- Blood Flow During Pregnancy

- Functions of the Placenta

- Stages of Labor

- Drugs Used During Delivery

{}

Blood Flow During Pregnancy

- At term, uterine blood flow represents about 10% of the cardiac output, or 600 to 700 mL/min (compared with 50 mL/min in the nonpregnant uterus). 80% of this flow goes to the placenta, and 20% to the myometrium.

- The placenta lacks autoregulation and remains maximally dilated, but it has both alpha and beta receptors.

- Uterine blood flow is not significantly affected by respiratory gas tensions, but extreme hypocapnia (PaCO2 < 20 mm Hg) can reduce it.

- Blood flow is directly proportional to the difference between uterine arterial and venous pressures and inversely proportional to uterine vascular resistance.

- Three major factors decrease uterine blood flow during pregnancy:

- Systemic hypotension

- Uterine vasoconstriction

- Uterine contractions

- Common causes of hypotension during pregnancy include aortocaval compression, hypovolemia, and sympathetic blockade following regional anesthesia.

Functions of the Placenta

- Respiratory gas exchange

- Nutrition

- Waste elimination

Placental Exchange Mechanisms

Diffusion

- Respiratory gases and small ions are transported by diffusion.

- Most anesthetic drugs, with molecular weights under 1000, readily diffuse across the placenta.

Osmotic and Hydrostatic Pressure (Bulk Flow)

- Water moves across the placenta by osmotic and hydrostatic pressures, entering the fetal circulation in greater quantities than any other substance.

Facilitated Diffusion

- Glucose enters the fetal circulation down the concentration gradient facilitated by a specific transporter molecule, without consuming energy.

Active Transport

- Amino acids, vitamin B12, fatty acids, and some ions (calcium and phosphate) utilize active transport mechanisms.

Vesicular Transport

- Large molecules, such as immunoglobulins, are transported by pinocytosis. Iron enters the fetal circulation in this way, facilitated by ferritin and transferrin.

Breaks in the Placental Membrane

- Breaks in the placental membrane can allow mixing of maternal and fetal blood, which can lead to Rh sensitization.

Respiratory Gas Exchange

- Fetal O2 consumption: 7 mL/min/kg.

- The normal fetus at term can survive 10 minutes or longer in a state of total oxygen deprivation, compared to the expected 2 minutes. Partial or complete oxygen deprivation can result from umbilical cord compression, umbilical cord prolapse, placental abruption, severe maternal hypoxemia, or hypotension.

- Compensatory fetal mechanisms include redistribution of blood flow to the brain, heart, placenta, and adrenal gland; decreased oxygen consumption; and anaerobic metabolism.

- Transfer of oxygen across the placenta is dependent on the ratio of maternal uterine blood flow to fetal umbilical blood flow.

- Normal fetal blood from the placenta has a PaO2 of only 30 to 35 mmHg.

Aiding Oxygen Transfer

- The fetal hemoglobin oxygen dissociation curve is shifted to the left, and the maternal curve is shifted to the right.

- Fetal hemoglobin concentration is usually 15 g/dL (compared to approximately 12 g/dL in the mother).

Aiding Removal of CO2

- Carbon dioxide readily diffuses across the placenta.

- Maternal hyperventilation increases the gradient for CO2 transfer from the fetus to the maternal circulation.

- Fetal hemoglobin has less affinity for CO2 than adult forms of hemoglobin.

Drug Transfer Across the Placenta

- Drug transfer is reflected by the ratio of fetal umbilical vein to maternal venous concentrations (UV/MV).

- Fetal tissue uptake is correlated with the ratio of fetal umbilical artery to umbilical vein concentrations (UA/UV).

- The fetal effects of drugs administered to parturients depend on multiple factors, including route of administration, dose, timing, and maturity of fetal organs. Most anesthetic drugs are unlikely to reach high levels in the fetus if given during labor (due to uterine contraction and low doses).

Inhalation Agents

- Freely cross the placenta. Generally, these agents produce little fetal depression when given in limited doses (<1 MAC).

Ketamine, Propofol, and Benzodiazepines (BZD)

- Cross readily with minimal fetal uptake due to metabolism by maternal organs. Midazolam, given as a single dose for maternal anxiolysis, has no measurable effect on the fetus.

Opioids

- Cross the placenta readily but have variable effects depending on type:

- Morphine: Newborns are sensitive to its sedative effects.

- Fentanyl: Minimal effect at doses <1 μg/kg unless given directly before delivery.

- Alfentanil: Minimal effects.

- Remifentanil: UA/UV ratio is about 30%, indicating rapid metabolism in the neonate.

Muscle Relaxants

- Highly ionized and do not cross the placenta.

Local Anesthetics

- Local anesthetics are weakly basic drugs primarily bound to α1-acid glycoprotein.

- Placental transfer depends on pKa, maternal and fetal pH, and protein binding degree.

- Fetal acidosis increases fetal-to-maternal drug ratios due to trapping of local anesthetics in the fetal circulation.

- Highly protein-bound agents (e.g., bupivacaine and ropivacaine) diffuse slowly across the placenta, resulting in lower fetal blood levels compared to lidocaine.

- Chloroprocaine has the least placental transfer due to rapid hydrolysis by plasma cholinesterase in the maternal circulation.

- Ephedrine, β-adrenergic blockers (e.g., labetalol and esmolol), vasodilators, phenothiazines, antihistamines (H1 and H2), and metoclopramide are transferred to the fetus.

- Atropine and scopolamine cross the placenta, but glycopyrrolate does not due to its quaternary ammonium (ionized) structure.

Drug Effects on Uterine Blood Flow

- A small induction dose of propofol can produce greater reductions in blood flow due to sympathoadrenal activation (light anesthesia).

- Ketamine at doses <1.5 mg/kg does not significantly alter uteroplacental blood flow.

- Etomidate likely has minimal effects.

- Volatile inhalational anesthetics decrease blood pressure and potentially uteroplacental blood flow; <1 MAC has minimal effect.

Stages of Labor

First Stage

- Onset of true labor and ends with complete cervical dilation.

- Slow latent phase (2-4 cm) followed by a faster active phase (4-10 cm).

- Duration: 8-12 hours in nulliparous patients and 5-8 hours in multiparous patients.

Second Stage

- Begins with full cervical dilation, characterized by fetal descent, and ends with complete delivery of the fetus.

- Duration: 15-120 minutes.

- Contractions occur 1.5-2 minutes apart and last 1-1.5 minutes.

Third Stage

- Extends from the birth of the baby to the delivery of the placenta.

- Duration: 15-30 minutes.

- Current evidence indicates that dilute combinations of local anesthetics (e.g., bupivacaine ≤0.125%) and opioids (e.g., fentanyl ≤5 μg/mL) for epidural or combined spinal–epidural (CSE) analgesia do not prolong labor. Higher concentrations of local anesthetics (e.g., bupivacaine 0.25%) for continuous epidural analgesia may prolong the second stage of labor by approximately 15-30 minutes.

Factors That Prolong Labor and Increase Likelihood of Caesarean Section

- Primigravida

- Prolonged labor

- High parenteral analgesic requirements

- Use of oxytocin

- Large baby

- Small pelvis

- Fetal malpresentation

Drugs Used During Delivery

Phenylephrine (PEP)

- Small doses (40 μg) may increase uterine blood flow by raising arterial blood pressure without causing uterine contraction.

Oxytocin

- Half-life: 3-5 minutes.

- Induction doses for labor: 0.5-8 mU/min.

- Complications: Fetal distress due to hyperstimulation, uterine tetany, and, less commonly, maternal water retention (antidiuretic effect). Rapid IV infusion can cause transient systemic hypotension and reflex tachycardia.

Ergot Alkaloids

- Intense and prolonged uterine contractions.

- Constricts vascular smooth muscle and can cause severe hypertension if given as an IV bolus. Usually administered as a single 0.2 mg dose intramuscularly or in a dilute IV infusion over 10 minutes.

Prostaglandins

- Carboprost tromethamine (Hemabate, prostaglandin F2α) stimulates uterine contractions. Initial dose: 0.25 mg intramuscularly, repeatable every 15-90 minutes up to a maximum of 2 mg. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, bronchoconstriction, and diarrhea. Contraindicated in patients with asthma. Prostaglandin E1 (Cytotec, rectal suppository) or E2 (Dinoprostone, vaginal suppository) has no bronchoconstricting effects.

Magnesium

- Administered as a 4-g IV loading dose over 20 minutes, followed by a 1-2 g/h infusion.

- Therapeutic serum levels: 6-8 mg/dL.

- Serious side effects include hypotension, heart block, muscle weakness, and sedation. Magnesium intensifies neuromuscular blockade from nondepolarizing agents.

Β2 Agonists

- Ritodrine and terbutaline inhibit uterine contractions and are used to treat premature labor.

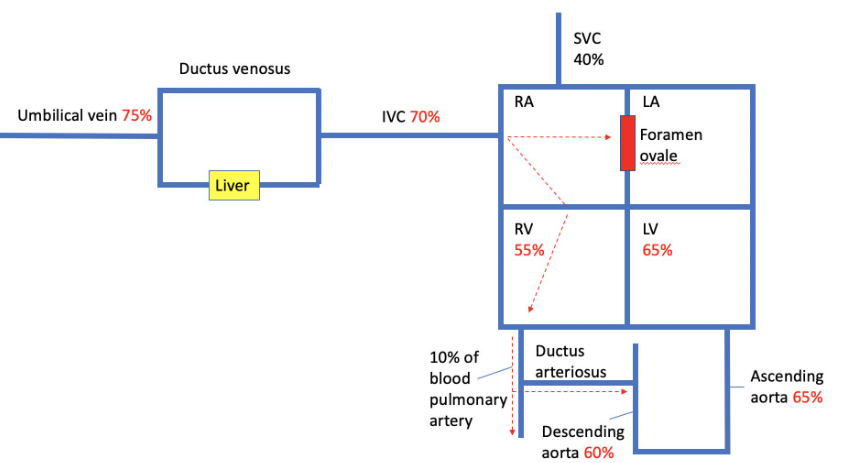

Fetal Circulation

Fetal Blood Flow

- Oxygenated Blood from Placenta: Well-oxygenated blood (approximately 80% oxygen saturation) from the placenta mixes with venous blood (25% oxygen saturation) returning from the lower body and flows via the inferior vena cava into the right atrium.

- Right Atrium to Left Atrium: Right atrial anatomy preferentially directs blood flow from the inferior vena cava (67% oxygen saturation) through the foramen ovale into the left atrium.

- Left Atrium to Upper Body: Blood from the left atrium is pumped by the left ventricle to the upper body, mainly the brain and the heart.

- Return from Upper Body: Poorly oxygenated blood from the upper body returns via the superior vena cava to the right atrium.

- Right Atrium to Right Ventricle: Right atrial anatomy preferentially directs flow from the superior vena cava into the right ventricle.

- Right Ventricle to Pulmonary Artery: Blood from the right ventricle is pumped into the pulmonary artery.

- Pulmonary Artery to Ductus Arteriosus: Due to high pulmonary vascular resistance, 95% of the blood (60% oxygen saturation) is shunted across the ductus arteriosus into the descending aorta, and back to the placenta and lower body.

Key Points

- Parallel Circulation: Results in unequal ventricular flows, with the right ventricle ejecting two-thirds of the combined ventricular outputs and the left ventricle ejecting one-third.

- Direct Bypass of Liver: 50% of the well-oxygenated blood in the umbilical vein can pass directly to the heart via the ductus venosus, bypassing the liver.

- Liver Passage: The remaining blood from the placenta mixes with blood from the portal vein and passes through the liver before reaching the heart, allowing rapid hepatic degradation of drugs or toxins absorbed from maternal circulation.

Physiological Changes During Birth

- At term, fetal lungs contain about 90 mL of a plasma ultrafiltrate.

Process During Birth

- Vaginal Squeeze: During delivery, this fluid is squeezed from the lungs by the pelvic muscles and vagina acting on the fetus. Remaining fluid is reabsorbed by pulmonary capillaries and lymphatics.

- Preterm/Cesarean Section: These neonates do not benefit from the vaginal squeeze and have greater difficulty maintaining respirations, leading to transient tachypnea of the newborn.

- Initiation of Respiratory Efforts: Within 30 seconds after birth, respiratory efforts begin, becoming sustained within 90 seconds. Mild hypoxia, acidosis, and sensory stimulation (cord clamping, pain, touch, noise) help initiate and sustain respirations, while the outward recoil of the chest aids in lung air filling.

- Lung Expansion: Increases both alveolar and arterial oxygen tensions, decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance.

- Pulmonary Arterial Vasodilation: The increase in oxygen tension is a potent stimulus for vasodilation.

- Closure of Foramen Ovale: Increased pulmonary blood flow and left atrial pressure functionally close the foramen ovale.

- Closure of Ductus Arteriosus: Increased arterial oxygen tension causes the ductus arteriosus to contract and functionally close. Chemical mediators such as acetylcholine, bradykinin, and prostaglandins also play a role.

- Establishment of Adult Circulation: Elimination of right-to-left shunting and the establishment of adult circulation. Anatomic closure of the ductus arteriosus occurs in about 2-3 weeks, while the closure of the foramen ovale takes months and may not occur at all.

Hypoxia and Acidosis

- During the first few days of life, hypoxia or acidosis can prevent or reverse physiological changes, leading to persistent fetal circulation or persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Right-to-left shunting promotes hypoxemia and acidosis, further increasing shunting, which can occur across the foramen ovale, the ductus arteriosus, or both.

Transitional Circulation

- Cord Clamp and Environmental Stimuli: Lungs expand to normal FRC, reduced PCO2, and increased PO2, reducing pulmonary vascular resistance and increasing pulmonary flow.

- Occlusion of Placental Circulation: Increased systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and blood pressure (BP), raising left atrial (LA) pressure and reducing pressure in the inferior vena cava (IVC) and right atrium (RA), leading to closure of the foramen ovale.

- Shunt Closure: Ductus venosus becomes the ligamentum teres. Ductus arteriosus constricts and shortens due to increased pO2 and reduced prostaglandins, leading to functional closure. Anatomical closure occurs through fibrosis over the next 4-6 weeks.

- Reversion: Secondary to hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis, inadequate depth of anesthesia, and pain can increase pulmonary pressures and reduce systemic pressures, leading to hypoxia and a reduction in BP.

CTG Monitoring

Guidelines for Fetal Monitoring

Pre-viability

- Fetal heart rate (HR) by Doppler before and after surgery.

Viable

- Minimum: Electronic fetal HR and contraction monitoring (CTG) pre and post-surgery.

Intraoperative Fetal Monitoring Criteria

- Viable fetus.

- Physically possible to monitor.

- Obstetrician available to intervene.

- Informed consent.

- Nature of surgery allows for safe interruption or alteration for emergency delivery.

- Tocometry can be used intraoperatively to guide tocolytic therapy or fluid boluses, particularly useful postoperatively when analgesia may mask early contractions.

Introduction

- Category I: Normal tracings.

- Category II: Indeterminate tracings that do not predict abnormal fetal acid-base status.

- Category III: Abnormal tracings include either absent baseline variability with recurrent late or variable decelerations, bradycardia, or the presence of a sinusoidal pattern, predicting abnormal fetal acid–base status.

Interpretation Acronym: DR C BRAVADO

- DR: Define risk.

- C: Contractions.

- BRa: Baseline rate.

- V: Variability.

- A: Accelerations.

- D: Decelerations.

- O: Overall impression.

Interpretation Parameters

- Heart Rate: 110 to 160 beats/min.

- Variability: Baseline beat-to-beat (R-wave to R-wave) variability: minimal (<5 beats/min), moderate (6–25 beats/min), or marked (>25 beats/min).

- Accelerations: Increases of 15 beats/min or more lasting for more than 15 seconds.

Cardiotocography (CTG) Interpretation

Reassuring

| Feature | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Baseline (beats/minute) | 110 to 160 |

| Baseline Variability (beats/minute) | 5 to 25 |

| Decelerations | None or early decelerations, Variable decelerations with no concerning characteristics* for less than 90 minutes |

Non-reassuring

| Feature | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Baseline (beats/minute) | 100 to 109† or 161 to 180 |

| Baseline Variability (beats/minute) | Less than 5 for 30 to 50 minutes or More than 25 for 15 to 25 minutes |

| Decelerations | Variable decelerations with no concerning characteristics for 90 minutes or more or Variable decelerations with any concerning characteristics in up to 50% of contractions for 30 minutes or Variable decelerations with any concerning characteristics* in over 50% of contractions for less than 30 minutes or Late decelerations in over 50% of contractions for less than 30 minutes, with no maternal or fetal clinical risk factors such as vaginal bleeding or significant meconium |

Abnormal

| Feature | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Baseline (beats/minute) | Below 100 or Above 180 |

| Baseline Variability (beats/minute) | Less than 5 for more than 50 minutes or More than 25 for more than 25 minutes or Sinusoidal |

| Decelerations | Variable decelerations with any concerning characteristics* in over 50% of contractions for 30 minutes (or less if any maternal or fetal clinical risk factors) or Late decelerations for 30 minutes (or less if any maternal or fetal clinical risk factors) or Acute bradycardia, or a single prolonged deceleration lasting 3 minutes or more |

Note: Concerning characteristics of variable decelerations include: lasting more than 60 seconds, reduced baseline variability within the deceleration, failure to return to baseline, biphasic (W) shape, and no shouldering.

† A baseline fetal heart rate between 100 and 109 beats/minute is non-reassuring only if there is normal baseline variability and no variable or late decelerations.

Decelerations

Early Decelerations (Type I)

- Characteristics: Usually 10–40 beats/min decrease.

- Cause: Vagal response to compression of the fetal head or stretching of the neck during uterine contractions.

- Pattern: Heart rate forms a smooth mirror image of the contraction.

Late Decelerations (Type II)

- Characteristics: Decrease in heart rate at or following the peak of uterine contractions, often subtle (as few as 5 beats/min).

- Cause: Placental insufficiency and fetal compromise, decreased arterial oxygen tension impacting atrial chemoreceptors.

- Significance:

- With normal variability: May follow acute insults (e.g., maternal hypotension or hypoxemia) and are usually reversible with treatment.

- With decreased variability: Associated with prolonged asphyxia and may indicate the need for fetal scalp sampling.

Variable Decelerations (Type III)

- Characteristics: Variable in onset, duration, and magnitude (often >30 beats/min), abrupt in onset.

- Cause: Cord compression and acute intermittent decreases in umbilical blood flow.

Fetoscopic Surgery

Anesthesia

- Remifentanil Infusion: Administer 0.1 mcg/kg/min to the mother.

- Direct Injections: Opioids, atropine, and neuromuscular blocking agents can be injected directly into the umbilical cord.

Links

- Paediatric anatomy and physiology

- Obstetric physiology

- Obstetric haemorrhage

- Obstetric emergencies

- Maternal conditions

Past Exam Questions

Circulatory Changes in the Transition from Fetus to Neonate

Describe the circulatory changes that occur in transition from fetus to neonate (10)

References:

- Allman K, Wilson I, O’Donnell A. Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia. Vol. 4. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Butterworth J, Mackey D, Wasnick J. Morgan and Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology, 7th Edition. 7th edition. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2022.

Summaries:

—

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “5c32fb89-ffb8-4df6-ad0d-f2e992802915”