- Summary

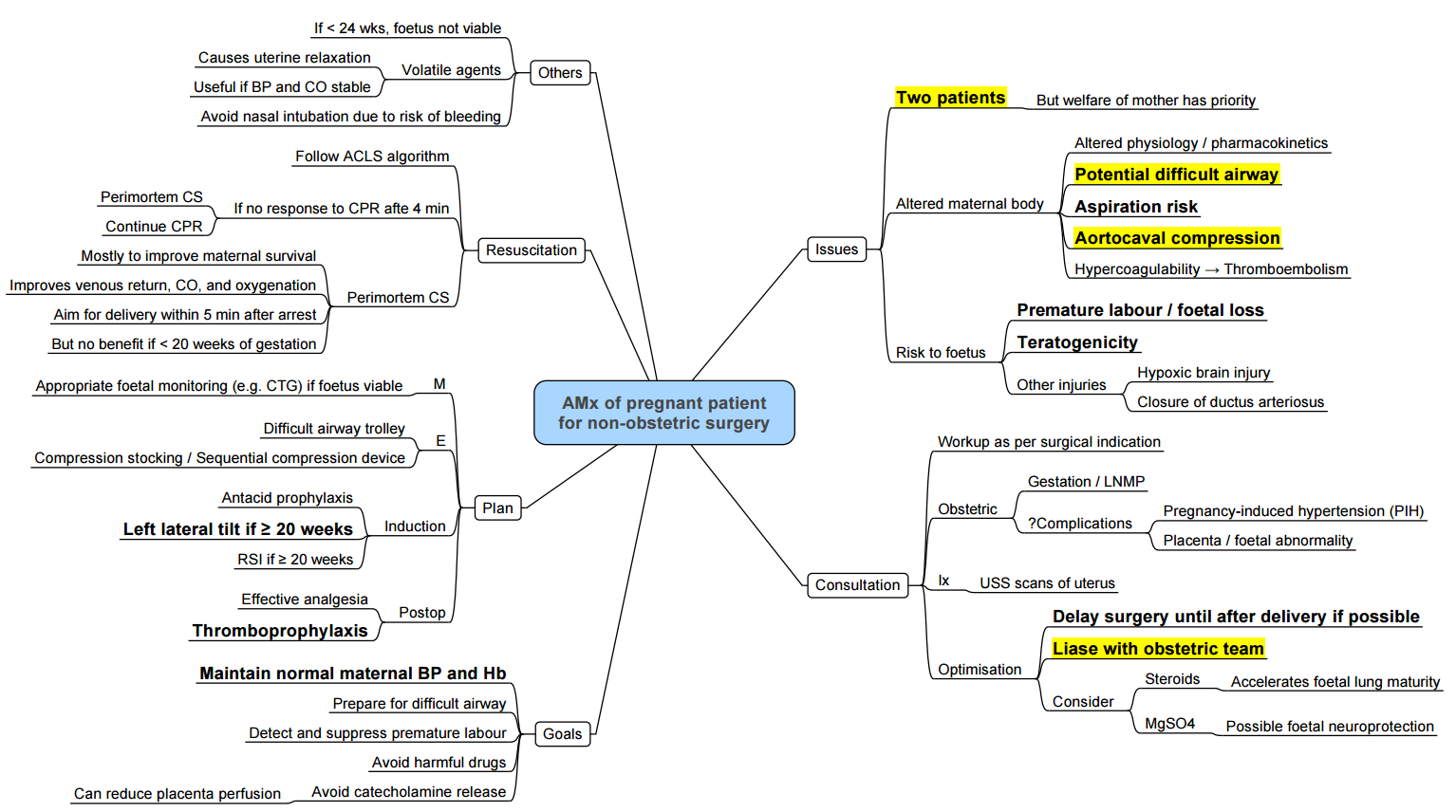

- Non-Obstetric Surgery in Pregnancy

- Conduct of Anaesthesia for Non-obstetric Surgery

- Key Considerations

{}

Summary

Non-Obstetric Surgery in Pregnancy

Anaesthetic and Obstetric Safety

- No anaesthetic agent used at clinical concentrations is proven teratogenic in humans; historic associations (e.g., diazepam and cleft lip) have been disproven

- FDA warning on anaesthetic neurotoxicity in animal models has not been confirmed in human observational studies or early childhood neurodevelopment follow‑up trials (e.g., GAS consortium)

- Urgent or emergent non-obstetric surgery should not be delayed regardless of trimester; elective procedures are preferably postponed until ≥ 6 weeks postpartum

- Multidisciplinary planning (anaesthesia, obstetrics, surgery, neonatology) and intraoperative fetal monitoring are recommended for viable pregnancies

Incidence and Timing

- First trimester: 42% of surgeries; risk of miscarriage greatest due to embryogenesis.

- Second trimester: 35%; lowest rate of obstetric complications, often considered safest window.

- Third trimester: 23%; increased risk of preterm labour and technical difficulty due to uterine size

Common Indications

- Acute abdominal pathology (appendicitis, cholecystitis, bowel obstruction)

- Maternal trauma (e.g., splenectomy, orthopaedic fixation)

- Oncological resections (e.g., breast, adnexal masses)

Anaesthetic Considerations

- Preoperative: Obstetric consultation, fetal viability assessment, uterotonic and tocolytic availability, thromboprophylaxis.

- Physiological changes: Increased cardiac output, decreased systemic vascular resistance, aortocaval compression—use left lateral tilt.

- Monitoring: Standard ASA monitors plus invasive blood pressure; consider fetal heart rate monitoring when ≥ 24 weeks.

- Airway: Anticipate difficult airway; apply obstetric GA modified RSI if general anaesthesia required.

- Positioning: Left uterine displacement with wedge or manual technique.

- Postoperative: Thromboprophylaxis, pain control with multimodal/regional techniques, obstetric observation for preterm labour.

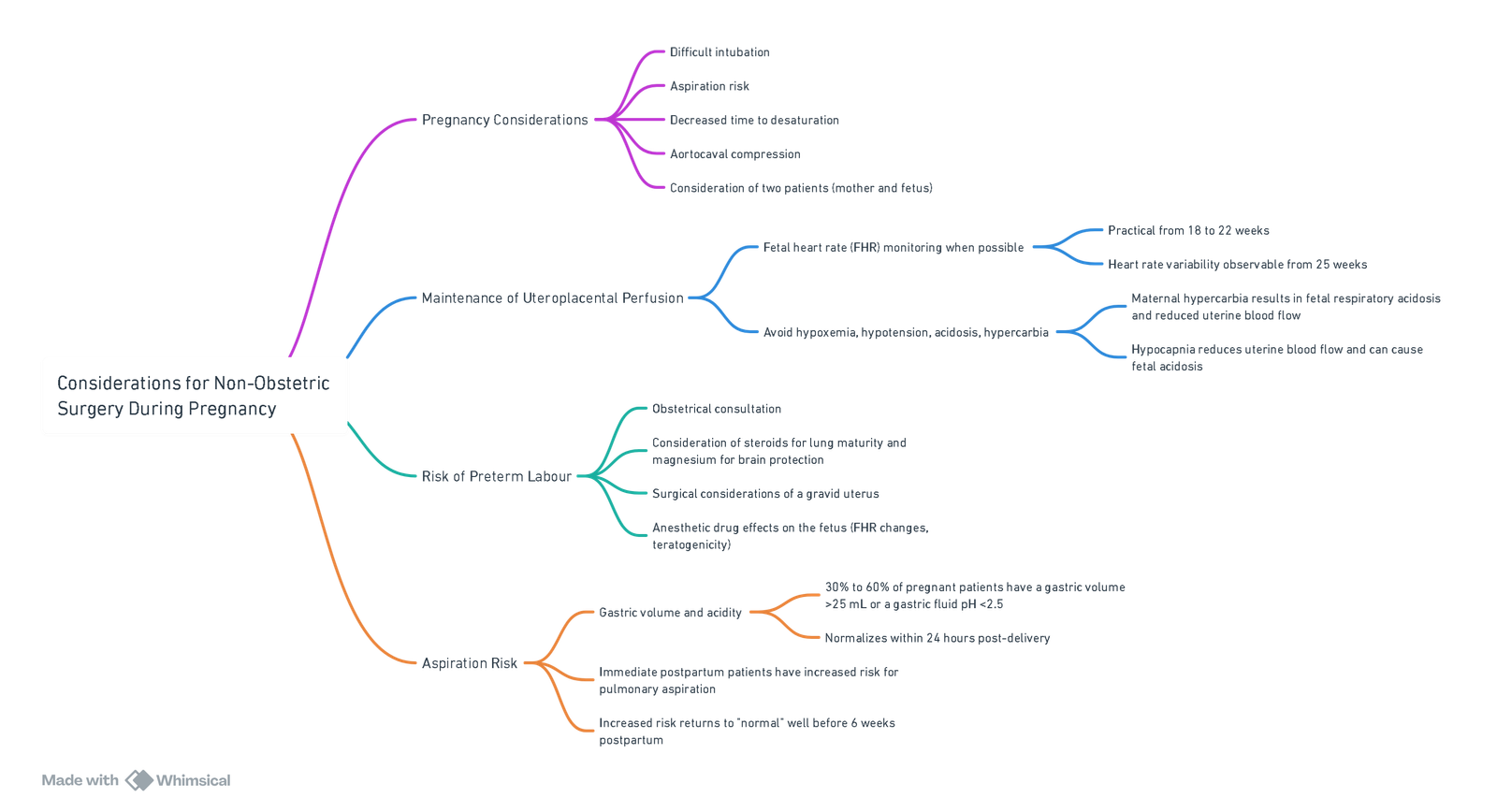

Considerations

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Anaesthetic Concerns in Maternal Care

Maternal Safety

- Physiological changes of pregnancy increase risks of hypoxia, hypotension and aspiration.

- Urgency of surgery and underlying maternal pathology (e.g., trauma, infection, malignancy) may complicate anaesthetic management.

Foetal Safety

- Placental transfer of anesthetic and adjunct drugs must be considered.

- Teratogenicity depends on timing (all-or-nothing period vs organogenesis vs functional development), dose and duration of exposure.

- Maternal factors risking fetal compromise include:

- Hypoxaemia

- Hypocarbia or hypercarbia

- Reduced uteroplacental blood flow from hypotension or aortocaval compression

Foetal Monitoring

- Doppler heart rate measurement: Single assessments preand post-procedure for previable fetuses.

- Electronic fetal heart rate and contraction monitoring: Continuous before and after surgery for viable fetuses.

- Intraoperative monitoring: Consider in viable fetuses if interventions (maternal repositioning, oxygen therapy, vasopressors) will be guided by tracings; requires trained interpreter and readiness for emergency Caesarean delivery.

Goals and Conflicts

- Delay non-elective procedures until the second trimester when feasible.

- Maintain maternal oxygenation, normocapnia and hemodynamic stability.

- Optimise uteroplacental perfusion; if fetal monitoring is actionable, tailor interventions accordingly.

Preparations for Preterm Labour

- Assess and discuss fetal lung maturity and tocolysis strategies.

- Ensure neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) availability.

- Minimise uterine stimulation by using regional analgesia and avoiding uterotonic agents unless clinically indicated.

General Anaesthesia (GA) Considerations

- Pulmonary aspiration: Perform modified RSI; extubate awake when reflexes return; utilise fasting guidelines and pharmacological prophylaxis (H₂ blockers, antacids, metoclopramide).

- Anaemia: Haemoglobin ≥ 7 g·dL⁻¹ acceptable in stable patients; transfuse based on clinical context.

- Plasma cholinesterase reduction: Prolonged succinylcholine action may necessitate alternative neuromuscular blocking agents.

- Volatile agents: Use ≤ 0.5–1.0 MAC to minimise uterine relaxation and blood loss.

- Intravenous opioids: Fentanyl and remifentanil preferred for minimal neonatal depression; avoid meperidine and high-dose morphine near delivery.

- Post‑anaesthetic breastfeeding: Early feeding encouraged; routine “pump and dump” outdated.

Key Points

- Prevent maternal hypoxaemia, hypotension and acidosis.

- Ensure gentle pre-oxygenation and normoventilation during GA.

- Position with 15°–30° left lateral tilt from 20 weeks’ gestation.

- Use safe drug profiles: propofol, ketamine (subanaesthetic doses), rocuronium, local anaesthetics. Avoid nitrous oxide and benzodiazepines where possible.

- Foetal monitoring intraoperatively only when results will drive management; be prepared for tocolysis if contractions occur.

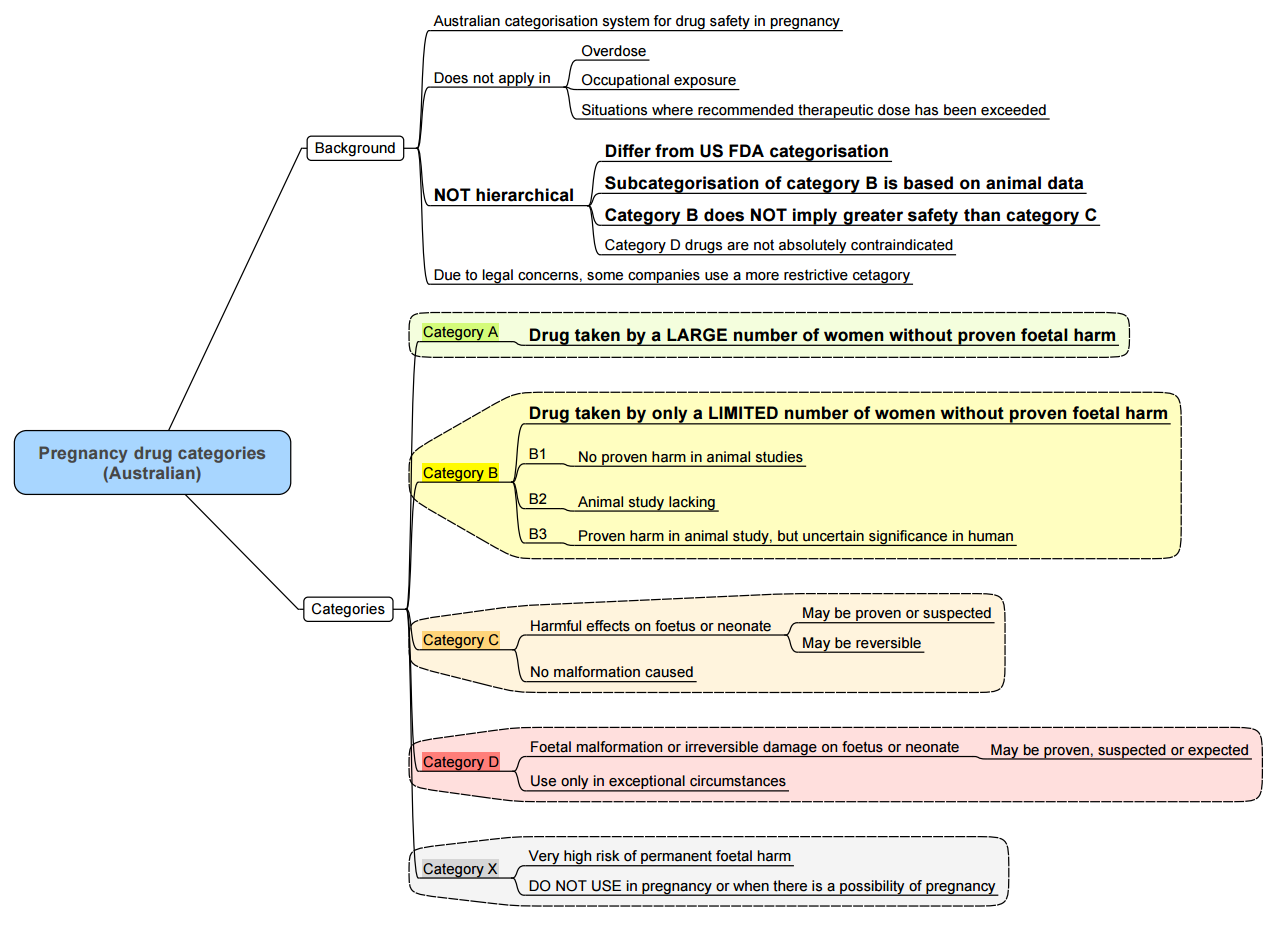

Pharmacological Considerations

Physiological Changes

- Increased total body water → ↑ volume of distribution for hydrophilic drugs.

- Increased adipose tissue → ↑ distribution of lipophilic agents.

- ↓ Plasma albumin → ↑ free fraction of protein-bound drugs.

- ↑ Cardiac output → ↑ hepatic and renal clearance.

Drug Effects

- Volatile agents: Decrease uterine tone; choose lowest effective concentration.

- Propofol: Reduces uterine blood flow at high doses; antiemetic properties.

- Ketamine: Maintains blood pressure; avoid boluses in early gestation due to uterine tone.

- Opioids: Cross placenta; use remifentanil infusion for rapid offset if needed.

- Heparin: Does not cross placenta; preferred anticoagulant for thromboprophylaxis.

Teratogens

Effects and Risks

- Teratogenic potential highest during organogenesis (weeks 3–8).

- “All‑or‑nothing” effects in first 2 weeks post‑conception.

- Later exposures may cause functional deficits rather than structural anomalies.

Nitrous Oxide

- Inactivates methionine synthase; animal studies show teratogenicity at high concentrations and durations not used clinically.

- Limit use in the first trimester; avoid prolonged high-flow administration.

Common Non‑Anaesthetic Teratogens

- ACE inhibitors 2. Alcohol 3. Androgens 4. Antithyroid drugs 5. Carbamazepine 6. Chemotherapy 7. Cocaine 8. Warfarin 9. Valproic acid 10. Lithium 11. Phenytoin 12. Streptomycin 13. Tetracyclines 14. Thalidomide 15. Trimethadione 16. Diethylstilbestrol

Obstetric Drug Safety

Placental Transfer Factors

- Placental metabolism──enzyme activity modulates fetal exposure.

- Transporters──P-gp and other efflux pumps.

- pH differences──ion trapping may occur for weak acids/bases.

- Surface area and thickness──anatomic factors.

- Uteroplacental blood flow──drives passive diffusion.

Drug Characteristics

- Concentration gradient 2. Lipid solubility 3. Molecular weight (<500 Da crosses readily) 4. pKa and ionisation 5. Protein binding

Classification of Placental Drug Transfer

Summary of Pharmacologic Agents and Maternal–Fetal Considerations

Benzodiazepines

- Category D historically; recent data show limited teratogenic risk.

- Avoid in first trimester; minimise near delivery to prevent neonatal sedation.

Opioids

- Therapeutic doses safe; high-dose or prolonged use associated with neonatal abstinence syndrome.

- Breastfeeding supported in stable methadone or buprenorphine therapy.

NSAIDs

- Avoid after 32 weeks due to ductus arteriosus constriction and renal effects.

- Use acetaminophen as first-line analgesic.

Local Anaesthetics

- Lidocaine with adrenaline preferred; monitor for systemic toxicity.

- Bupivacaine toxicity risk ↑ due to reduced α1‑acid glycoprotein.

Muscle Relaxants & Reversal

- Succinylcholine and rocuronium safe; sugammadex use limited data.

Inhalational Agents

- Sevoflurane and desflurane safe; maintain ≤1 MAC.

- Nitrous oxide reserved; avoid prolonged administration.

IV Induction Agents

- Propofol first-line; thiopental less commonly used.

- Ketamine for hemodynamic instability; use judiciously.

Antiemetics

- Ondansetron safe; dexamethasone considered after first trimester.

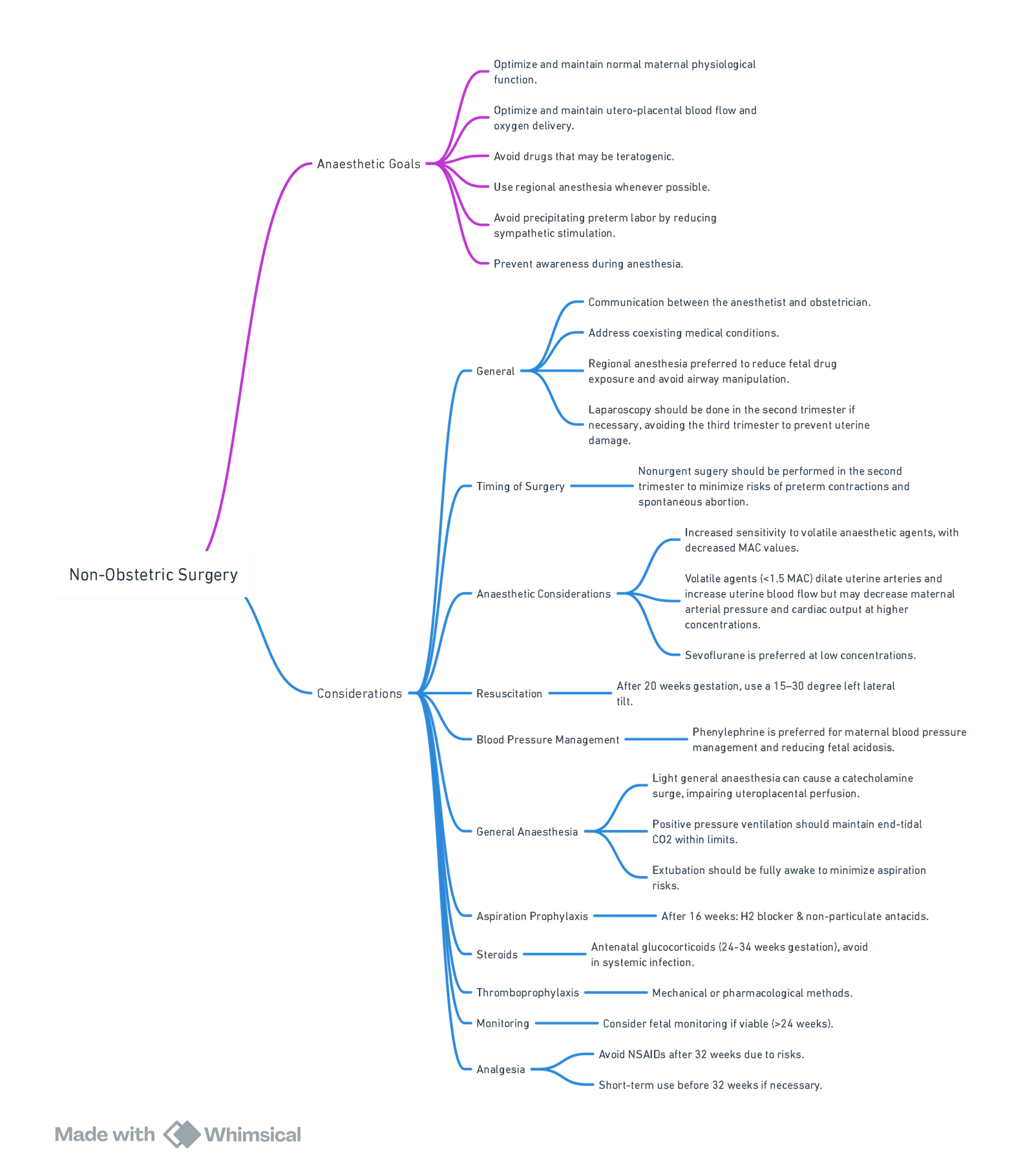

Conduct of Anaesthesia for Non-obstetric Surgery

Positioning

- Goal: Optimize surgical exposure while minimizing aortocaval compression by the gravid uterus.

- Beyond 18–20 weeks’ gestation, use a 15–30° left lateral tilt when supine to reduce aortocaval compression.

- In cases of hypotension, left lateral tilt (e.g., wedge under the right hip or tilting the table) or a left lateral decubitus position improves maternal hemodynamics.

- Fetal acid-base status remains preserved if maternal systolic blood pressure is maintained near baseline.

Monitoring

- Maternal Monitoring: Follow ASA standards for basic monitoring; advanced monitoring is determined by the procedure and patient comorbidities.

- Fetal Monitoring:

- Preand Postoperative: Fetal heart rate (FHR) and contractions should be documented for all pregnant patients.

- Intraoperative FHR Monitoring: Reserved for cases based on gestational age, surgery type, and resources. Most useful for identifying reversible causes of fetal distress (e.g., uterine hypoperfusion), although evidence does not show improved outcomes.

- All anaesthetic agents can reduce FHR variability, but worsened tracings may indicate maternal-fetal hemodynamic compromise.

Choice Of Anaesthetic Technique

-

Regional and Neuraxial Anaesthesia:

- Preferred to reduce fetal drug exposure, avoid maternal airway manipulation, and provide postoperative analgesia.

- Risks: Hypotension, which reduces uteroplacental perfusion. Mitigate with coloading fluids and prophylactic vasopressors (e.g., phenylephrine).

- Increased risk of local anaesthetic systemic toxicity due to pregnancy-related physiological changes (e.g., reduced protein binding).

-

General Anaesthesia:

- Commonly used but associated with rapid oxygen desaturation due to reduced functional residual capacity and increased oxygen consumption. Effective preoxygenation is critical.

- Rapid-sequence induction (RSI) is often performed after 15–18 weeks’ gestation, although the aspiration risk in pregnancy is low.

- Neuromuscular Blocking Agents: Suxamethonium may have prolonged action but is clinically insignificant. Sugammadex is not recommended routinely due to potential disruption of progesterone. Neostigmine with glycopyrrolate is commonly used for reversal.

-

Volatile and Intravenous Agents:

- Volatile agents are safe and may reduce uterine contractions.

- Propofol is the agent of choice for induction; use other agents and doses as per non-pregnant standards.

- Avoid ketamine due to increased uterine tone.

-

Sedation:

- Moderate and deep sedation are safe; avoid oversedation and hypoventilation to prevent fetal hypoxia and acidosis.

Ventilation Management

- Maintain increased minute ventilation to accommodate pregnancy-related respiratory alkalosis.

- Avoid profound hypoventilation (maternal hypercarbia → fetal acidosis) or hyperventilation (maternal hypocarbia → uteroplacental vasoconstriction).

- Plateau pressures up to 35 cm H₂O are well tolerated.

Temperature Management

- Maintain normothermia to avoid decreased FHR caused by reduced uteroplacental perfusion. Use warming devices (e.g., forced-air warmers, fluid warmers) and adjust room temperature as necessary.

Postoperative Care

-

Analgesia:

- Regional techniques, acetaminophen, and local anaesthetic wound infiltration are preferred.

- NSAIDs can be used in limited doses in the second and early third trimesters but are avoided otherwise due to risks of miscarriage or premature ductus arteriosus closure.

- Opioids are safe for acute pain but should be limited to short-term use.

-

Thromboprophylaxis:

- Pregnant patients are at a high risk of deep vein thrombosis and thromboembolism. Administer appropriate perioperative prophylaxis unless contraindicated.

Key Considerations

- Maternal Hemodynamics: Maintain systolic BP at 80–100% of baseline to ensure uteroplacental perfusion.

- Team Approach: A multidisciplinary team (anaesthesia, obstetrics, surgery, neonatology) is essential for optimal maternal and fetal outcomes.

- Urgency of Surgery: Do not delay urgent surgeries, as untreated maternal conditions pose greater risks to both the mother and fetus.

Summary of Conduct of Anaesthesia for Non-obstetric Surgery

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Different Surgeries

Cardiac Surgery

- Cardiovascular changes in pregnancy: 30–50% increase in blood volume and cardiac output, peaking at 24–28 weeks’ gestation.

- Risks with cardiopulmonary bypass:

- Non-pulsatile perfusion.

- Hypotension from inadequate perfusion pressure.

- Low pump flow.

- Embolic events to the uteroplacental circulation.

- Neurohormonal activation (renin, catecholamines).

Cardiopulmonary Bypass Considerations

- Maintain pump flow ≥ 30–50% above non-pregnant cardiac output.

- Perfusion pressure (MAP) ≥ 65 mm Hg.

- Haematocrit ≥ 28%.

- Normothermia (avoid < 32 °C to reduce fetal mortality).

- Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring when feasible.

- Tight control of acid–base, PaO₂ (≥ 100 mm Hg) and PaCO₂ (35–45 mm Hg).

Neurosurgery

- Haemodynamic targets: Avoid MAP < 70 mm Hg or systolic reduction > 25% to preserve uteroplacental flow.

- Ventilation: Avoid profound hyperventilation; maintain PaCO₂ 35–40 mm Hg to prevent uterine vasoconstriction.

- Mannitol: Limited to 0.25–0.5 g kg⁻¹; crosses placenta slowly and may reduce fetal lung fluid, but low doses appear safe.

Laparoscopy

- Injury mechanisms: Direct trauma, CO₂ absorption causing fetal acidosis, decreased cardiac output and uteroplacental perfusion from pneumoperitoneum.

- Timing: Preferably defer to second trimester.

Laparoscopic Technique

- Open (Hasson) entry technique.

- Insufflation pressure ≤ 12 mm Hg (1.6 kPa) or gasless methods.

- Monitor maternal end-tidal CO₂ (4–4.6 kPa).

- Slow position changes; limit Trendelenburg angles.

- Fetal heart rate and uterine tone monitoring when available.

Tubal Ligation

- Timing:

- Immediately post-cesarean section.

- Delayed 8–48 h postpartum for fasting.

- Elective at ≥ 6 weeks postpartum.

- Anaesthesia:

- Regional (spinal 8–12 mg bupivacaine or 60–75 mg lidocaine) preferred.

- Epidural catheter may remain for 48 h.

- GA with ETT for laparoscopic fulguration when required.

Fetal Monitoring

- Previable (< 24 weeks): Doppler FHR before and after surgery

- Viable (≥ 24 weeks): Electronic FHR and contraction monitoring pre‑ and postoperatively.

- Intraoperative monitoring: Only if:

- Fetus viable and gestation ≥ 24 weeks.

- Equipment and trained personnel available.

- Obstetric support ready for emergent cesarean delivery.

- Consent obtained for potential emergency delivery.

Links

- Maternal conditions

- Neurosurgery and pregnancy

- Laparoscopic surgery

- Obstetric emergencies

- Gynaecological Surgery

- Fetus and Placenta

- Breastfeeding

- Molar pregnancy

Past Exam Questions

Anaesthesia for Embolisation of a Spinal AVM in a Pregnant Patient

You are requested to provide anaesthesia for a 25-year-old G1P0 patient at 22 weeks gestation for embolisation of a symptomatic arteriovenous malformation (AVM) at T5-6.

a) Outline the main issues in anaesthetising this patient. (6)

b) The patient develops paraplegia after the procedure. She is then presented for urgent caesarean section at 35 weeks gestation for non-reassuring CTG in early labour.

i) What anaesthetic technique will you employ? (1)

ii) What precautions need to be taken in providing anaesthesia for this patient? (3)

References:

- Brakke, B. and Sviggum, H. P. (2023). Anaesthesia for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy. BJA Education, 23(3), 78-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2022.12.001

- Shin J. Anesthetic Management of the Pregnant Patient: Part 2. Anesth Prog. 2021 Jun 1;68(2):119-127. doi: 10.2344/anpr-68-02-12. PMID: 34185861; PMCID: PMC8258750.

- Reitman, E. and Flood, P. (2011). Anaesthetic considerations for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 107, i72-i78. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aer343

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Statement on Nonobstetric Surgery During Pregnancy. Arlington, VA: ASA; amended 17 October 2018. (asahq.org)

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 775: Nonobstetric Surgery During Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; April 2019. (acog.org)

- Howard MA, Grzybowski MM, Patterson JI, et al. Anaesthesia and non-obstetric surgery in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2024;58:103329. (obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- Smith MF, O’Neill MB, Sullivan EA. Pregnancy outcomes after non-obstetric surgery in the third trimester: A multicentre cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129(3):e31–e38. (journals.lww.com)

- Davidson AJ, Disma N, de Graaff JC, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(5):404–415. (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

Summaries:

Non-obstetric surgery

—

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “b44ad97c-22e4-4ff6-80a7-4993b4071582”