{}

Summary

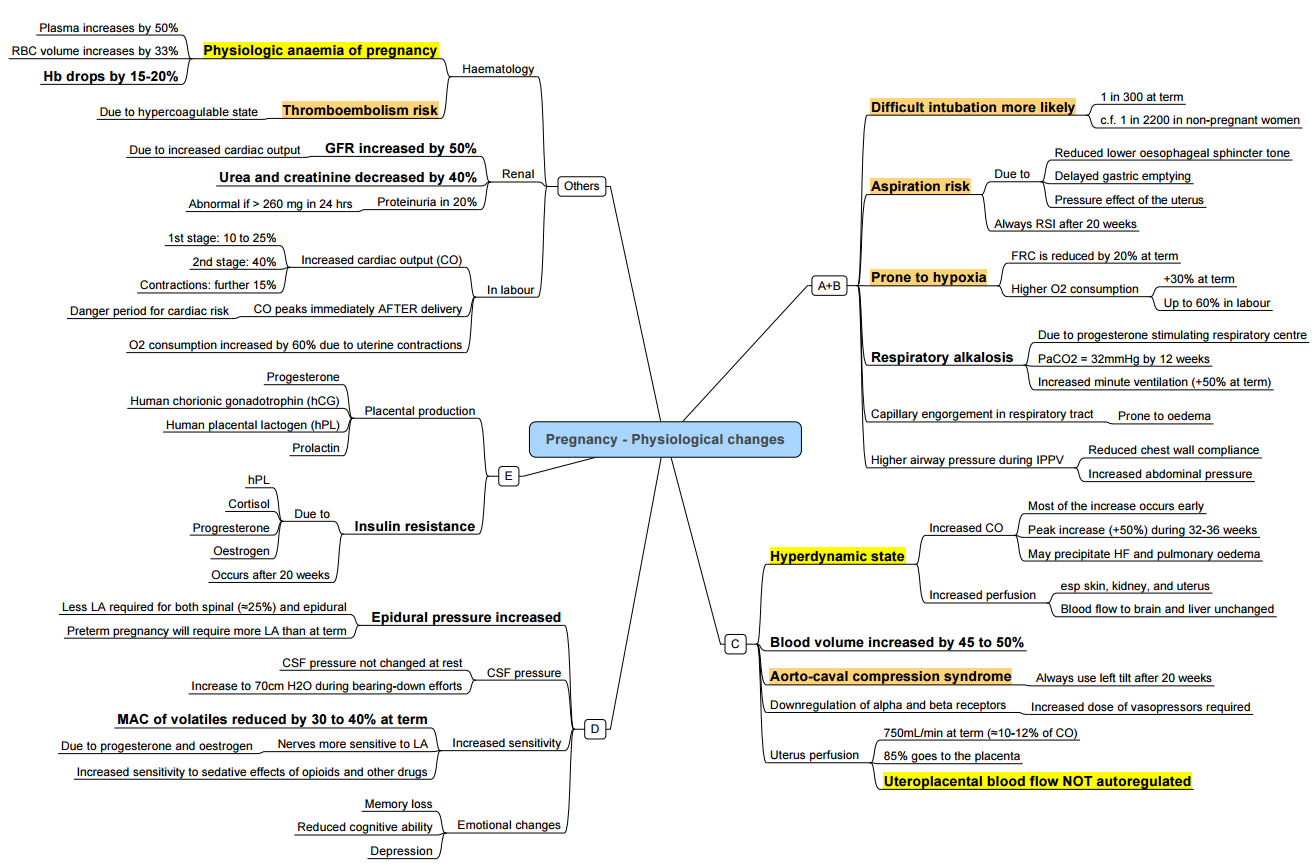

Physiological Changes in Pregnancy

Cardiovascular System (CVS)

- Intravascular volume increases by 35–45%; plasma volume by 40–50%; erythrocyte mass by 20–30%, resulting in physiological anaemia (haemodilution).

- Total blood volume reaches 90 mL/kg.

- Cardiac output ↑ 40–50% (↑ stroke volume 25–30%; ↑ heart rate 15–25%).

- Systemic vascular resistance ↓ ~20%; pulmonary vascular resistance ↓ ~35%.

- Central venous pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure remain unchanged; femoral venous pressure ↑ ~15%.

- Aortocaval compression: supine hypotension syndrome in 8–10% of women (↓ mean arterial pressure > 15 mmHg, ↑ heart rate > 20 bpm) due to gravid uterus compressing the inferior vena cava—left lateral tilt is recommended from mid-second trimester onwards.

- Electrocardiogram: slight rightward QRS axis shift in first trimester, leftward in third; minor ST-segment depression and T-wave flattening in lateral leads.

- Echocardiography: 10–20% enlargement of cardiac chambers (predominantly right heart), eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy, trivial regurgitation across atrioventricular valves, occasional small pericardial effusion.

Respiratory Changes

- Minute ventilation ↑ 40–50% (↑ tidal volume 40–45%; respiratory rate ↑ 5–15%), leading to respiratory alkalosis (arterial pH ~ 7.44, PaCO₂ ~ 30 mmHg, HCO₃⁻ ~ 20 mmol/L).

- Functional residual capacity ↓ 20%; expiratory reserve volume ↓ 20–25%; residual volume ↓ 15–20%, with minimal change in total lung capacity.

- Oxygen consumption ↑ 20–35% at term; further ↑ during labour (1st stage + 40%, 2nd stage + 75%).

- Airway mucosa is oedematous and hyperaemic, increasing risk of bleeding during instrumentation; breast enlargement and weight gain may complicate airway management.

Airway Changes

- Capillary engorgement increases risk for trauma and bleeding.

- Enlarged breast size can complicate laryngoscopy.

Neurological Changes

- MAC: Decreased 40% due to progesterone effects and beta-endorphin levels (sedative effect).

- Local Anaesthetics: Decrease dose by 30%. Hormonal effects and engorgement of the epidural venous plexus lead to decreased spinal cerebrospinal fluid volume, decreased epidural space volume, and increased epidural pressure.

Renal Changes

- Glomerular filtration rate ↑ ~ 50%, with corresponding ↓ serum creatinine (to ~ 0.4–0.6 mg/dL) and urea.

- Plasma osmolality ↓ by 8–10 mOsm/kg; thirst threshold lowered.

Coagulation Changes

- Haemoglobin concentration ↓ ~ 12–14 g/dL; white cell count ↑ up to 15 × 10⁹/L; platelet count may fall by 10–20%.

- Coagulation: ↑ fibrinogen (factor I), factors VII, VIII, IX, X, XII and von Willebrand factor; ↓ antithrombin III and protein S; net hypercoagulable state reduces bleeding risk but ↑ thromboembolism.

Gastrointestinal Changes

- Increased gastroesophageal reflux and esophagitis.

- Reduced gastric motility and incompetence of gastroesophageal sphincter due to uterine displacement.

- 30%-60% of pregnant patients have a gastric volume >25 mL or gastric fluid pH <2.5.

- High risk for regurgitation and pulmonary aspiration.

Hepatic Changes

- Decreased pseudocholinesterase by 30%.

- High progesterone levels inhibit cholecystokinin release, leading to incomplete gallbladder emptying and gallstones.

- Minor elevations in AST, ALT, ALP, and LDH.

- Plasma protein concentrations decrease: 25% decrease in albumin, 10% decrease in total protein at term.

- Colloid osmotic pressure decreases from 27 to 22 mmHg during gestation.

Metabolic Changes

- Diabetogenic state with increased insulin levels due to human placental lactogen leading to insulin resistance.

- Pancreatic beta cell hyperplasia in response to increased insulin demand.

- Elevated levels of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) due to increased thyroid-binding globulin; free T4, free T3, and TSH remain normal.

- Serum calcium levels decrease, but ionized calcium concentration remains normal.

Musculoskeletal Changes

- Increased relaxin leading to backache.

Endocrine Changes

- Placenta Produces:

- Progesterone

- Estrogen

- Prostaglandins

- Human placental lactogen (HPL)

- Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG)

- Pituitary:

- Increased ACTH and prolactin.

- RAAS Stimulation:

- Directly by estrogen.

- Indirectly by progesterone’s natriuretic effect reducing sodium and stimulating RAAS.

- Adrenals:

- Increased cortisol.

- Thyroid:

- Increased T3, T4, and thyroxine-binding globulin; normal unbound levels.

- Pancreas:

- Increased insulin secretion with reduced tissue sensitivity, leading to more glucose availability for the fetus.

Delivery

- Minute ventilation may increase up to 300%.

- Oxygen consumption increases by an additional 60% above third-trimester values.

- Excessive hyperventilation can cause PaCO2 to decrease below 20 mm Hg.

- Marked hypocapnia can lead to hypoventilation and transient maternal and fetal hypoxemia between contractions.

- Excessive hyperventilation reduces uterine blood flow and promotes fetal acidosis.

- Each contraction displaces 300-500 mL of blood from the uterus into the central circulation, increasing cardiac output by 45% over third-trimester values.

- The greatest cardiac strain occurs immediately after delivery, with cardiac output increasing up to 80% above late third-trimester values.

Return to Normal

- FRC: Returns to normal within 48 hours after delivery.

- Blood Volume: Normalizes within 1-2 weeks.

- Pseudocholinesterase Levels: Return to normal within 6 weeks.

- MAC: Returns to normal by 72 hours postpartum.

- Dosage Requirements for Regional Anesthesia: Return to normal within 24-36 hours.

- Gastric Volume and Fluid pH: Normalize within 24 hours after delivery.

- Some physiological changes may take up to 6 weeks for resolution.

- Cardiac Output: Decreases substantially toward prepregnant values by 2 weeks postpartum, with complete return to nonpregnant levels between 12 and 24 weeks postpartum.

Links

- Non obstetric surgery

- Fetus and Placenta

- Maternal conditions

- Obstetric haemorrhage

- Obstetric emergencies

References:

- Allman K, Wilson I, O’Donnell A. Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia. Vol. 4. Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2016. 1295 p. Allman et al. – Oxford Handbook of Anaesthesia.pdf

- Butterworth J, Mackey D, Wasnick J. Morgan and Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology, 7th Edition. 7th edition. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2022.

- Gropper, M. A. (Ed.). (2019). Miller’s Anesthesia (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

- Canobbio, M. M., Warnes, C. A., Aboulhosn, J., Connolly, H. M., Khanna, A., Koos, B. J., … & Stout, K. (2017). Management of pregnancy in patients with complex congenital heart disease: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association. Circulation, 135(8). https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000458

- Bhatia N, Riou B. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(3):475–486

- Leighton BL, Smith IP. Respiratory physiology in pregnancy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(3):345–350.

- Miller RD, Cohen NH, Eriksson LI, et al., editors. Miller’s Anesthesia. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2020.

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries

Obs physiology

—

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “ecb96c02-e36e-45ed-b40e-ff76851f02dd”