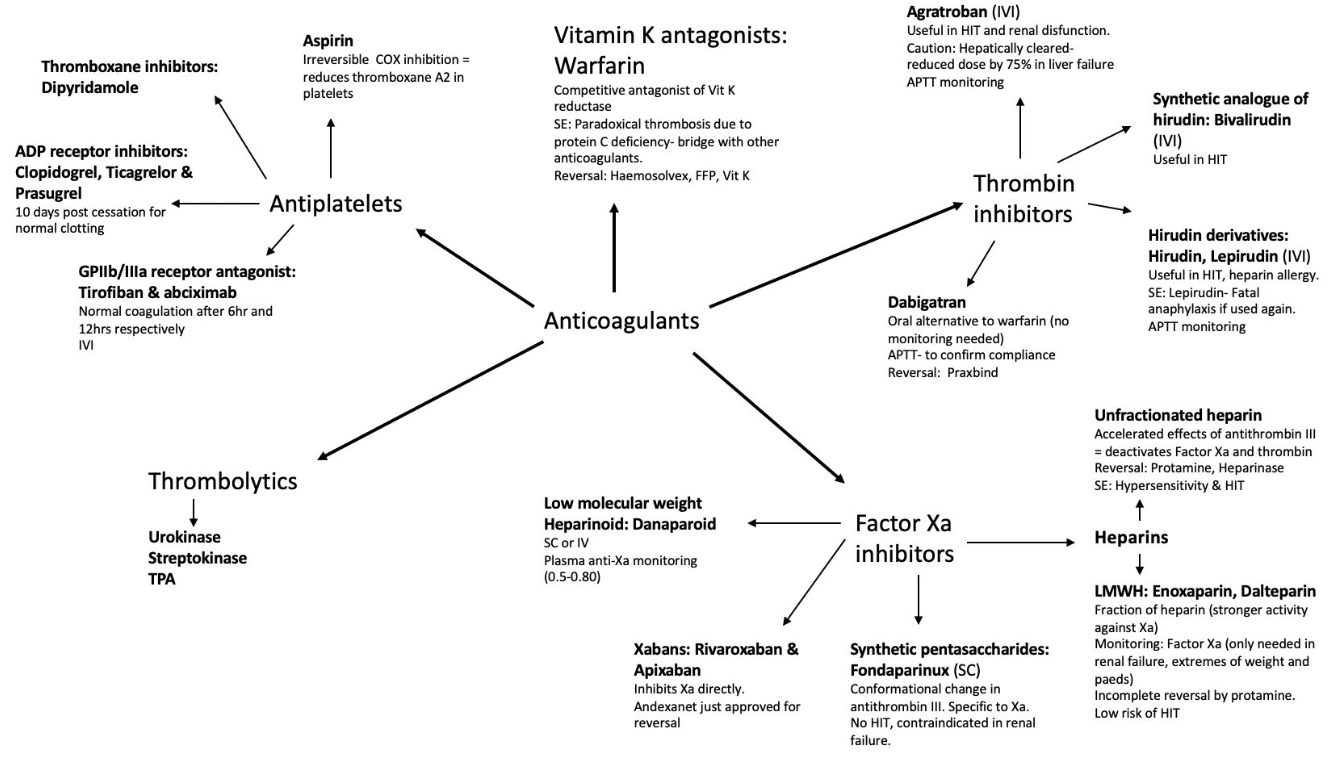

- Classification

- Drugs

- Protamine Sulphate

- Bridging & Reversal (evidence-based algorithm)

- Risk Stratification for Perioperative Thromboembolic Events

- Risk Stratification for Procedural Bleeding

- Procedural risk for Bleeding

- Perioperative Anticoagulation Management Protocol

- When Bridging Is Not Required

- 2. Low Thrombotic Risk + High Bleeding Risk Procedures or High HASBLED Score

- Antenatal VTE-risk Assessment (apply at Booking, at 28 Weeks, on Admission & postpartum)

- LMWH Dosing in Pregnancy for VTE Prophylaxis (RCOG / CHEST 2022)

- Elective Peripartum Management of Anticoagulation Therapy in Pregnant Women with Prosthetic Heart Valves

- Timing of Neuraxial Block & Catheter Removal (pregnancy-specific)

- Post-partum Prophylaxis

- Regional-to-General Conversion during Labour

{}

Classification

Drugs

Warfarin

Indications

- Prophylaxis of systemic thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation (AF), rheumatic valve disease, prosthetic valves.

- Prophylaxis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

Mechanism of Action (MOA)

- Inhibits Vitamin K Epoxide Reductase: Prevents recycling of oxidized vitamin K to its reduced form.

- γ-Carboxylation: Inhibits activation of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X in the liver.

Onset of Action (OOA)

- Circulating factors unaffected → Peak effect in 48-72 hours.

Adverse Effects (AEs)

- Haemorrhage

- Teratogenicity (especially in the first trimester)

Interactions

- Potentiated By:

- Coagulation-affecting Drugs: NSAIDs, Heparin.

- Plasma Binding Competition: NSAIDs.

- Metabolism Inhibition: Cimetidine, alcohol, allopurinol, ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, TCAs.

- Vitamin K Absorption Interference: Cholestyramine.

- Antagonized By:

- Hepatic Enzyme Induction: Barbiturates, rifampicin, carbamazepine.

Monitoring

- INR (International Normalized Ratio): Target INR: 2.0 to 4.5 depending on the indication.

Bridging

- Delay Resumption: Until adequate haemostasis is achieved.

- Major Surgery: LMWH/UFH. Reinitiate 48-72h post-op.

- Minor Surgery: LMWH/UFH. Reinitiate 24h post-op.

- Warfarin: Can resume same day as heparin; discontinue heparin when INR is therapeutic.

Reversal

- Stop Warfarin

- Vitamin K₁: 5 to 10mg oral (24h) or IV (6-8h) for clotting factor activation.

- PCC (Prothrombin Complex Concentrate): Replaces clotting factors in 15 minutes.

- FFP (Fresh Frozen Plasma): Replaces clotting factors in 1-4 hours.

Procoagulant Effect

Mechanism and Clinical Application

- Vitamin K-Dependent Clotting Factors: Warfarin inhibits the synthesis of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, and X) by inhibiting the enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase. This enzyme is essential for recycling vitamin K, which is necessary for the carboxylation and activation of these clotting factors.

- Protein C and Protein S: Warfarin also inhibits the synthesis of natural anticoagulants, Protein C and Protein S, which are also vitamin K-dependent. Protein C, when activated (as activated protein C or APC), degrades Factors Va and VIIIa, reducing thrombin formation and clot propagation. Protein S acts as a cofactor for activated Protein C.

- Short Half-Life of Protein C: Protein C has a shorter half-life (6-8 hours) compared to clotting factors like Factor II (prothrombin), which has a half-life of approximately 60-72 hours. As a result, the levels of Protein C decrease more rapidly after warfarin initiation.

- Temporary Hypercoagulable State: The rapid decline in Protein C levels, without an immediate corresponding decrease in the levels of clotting factors, creates a temporary hypercoagulable state. This procoagulant effect is particularly significant in the early days of warfarin therapy, before the full anticoagulant effect is achieved.

- Risk of Thrombosis: The initial procoagulant state can increase the risk of thrombosis, especially in patients with pre-existing hypercoagulable conditions.

- Bridging Therapy: To mitigate this risk, warfarin is often started alongside a fast-acting parenteral anticoagulant like heparin or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) until therapeutic INR (International Normalized Ratio) is achieved and the clotting factors are sufficiently reduced.

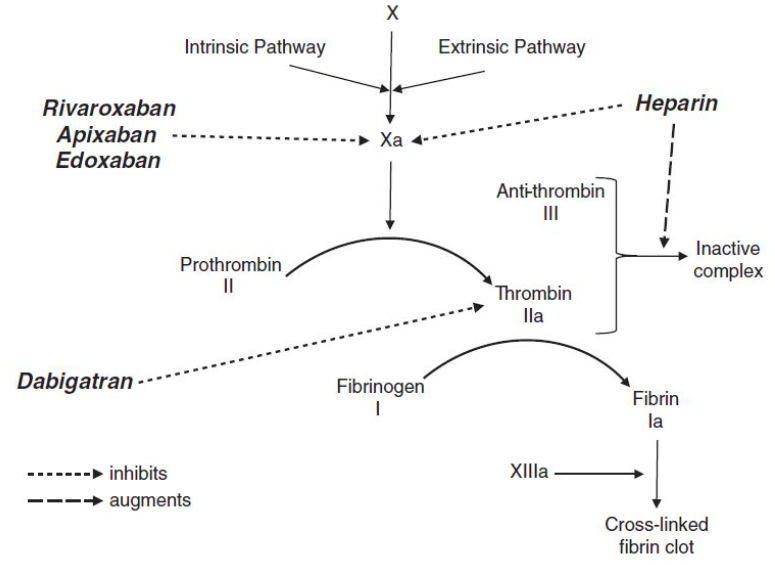

Heparins

Antithrombin III: Normally deactivates thrombin (by forming inactive complexes) and factor Xa.

Types

a) Unfractionated Heparin (UFH):

- Promotes the formation of inactive antithrombin-thrombin complexes by 1000-fold.

- Inhibits factor Xa at low doses, and factors IXa, XIa, and XIIa at higher doses.

b) Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) (e.g., enoxaparin, dalteparin, tinzaparin):

- Preferentially inhibits factor Xa much more than forming inactive complexes.

c) Fondaparinux:

- Selectively inhibits factor Xa.

- No effect on inactive complex formation.

Risk Factors and Prevention for Spinal Hematoma with LMWH

- Female sex, advancing age, renal insufficiency, spinal stenosis/ankylosing spondylitis, traumatic placement, indwelling epidural catheter, epidural–spinal, immediate preoperative (or intraoperative) drug administration, twice daily drug dosing, and concurrent antiplatelet or anticoagulation medications.

- Patients receiving a prophylactic dose of LMWH (eg, enoxaparin 40 mg SC OD) should have a delay of 12 hours prior to neuraxial anesthesia and prior to epidural catheter removal. A delay of 24 hours is required for those patients receiving higher therapeutic doses (eg, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID or 1.5 mg/kg OD)

- Indwelling catheters should be removed prior to initiation of LMWH thromboprophylaxis. In the postoperative period following neuraxial anesthesia, some patients, however, will require continued dosing. The first dose of postoperative LMWH may be administered 12 hours later for single daily prophylactic dosing, 24 hours later for therapeutic dosing, and 48–72 hours later after high bleeding risk surgery. Indwelling catheters should be removed 2 hours prior to the first dose. The administration of LMWH should be delayed for at least 4 hours following catheter removal.

Oral Anticoagulants

(a) Direct thrombin inhibitors (Dabigatran)

(b) Direct Factor Xa inhibitors (Rivaroxaban, Apixaban)

(c) Anti-Vitamin K (Warfarin)

DOAC Coagulation Tests

| DOAC | Likely Rules in Drug Effect | Rule out Drug Effect (Best Test) |

|---|---|---|

| Rivaroxaban (Xarelto), Apixaban (Eliquis), Edoxaban (Lixiana) | ↑ INR | Anti-Xa Level within normal limits |

| Dabigatran (Pradaxa) | ↑ PTT | DTT (Dilute Thrombin Time) within normal limits |

Summary:

- For Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, and Edoxaban: An increased INR suggests the drug effect, while a normal Anti-Xa level can rule it out.

- For Dabigatran: An increased PTT suggests the drug effect, while a normal DTT can rule it out.

Summary of DOAC Perioperative Management (Stopping and Restarting treatment)

- Elective surgery

- Low bleeding risk surgery: 24h; 48h in renal impairment

- High: 48h-72h; 72h in renal impairment, 96h for dabigatran

- Restart 1 day after low risk bleeding surgery and 2 days after high risk (PAUSE trial)

- Emergency Surgery

- Delay when possible to until levels fall

- Avoid neuraxial if anticoagulant effect cannot be ruled out

- TXA to ↓ surgical bleeding

- Consider specific reversal agent / PCC

Benefits and Weaknesses of Warfarin Compared with DOACs

Advantages:

- Wide range of indications

- Preferred in high-risk patients (e.g., mechanical valves)

- Long safety history

- Cheap, widely available antidote

- Easy monitoring of anticoagulation

- No gastrointestinal upset (compared to DOACs like dabigatran/rivaroxaban)

- Inexpensive

- Single daily dose

Disadvantages:

- Requires regular monitoring

- Highly variable dosing

- Increased need for bridging

- Food and drug interactions

- Initially procoagulant

- Slow onset of action

- Long half-life

- Increased risk of intracranial bleed (50%)

- Possibly increased risk of life-threatening bleed (25%)

Management of Patients with Acute Hip Fracture: Spinal Anaesthesia and DOACs

Thrombin Inhibitors (Dabigatran)

- Schedule for afternoon surgery the day after the last dose.

- Measure thrombin time at 08:00 on the day of surgery.

- Normal Thrombin Time: Proceed with surgery.

- Prolonged Thrombin Time: Contact hematologist; consider reversal with idarucizumab.

Factor Xa Inhibitors (Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, Edoxaban)

- CrCl ≥ 30 ml/min: Proceed 24 hours after the last dose.

- CrCl < 30 ml/min: Measure anti-factor Xa levels and consult with a hematologist before proceeding or delay surgery.

Protamine Sulphate

i) MOA: Prepared from fish sperm → negatively charged protein forms an inactive complex with Heparin that is cleared by the reticulo-endothelial system

ii) Dose: 1mg Protamine reverses 100 iu Heparin

iii) AE’s: Histamine release → allergy → hypotension, dyspnea, bradycardia; flushing; pulmonary hypertension; anticoagulant at high doses

iv) Alternatives: Platelet Factor 4, Heparinase

v) Heparin Rebound: After protamine-reversal, heparin can still be released from protein binding sites

Bridging

- Evaluate the patient’s thromboembolic risk using CHA₂DS₂-VASc score, prosthetic valve characteristics, or history of recent thromboembolism. Assess procedural bleeding risk using HAS-BLED score and surgical complexity. Decide on interrupting anticoagulation by balancing thrombotic versus bleeding risks, with guidelines favouring uninterrupted therapy in low-bleed-risk procedures. Bridging anticoagulation is generally discouraged due to increased bleeding without significant reduction in thromboembolic events, except in high-risk situations like recent mechanical valves, recent thromboembolism, or recent coronary stenting.

Bridging & Reversal (evidence-based algorithm)

| Step | Action | Evidence highlights |

|---|---|---|

| 1–Risk-stratify thrombo-embolism (TE) | Very-high: • VTE < 6 wk • Stroke/TIA < 3 mo • Mechanical mitral or caged-ball/tilting-disc valve • APS with arterial event. High: Moderate: Low: |

ACC/AHA 2024 Table 14; ASRA-ESRA 2022. |

| 2–Assess surgical/neuraxial bleeding risk | High bleeding risk = neuraxial/deep plexus block, cancer surgery, major spine/brain/joint, vascular; Low = cataract, dental, ports. | ASRA 2025; PAUSE & BRIDGE trials. |

| 3–Decide on bridging | • Warfarin:

–No bridge for low/moderate TE risk (BRIDGE RCT ↑major bleed 3.2 % vs 1.3 %, no ↓TE). –Therapeutic LMWH bridge only in very-high / high TE risk and high-bleed procedures avoided; consider prophylactic LMWH instead. –Stop warfarin 5 d pre-block, start LMWH (1 mg kg⁻¹ BID or 1.5 mg kg⁻¹ OD) once INR < 2; give last LMWH dose ≥ 24 h pre-puncture (≥ 36 h if renal CrCl < 30 mL min⁻¹). |

BRIDGE RCT NEJM 2015; ACC/AHA 2024 Class III-Harm for routine bridging, Class 2a for high-risk only. |

| • DOACs (dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, betrixaban): Do not bridge–predictable short half-life; bridging adds bleeding without TE benefit (PAUSE trial major bleed 1.6 %, no LMWH). | PAUSE study; ACC 2024 “no role for heparin bridging for DOACs”. | |

| • Mechanical heart valves: –Mitral/older aortic valve → bridge with therapeutic LMWH. –Bileaflet aortic valve + no stroke/TIA and CHA₂DS₂-VASc < 5 → no bridge (low risk). |

ESC 2023 valvular guidance; ACC/AHA 2024. | |

| • Active cancer or APS: consider risk-adjusted LMWH bridge; observational QI study showed ↓bleeding with patient-tailored protocols vs blanket bridging. | BMC Anaesthesiol 2023 risk-adjusted bridging. | |

| 4–Post-operative LMWH “re-bridge” | Start once haemostasis secure: –Low-bleed procedure: 24 h (prophylactic) → escalate to therapeutic after 48 h. –High-bleed / neuraxial: wait ≥ 48 h; remove catheter first (see timing table). |

ASRA 2025; ACC/AHA 2024 |

| 5–Reversal for urgent block / bleed | • Warfarin: 4-factor PCC 25–50 IU kg⁻¹ + 5 mg IV vit K. • FXa inhibitors: Andexanet alfa (bolus + infusion) or PCC 50 IU kg⁻¹ if unavailable. • Dabigatran: Idarucizumab 5 g IV. • Heparins: Protamine (1 mg per 100 IU heparin in last 2 h; max 50 mg). Antiplatelet reversal: if life-saving neuraxial block or uncontrolled bleeding is required within the P2Y₁₂ wash-out period, transfuse 1 apheresis platelet concentrate (≈ 1 pool); repeat once if platelet inhibition persists. Evidence is limited; use only when no pharmacological alternative exists. |

ASRA-ESRA 2022; ESAIC 2021 pharmacology table. |

| 6–Suspected neuraxial haematoma | STAT neuro exam → stop anticoagulant → urgent MRI/CT → surgical decompression ≤ 8 h from symptom onset. | ASRA 2025 safety statement. |

- Ciraparantag (aripazine)–broad-spectrum reversal of heparins and DOACs; in phase-III trials (not yet licensed). Monitor guideline updates for future availability.*

- PAUSE management strategy (skip 0–2–2 days depending on bleed risk, no bridging) in 3 007 atrial-fibrillation patients produced major-bleed 1.6 %, arterial TE ≤ 0.5 %.

- Skip 0–2–2 days

- How long to withhold the DOAC before and after a procedure:

- 0 days: Low bleed-risk procedures (sometimes you don’t need to stop the DOAC).

- 2 days before and 2 days after: For high bleed-risk procedures.

- The timing varies based on the specific drug and renal function.

- The PAUSE trial showed that in patients with atrial fibrillation taking DOACs, temporarily stopping the anticoagulant for 0 to 2 days before and after surgery (based on bleeding risk) without using heparin bridging resulted in very low rates of major bleeding (1.6%) and arterial clots (<0.5%).

- Skip 0–2–2 days

- ACC 2024 review states:

- “Uninterrupted DOAC is preferred for some low-bleeding-risk procedures.”

- “Hold factor-Xa inhibitors 2 days and dabigatran 2-4 days for higher-risk surgery.”

- “There is no role for LMWH bridging for DOACs because the drug-free window is already short.”

- For high-bleeding-risk operations you simply pause the DOAC for the recommended 2 to 4-day window and restart 2–3 days later, without heparin bridging.

- For truly low-risk procedures most patients can stay on their DOAC (or at most skip a single dose).

Summary

- Bridging is reserved for very-high or select high thromboembolic (TE) risk patients on warfarin (e.g., mechanical mitral valve, recent VTE, recent stroke, APS). It is not used for DOACs because of their short, predictable half-life.

- Pre-procedure

- Stop warfarin 5 days before surgery. Start LMWH when INR < 2. Use therapeutic LMWH (e.g., enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID or 1.5 mg/kg daily) if bleeding risk is low, with the last dose ≥ 24 h before the procedure (≥ 36 h if CrCl < 30 mL/min).

- When bleeding risk is high but TE risk remains significant, switch to prophylactic LMWH (e.g., enoxaparin 40 mg daily) instead of full-dose bridging, stopping 24 h pre-procedure. This approach balances TE protection with bleeding risk.

- Post-procedure: Restart LMWH only once haemostasis is secure—after 24 h for low-bleed risk (start prophylactic then escalate to therapeutic at 48 h), or after ≥ 48 h for high-bleed/neuraxial cases.

- Resume warfarin as soon as oral intake allows and continue LMWH until INR is therapeutic.

Risk Stratification for Perioperative Thromboembolic Events

| Risk Category | Mechanical Heart Valve | Atrial Fibrillation | VTE |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Any mitral valve prosthesis, recent stroke/TIA | CHADS₂ score of ≥6, recent stroke/TIA | Recent (within 3 months) VTE |

| Moderate | Bileaflet aortic valve with AF or risk factors | CHADS₂ score of 4-5 | VTE within past 3-12 months |

| Low | Bileaflet aortic valve without AF or risk factors | CHADS₂ score of ≤3 | Single VTE >12 months earlier |

Other High Risk: Anterior wall MI.

Bridging Recommendation

- High Risk Thrombosis: Likely benefit.

- Moderate Risk Thrombosis: Uncertain.

- Low Risk Thrombosis: Probably no benefit, increased bleeding risk.

- Device Placement (e.g., Pacemaker, Defibrillator): High risk bridging compared to continuing anticoagulation increases bleeding risk.

BRIDGE Trial:

- Findings: In patients with AF (intermediate/low thrombotic risk), no inferiority without bridging; higher bleeding risk with bridging (bridging = LMWH)

Risk Stratification for Procedural Bleeding

“HAS-BLED” Score for Assessing Bleeding Risk in Anticoagulation

- H: Hypertension

- A: Abnormal renal/liver function

- S: Stroke

- B: Bleeding history/predisposition

- L: Labile INR

- E: Elderly

- D: Drugs/alcohol

Score Interpretation:

- More than 3: High bleeding risk.

Procedural risk for Bleeding

Evidence-Based Procedure Bleeding Risk Classification

| Bleeding Risk Category | Procedure Examples |

|---|---|

| Low‑Bleeding Risk | Minor dental procedures (e.g. extraction, restoration) Cataract removal Skin biopsy Joint injection Diagnostic endoscopy (e.g. colonoscopy without polypectomy) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy |

| High‑Bleeding Risk | Any procedure with neuraxial anesthesia (e.g. epidural, spinal) Major intracranial or spinal surgery Major cardiac surgery (e.g. valve replacement) Major vascular or abdominopelvic surgery (e.g. CEA, cancer resections) Major orthopedic surgery (e.g. hip/knee arthroplasty) Reconstructive surgery or any procedure > 45 minutes |

Procedures where DOAC’s Doesnt Need to Be Stopped

- Minor dental procedures (e.g., extractions of up to 3 teeth, restorations, cleanings)—anticoagulation continued safely with local hemostatic measures; stopping increases thromboembolic risk without reducing bleeding

- Skin biopsies and other minor dermatologic procedures, including small excisions—bleeding risk is low, so anticoagulants typically continued

- Cataract surgery and other simple ophthalmic procedures—continuation is generally safe with minimal bleeding risk

- Diagnostic endoscopy without biopsy, such as routine colonoscopy or upper GI evaluation—minimal risk; anticoagulants often not interrupted

- Pacemaker or ICD implantation—trials (e.g. BRUISE CONTROL) support continuation of warfarin or DOACs to reduce pocket hematoma compared to interrupted/bridged strategies

- Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation—uninterrupted DOAC or warfarin has low complication rates and is preferred over interruption strategies

Summary

- The PAUSE protocol divides procedures into low (≈2/3 of cases) and high bleeding risk (≈1/3) categories, guiding DOAC interruption and resumption times accordingly

- ASRA 2025 guidelines classify neuraxial and deep regional procedures as high bleeding risk, requiring stringent anticoagulant interruption and monitoring prior to needle or catheter placement

- Management timelines:

- Low-risk procedures: interrupt DOACs ~1 day before, resume ~24 hours after.

- High-risk procedures: interrupt for ~2 days (or longer depending on renal function), resume ~48–72 hours post-o

Perioperative Anticoagulation Management Protocol

1. Assess Thromboembolic Risk

- High Risk (Consider bridging):

- Mechanical heart valve (especially mitral)

- Recent (<3 months) stroke, TIA, Anterior wall MI or VTE

- CHA₂DS₂-VASc score ≥6

- Severe thrombophilia (e.g., antiphospholipid syndrome)

- Moderate Risk (Individualized approach):

- CHA₂DS₂-VASc score 4–5

- VTE within the past 3–12 months

- Non-severe thrombophilia

- Low Risk (Bridging generally not recommended):

- CHA₂DS₂-VASc score ≤3

- VTE >12 months ago without additional risk factors

2. Assess Bleeding Risk of Procedure

- High Bleeding Risk Procedures:

- Major surgeries (e.g., cardiac, neurosurgical)

- Procedures involving highly vascular organs

- Low Bleeding Risk Procedures:

- Minor dental procedures

- Cataract surgery

- Dermatologic procedures

3. Management for Warfarin (Vitamin K Antagonists)

- Preoperative:

- Stop warfarin 5 days before surgery.

- When INR falls below therapeutic range, initiate bridging with LMWH or UFH if indicated. Alternatively initiate LMWH (Therapeutic) three days before surgery

- Test INR 1 day prior to surgery

- Stop LMWH 24 hours before surgery; stop UFH 4–6 hours before surgery.

- Postoperative:

- For low bleeding risk: resume LMWH or UFH 24 hours after surgery and restart warfarin concurrently.

- For high bleeding risk: delay resumption of LMWH or UFH for 48–72 hours; restart warfarin when hemostasis is secured.

4. Management for Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs)

-

Preoperative:

- Stop DOACs 1–2 days before low bleeding risk procedures.

- Stop DOACs 2–4 days before high bleeding risk procedures or if renal impairment is present.

-

Postoperative:

- For low bleeding risk: resume DOACs approximately 24 hours after surgery.

- For high bleeding risk: resume DOACs 48–72 hours after surgery, once hemostasis is secured.

When Bridging Is Not Required

1. Low Thrombotic Risk + Low Bleeding Risk Procedures

- Warfarin: Continue without interruption; monitor INR.

- DOACs: Continue or skip one dose only if needed.

- Examples: Minor dental, skin, eye procedures; pacemaker insertions; diagnostic endoscopy.

2. Low Thrombotic Risk + High Bleeding Risk Procedures or High HASBLED Score

- Warfarin:

- Stop 5 days before surgery.

- Ensure INR <1.5 before procedure.

- No bridging needed.

- Resume 12–24 hrs post-op once bleeding risk is low.

- DOACs:

- Stop 2–5 days before surgery depending on agent and renal function.

- No bridging needed.

- Resume 48–72 hrs post-op after bleeding risk subsides.

Anticoagulation in Patients with Previous HIT (Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia)

- Short-term Heparin Use: Potentially safe in emergencies.

- Alternative Anticoagulants: Preferred.

- Bivalirudin: Considered for PCI (Percutaneous Coronary Intervention).

Example Regimen for Previous HIT

- Initial: Bivalirudin.

- Follow-up: Alternative anticoagulants as per clinical guidelines.

Basic Approach to Anticoagulation and regional/ Blocks

Quick 4-Step Safety Screen

- Patient: bleeding diathesis, renal/hepatic failure, age > 65 yr, concurrent antiplatelet.

- Drug: half-life, low vs high-dose*, renal clearance, specific antidote.

- Procedure:

- Low risk = superficial, compressible (e.g. fascia iliaca, TAP).

- Intermediate = deep non-compressible (e.g. paravertebral, ESP, shoulder catheter).

- High risk = neuraxial, psoas compartment, deep cervical/axillary, interlaminar injections.

- Rescue–24 h staffed ward neuro-checks, MRI ± decompression reachable ≤ 8 h.

- ASRA 2025 replaces “prophylactic/therapeutic” with low-dose (VTE prophylaxis) and high-dose (treatment or twice-daily schedule).

The Catheter Removal Window

- The minimum safe interval that must elapse between the patient’s last dose of a specific antithrombotic-/antiplatelet agent and the physical removal of an indwelling neuraxial or deep-plexus catheter (e.g. epidural, continuous paravertebral, femoral, or brachial plexus catheter).

- Why it matters

- Removing the catheter during peak (or even residual) anticoagulant effect markedly increases the risk of spinal or deep-tissue haematoma.

- Observing the recommended window allows enough drug clearance (often ≥2–3 half-lives, or a verified normal coagulation test) so that clotting function has returned to a level that makes bleeding complications highly unlikely.

- Practical use

- Note last dose time of the anticoagulant/antiplatelet.

- Count forward the guideline-specified interval (e.g. 24 h for LMWH therapeutic dose, 24 h for most DOACs).

- Remove catheter only after that point, provided the patient shows no additional bleeding risk factors and (if indicated) coagulation tests are within normal limits.

- After removal, delay the next anticoagulant dose by the further interval shown in the table (e.g. ≥6 h) to let the puncture track seal.

Guideline Tables

- To minimise spinal / epidural haematoma you must treat two separate clocks for every antithrombotic agent:

- “Hold-to-block / catheter-removal” clock–how long you stop the drug before neuraxial puncture and before you pull an indwelling catheter.

- “Restart-after-removal” clock–the minimum delay after the catheter (or needle) leaves the epidural / intrathecal space before the next dose is given.

- The first clock protects against bleeding into the neuraxis during instrumentation; the second allows the dural or epidural track to seal once all hardware is out.

- Latest consensus statements (ASRA 2018, ESAIC–ESRA 2022, ASA practice advisories and NYSORA) agree that the restart interval is usually ≥ 6 h for antiplatelet drugs and ≥ 4–6 h (UFH/LMWH prophylaxis) to ≥ 6 h (DOACs/warfarin) for anticoagulants.

- Restarting sooner, or maintaining full-dose anticoagulation while a catheter remains in situ, is the commonest root cause of neuraxial haematoma in case series.

Antiplatelet & NSAID Timetable

| Agent | Stop before high-risk block | Catheter-removal window | Restart ≥ this many h after catheter removal | First postoperative dose if no catheter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin ≤ 325 mg day⁻¹ | Continue (stop 3 d if ≥2 bleeding RF) | N/A | 0 h – can continue | 6 h |

| Non-selective NSAIDs | Continue | N/A | 0 h | 6 h |

| Clopidogrel | 5 d | ≥ 24 h after last dose | 6 h | 6 h |

| Prasugrel | 7 d | ≥ 24 h | 6 h | 6 h |

| Ticagrelor | 5 d | ≥ 24 h | 6 h | 6 h |

| Ticlopidine | 10 d | ≥ 24 h | 6 h | 6 h |

| Cangrelor | 3 h | 3 h | 8 h | 8 h |

| GP IIb/IIIa (abciximab) | 24h-48h | Contra-indicated | ≥ 24 h | ≥ 24 h |

| GP IIb/IIIa (eptifibatide/tirofiban) | 8-12 h | Contra-indicated | ≥ 24 h | ≥ 24 h |

| Dipyridamole ER | 24 h | Remove first | 6 h | 6 h |

| Cilostazol | 48 h | Remove first | 6 h | 6 h |

| Garlic / Ginkgo / Ginseng | No stop (document) | N/A | 0 h | – |

Sources: ASRA 2018, ESAIC-ESRA 2022, Stanford 2019 table, NYSORA tips

- Continuing low-dose aspirin is appropriate for most neuraxial and surgical cases except in surgeries in closed spaces (intracranial neurosurgery, intramedullary spine, posterior eye) often warrant holding aspirin 7–10 days prior due to catastrophic bleeding risk

- Consider stopping longer-half-life NSAIDs (piroxicam, etc.) in high-risk patients or if combined with other agents.

Anticoagulants–neuraxial & Deep-plexus Timing

| Agent | Stop before block | Catheter-removal window | Restart ≥ this many h after catheter removal | First postoperative dose if no catheter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFH 5 000 U SC q12/q8 | 4–6 h | 4–6 h (check aPTT) | 1 h | 1 h |

| UFH IV infusion | Stop 4–6 h; ∆aPTT | 4–6 h | 1 h | 1 h |

| LMWH prophylactic (40 mg qd OR 30 mg q12h) | 12 h | 12 h | 4 h | 6–12 h† |

| LMWH therapeutic (1 mg kg⁻¹ q12 OR 1.5 mg kg⁻¹ qd) | 24 h | 24 h | 4 h | ≥24 h (low bleed) / 48 h (high bleed) |

| Warfarin | Stop 5 d, ensure INR < 1.5 (≥40% factor activity) |

Remove when INR < 1.5 | 6 h | 6-12h. Evening of surgery (if haemostasis OK) |

| Dabigatran (CrCl > 80 / 50–80 / 30–50 mL min⁻¹) | 2 / 3 / 4–5 d | 72 h | 6 h | 24 h (VTE ppx) or ≥ 48 h (therapeutic) |

| Rivaroxaban / Apixaban / Edoxaban / Betrixaban | For full-dose DOAC (e.g. AF therapy) hold ~72 h. For low-dose prophylactic DOAC (e.g. rivaroxaban 10 mg daily), a 24–36 h hold may suffice in normal renal function | 24 h | 6 h | 24 h (VTE ppx) or ≥ 48 h (therapeutic) |

| Fondaparinux | 36–42 h | Avoid neuraxial catheter; if present, remove ≥ 36 h since last dose | 12 h | 6 h (single shot only) |

| IV direct thrombin in. (bivalirudin/argatroban) | Contra-indicated | Contra-indicated | – | – |

| Thrombolytics / fibrinolytics | Contra-indicated ≤ 72 h | — | 72 h & normal fibrinogen |

- Use calibrated anti-Xa or dTT/Etc assays to shorten interval when urgently required. (DOAC’s)

- † ESAIC-ESRA allow 6–8 h for once-daily prophylaxis; ASRA remains 12 h–adopt the stricter interval unless a local protocol allows shorter.

- Intervals from ASRA 5th ed 2025, ESRA–ESAIC 2021, and SASA 2019; choose the longer interval if imaging/neurosurgery access is delayed.

- Sources: ASRA 2018, GuidelineCentral summary 2024, ESAIC-ESRA 2022, Stanford 2019, OpenAnesthesia,

How to Interpret the Two Postoperative Clocks

| Scenario | What starts the clock | Why it matters | Typical interval* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Restart after surgery (no catheter left) | Skin closure or single-shot puncture (which ever comes last) | Ensures surgical haemostasis before systemic anticoagulation rises | See “First post-op dose” column |

| 2. Restart after indwelling catheter removal | Actual moment the epidural/spinal catheter leaves the space | Allows the needle/catheter track to seal and epidural veins to compress | See “Restart ≥ h after catheter removal” column |

*Always longer if high-bleeding surgery, renal impairment, or traumatic tap.

Post-Block Surveillance

- Q4-hour motor, sensory & back-pain checks × 24 h (neuraxial/deep catheters).

- Red flags (new weakness, saddle numbness, sphincter change) ⇒ urgent escalation.

Using Anticoagulants while a Neuraxial Catheter Remains in Situ

| Drug class | Permitted with catheter? | Essential safeguards |

|---|---|---|

| UFH SC ≤ 5 000 U q8–q12 | Yes | Dose ≤ 10 000 U day⁻¹; neuro-checks q4 h; remove catheter 4–6 h post-dose and restart ≥ 1 h later |

| UFH IV infusion | Discouraged | If unavoidable: keep aPTT < 2× control, stop infusion 4–6 h pre-removal, restart ≥ 1 h after |

| LMWH prophylaxis (40mg daily) | Yes | First postoperative dose ≥ 12 h after insertion; remove catheter ≥ 12 h after last dose; restart ≥ 4 h later; no additional antiplatelets |

| LMWH therapeutic (≥ 1 mg kg⁻¹ q12 h), Fondaparinux, DOACs, GP IIb/IIIa, thrombolytics | No | Convert to safer agent or delay until catheter out and restart window met |

| Warfarin (INR < 1.5) | Acceptable | Daily INR; pull catheter when INR < 1.5; restart ≥ 6 h post-removal |

- If you have a bloody or traumatic tap, extend every restart interval by ≥ 24 h and intensify neuro-checks (hourly × 24 h).

- When a patient genuinely needs therapeutic-dose anticoagulation (e.g., heparin infusion, therapeutic LMWH, warfarin with INR 2–3, or a DOAC at full strength) but also “needs an epidural,” modern guidelines make one point crystal-clear: continuous neuraxial catheterisation is normally incompatible with full anticoagulation.

- The clinician must either (1) de-escalate or interrupt the anticoagulant long enough to insert and later remove the catheter under guideline time-windows, or (2) abandon the epidural in favour of alternative analgesia or peripheral blocks.

- Low–moderate thrombotic risk (e.g., VTE > 3 months ago, AF without prosthetic valve):

- Hold therapeutic anticoagulation, convert temporarily to prophylactic LMWH (40 mg daily) or mini-dose UFH, and follow the standard neuraxial timing rules.

- High thrombotic risk (e.g., mechanical mitral valve, VTE < 30 days, LV assist device, acute coronary syndrome):

- Epidural catheter is usually abandoned. Use single-shot spinal or catheter-free peripheral/plane blocks plus multimodal systemic analgesia.

- Low–moderate thrombotic risk (e.g., VTE > 3 months ago, AF without prosthetic valve):

Obstetric Anticoagulation & Neuraxial Guidance

Antenatal VTE-risk Assessment (apply at Booking, at 28 Weeks, on Admission & postpartum)

| Risk tier (RCOG 37a 2022) | Typical factors | LMWH prophylaxis |

|---|---|---|

| Very high | Previous VTE + thrombophilia or > 1 previous VTE | Begin immediately antenatally (from confirmation of pregnancy) and continue for 6 weeks postpartum |

| High | Single previous VTE, high-risk thrombophilia, current ovarian hyper-stimulation syndrome, morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40) with ≥ 1 additional factor | Start from first trimester or as soon as diagnosis is made; continue for 6 weeks postpartum |

| Intermediate | ≥ 3 risk factors* (age ≥ 35, BMI ≥ 30, multiparity ≥ 3, IVF, smoker, medical comorbidity) | Start from 28 weeks and continue 10 days postpartum |

| Low | ≤ 2 risk factors | No routine LMWH; encourage mobilisation + hydration |

- Add transient factors (e.g. hospital admission, infection, long-haul flight) as they arise and escalate tier if cumulative score ≥ 3.

LMWH Dosing in Pregnancy for VTE Prophylaxis (RCOG / CHEST 2022)

| Booking weight | Prophylactic dose (enoxaparin) | Intermediate dose‡ | Therapeutic dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 50–< 90 kg | 40 mg SC OD | 40 mg SC BD | 1 mg kg⁻¹ SC BD |

| 90–< 120 kg | 40 mg SC BD | 60 mg SC BD | 1 mg kg⁻¹ SC BD |

| 120–< 150 kg | 60 mg SC BD | 80 mg SC BD | 1 mg kg⁻¹ SC BD |

| ≥ 150 kg | 80 mg SC BD (monitor anti-Xa 0.2–0.4 IU mL⁻¹) | 100 mg SC BD | 1 mg kg⁻¹ SC TDS ± monitoring |

- ‡Used after caesarean in BMI ≥ 40 kg m⁻² or multiple major risk factors.

- Fondaparinux and DOACs are contra-indicated antenatally; warfarin is teratogenic (avoid weeks 6–12) but acceptable during breastfeeding.

Elective Peripartum Management of Anticoagulation Therapy in Pregnant Women with Prosthetic Heart Valves

- Stop warfarin at 36/40 weeks and switch to dose-adjusted SC-LMWH. If unavailable, use UFH infusion.

- Last dose 24h before planned delivery at 38/40 weeks.

- Bridge to dose-adjusted IV-UFH or intermittent LMWH (prophylactic dose) with various regimens.

- Serial anti-Xa levels: 0.2 – 0.5 considered safe for vaginal or cesarean delivery.

- Recommence IV-UFH or anti-Xa-guided SC-LMWH 6 hours after uncomplicated delivery.

- Reintroduce warfarin on day 5 to 7 postpartum.

Timing of Neuraxial Block & Catheter Removal (pregnancy-specific)

| Anticoagulant | Last prophylactic dose → epidural / spinal | Therapeutic dose → epidural / spinal | Catheter removal | Restart after removal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMWH | ≥ 12 h | ≥ 24 h | ≥ 12 h after last prophylactic ≥ 24 h after last therapeutic |

≥ 4 h (prophylactic) ≥ 6 h (therapeutic) |

| UFH s.c. 5 000 IU BD/TID | ≥ 4 h | n/a (avoid high-dose antenatally) | ≥ 4 h | ≥ 1 h |

| Warfarin (postpartum only) | Contra-indicated before delivery | Convert to LMWH ≥ 5 d before | When INR < 1.5 | Restart when haemostasis secure |

| Aspirin ≤ 150 mg | No restriction | — | No restriction | Continue |

| GP IIb/IIIa, DOACs, fondaparinux | Do NOT perform neuraxial–switch to LMWH | — | — | — |

- Lab tests: consider anti-Xa if BMI > 40 kg m⁻², renal impairment, or timing uncertain; safe threshold < 0.1 IU mL⁻¹.

Post-partum Prophylaxis

- All caesarean births with ≥ 1 additional risk factor: LMWH 10 days.

- VTE during pregnancy, very-/high-risk groups: LMWH or warfarin (target INR 2–3) for 6 weeks; DOACs suitable if not breastfeeding.

- Delay first LMWH dose: 4–6 h after vaginal delivery, 6–12 h after caesarean once bleeding controlled.

- Combine with IPC sleeves until fully mobile

Regional-to-General Conversion during Labour

- If spontaneous labour begins while on prophylactic LMWH: omit next dose and reassess epidural eligibility after 12 h.

- On therapeutic LMWH: advise elective induction 24 h after last dose or consider regional anaesthesia alternatives (CSE after 24 h + normal anti-Xa).

- Suspected PPH or need for urgent CS before interval elapsed–proceed under GA; reverse LMWH with protamine 1 mg per 1 mg enoxaparin (max 50 mg).

South-African Context

- SASA 2022 endorses RCOG thresholds but stresses limited access to anti-Xa assays; default to conservative 24 h interval for therapeutic LMWH before neuraxial when testing unavailable.

Key Take-aways

- Assess VTE risk at every maternity contact–pregnancy itself multiplies baseline risk ×4.

- Weight-adjust LMWH; monitor anti-Xa only if extremes of weight/renal dysfunction.

- Strict 12 h (prophylactic) / 24 h (therapeutic) rule around neuraxial; document timing in note

- Continue prophylaxis for 10 days after vaginal/CS in intermediate-risk, 6 weeks in high-risk.

- Warfarin safe in breastfeeding; DOACs only if formula-feeding.

Laboratory & Clinical Monitoring

- (Consolidated from ASRA 2025, ASRA–ESRA 2022, ESAIC/ESRA 2021 and SASA 2019)

When to Order Tests

| Situation | Recommended test(s) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Warfarin–before puncture or catheter removal | INR (target < 1.4) | Confirms adequate reversal/clearance. |

| IV unfractionated heparin (UFH) | aPTT or ACT within normal range | Short half-life but high inter-patient variability. |

| SC UFH ≥ 4 days, any dose | Platelet count | Detect heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). |

| Therapeutic or prolonged LMWH (> 4 days) | Platelet count ± anti-Xa (selected cases*) | Screen for HIT; anti-Xa if obesity, pregnancy, renal failure, or high-bleed surgery. |

| Fondaparinux / DOAC (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban)—unexpected dosing with indwelling catheter | Drug-specific anti-Xa assay | Assesses residual activity when timing uncertain. |

| Dabigatran—renal impairment or timing uncertainty | Dilute thrombin time (dTT) or ecarin clotting time (Etc) | Sensitive to dabigatran concentration. |

| Thrombolytics / fibrinolytics | Fibrinogen level (> 1.5 g L⁻¹) & global coagulation screen | Ensure return of clotting factors before neuraxial access. |

| Suspected coagulopathy (liver failure, massive transfusion) | Full blood count, PT/INR, aPTT, fibrinogen, viscoelastic test (ROTEM/TEG) | Comprehensive assessment of acquired disorders. |

- *Anti-Xa target 0.1–0.3 IU mL⁻¹ (prophylactic), 0.5–1.0 IU mL⁻¹ (therapeutic).

- DOAC and Fondaparinux: Anti-Xa assay must be calibrated to the specific factor-Xa inhibitor.

Situations Where Routine Testing Is Not Required

- Aspirin, NSAIDs, clopidogrel and other antiplatelets (platelet-function assays add no clinical value).

- Prophylactic low-dose SC UFH (≤ 5 000 IU BID/TID) unless therapy > 4 days.

- Standard prophylactic LMWH in patients with normal renal function and body habitus.

- Direct oral anticoagulants if timing since last dose is clearly > 5 half-lives and renal function is normal.

Renal & Hepatic Function Considerations

- Estimate creatinine clearance before scheduling dabigatran or DOAC interruption; extend holding period if CrCl < 50 mL min⁻¹.

- Liver function tests for patients on warfarin, rivaroxaban or apixaban with suspected hepatic impairment.

Using Labs to Guide Blocks

| Drug / situation | “Fit-to-block” laboratory target* | When to order | Evidence & caveats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | INR ≤ 1.4 (ideally ≤ 1.1) | – Timing unclear (unknown last dose) – INR still > 1.5 on planned day |

Threshold derived from pooled case reports and expert consensus; bleeding risk rises steeply once INR > 1.5, especially with neuraxial techniques. |

| IV unfractionated heparin | Normal aPTT or ACT < 120 s | – High-dose infusion stopped ≤ 4 h ago | Short half-life but large inter-patient variability justifies a single check before puncture/catheter removal. |

| LMWH (therapeutic or prolonged use) | Anti-Xa < 0.1 IU mL⁻¹ (prophylactic range) | – BMI > 35 kg m⁻², eGFR < 30 mL min⁻¹, pregnancy, or urgent/unsure timing | Anti-Xa sampling 4 h post-dose; below cut-off correlates with minimal residual anticoagulation, but routine testing not cost-effective for standard patients. |

| Factor-Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, betrixaban, fondaparinux) | Drug-calibrated anti-Xa < 30 ng mL⁻¹† | – Last dose < guideline interval – Accidental in-hospital dose with catheter in situ |

Anti-Xa assays must be agent-specific; correlate reasonably with plasma concentration but no randomised outcome data—use only when timing is uncertain. |

| Dabigatran | dTT < 34 s or Etc < 40 s | – Impaired renal function – Last dose < suggested hold-time |

dTT/Etc highly sensitive for residual drug; safe thresholds extrapolated from cohort studies. |

| Post-fibrinolytic therapy | Fibrinogen > 1.5 g L⁻¹ and PT/aPTT normal | – < 72 h since alteplase/streptokinase | Low fibrinogen predicts ongoing lysis and high bleeding risk; wait ≥ 48 h and document normalisation. |

| Heparin (IV or SC) ≥ 4 d | Platelets > 100 × 10⁹ L⁻¹ | – Screen for HIT | Drop > 50 % from baseline or < 100 × 10⁹ L⁻¹ warrants HIT work-up and deferral of block. |

| Viscoelastic tests (TEG/ROTEM) | Not validated for anticoagulant quantification | — | CT/ACT values poorly correlate with DOAC or LMWH levels; cannot be relied on to override guideline timing. |

| Platelet-function assays (e.g. PFA-100, VerifyNow) | Not recommended | — | Do not predict spinal haematoma risk; add cost without improving safety. |

- *Values reflect the consensus position of ASRA 2025, ASRA-ESRA 2022 and ESAIC/ESRA 2021; laboratories should confirm local reference ranges.

- †Many centres use 30 ng mL⁻¹ as a pragmatic threshold; no outcome‐validated cut-off exists.

- Safe neuraxial threshold: drug-calibrated anti-Xa < 25–30 ng mL⁻¹ (rivaroxaban/apixaban/edoxaban). Validate with the local laboratory and document result before proceeding.

Practical Take-aways

- Timing first, labs second. When the interval since the last dose is clear and kidney function normal, guideline hold-times remain the safest trigger to proceed; tests add little.

- Use a test when timing is uncertain or compressed. A single INR, aPTT/ACT, anti-Xa or dTT/Etc can confirm drug clearance and avoid unnecessary delay—or flag residual activity that mandates postponement.

- Assay must match the drug. A generic anti-Xa assay will under-estimate apixaban or rivaroxaban; insist on a drug-calibrated test or do not rely on the result.

- Normal result ≠ zero risk. Even with reassuring labs, maintain 4-hourly neuro-checks for 24 h after neuraxial or deep blocks.

- Do not use platelet-function or viscoelastic tests to “shortcut” recommended intervals. Current evidence does not support their predictive value for spinal haematoma.

Post-Block Clinical Monitoring

- Neurological checks (motor power, sensory level, back pain) q4 h for 24 h after neuraxial or deep-plexus block in any anticoagulated patient.

- Continue until 12 h after last high-dose anticoagulant or after catheter removal plus next safe anticoagulant dose, whichever is longer.

- Immediate MRI and neurosurgical referral if red-flag symptoms arise.

- If HIT is confirmed (platelet drop ≥ 50 % or < 100 ×10⁹ L⁻¹ and positive PF4 assay), stop all heparins, start argatroban or fondaparinux, and defer neuraxial or deep plexus block until platelet recovery and stable alternative anticoagulation are achieved.

Patients on Dual Antiplatelet Therapy

| Scenario | Current recommendation (ACC / AHA peri-operative guideline 2024) | Key peri-operative antiplatelet points |

|---|---|---|

| Balloon angioplasty without stent | Postpone elective non-cardiac surgery (NCS) ≥ 14 days after procedure if ≥ 1 antiplatelet drug would need to be stopped. | Continue aspirin 75–100 mg day⁻¹ where possible. |

| Bare-metal stent (BMS) | > 30 days after PCI before interrupting any component of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). Surgery within 30 days is potentially harmful. | If surgery cannot be delayed to ≥ 30 days, keep full DAPT (aspirin + P2Y₁₂ inhibitor) unless life-threatening bleeding risk. Bridging with i.v. cangrelor may be considered when DAPT interruption is unavoidable. |

| Drug-eluting stent (DES)–placed for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) | Defer elective NCS ≥ 12 months if interruption of ≥ 1 antiplatelet agent is required. | Within 12 months keep DAPT if surgery must proceed; weigh bleeding vs stent-thrombosis risk in a multidisciplinary forum. |

| DES–placed for chronic coronary disease (stable CAD) | Defer elective NCS ≥ 6 months. If the risk of delaying surgery exceeds cardiac risk, NCS may be considered ≥ 3 months after PCI when a short (≤ 5 day) interruption of the P2Y₁₂ inhibitor is essential. | Aspirin should be continued; stop clopidogrel/ticagrelor 5 days (prasugrel 7 days) before surgery if absolutely required, and restart as soon as haemostasis permits (within 24 h is preferred). |

| Any PCI ≤ 30 days (BMS or DES) requiring antiplatelet interruption | Elective NCS is strongly discouraged because of very high stent-thrombosis risk. | Proceed only if life-saving surgery; maintain DAPT throughout or arrange i.v. bridging (e.g. cangrelor). |

| High cardiac-risk patients without stent (e.g. recent MI, high CHADS-VASc) | Continue aspirin peri-operatively; withhold clopidogrel/prasugrel/ticagrelor for 5–7 days if surgical bleeding risk is high, then restart within 24 h once haemostasis secured. | Applies to open vascular, major spine or intracranial procedures where bleeding consequences are extreme. |

| Low cardiac-risk patients without stent | Discontinue P2Y₁₂ inhibitor 5–7 days before surgery; consider stopping aspirin if bleeding risk outweighs ischaemic benefit, then restart antiplatelet(s) within 24 h post-op. | Routine “cover” with aspirin in patients who were never on it is not beneficial. |

Clinical Pearls

- Aspirin 75–100 mg day⁻¹ should be continued in almost all patients with previous PCI unless surgical bleeding risk is extreme.

- If a P2Y₁₂ inhibitor must be paused in a patient with a stent < 6 months old (DES) or < 30 days old (BMS), consider short-acting i.v. cangrelor bridging.

- Decisions should be multidisciplinary, balancing haemorrhage risk, stent-thrombosis risk and the consequences of delaying surgery.

Peri-operative Venous Thrombo-embolism (VTE) Prophylaxis

Risk Assessment Framework

Caprini Venous Thrombo-embolism (VTE) Risk Assessment Model (2021 update)

| Points | Risk factor |

|---|---|

| 1 point | Age 41–60 yr • Minor surgery (<45 min) • BMI ≥ 25 kg m⁻² • Swollen ankles (current) • Varicose veins • Sepsis (<1 mo) • Pregnancy or ≤ 1 mo post-partum • Oral contraceptives or HRT • History of unexplained/recurrent miscarriages • Abnormal pulmonary function (COPD, asthma) • Acute myocardial infarction (<1 mo) • Congestive heart failure (<1 mo) • Bed rest > 72 h • Immobility (limb cast, paralysis) |

| 2 points | Age 61–74 yr • Arthroscopic or laparoscopic surgery ≥ 45 min • Major open surgery < 45 min • Malignancy (active or within 1 yr) • Confined to bed (>72 h) with plaster immobilisation • Central venous access • Inflammatory bowel disease • Chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 6 mo |

| 3 points | Age ≥ 75 yr • Major surgery ≥ 45 min • Emergency abdominal or thoracic surgery • History of VTE (DVT/PE) • Known thrombophilia • Stroke (<1 mo) • Acute spinal-cord injury (<1 mo) • Chronic kidney disease (eGFR < 30 mL min⁻¹) • Severe lung disease requiring oxygen |

| 5 points | Hip, pelvis or lower-limb fracture • Hip or knee arthroplasty • Major trauma (> 12 h) • Spinal surgery with instrumentation • Multiple major injuries • Elective neurosurgery • Acute leukaemia • Bone-marrow transplant |

Interpreting the Total Score (caprini Et Al. 2021)

| Total score | VTE risk category | Estimated post-operative VTE incidence without prophylaxis | Prophylaxis recommendation (CHEST 2022 / NICE NG89) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Very low | < 0.5 % | Early mobilisation only |

| 1–2 | Low | ~ 1 % | Mechanical prophylaxis (IPC or GCS); pharmacological cover usually not required |

| 3–4 | Moderate | 1–2 % | IPC ± GCS plus LMWH or low-dose UFH (unless contra-indicated) |

| ≥ 5 | High | 2–6 % (≥ 8 % if ≥ 8 points) | IPC ± GCS and LMWH/UFH or DOAC*; extend to 28–35 days after major cancer surgery or hip/knee arthroplasty |

- Applying the score:

- 0–2 (low): early mobilisation only.

- 3–4 (moderate): IPC ± GCS plus LMWH/UFH if bleeding risk is low.

- ≥ 5 (high): IPC + GCS and LMWH/UFH or DOAC; extend prophylaxis 28–35 days in hip/knee arthroplasty or major cancer surgery.

- ≥ 8 (very high): consider dual prophylaxis (mechanical + pharmacological) and extended 4-week course irrespective of procedure type.

- Add points cumulatively for all present risk factors at the time of surgery or hospital admission.

- The model predicts symptomatic DVT/PE and informs duration/intensity of prophylaxis.

- For day-case or minimally invasive procedures, use the score but consider shorter prophylaxis courses.

- The Caprini tool is validated across surgical specialties and endorsed by the American Society of Hematology (2023) and NICE (UK) for individualised risk assessment.

- Continue IPC/GCS until the patient ambulates independently ≥ 3 times/day or until hospital discharge, even when pharmacological prophylaxis has started.

Non-pharmacological Measures (all risk Tiers unless contraindicated)

| Modality | Start | Stop | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) | Before induction | On full mobile ambulation | First-line where pharmacological prophylaxis is delayed/contra-indicated. |

| Graduated compression stockings (GCS, 18 mm Hg) | Pre-op | Until discharge or patient mobile ≥ 3×/day | Ensure correct sizing; omit in severe PAD. |

| Early, aggressive mobilisation | Day 0 | Lifelong | Document in post-op orders; most cost-effective intervention. |

| Inferior vena-cava (IVC) filter | Only if anticoagulation absolutely impossible and acute proximal DVT/PE present | Remove when anticoagulation feasible | No role as primary prevention. |

Pharmacological Prophylaxis–Timing & Duration

| Drug (prophylactic dose) | First dose pre-/post-op | Daily schedule | Stop (standard) | Extended-duration indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enoxaparin 40 mg SC | Usual surgery: 2 h pre-incision or 6–12 h post-op if high bleeding risk / neuraxial catheter in situ | OD | Day 7–10 | Hip/knee arthroplasty, major cancer abdo/pelvis, lower-limb fracture: continue 28–35 d |

| Dalteparin 5 000 IU SC | 2 h pre or 6–12 h post | OD | Day 7–10 | Same as above |

| Fondaparinux 2.5 mg SC | ≥ 6 h post-skin closure | OD | Day 7–10 | Hip fracture surgery or cancer: extend to 28 d |

| Rivaroxaban 10 mg PO | 6–10 h post-op, once haemostasis secure | OD | Day 10–14 | Total hip replacement (THR): 35 d |

| Apixaban 2.5 mg PO | 12–24 h post-op | BD | Day 10–14 | THR: 35 d |

| UFH 5 000 IU SC | 2 h pre-incision | 8-hourly | Until mobile or switch to LMWH | Preferred in severe renal failure (CrCl < 15 mL min⁻¹) |

| Low-dose aspirin 75–100 mg PO | 6 h post-op | OD | Day 28–35 (orthopaedics) | AAOS-endorsed option for isolated THR/TKR where bleeding risk high |

- Key timing principles

- With neuraxial or deep plexus catheters: defer first LMWH/fondaparinux until ≥ 12 h after puncture; remove catheter ≥ 12 h after last prophylactic LMWH dose and ≥ 36 h after fondaparinux, then postpone next dose ≥ 4–6 h.

- Resume prophylaxis immediately if unexpected delay > 24 h and patient remains immobile.

- Re-assess daily: hold drug if active bleeding, platelets < 50 × 10⁹ L⁻¹ or spinal haematoma suspected.

Special Populations

| Group | Adjustment |

|---|---|

| Renal impairment (CrCl < 30 mL min⁻¹) | LMWH: halve dose or use UFH 5 000 IU 8-hourly; avoid fondaparinux. |

| Obesity (BMI > 40 kg m⁻²) | Enoxaparin 40 mg BD or weight-based 0.5 mg kg⁻¹ OD. If BMI: > 50 or weight > 150 kg.Check anti-Xa (goal 0.2–0.4 IU mL⁻¹) after 3rd dose |

| Pregnancy / puerperium | LMWH preferred; start 6 h post-C-section or 12 h post-vaginal delivery; continue 6 weeks if high risk. |

| Paediatric ≥ 12 y | Dalteparin 50 IU kg⁻¹ SC OD (max 5 000 IU). |

| South-African resource-limited settings | Prioritise mechanical prophylaxis + UFH where LMWH unaffordable; document daily mobility review (SASA Day-Case & Arthroplasty Guideli |

When to Omit or Stop Pharmacological VTE Prophylaxis

- Active intracranial or GI bleeding, platelet count < 50 × 10⁹ L⁻¹.

- Spinal/epidural haematoma suspicion–hold immediately and investigate.

- Neuraxial catheter in situ and insertion < 6 h ago (see timing table above).

- Epidural haematoma decompression surgery–restart only after neurosurgical clearance (usually ≥ 24–48 h).

Links

- Obstetrics Anticoagulation|Obstetrics Anticoagulation

- Clotting cascade

- Point of Care Coagulation testing

- Ortho regionals

- Anticoagulation and blocks

- Haematology and Blood testing

Past Exam Questions

Perioperative Coagulation Management in a Patient with a Subdural Haematoma

A 65-year-old patient with non-valvular atrial fibrillation on warfarin presents with a large subdural haematoma with a deteriorating level of consciousness. Her INR is found to be 9.

a) How will you manage this patient’s coagulation perioperatively? (6)

b) What would your approach be to re-institution of anticoagulation in this patient? (4)

References:

- McIlmoyle, K. and Tran, H. (2018). Perioperative management of oral anticoagulation. BJA Education, 18(9), 259-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2018.05.007

- Douketis, J. D., Spyropoulos, A. C., Duncan, J., Carrier, M., Gal, G. L., Tafur, A., … & Schulman, S. (2019). Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation receiving a direct oral anticoagulant. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(11), 1469. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2431

- Polania Gutierrez JJ, Rocuts KR. Perioperative Anticoagulation Management. [Updated 2023 Jan 23]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557590/

- Lamperti, M., Khozenko, A., & Kumar, A. (2019). Perioperative management of patients receiving new anticoagulants. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 25(19), 2149-2157. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612825666190709220449

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- Horlocker TT, Vandermeulen E, Kopp SL, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: ASRA evidence-based guidelines, 4th edition. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(3):263-309.

- Kopp SL, Vandermeulen E, Kumar R, et al. ASRA evidence-based guidelines: Regional anesthesia in patients receiving antithrombotic agents (5th edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2025;50(6):online ahead of print.

- Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano DA, et al. Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications: ASRA–ESRA guidelines 2022. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022;47(1):75-95.

- Gogarten W, Vandermeulen E, Van Aken H, et al. Regional anaesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: ESAIC/ESRA guidelines 2021. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2021;38(6):100-132

- South African Society of Anaesthesiologists (SASA). Neuraxial and plexus blocks in patients on antithrombotics–SASA guideline 2019. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2019;25(2):50-66.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation (BRIDGE trial). N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):823-833.

- Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Duncan J, et al. Perioperative management of patients with atrial fibrillation on apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban (PAUSE study). JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1469-1478.

- Caprini JA. Individualized risk assessment is the best strategy for thromboembolic prophylaxis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017;43(5):536-543

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NG89: Venous thromboembolism in over 16s: Reducing the risk in hospital and after discharge. London: NICE; 2018 (updated 2020).

- Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for inpatient and surgical prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3257-3814.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG). Reducing the risk of venous thrombosis in pregnancy and the puerperium (Green-top Guideline No. 37a). London: RCOG; 2022.

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 196: Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(1):e1-e17. (Reaffirmed 2023).

- Shnaider H, Shnaider A, Orbach-Zinger S, et al. Neuraxial anesthesia in obstetric patients receiving low-molecular-weight heparin: A systematic review. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2022;50:103287.

- ACC/AHA Task Force. 2024 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular management for noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 2024;150(2):e1-e128.

- Gerstein NS, Schulman PM, Gerstein WH, et al. Should more patients continue aspirin therapy perioperatively? Clinical impact of aspirin withdrawal in elective noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(3):777-787.

- Rossini R, et al. Perioperative management of patients on antiplatelet therapy: Joint consensus of SCAI, ACC, AHA (2017). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91(5):865-869.

- Anderson DR, Dunbar MJ, Bohm ER, et al. Aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip or knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):699-707.

- Baron TH, Kamath PS, McBane RD. Management of antithrombotic therapy in patients undergoing invasive procedures. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2113-2124. (Updated 2020 ACCP guidance).

- Kumar M, Bhandary S, Kaur R, et al. Aspirin interruption before neurosurgical interventions: a review of literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;157:55-60.

- Döhler I, Roder D, Schlesinger T, et al. Risk-adjusted perioperative bridging anticoagulation reduces bleeding complications: a propensity-score matched analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023;23(1):56.

- South African Society of Anaesthesiologists. Obstetric Anaesthesia Handbook. SAJAA 2022;28(Suppl 1):S1-S20.

Summaries:

Anticoagulants 01

Anticoagulants 02

Bleeding and clotting

Antiplatelet and stents

Coagulation testing

Stanford neuraxial guidelines

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved

id: “c124476c-1df0-4e5b-ab96-5378fc3a325d”