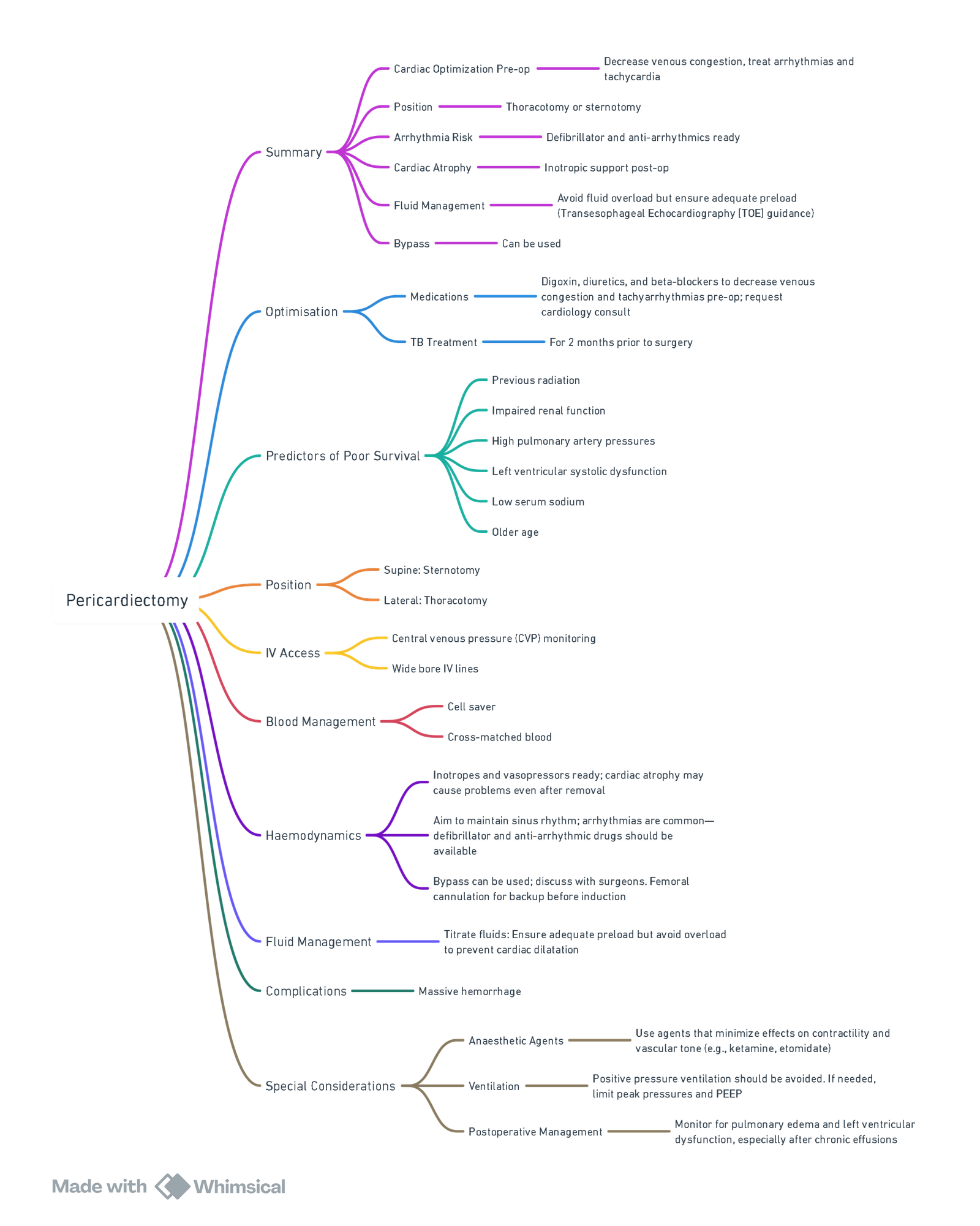

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Anaesthesia for Pericardiectomy

Overview

Pericardiectomy with complete decortication is the definitive treatment for established constrictive pericarditis. The perioperative management is complex and requires meticulous planning and monitoring due to the significant risks involved.

Surgical Approach

- Pericardial stripping is typically performed via sternotomy or lateral thoracotomy.

- Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) support may be used depending on the patient’s preoperative condition and intraoperative complications.

Mortality and Risks

- Perioperative mortality is highly dependent on the preoperative New York Heart Association (NYHA) status.

- The operation carries significant risks, including:

- Massive hemorrhage.

- Damage to the epicardium, myocardium, and coronary vessels.

- Persistent constrictive physiology and abnormal diastolic filling patterns postoperatively.

- Overall mortality is around 12%.

Pre-operative Assessment

Signs & Symptoms

- Tachycardia (fixed stroke volume state)

- Fluid overload (peripheral edema → anasarca) leading to pleural effusions, ascites, hepatomegaly

- Decreased cardiac output (CO), shortness of breath (SOB), fatigue

- Pericardial knock

- Cachexia

- Kussmaul’s sign (increased jugular venous pressure [JVP] on inspiration)

Special Investigations

- Chest X-ray (CXR): Calcification ring around the heart ± cardiomegaly

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): p-mitrale, upsloping ST-T waves, atrial fibrillation (AF), low voltages

- Computed Tomography (CT) / Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Confirm myocardial thickening and calcification

- Echocardiography (ECHO): Increased E/A ratio, decreased pulmonary vein flow due to increased left atrial pressures

- Cardiac Catheterization: Square root sign (rapid filling and rapid drop-off)

Anaesthetic Issues in Managing Constrictive Pericarditis for Pericardiectomy

1. Optimizing Medical Management

- Medications:

- Diuretics, digoxin, β-blockers

- Anti-tuberculosis (TB) treatment for at least 2 months before surgery

2. Haemodynamic Goals

- Contractility: Maintain and augment

- Rate: Maintain normal sinus rhythm (NSR) to preserve atrial contribution to ventricular filling

- Afterload: Maintain

- Preload: Maintain or augment, but avoid overload

3. Anticipate

- Arrhythmias

- Massive Hemorrhage:

- Massive transfusion protocol (MTP)

- Whole blood intravenous (WBIV)

- Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) support

- Inotropes/pressors ready and running

- Persistent Constrictive Physiology:

- May require inotropes and congestive heart failure (CCF) management even after release due to chronic changes

Conduct of Anaesthesia for Pericardiectomy

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Links

Past Exam Questions

Post-CABG Hypotension in an Elderly ICU Patient

You are asked to review an elderly severely hypotensive patient in ICU, 3 hours after a CABG procedure. The patient has raised JVP and very soft heart sounds on auscultation.

a) What is the most likely diagnosis? (1)

b) List 6 additional clinical features on examination that will support your diagnosis. (3)

c) What 3 urgent investigations will confirm your diagnosis and how? (6)

References:

- Up-to-date. Anesthesia for patients with pericardial disease and/or cardiac tamponade. Literature review current through April 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/anesthesia-for-patients-with-pericardial-disease-and-or-cardiac-tamponade

- Madhivathanan P, Corredor C, Smith A. Perioperative implications of pericardial effusions and cardiac tamponade. BJA Education. 2020;20(7):226-234. doi:10.1016/j.bjae.2020.03.006

- Correia M. Anaesthesia for patients with pericardial disease. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2018;24(3)(Supplement 1):S67-S78.

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- ICU One Pager. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://onepagericu.com/

- Correia M. Anaesthesia for Patients with Pericardial Disease [Internet]. Inflammatory Heart Diseases. IntechOpen; 2019. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82540

Summaries:

Considerations

Anaesthesia for pericardectomy-video

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “dfccd079-ba1e-48bf-b353-51887ced321b”