- Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB)

- Components and Function

- Harm from CPB

- Managing Bypass

- Anticoagulation Management for Adults Undergoing CPB

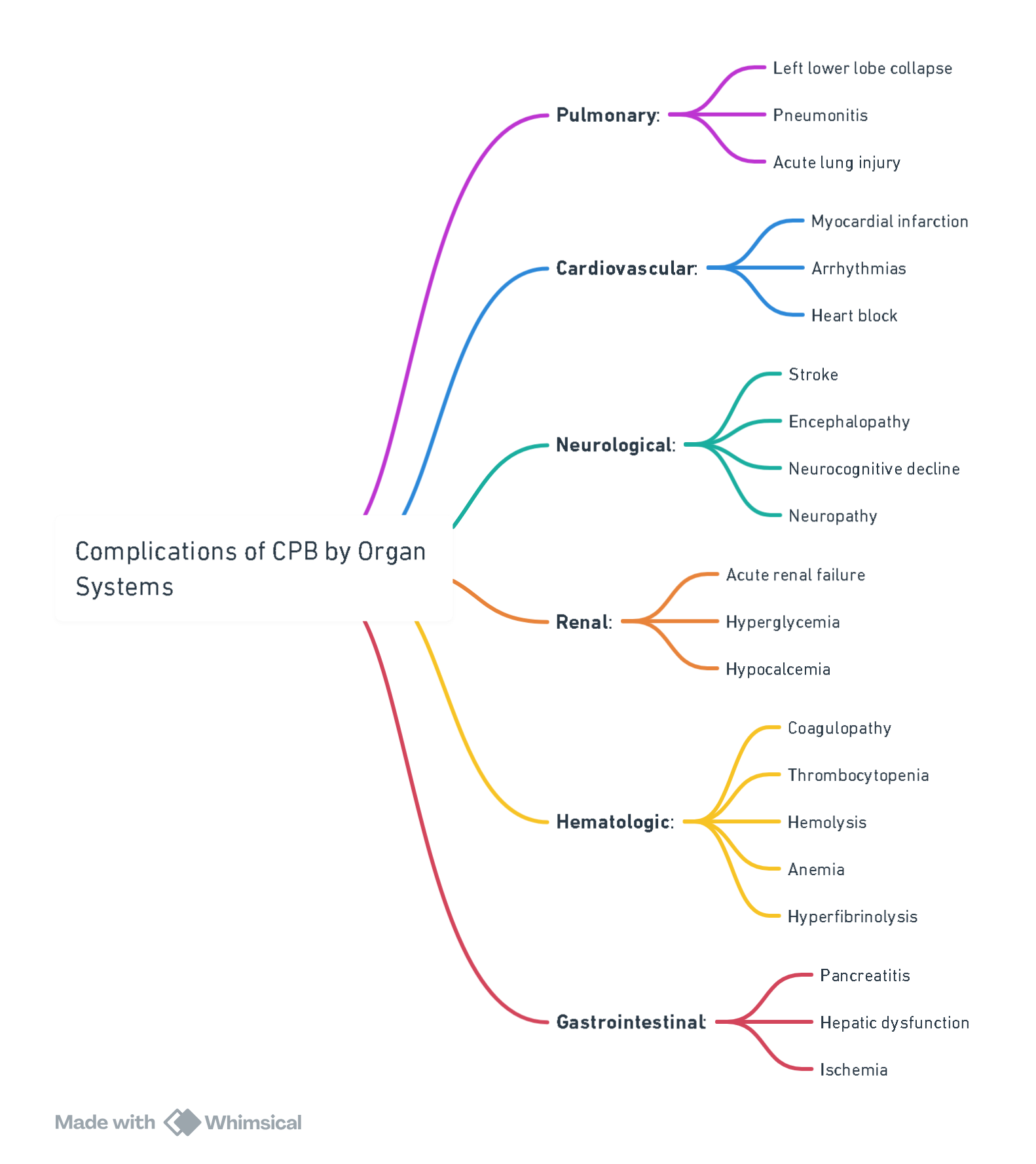

- Complications of CPB

- Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest (DHCA)

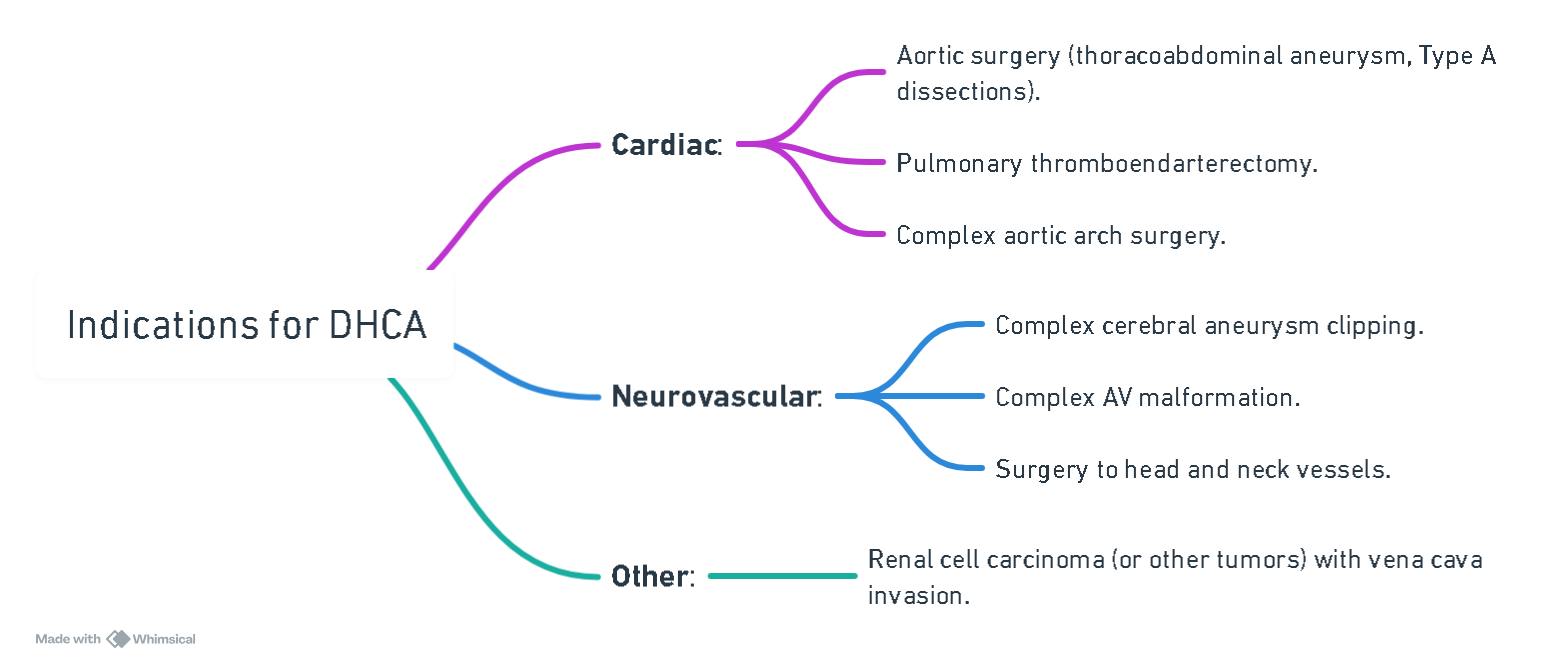

- Indications for DHCA

- Adverse Consequences of Hypothermia

- Process of DHCA

- Anesthesia for DHCA

- Cerebral Protection During DHCA

- Causes for Neurological Dysfunction after Bypass

- Measurement of Cerebral Temperature

- Acid–Base Management

- Hemodilution

- Glycemic Control

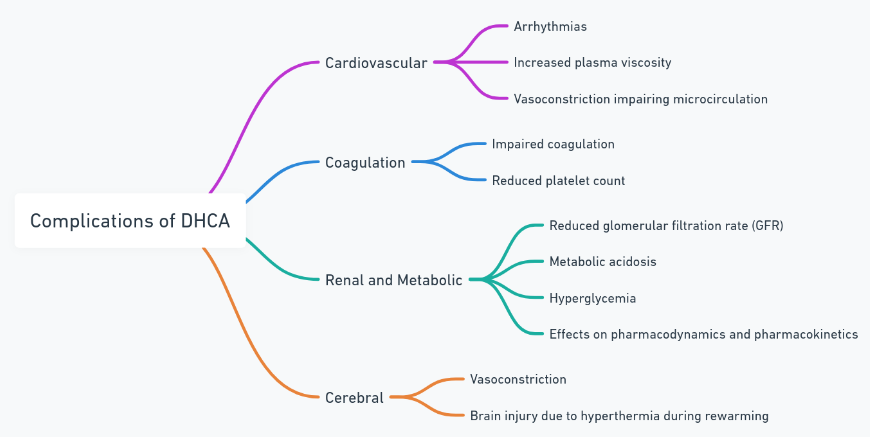

- Complications of DHCA

- Modifications to Standard Extracorporeal Circuit for DHCA

- High Vs Low MAP

- Temperature Options for Cardioplegia

- Surgical Techniques

- Postoperative Management

- Fetal Protection during CPB

- Links

{}

Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB)

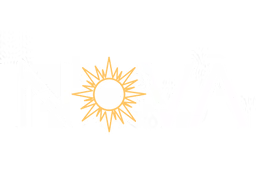

Components and Function

4 Functions

- Oxygenation and carbon dioxide elimination

- Circulation of blood

- Systemic cooling and warming

- Diversion of blood from the heart to provide optimal surgical conditions

Process

- Venous blood is drained by gravity into a reservoir that serves as a mixing chamber for blood, additional fluids, and drugs.

- Venous return to the reservoir can be altered by manipulating the hydrostatic pressure gradient between the heart and reservoir, enhanced by the application of negative pressure, or altered by adjusting the resistance to flow (e.g., using a clamp to partially occlude the venous line to fill the heart during bypass).

- From the reservoir, blood is pumped to an oxygenator and heat exchanger unit before passing through an arterial filter and returning to the patient.

- Additional pumps and components are used to manage shed blood (sucker), decompress the heart (vent), and deliver cardioplegia.

Blood Tubing

- Connects CPB components.

- Made of medical-grade PVC. Modern PVC tubing has biocompatible surface coatings and may be heparin-bonded to reduce proinflammatory effects.

Venous Reservoir

- Positioned between the venous line and the arterial pump to empty blood from the heart during bypass.

- Open (hard shelled) reservoirs: Allow passive removal of air entrained via the venous line through air vents on the reservoir cover and vacuum-assisted venous drainage.

- Closed (collapsible plastic bag) reservoirs.

Arterial Pumps

- Roller Pumps:

- Occlude a point in the tubing and squeeze blood forward while drawing in fluid behind the occlusive pump.

- Generate high or low pressures.

- Blood flow is calculated using tubing stroke volume (dependent on tubing diameter) and pump rpm.

- Centrifugal Pumps:

- Generate flow by magnetically coupling the high-speed revolution of a motor in the CPB machine to plastic fins and channels inside a disposable cone.

- Flow rate is affected by changes in pump preload and afterload, measured by an ultrasonic flow meter on the arterial side of the circuit.

- Less traumatic to blood, produce fewer plastic emboli, and less likely to cause cavitation with microscopic bubbles.

- Roller pumps are still used for cardioplegia, vent, and shed blood circuits.

Heat Exchangers

- Function via a counter-current mechanism in which heated or cooled water circulates around a conducting material with good thermal properties that is in contact with the blood.

Oxygenators

- Oxygenation, carbon dioxide removal, and administration of volatile anesthetic agents.

- Membrane oxygenators have replaced bubble oxygenators due to less blood cell damage and reduced micro-embolization.

- Gas exchange occurs by passive diffusion gradients across the membrane.

- Oxygen tension is controlled by the FiO2, and carbon dioxide elimination by total gas flows.

Arterial Line Filter (ALF)

- 20 – 40 μm ALF is placed on the patient side of the oxygenator to remove particulate and gaseous microemboli from the blood. No CPB system removes all emboli.

Prime

- Priming volume for a conventional adult circuit is 1.5 – 2.5 liters. Mini extracorporeal circuits (MECC) have priming volumes as low as 400 mL.

- Crystalloid primes using solutions such as lactated Ringer’s solution ensure similar osmolarity and electrolyte composition to plasma.

- Colloids may be added to decrease postoperative edema, mannitol to promote diuresis, and heparin to ensure adequate anticoagulation. Blood may be added to prevent dilutional anemia.

Monitors and Safety Devices

- In-line filters and bubble traps

- Low-level sensor detectors on the venous reservoir to prevent pumping air into the patient’s arterial system.

- Line pressure monitors to detect arterial cannula obstruction or aortic dissection.

- Flow measurement devices.

- Continuous in-line monitoring of blood gases and K+ using optical fluorescence technology is gaining popularity despite increased cost.

- CPB consoles have an emergency manual crank handle pump and battery backup in case of electricity supply failure.

Partial Bypass

- Some procedures, including surgeries involving the thoracic aorta, are performed using partial bypass, which is a technique that removes a portion of oxygenated blood from the left side of the heart and returns it to the femoral artery.

- Partial bypass allows for perfusion of the head and upper extremity vessels via the beating heart, and distal perfusion below the level of the aortic cross-clamp via retrograde flow by the femoral artery.

- Because all blood passes through the lungs, an oxygenator is not required

Harm from CPB

- Unphysiological due to hemodilution, non-pulsatile flow, hypothermia, alterations of blood viscosity, and lower than normal blood pressures.

- Exposure to CPB circuitry and cardiotomy suction blood activates complement, platelets, neutrophils, and pro-inflammatory kinins, leading to systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), amplified by ischemia-reperfusion injury from reperfusion of ischemic tissues as the cross-clamp is released.

- Adverse outcomes:

- Mortality (<1%)

- CNS (Embolization, ischaemia, bleeding, inflammation, edema, hyperthermia, anesthetic toxicity)

- Short term (<1 month) neurocognitive dysfunction: 25%–80%

- Long-term cognitive dysfunction: 10%–40%

- Stroke (1-5%)

- Renal dysfunction: 7%-9%

- AKI post bypass associated with 4-6 x increased short and long term mortality

- Hemodialysis: 1%-5%

- Pulmonary

- One of the earliest recognized complications of cardiac surgery using CPB. CPB has negative effects on the mechanical properties of the lungs (compliance and resistance) and the pulmonary capillary permeability. Increased permeability

- GIT (1-5%)

- Hyperbilirubinemia (3.7%), GI bleeding (1.2%), pancreatitis (0.8%), cholecystitis (0.3%), bowel perforation (0.1%), and bowel infarction (0.1%)

- Embolization:

- Cardiotomy suction blood contains fat, bone, lipids, and debris causing embolization leading to obstruction of microcapillary circulation, aggravation of inflammatory response, and organ dysfunction. The embolic load increases with longer bypass times.

- Gaseous emboli may be reduced by correcting air entrainment around venous cannulation sites, avoiding excessive vacuum-assisted venous drainage (> 20 mmHg), minimizing vent and cardiotomy suction flow, and using an arterial line and venous reservoir filter of < 40 μm.

- Cardiotomy suction blood contains fat, bone, lipids, and debris causing embolization leading to obstruction of microcapillary circulation, aggravation of inflammatory response, and organ dysfunction. The embolic load increases with longer bypass times.

Mitigation of Harm

Pharmacological

- Steroids, antiplatelet drugs, statins, TXA, etc., have no proven benefit.

Perfusion-related

- Biocompatible CPB circuits

- Leukocyte-depleting filters

- Pericardial blood processing

- Miniaturized CPB circuits

Benefits Observed in Studies

| No. of Studies (n = 14) | Result |

|---|---|

| 10 | Reduced hemodilution |

| 7 | Reduced transfusion requirements |

| 2 | Reduced fresh frozen plasma requirements |

| 3 | Reduced Intensive Care Stay |

| 3 | Reduced postoperative blood loss |

| 3 | Improved renal function |

| 4 | Better Cardiac Output Index |

| 6 | Reduced inflammation markers |

Managing Bypass

Optimal Flow

- Influenced by factors including patient’s BSA, temperature, acid-base management strategy, oxygen content of blood, metabolic rate, and specific organ ischemic tolerance.

- Flow rates are empirically determined based on BSA. Common adult flow rates during CPB: 2.2 – 2.5 L/min/m², although as low as 1.2 L/min/m² have been used during hypothermic bypass with good outcomes.

- Cerebral blood flow appears to remain relatively constant at flows of 1.0 – 2.4 L/min during hypothermic CPB.

Optimal Perfusion Pressure

- Optimal MAP and safe lower limit during bypass is unknown.

- Many institutions maintain a MAP of 50 – 60 mmHg during bypass, based on traditionally accepted cerebral autoregulation limits of 50 – 150 mmHg.

- High-risk groups for adverse neurological outcomes (elderly, hypertension, diabetes, advanced atherosclerotic disease of the aorta) should be managed with higher pressures (MAP=70) on bypass.

Temperature Management of Blood Gas Samples

- As body temperature decreases, the solubility of CO2 in blood increases, resulting in decreased PaCO2 and increased pH (unchanged total CO2 content).

- pH-stat hypothesis: Keeps pH constant at varying temperatures, requiring temperature correction of blood gas analysis to the patient’s actual body temperature.

- α-stat hypothesis: Maintains electrochemical neutrality at varying temperatures, primarily by protein buffering.

Optimal Hematocrit

- Hemodilution reduces blood viscosity and improves microcirculation but severe hemodilution may compromise oxygen delivery to tissues and decrease MAP.

- Hematocrits >17% are well tolerated.

Temperature

- CPB decreases overall body VO2 and is used to decrease whole-body oxygen demand and increase ischemic tolerance of organ systems.

- Hypothermia may adversely affect tissue oxygen delivery by increasing blood viscosity, reducing microcirculatory flow, and causing a leftward shift of the oxygen dissociation curve.

- Hypothermia is often absent during critical periods of potential brain injury (aortic cannulation, weaning from bypass).

- Numerous RCTs have compared warm vs cold temperature management during CPB, but most were underpowered to show differences in major morbidity and mortality.

Rewarming Considerations

- Temperature monitors do not always represent all organs.

- Highly perfused organs (brain, kidneys) can become hyperthermic.

- Too rapid rewarming is associated with neurological damage.

- Oxygen arterial outlet temperature should be used as a surrogate for cerebral temperature, maintaining < 37°C.

- Temperature gradient should be ≤ 10°C between the heater and venous blood to prevent microbubbles.

- Pulmonary artery or nasopharyngeal sites are acceptable when weaning from CPB and immediately thereafter.

Pulsatile Vs Non-pulsatile Flow

- Benefits of pulsatile flow on clinical outcomes are still uncertain due to the extra hydraulic energy needed to produce pulsatile flow.

Coagulation Monitoring

- Heparin is the gold standard anticoagulant for preventing clotting of blood on contact with the CPB circuit.

- Heparin acts as an antithrombin III agonist, accelerating AT III binding to thrombin.

- The Activated Coagulation Time (ACT) is the most widely used monitor of adequacy of heparinization in cardiac surgery.

- Normal ACT values range from 80-120 seconds.

- Factors altering ACT values include aprotinin, hypothermia, hemodilution, thrombocytopenia, and platelet inhibitor drugs.

Anticoagulation Management for Adults Undergoing CPB

Importance of Anticoagulation

- Prevention of Thrombus Formation: Anticoagulation is essential during CPB to prevent the formation of thrombi within the CPB circuit, which could otherwise lead to acute disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- Common Anticoagulant: Unfractionated heparin is the most commonly used anticoagulant for patients undergoing CPB.

Heparin Characteristics and Mechanism of Action

-

Molecular Properties:

- Structure: Heparin is a large, sulfated glycosaminoglycan polymer.

- Charge: It is negatively charged at physiological pH, which, along with its large size, keeps it primarily within the intravascular space.

-

Pharmacokinetics:

- Onset of Action: Heparin’s peak onset occurs approximately 1–3 minutes after intravenous administration.

- Elimination Half-Life: The half-life of heparin is about 1–1.5 hours.

- Excretion and Metabolism: Heparin is excreted through the kidneys and metabolized by the reticuloendothelial system.

-

Anticoagulant Mechanism:

- Heparin exerts its anticoagulant effects by binding to antithrombin III via a specific pentasaccharide sequence.

- This binding enhances the inhibitory action of antithrombin III, primarily against thrombin (factor IIa) and factor Xa, and to a lesser extent, against factors IXa, XIa, and XIIa.

- The result is the disruption of both the intrinsic and common pathways of plasma coagulation.

Heparin Dosing for CPB

-

Weight-Based Dosing:

- Common dosing for heparin is 300–400 U/kg in preparation for CPB.

- In morbidly obese patients, initial dosing may be based on ideal body weight, with additional heparin administered as needed.

-

Dose-Response Titration:

- ACT Measurement: The dose-response method involves measuring the activated clotting time (ACT) before and after a specific heparin dose (e.g., 200 U/kg).

- A dose-response curve is then generated by plotting these ACT values, allowing for extrapolation to determine the heparin dose required to achieve the target ACT.

-

CPB Priming Solution:

- The CPB priming solution should contain heparin at a concentration similar to that in the patient’s bloodstream to avoid dilution and maintain adequate anticoagulation.

- Typically, 5000–10,000 units of heparin are added to 1500 mL of the CPB priming solution to achieve a concentration of 3–4 units/mL.

Heparin Dose for CPB (Summary)

- Arterial blood sample for baseline ACT.

- Administer 300–400 IU/kg of unfractionated heparin via central venous catheter.

- Arterial blood sample for ACT after 3–5 minutes.

- Ensure ACT is 3–4 times baseline ACT (>480 s) before initiating CPB.

- 5000 IU unfractionated heparin in CPB prime solution.

- Monitor ACT at least every 30 minutes during CPB.

- Maintain ACT between 400–480 s during hypothermia (24–30°C) while on CPB.

- Reverse heparin with protamine after separation from CPB. Dose ratio 1 mg protamine per 100 IU of heparin, based on pre-CPB heparin dose.

- Arterial blood sample for ACT after 3–5 minutes.

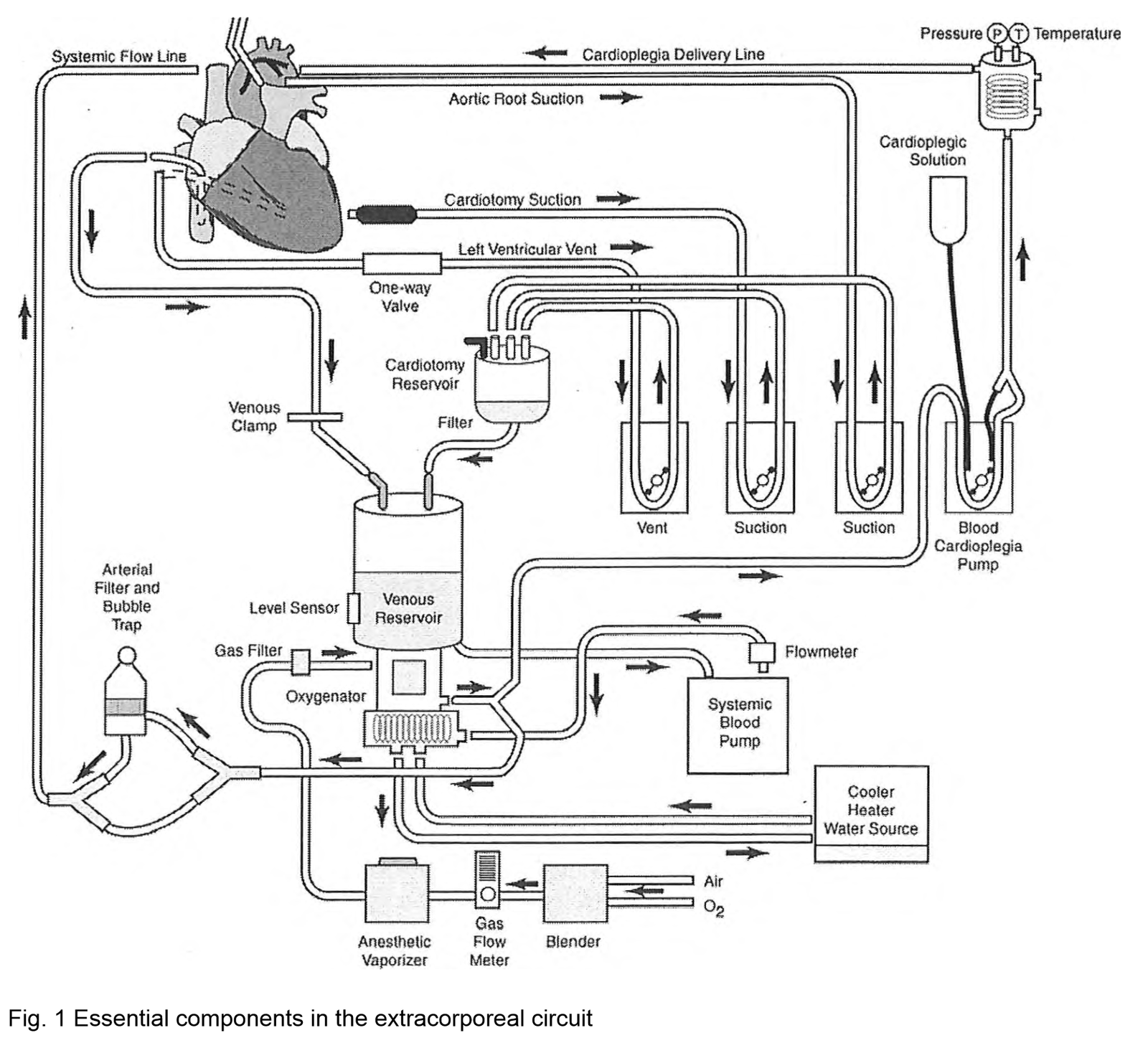

Resistance to Heparin

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Management of Heparin Resistance

Conditions Requiring Preoperative AT Level Draw

- Decreased synthesis (liver disease, malnutrition)

- Increased consumption (DIC, sepsis, DVT/PE)

- Increased loss (nephrotic syndrome)

- Mechanical support (ECMO, IABP, VAD)

- Heparin pre-treatment >48 hrs

- Decreased heparin responsiveness (in vitro HDR curve)

Protamine

Protamine Administration

- Initial Test Dose: Administer an initial test dose of protamine (10–20 mg) over 60 seconds.

- Full Neutralizing Dose: After the test dose, administer the full neutralizing dose of protamine slowly over 10 minutes.

- ACT Monitoring: Assess the adequacy of heparin reversal by checking the activated clotting time (ACT) 3–5 minutes after protamine administration. Additional protamine may be needed if ACT remains elevated.

Heparin Rebound and Additional Protamine Doses

- Heparin Rebound: Heparin may be released from plasma proteins or endothelial cells after the initial neutralization, leading to a subsequent rise in ACT, known as “heparin rebound.”

- Management: Administer an additional dose of protamine (30–50 mg) if heparin rebound occurs to bring ACT back to baseline.

- Heparinized Blood Transfusion: When heparinized blood is given after protamine has been administered, ACT may rise because protamine does not remain in the bloodstream for long.

- Management: A small bolus of protamine (1–2 mg per 20 mL of heparinized blood) should provide adequate neutralization.

Adverse Reactions to Protamine

-

Types of Reactions: Protamine can cause adverse effects, especially if administered too quickly. These reactions can be classified as anaphylactoid or anaphylactic and include:

- Hypotension: The most common adverse effect, caused by vasodilation, pulmonary hypertension, or myocardial depression.

- Management: Counteract vasodilation with vasoconstrictors and volume loading to stabilize blood pressure.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: Caused by protamine-induced release of thromboxane from pulmonary macrophages, leading to severe pulmonary vasoconstriction and potentially right and left heart failure.

- Management: Use inodilators in combination with vasoconstrictors for severe pulmonary hypertension and hypotension.

- Cardiac Depression: May require pharmacologic support depending on the severity.

- Hypotension: The most common adverse effect, caused by vasodilation, pulmonary hypertension, or myocardial depression.

-

Management of Protamine Reactions:

- Mild Cases: Generally self-limiting and may not require extensive intervention.

- Severe Cases: Severe reactions may necessitate a return to CPB. In such cases, re-anticoagulate with a full dose of heparin.

- Epinephrine: In cases of suspected anaphylactoid or anaphylactic reactions, small boluses of epinephrine may be beneficial, especially for managing refractory hypotension.

-

Special Precautions for Patients with Protamine Sensitivity:

- Test Dose: In patients with a history of protamine sensitivity, administer a very dilute test dose (1 mg in 100 mL over 10 minutes). If no adverse reaction occurs, the full dose of protamine should be administered slowly.

- Alternatives to Protamine: Currently, there are no recommended alternatives that can effectively reverse heparin post-CPB. Potential alternatives like platelet concentrates, synthetic polycations (e.g., hexadimethrine), methylene blue, and heparinase I have not proven sufficiently effective or safe.

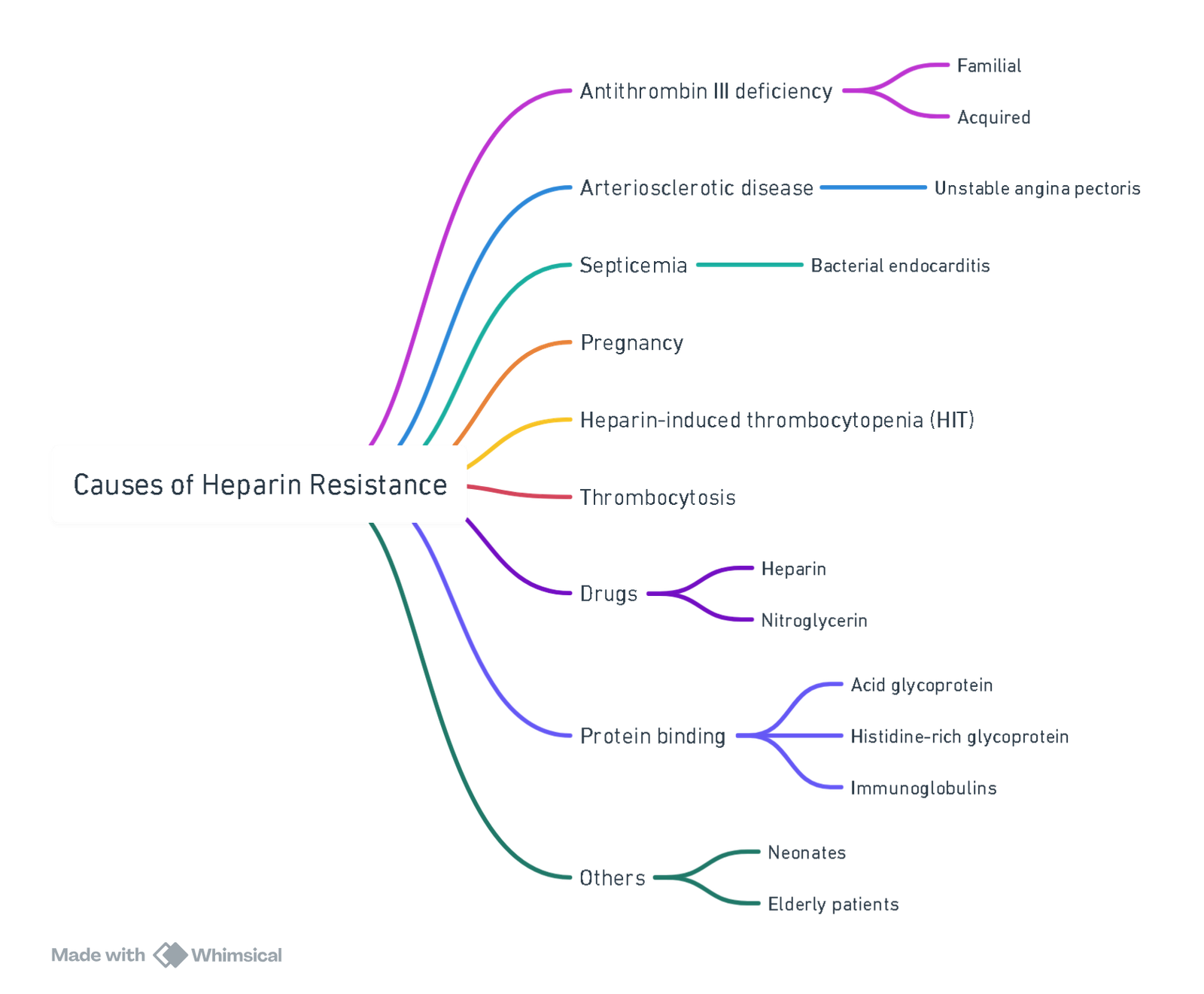

Complications of CPB

Abnormalities as a Result of Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB)

| Abnormality | Cause | Protective Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Thrombocytopenia | (1) Hemodilution (2) Sequestration (3) Consumption |

(1) Prime bypass circuit with blood (2) Use heparin-bonded circuits (3) Minimize bypass circuit size |

| Platelet Dysfunction | (1) Contact with bypass circuit (2) Hypothermia (3) Drugs (antiplatelet therapy preoperatively, heparin, protamine) (4) Fibrin degradation products |

(1) Use heparin-bonded circuits (2) Adequate rewarming post-CPB (3) Appropriate heparin and protamine dosing (4) Use antifibrinolytics (5) Minimize bypass circuit size |

| Coagulopathy | (1) Hemodilution (2) Consumption of coagulation factors |

(1) Retrograde prime of CPB circuit (2) Use heparin-bonded circuits (3) Conservative administration of intravenous fluids |

| Fibrinolysis | (1) Release of endothelial plasminogen activators (2) Activation of plasmin in response to fibrin formation |

(1) Use antifibrinolytics |

| Endothelial Cell Dysfunction | (1) Contact of blood with extracorporeal surfaces | (1) Use heparin-bonded circuits (2) Minimize CPB circuit size |

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Different Cardioplegia Solutions Considerations

Components

- Potassium (10–40 mEq/L) for arresting the heart in diastole, which is an easily reversible state

- Blood and/or crystalloid as the carrier

- Bicarbonate and/or THAM solution for buffering the excessive acid metabolites on bypass

- Mannitol to help reduce edema

- Magnesium to reduce calcium overload

- Citrate-phosphate-dextrose and amino acids such as glutamate and aspartate, for supplying any remaining metabolic demand of the heart which may only be present in the final “hot shot” which warms the heart and removes any remaining metabolites and cardioplegia.

- Blood vs Crystalloid:

- Potassium >20 mmol/L

- Blood: preserves myocyte and endothelial function (O2, nutrients, buffers, and scavenges free radicals).

- Warm vs Cold:

- Cold: 5-10°C ischaemic protection but increases reperfusion injury.

- Tepid: 27-30°C best overall protection and recovery.

- Warm: 37-38°C warm ischaemic injury if interrupted.

- Continuous vs Intermittent.

- Anterograde vs retrograde

- Anterograde: aortic root proximal to cross-clamp–quick arrest and good LVH protection. Need competent aortic valve.

- Retrograde: cannula into coronary sinus–need to vent aortic root. Insufficient for RV protection solely.

- Basic Principles:

- Potassium to arrest the heart.

- Slightly hyperosmolar to limit edema.

- Alkalotic to attenuate pH changes.

- Low Ca concentration to reduce reperfusion injury.

- Blood can be used for oxygen delivery, free radical scavenging, and buffering ability.

Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest (DHCA)

Indications for DHCA

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Adverse Consequences of Hypothermia

| Category | Consequences |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Arrhythmias, increased plasma viscosity |

| Coagulation | Impaired coagulation, reduced platelet count |

| Renal and Metabolic | Reduced glomerular filtration rate, metabolic acidosis |

| Cerebral | Vasoconstriction during cooling, brain injury during rewarming |

Process of DHCA

- Once CPB is established, patient is cooled to the desired temperature.

- Temperature gradient between CPB inflow and outflow line (nasopharyngeal temperature) is should be 5-8°C.

- Pack the head with ice to prevent passive rewarming.

- Pharmacological neuroprotective strategies (anaesthetic agents and NMBA) are administered before circulatory arrest.

- Once desired temperature (usually 18-20°C) is reached, patient is partly exsanguinated into CPB circuit and bypass is terminated.

- Blood is in stasis and no further drug can be infused nor blood can be sampled.

Anesthesia for DHCA

Premedication

- Consider corticosteroids as there is some evidence (albeit inconclusive) they are neuroprotective.

- Treat resultant hyperglycemia with insulin.

Temperature

- Temperature monitoring at two sites (nasopharynx and bladder) to estimate brain and body temperatures.

- Bladder and tympanic temperatures correlate most closely with brain temperature.

- Sites of Temperature Monitoring:

- Tympanic Membrane: Closest approximation to brain temperature.

- Nasopharynx: Commonly used to estimate brain temperature.

- Bladder: Commonly used to monitor core body temperature.

- Jugular Venous Bulb: Monitors jugular venous blood temperature, which is typically higher than brain temperature.

- Esophagus, Pulmonary Artery, Rectum: Less commonly used due to practical considerations, such as the presence of a TEE transducer which can make esophageal temperature monitoring less feasible.

- Temperature Differences:

- Nasopharyngeal and bladder temperature readings typically differ by 2°C–4°C.

- During rewarming, a bladder temperature above 34°C indicates adequate temperature restoration.

- Jugular Venous Temperature:

- Monitoring jugular venous temperature during rewarming can help confirm the absence of rebound cerebral hyperthermia, as it is usually higher than other sites, including the brain.

- CPB outflow temperature is the best indicator of jugular venous blood temperature.

Neuromonitoring

- Cerebral Substrate Delivery Monitors:

- Jugular bulb oximetry, transcranial Doppler sonography, and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS).

- Jugular venous oxygen saturation (SjO2) indicates the balance between cerebral oxygen supply and demand. Low SjO2 before DHCA is associated with adverse neurological outcome.

- NIRS measures oxygen saturation of blood in vessels to a depth of 20-40 mm.

- Cerebral Function Monitors:

- Quantitative electroencephalography (qEEG) and evoked potential monitoring.

- EEG becomes isoelectric at varying temperatures among patients.

| Parameter | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | – Silent EEG trigger to begin DHCA. – Detects epileptiform activity. – Sensitive indicator of POCD. |

– Cannot detect activity in deep regions. – Affected by ambient EM radiation and anesthetic drugs. – Technician needed. – Considerable individual variation at the temperature at which EEG goes silent. |

| Somatosensory Evoked Potentials (SSEP) | – Sensitive and specific in predicting postoperative neurological events. | – Affected by anesthetic drugs or EM interference. |

| Jugular Venous Bulb Oxygen Saturation (SjO2) | – Infers changes in cerebral metabolism indicating potential for neurological damage. – Measures cerebral temperature directly. |

– Global reading (not regional). – Does not correlate directly with EEG findings. |

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) | – Easy use. – Decreasing rSO2 = early indication of cerebral compromise. |

– Regional reading (not global). – Diathermy interferes with reading. |

Electroencephalography (EEG)

- Purpose: Continuous monitoring of cerebral electrical activity to predict cerebral injury.

- Use During DHCA: EEG is used to document burst suppression when brain temperature reaches 17°C, ensuring the brain is isoelectric for at least 3 minutes before circulatory arrest.

- Limitations: EEG is a sensitive but nonspecific monitor of cerebral blood flow (CBF), does not reflect neural activity in deep brain structures, and cannot determine the structural integrity of neurons.

Cerebral Oximetry

- Mechanism: Utilizes near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to measure regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rSO2) by transmitting light through the scalp and calculating rSO2 based on the absorption and reflection of light by oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin.

- Normal Values: The average rSO2 is about 55%–75%.

- Clinical Significance: A decrease in rSO2 below 55% for longer than 5 minutes is associated with a high risk of adverse neurologic outcomes.

- Limitations: Monitors only the frontal lobe, may be interfered with by electrocautery, and can give inaccurate readings due to abnormal hemoglobins, bilirubin levels, hypothermia, and alkalosis.

Jugular Venous Saturation (SjO2)

- Purpose: Reflects global cerebral oxygenation, with normal values between 65% and 75%.

- Clinical Significance:

- A decrease in SjO2 suggests reduced oxygen supply relative to demand, which could be due to hypotension or increased cerebrovascular resistance.

- An increase in SjO2 indicates low oxygen extraction, possibly due to reduced CMRO2 from hypothermia, pharmacologic agents, or severe brain injury.

- During Rewarming: An SjO2 less than 50% is associated with postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

Transcranial Doppler Ultrasound (TCD)

- Purpose: Measures velocity within the middle cerebral artery (MCA) as a surrogate for global cerebral blood flow.

- Use: Primarily used to detect emboli, which alter the Doppler signal sound.

Anticoagulation

- Unfractionated heparin (300-400iu/kg) to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) >400.q

- Tranexamic acid.

Cerebral Protection During DHCA

- Hypothermia

- Importance: Hypothermia is the most crucial component for brain protection during DHCA. It is classified as:

- Mild: 32°C–35°C

- Moderate: 26°C–31°C

- Deep: 20°C–25°C

- Profound: <20°C

- Effects on Cerebral Physiology:

- Decreases oxygen requirements and reduces cerebral blood flow linearly.

- Decreases the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) exponentially, with an average reduction of 6%–7% per 1°C decrease in temperature.

- At DHCA temperatures (15°C–22°C), electrical silence on electroencephalography (EEG) is often observed, with CMRO2 reduced to approximately 17%–20% of baseline.

- Mechanisms of Protection:

- Decreased formation of oxygen free radicals and glutamate.

- Reduced intracellular calcium influx.

- Increased production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

- Cooling Process:

- Cooling is initiated via cardiopulmonary bypass and should be performed slowly over at least 30 minutes to ensure even cooling and prevent a left shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve.

- Target core body temperature: 15°C–22°C.

- For patients with cerebrovascular disease, the head is packed in ice to promote cerebral hypothermia.

- Pharmacologic Protection

- Barbiturates:

- Used to reduce cerebral blood flow, CMRO2, seizure activity, and free radical formation.

- Common Agent: Sodium thiopental (10–20 mg/kg) titrated to burst suppression on the EEG.

- Disadvantages: Myocardial depression and delayed emergence.

- Propofol:

- Serves as a substitute for sodium thiopental and effectively induces electrical silence on EEG.

- No definitive evidence of neuroprotective effect.

- Steroids:

- High doses of methylprednisolone or dexamethasone decrease inflammatory cytokine release and prevent lysosomal breakdown, potentially reducing cerebral ischemia.

- Mannitol:

- An osmotic diuretic that may reduce cerebral and endothelial edema, scavenge free radicals, and decrease renal vascular resistance.

- Insulin:

- Tight blood glucose control (<180 mg/dL) with insulin infusion can minimize adverse neurologic outcomes by reducing tissue lactic acidosis.

- Nimodipine:

- A calcium channel blocker that reduces calcium influx into neurons, improving cognitive function post-CPB.

- Disadvantage: Higher incidence of hypotension.

- Dexmedetomidine:

- A selective α2 adrenergic receptor agonist that may protect against cerebral ischemia by inhibiting ischemia-induced norepinephrine release.

- Lidocaine:

- Reduces CMRO2 and improves short-term cognitive outcomes by selectively antagonizing voltage-gated sodium channels in neuronal membranes.

- Cerebral Perfusion Techniques

- Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass:

- Maintains some cerebral blood flow during DHCA, allowing for prolonged cooling periods.

- Selective Cerebral Perfusion (SCP):

- Allows for less profound hypothermia (22°C–25°C) without increasing ischemic risk.

- Antegrade Cerebral Perfusion (ACP):

- Involves selective hemispheric perfusion by placing a balloon-tipped arterial cannula in arteries such as the right axillary, subclavian, innominate, or common carotid artery.

- Flow rates: 10–20 mL/kg/min.

- Advantages: Provides near-physiologic perfusion, homogeneous blood flow distribution, global oxygenation, removal of ischemic metabolites, and control of cerebral temperature.

- Disadvantages: Risks include malperfusion, arterial dissection, embolization (plaque or air), displacement or kinking of the cannula, and reduced surgical exposure.

- Retrograde Cerebral Perfusion (RCP):

- Involves delivering cold oxygenated blood to the brain through a cannula in the superior vena cava (SVC).

- Flow rates: 300–500 mL/min to maintain SVC pressures <25 mm Hg.

- Advantages: Provides limited oxygenated blood to cerebral arteries (10%–20% of normal perfusion volume), maintains homogeneous cerebral hypothermia, and effectively flushes air, emboli, and ischemic metabolites.

- Disadvantages: Cerebral edema, intracranial hypertension, and insufficient oxygen delivery due to shunting. Recommended for patients at high embolic risk.

Causes for Neurological Dysfunction after Bypass

- Air and particulate embolism.

- Cerebral hypoperfusion.

- Ischemic reperfusion injury.

- Genetic predisposition.

- Exaggerated inflammatory response.

Measurement of Cerebral Temperature

- Directly: Jugular venous bulb (gold standard).

- Indirectly: Arterial inflow temperature, nasopharyngeal.

Acid–Base Management

- Solubility of gases in blood increases as temperature decreases.

- Corrected for body temperature, ABG analysis during hypothermia shows reduced PaO2, PaCO2, and alkalosis.

- Managed in two ways:

- Alpha-stat: Uncorrected (37°C). Maintains normal PaCO2 during mild-to-moderate hypothermia.

- pH-stat: Temperature-corrected to maintain normal pH. Increases cerebral oxygen delivery and improves global cerebral cooling. Recommended during cooling before DHCA.

Hemodilution

- Typically to a hematocrit of 20% to improve flow in microcirculation.

- Excessive hemodilution (<10%) significantly reduces oxygen-carrying capacity and causes tissue ischemia.

Glycemic Control

- Hyperglycemia during hypothermia worsens ischemia impact through increased glycolysis and intracellular acidosis.

- All patients undergoing DHCA require glucose control with insulin.

Complications of DHCA

Modifications to Standard Extracorporeal Circuit for DHCA

- Inline infusion bags for blood collection and storage during hemodilution.

- Centrifugal pump to reduce hemolysis.

- Hemofilter for hemofiltration.

- Leukocyte-depleting filter.

- Cardiotomy reservoir for volume during exsanguination.

- Arterio-venous bypass and accessory lines for retrograde/selective antegrade cerebral perfusion (SACP).

- Efficient heat exchanger.

- Consideration of heparin-bonded tubing.

High Vs Low MAP

- Lower MAP:

- Reduction in trauma to blood.

- Reduced bleeding in surgical field, reducing cardiotomy suction.

- Reduced embolic load to CNS.

- Higher MAP:

- Enhanced tissue perfusion associated with reduced risk of stroke.

Temperature Options for Cardioplegia

- Cold (5-10°C):

- Decreases metabolic requirement and aids in cardiac arrest but can worsen reperfusion injury.

- Tepid (27-30°C):

- Best overall protection and recovery.

- Warm (37°C):

- Restores energy stores quickly but requires continuous infusion which, if interrupted, can result in warm ischemic injury.

Goals of Cardioplegia

- Immediate and sustained electromechanical quiescence, maintenance of therapeutic additives in effective concentrations, and periodic washout of metabolic inhibitors.

- All cardioplegic solutions contain greater than physiologic levels of potassium, but they all vary in individual chemical constituents with respect to the addition of numerous additives.

Temperature of Cardioplegia Explanation

- Cold cardioplegia was felt early on to enhance myocardial preservation by reducing myocardial oxygen consumption, while warm cardioplegia better preserves myocardial cellular function and reduces the incidence of both postoperative low output syndrome and cardiac enzyme release (no statistical difference

Retrograde Vs Antegrade Cardioplegia

- Retrograde cardioplegia involves introducing the cardioplegia catheter into the coronary sinus, which allows for continuous cardioplegia administration.

- It is useful in situations in which antegrade cardioplegia is difficult to perform, including the presence of severe aortic insufficiency, severely diseased coronary arteries, or during aortic root/valve surgery. The ideal perfusion pressure to limit perivascular edema and hemorrhage is less than 40 mm Hg.

- Antegrade cardioplegia delivers the solution to the heart via the coronary ostia in the normal direction of blood flow (antegrade perfusion)

Surgical Techniques

- Retrograde Cerebral Perfusion (RCP) or Selective Antegrade Cerebral Perfusion (SACP) extends the safe duration of DHCA.

- Both techniques increase surgery complexity but allow lesser degrees of systemic hypothermia (22–25°C) without compromising safety.

Advantages and Disadvantages of RCP and SACP during DHCA

| RCP (Retrograde Cerebral Perfusion) | SACP (Selective Antegrade Cerebral Perfusion) |

|---|---|

| Advantages | Advantages |

| Helps maintain cerebral cooling | Prolongs safe length of DHCA more than RCP |

| Prolongs safe length of DHCA | Less hypothermia required |

| More reliable global oxygenation than RCP | |

| Disadvantages | Disadvantages |

| Variable oxygen delivery due to shunt | Risk of embolization |

| Cerebral edema | Increased surgery complexity |

| Raised ICP | Risk of cannula displacement |

RCP

- Cold oxygenated blood is directed into the snared superior vena cava (SVC) via an arterio-venous CPB shunt.

- Flow rates of 200–500 mL/min at a pressure of no greater than 25 mmHg are recommended, although pressures up to 40 mmHg are safe and more effective.

SACP

- The right or both carotid arteries are perfused using techniques like balloon-tipped arterial cannulae placed directly in the proximal common carotid arteries, the left subclavian artery is clamped, and perfusion commenced at 10–20 mL/kg/min to maintain a right radial artery pressure of 50–70 mmHg.

Postoperative Management

- Temperature decreases despite active warming methods.

- Adults tend to have specific intellectual or motor deficits.

- Neonates may have seizures or choreoathetoid movements.

- Mortality rates: 8%-15%; stroke rates: 7%-11%.

- Predictors of stroke: increased age, longer DHCA duration, atheroma or thrombus in the aorta.

- Coagulopathic hemorrhage is a significant cause of morbidity and early death after DHCA. TEG can guide management.

Fetal Protection during CPB

- Left lateral tilt

- Maternal saturation >92%

- Maternal Hct >28%

- High flow rates (>2.5 L/min/m²)

- High perfusion pressure (>70 mmHg)

- Consider pulsatile flow

- Maintain normothermia or mild hypothermia

- Alpha stat pH management

- Minimize CPB time

- Fetal monitoring

- Tocolysis if necessary

- Consider balloon valvuloplasty to avoid bypass

Links

References:**

1. Barry, Aaron E. MD*; Chaney, Mark A. MD*; London, Martin J. MD†. Anesthetic Management During Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Systematic Review. Anesthesia & Analgesia 120(4):p 749-769, April 2015. | DOI: 10.1213/And.0000000000000612](https://journals.lww.com/anesthesia-analgesia/fulltext/2015/04000/anesthetic_management_during_cardiopulmonary.13.aspx

2. Sarah Conolly, Joseph E Arrowsmith, Andrew A Klein, Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, Volume 10, Issue 5, 2010, Pages 138-142, ISSN 1743-1816 (https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkq024)

3. FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

Summaries:

CPB

Coag during bypass

Cerebral effects of bypass

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “bcf75cae-eecf-4e28-9f09-c438691cb8ad”