- Maternal Diabetes

- Epidemiology

- Maternal and Fetal Risks

- Key Management Principles

- Maternal Glycaemic Control During Labour

- Capillary Blood Glucose (CBG) Targets

- Practical Intrapartum Management

- Use of Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII)

- Anaesthetic Considerations

- Fluid Management (Especially with Pre-eclampsia)

- Postpartum Management

- Maternal Obesity

- Overview

- Definition and Classification

- Obesity Surgery Mortality Risk Stratification Score

- Pharmacokinetics in Morbid Obesity

- Drug Dosing in Obesity

- Maternal and Neonatal Complications

- Associated Conditions

- Cardiovascular System in Obesity

- Diabetes and Obesity

- Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

- General Anaesthesia: Key Points

- Neuraxial Anaesthesia

- Postoperative Management

- Preoperative Assessment

- Logistical Planning

- Labour Analgesia

- Caesarean Delivery Anaesthesia

- Postpartum Considerations

- Maternal Sepsis

- Definition

- Pathophysiology of Sepsis

- Risk Factors for Maternal Sepsis

- Causes of Sepsis in Pregnancy

- Clinical Features

- qSOFA Score (Quick SOFA)

- Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) in Pregnancy

- Initial Management (Hour-1 Bundle)

- Resuscitation Phase (First 6 Hours)

- Ongoing Management

- Pregnancy-Specific Considerations

- Antimicrobial Therapy

- Anaesthesia Considerations in Septic Pregnant Patients

- Delivery Decision

- Neonatal Outcomes

- Postoperative & Critical Care

- Peripartum Cardiomyopathy (PPCM)

- Definition

- Key Points

- Incidence

- Genetics

- Pathophysiology

- Clinical Presentation

- Diagnosis

- Role of B-type Natriuretic Peptides

- Prognostic Indicators

- Management

- Mechanical Circulatory Support (MCS)

- Arrhythmias

- Bromocriptine

- Lactation and Breastfeeding

- Delivery Planning

- Anaesthetic Considerations

- Postpartum Considerations

- Recovery and Outcomes

- Subsequent Pregnancy

- Myasthenia Gravis in Pregnancy

- EXIT Procedure

- Preterm Labour

- Chorioamnionitis

- Indications for Cesarean Section (C/S)

- Multiple Gestation

- Cervical Cerclage

- Links

- Past Exam Questions

{}

Maternal Diabetes

Epidemiology

- Globally, ~21.4 million women are affected by hyperglycaemia in pregnancy.

- In the UK, diabetes complicates 5% of pregnancies (~35,000/year).

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common form, followed by Type 1 (T1DM) and Type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

- GDM typically arises in the 2nd or 3rd trimester; if diagnosed earlier, suspect undiagnosed pre-existing diabetes.

Rising Prevalence (UK)

- T1DM in pregnancy increased from 1.56 to 4.09 per 1000 (1995–2012).

- T2DM increased from 2.34 to 10.62 per 1000 pregnancies.

- Driven by higher maternal age and BMI.

Maternal and Fetal Risks

- Maternal hyperglycaemia increases risk of:

- Macrosomia, birth trauma, preterm delivery, hyperbilirubinaemia.

- Congenital anomalies, stillbirth (5×), and neonatal death (3×).

- Caesarean delivery, worsening of retinopathy and nephropathy, pre-eclampsia, sepsis.

Key Management Principles

- Multidisciplinary approach essential: obstetrician, anaesthetist, diabetologist, midwife, diabetes nurse, dietitian.

- Goals during labour:

- Avoid maternal hypo-/hyperglycaemia.

- Reduce risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia.

- Safe glycaemic control (e.g. with VRII).

- Effective labour analgesia.

Maternal Glycaemic Control During Labour

Pathophysiology

- Maternal hyperglycaemia → fetal β-cell hyperplasia → ↑ fetal insulin → neonatal hypoglycaemia post-delivery.

- Also contributes to fetal overgrowth (macrosomia).

Evidence Summary

- Systematic review (1978–2016): mixed evidence; 12/23 studies found no link between maternal glycaemia and neonatal hypoglycaemia.

- NICE guidelines based on 10 observational studies (last in 2006); 2 studies demonstrated improved neonatal outcomes with maternal glucose <7 mmol/L.

Capillary Blood Glucose (CBG) Targets

Guidelines

- NICE (UK) and JBDS-IP: 4–7 mmol/L during labour and delivery.

- Canadian Diabetes Guidelines: also 4–7 mmol/L.

- Operative delivery (JBDS-IP): relaxed target of 5–8 mmol/L to reduce VRII use and complications.

Practical Intrapartum Management

Monitoring and Equipment

- Hourly CBG checks.

- Readily available:

- Glucometer, 20% glucose, infusion pumps.

- Midwives require:

- ≥2 h initial training on glucose management + annual updates.

VRII (Variable Rate Intravenous Insulin Infusion)

- Indicated if CBG not maintained between 4–7 mmol/L

- Basal insulin should be continued.

- Substrate fluid: 5% glucose in 0.9% saline + KCl (0.15%–0.30%).

- Initial rate: 50 mL/h, adjusted per fluid needs.

Common VRII Complications

- Programming or cannula errors.

- Omission of substrate fluid → DKA.

- Poor CBG monitoring → poor titration.

- Premature discontinuation → DKA (esp. T1DM).

Hyponatraemia risk: avoid pure 5% dextrose; oxytocin exacerbates fluid retention.

Use of Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion (CSII)

- T1DM patients may continue insulin pump during labour.

- Retrospective data: continuing CSII during labour improved glycaemic control vs switching to VRII.

- Safe if patient is competent; otherwise, switch to VRII if:

- CBG >7 mmol/L on ≥2 readings.

- Ketones >1.5 mmol/L.

- Individual care plan required for settings and monitoring.

- CSII can be continued perioperatively if feasible.

Anaesthetic Considerations

Neuraxial Anaesthesia

- Offers advantages due to high operative delivery risk.

- Incidence of hypotension ~10%.

- Crystalloid infusion typically commenced beforehand.

- Separate cannula recommended for VRII + substrate.

General Anaesthesia

- Increased risk of undetected hypoglycaemia due to loss of awareness.

- Frequent CBG monitoring is essential.

- Treat hypoglycaemia (CBG <4 mmol/L) with:

- 20% dextrose over 15 min.

- Pause VRII for 20 min.

- Recheck CBG in 10 min.

Fluid Management (Especially with Pre-eclampsia)

- Multiple infusions often required: insulin, substrate, oxytocin, magnesium, antihypertensives.

- Risk of pulmonary oedema with fluid overload.

- NICE recommends fluid restriction to 80 mL/h unless losses are ongoing.

- If on VRII but fluid restricted, consider running insulin without substrate fluid with caution.

Postpartum Management

General Principles

- Insulin requirements drop rapidly postpartum.

- Target CBG: 6–10 mmol/L.

- Avoid hypoglycaemia; encourage snacking after feeds, esp. if breastfeeding.

T1DM Or Insulin-Dependent T2DM

- Reduce VRII rate by 50% after delivery.

- Stop VRII 30–60 min after first meal.

- Resume s/c insulin per plan or give 50% of late-pregnancy dose if plan unavailable.

Pre-existing Diabetes on Oral Therapy

- Discontinue insulin after delivery if only used in pregnancy.

- Restart oral meds (e.g. metformin, glibenclamide) as per pre-pregnancy dose.

- CBG monitoring every 4 h until eating.

Gestational Diabetes

- High risk of future T2DM (up to 50% within 5 ears).

- Increased risk if GDM occurred early, required insulin, or with obesity.

- Ongoing monitoring and counselling essential.

Maternal Obesity

Society for Obesity and Bariatric Anaesthesia guidelines 2022

Overview

Obesity is a growing global health concern with increasing prevalence in women of childbearing age. Maternal obesity is associated with increased maternal morbidity and mortality, and obesity is consistently overrepresented in maternal death reports such as the UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths (CEMD).

Definition and Classification

- Obesity definition: Excessive or abnormal fat accumulation posing health risks.

WHO classification

| BMI (kg/m²) | Category |

|---|---|

| <18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5–24.9 | Normal |

| 25–29.9 | Overweight |

| 30–34.9 | Obese 1 |

| 35–39.9 | Obese 2 |

| 40–49.9 | Obese 3 (‘morbid obesity’) |

| 50–59.9 | Super obesity |

| ≥60 | Super-super obesity |

Obesity Surgery Mortality Risk Stratification Score

| Risk Factor | Score |

|---|---|

| BMI >50 kg/m² | 1 |

| Male | 1 |

| Age >45 years | 1 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Risk factors for PE: Previous VTE, hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension | 1 |

- Class A (0–1 points): 0.2–0.3% risk

- Class B (2–3 points): 1.1–1.5% risk

- Class C (4–5 points): 2.4–3.0% risk

Pharmacokinetics in Morbid Obesity

Physiological Changes

| System | Changes | Pharmacokinetic Result |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | ↑ Circulating blood volume, ↑ Cardiac output | ↑ Volume of distribution |

| Hepatic | Fatty liver, ↓ hepatic perfusion (e.g. CHF) | ↓ Hepatic clearance |

| Renal | ↑ Renal blood flow in early obesity, ↓ in chronic kidney disease | ↓ Renal clearance |

Body Weight Terminology

| Term | Description | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| TBW | Actual patient weight | Measured with weight scale |

| IBW | Ideal weight for height and sex | Broca: M: Height (cm) – 100; F: Height (cm) – 105. or M: IBW: 23 × height² (m); F IBW: 21 × height² (m) |

| LBW | Lean body mass (~85% TBW in non-obese) | M: LBW: 26 × height² (m); F LBW: 22 × height² (m) (Maximum: males 100 kg; females 70 kg) |

| ABW | Adjusted BW: compensates for ↑ fat and ↑ Vd | IBW + [0.4 × (TBW – IBW)] Excess=(TBW-IBW) |

Drug Dosing in Obesity

- TBW often overestimates dose; IBW may underestimate.

- Refer to SOBA guidelines below

- Lean Body Weight (LBW)

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Propofol (induction)

- Fentanyl and alfentanil

- Morphine

- Non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents

- Paracetamol

- Local anaesthetics

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Adjusted Body Weight (AdjBW = IBW + 40% excess)

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Propofol (infusion)

- Neostigmine (maximum 5 mg)

- Sugammadex

- Antibiotics

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Total Body Weight (TBW)

- Used for dosing:

- Suxamethonium

- Low-molecular-weight heparins

- Used for dosing:

- Lean Body Weight (LBW)

Maternal and Neonatal Complications

Maternal Complications

- Gestational diabetes

- Gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia

- Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA)

- Cardiovascular disease

- Thromboembolism

- Infection and sepsis

- Instrumental delivery

- Failed instrumental delivery

- Caesarean delivery

- Postpartum haemorrhage

- Longer hospital stay

Neonatal Complications

- Preterm delivery

- Miscarriage

- Small for gestational age

- Large for gestational age

- Macrosomia

- Stillbirth

- Shoulder dystocia

- Neural tube defects

- Neonatal death

- Neonatal ICU admission

Associated Conditions

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA) in Pregnancy

- Prevalence:

- General pregnancy: ~15%

- BMI >35 kg/m²: ~43.3%

- Associations: ↑ risk of gestational diabetes (aOR 1.86) and pre-eclampsia (aOR 2.34)

- Diagnosis:

- Gold standard: Overnight PSG (limited in pregnancy)

- Alternative: Watch-PAT 200 (validated with high accuracy)

- Management: Refer for sleep studies if indicated

Cardiovascular System in Obesity

- ↑ Cardiac workload, CO, BP, and risk of arrhythmias (e.g., AF)

- Risk of heart failure ↑ 7% per 1 kg/m² BMI increase

- ↑ QT interval with BMI

- Obesity is a risk factor for sudden cardiac death due to SA node dysfunction and myocardial infiltration

Diabetes and Obesity

- Obesity strongly associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

- BMI ≥40 increases diabetes risk 7-fold

- Poorly controlled diabetes → ↑ risk of:

- Wound infection

- Acute renal failure

- Postoperative leaks

- Associated with fetal macrosomia, ↑ CD rate, and NICU admission

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

- Risk ↑ 4× in pregnancy; 20× in postpartum

- Highest risk: 2 days before to 1 day after delivery

- RCOG Recommendations:

- BMI >30 + ≥2 other risk factors: Consider LMWH antepartum

- BMI >40 at delivery: LMWH for at least 7 days postpartum

General Anaesthesia: Key Points

Airway Management

- Desaturation significantly shorter (2–3 mins vs 8–10 mins)

- ↑ risk of difficult mask ventilation vs intubation

Preoxygenation Strategies

- Use ramped or reverse Trendelenburg position

- Apply PEEP during induction

- Improved oxygenation (PaO₂ 242 vs 183 mmHg; Saxena et al.)

- Apnoeic oxygenation:

- HFNO ↑ safe apnoea time by 76s (Wong et al.)

- No significant difference between 10 L/min and 120 L/min flows

- Face mask with PEEP may outperform HFNO in oxygenation

Intubation

- Video laryngoscopy preferred

- Ramped position improves laryngeal view (Collins et al.)

- Modified ramed positioning enhances intubation (Hasanin et al.)

Neuraxial Anaesthesia

Challenges

- ↑ Risk of epidural failure (RR 1.5) and dural puncture (4% vs 1%)

- Landmark identification and positioning more difficult

- Use sitting, flexed position

- Ultrasound guidance:

- ↓ attempts (median 1 vs 5)

- ↓ procedure time

- ↑ success

Choice of Technique

- Preferred: CSE

- Combines rapid onset and extended duration

- Reduced risk of GA

- Single-shot spinal:

- May be insufficient if procedure is prolonged

- Conflicting evidence on need to reduce dose

- Epidural:

- Risk of sacral sparing; avoid de novo if possible

Postoperative Management

Pain Management

- Opioids ↑ risk of sedation, respiratory depression

- Use multimodal opioid-sparing analgesia

- Consider:

- Neuraxial morphine

- US-guided TAP block (technical challenges in obesity)

- Double catheter technique for thoracic epidural analgesia

Monitoring and Mobilisation

- Continuous respiratory monitoring (esp. if OSA)

- Use compression devices and encourage early mobilisation

- Consider extended postoperative VTE prophylaxis

Preoperative Assessment

Recommendations

- All parturients with BMI >40 kg/m² should undergo anaesthetic review in the third trimester.

- Performed by a senior anaesthetist.

- Focus on comorbidities: OSA, hypertension, cardiac disease, reflux, and diabetes.

- Detailed examination: airway, respiratory and cardiovascular systems.

- Early neuraxial planning and patient education recommended.

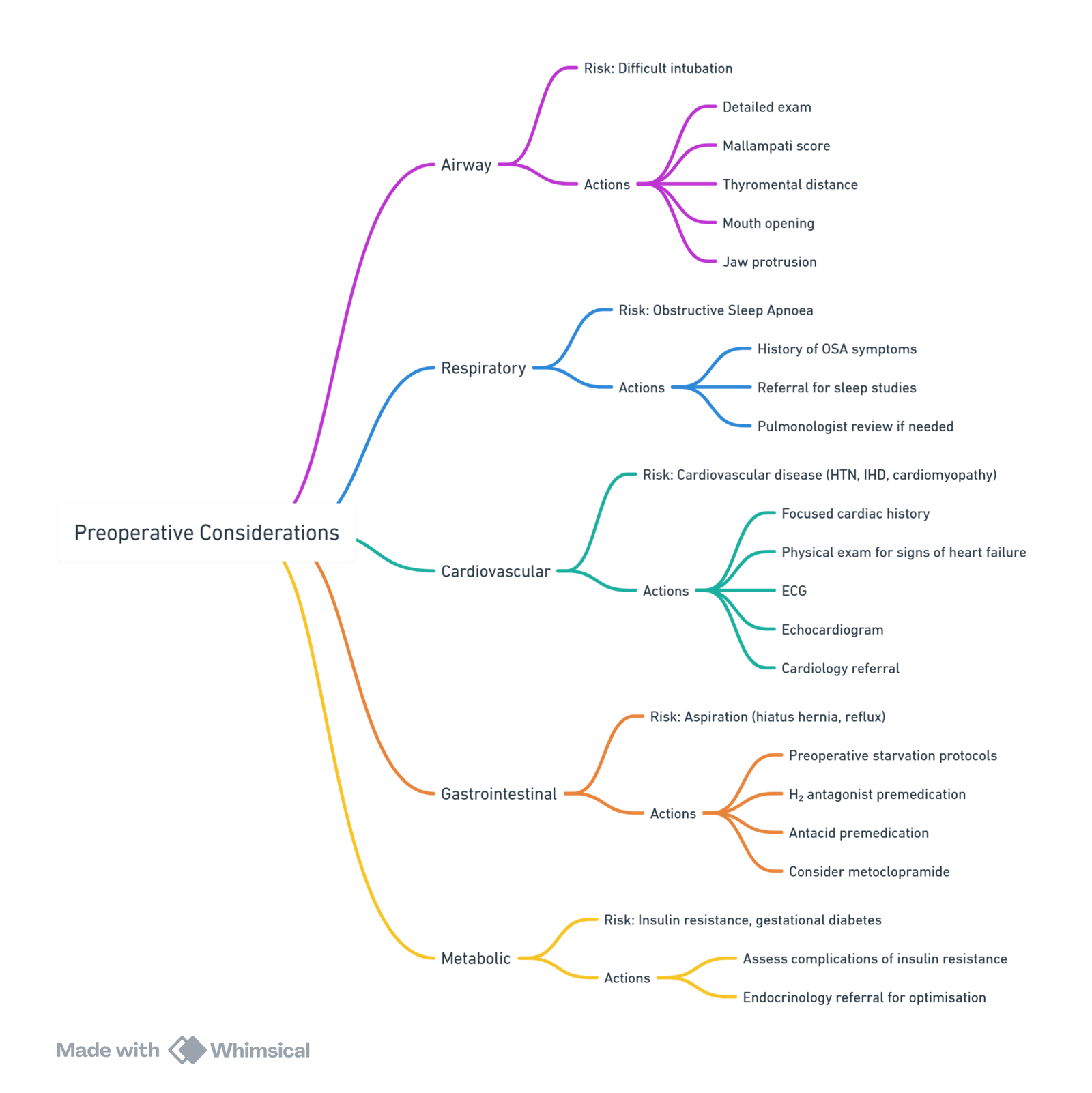

Preoperative Considerations

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Logistical Planning

- Delivery in consultant-led obstetric unit for BMI >35 kg/m².

- Adequate equipment: long epidural/spinal needles, US machines, wide NIBP cuffs, patient handling aids.

- US-guided peripheral access; consider arterial and central access if needed.

- Plan early mobilisation to theatre for potential CD.

Labour Analgesia

Neuraxial Analgesia (Preferred)

- Epidural, CSE, or DPE techniques preferred.

- Early placement advised due to technical difficulty.

- Use ultrasound to identify landmarks and reduce attempts.

- Long needles may be required; start with standard length.

- Secure catheter after repositioning to avoid displacement.

- Continuous reassessment required.

CSE and DPE Techniques

- CSE: Reliable analgesia; CSF confirmation reduces failure rate.

- DPE: Improved sacral spread; CSF return improves confidence of midline placement.

Maintenance Strategies

- Continuous infusion

- Patient-controlled epidural analgesia

- Programmed intermittent bolus

(No comparative data specific to obesity)

Non-Neuraxial Options

- Nitrous oxide and oxygen (limited efficacy)

- Opioids used with caution due to OSA risk

- Consider acupuncture or TENS (limited evidence)

Caesarean Delivery Anaesthesia

Patient Positioning

- Ramped with left uterine displacement improves intubation view and ventilation.

- Protect pressure points.

Surgical Exposure

- Panniculus retraction: Cephalad (watch for hypotension, fetal compromise), or vertical suspension.

- Consider supraumbilical midline incisions in morbid obesity.

Infection Prophylaxis

- Consider cefazolin 3g if >120 kg, but data inconclusive.

- Re-dosing and postoperative cephalexin/metronidazole may help but not yet standard.

Neuraxial Anaesthesia for CD

- Single-shot spinal: Use cautiously in BMI >50 kg/m².

- CSE: Dense reliable block; adjustable dose; avoids GA.

- Epidural: Use if labour catheter in place; avoid de novo if possible due to patchy block.

- Double catheter: Lumbar for surgery, thoracic for pain and high incision.

General Anaesthesia

- Use ramped position and head-up for preoxygenation.

- CPAP or pressure support ventilation to enhance preoxygenation.

- Apnoeic oxygenaton via nasal prongs or HFNO (THRIVE) may be beneficial.

- Use video laryngoscopy; have difficult airway equipment ready.

- Dosing

- Lean Body Weight (LBW)

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Propofol (induction)

- Fentanyl and alfentanil

- Morphine

- Non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents

- Paracetamol

- Local anaesthetics

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Adjusted Body Weight (AdjBW = IBW + 40% excess)

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Propofol (infusion)

- Neostigmine (maximum 5 mg)

- Sugammadex

- Antibiotics

- Used mostly for dosing:

- Total Body Weight (TBW)

- Used for dosing:

- Suxamethonium

- Low-molecular-weight heparins

- Used for dosing:

- Lean Body Weight (LBW)

- Extubation in awake, semi-upright position; initiate CPAP in OSA.

Postpartum Considerations

Analgesia

- Multimodal approach; neuraxial morphine recommended even in obesity.

- Monitor respiratory status (especially with OSA).

- If neuraxial opioid contraindicated:

- Use i.v. PCA cautiously

- Consider TAP/QL block or surgical wound infiltration

- Thoracic epidural (if double catheter placed) for analgesia

Thromboprophylaxis

- Early mobilisation

- Mechanical: Compression devices and stockings

- Pharmacological: According to local VTE guidelines

Level of Postpartum Care

- Ward: Healthy with uncomplicated delivery

- High-dependency or ICU: Comorbidities, complications, or monitoring needs

Maternal Sepsis

Definition

WHO (2017)

- Maternal sepsis: Life-threatening organ dysfunction resulting from infection during pregnancy, childbirth, post-abortion, or postpartum.

Sepsis-3 Definition (2016)

- Sepsis: Life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.

- Organ dysfunction = Increase in SOFA score by ≥2 points.

Septic Shock

- Subset of sepsis with:

- Hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain MAP ≥65 mmHg

- Serum lactate >2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL)

- In the absence of hypovolemia

Pathophysiology of Sepsis

- Dysregulated host response → systemic inflammation

- Capillary leak → intravascular hypovolemia

- Decreased systemic vascular resistance; increased cardiac output

- Septic cardiomyopathy: biventricular systolic/diastolic dysfunction

- Complications: Ischemia, DIC, pulmonary oedema

Risk Factors for Maternal Sepsis

- Obesity, diabetes, anaemia, immunosuppression

- Vaginal discharge, pelvic infections, GBS history

- Amniocentesis, cerclage, prolonged ROM, Caesarean

- Retained products, GAS contact

Causes of Sepsis in Pregnancy

Obstetric

- Retained products (placenta, abortion)

- Chorioamnionitis, endometritis, pelvic abscess

Non-Obstetric

- Appendicitis, pneumonia (bacterial/viral), pancreatitis

Clinical Features

Symptoms

- Fever/temperature instability, tachycardia, tachypnea

- Diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, hypotension

- Pain at infection site, altered mental state

Lab Findings

- Leukocytosis/leukopenia, positive cultures

- ↑ lactate, metabolic acidosis, thrombocytopenia

- ↑ creatinine/LFTs, hypoxemia, hyperglycemia (non-DM)

qSOFA Score (Quick SOFA)

- Score ≥2 → High risk of poor outcome

| Parameter | Criteria | Points |

|---|---|---|

| RR | ≥22/min | 1 |

| SBP | ≤100 mmHg | 1 |

| GCS | Altered mental state | 1 |

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) in Pregnancy

- Temp >38°C or <36°C (2x in 4h)

- HR >100 bpm (2x in 4h)

- RR >20/min (2x in 4h)

- WCC >17 or <4×10⁹/L, or >10% bands

Initial Management (Hour-1 Bundle)

Within 1 Hour of Suspected Sepsis:

- Obtain cultures + measure serum lactate

- Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Initiate fluid therapy:

- 30 mL/kg crystalloid (adjust for pregnancy)

- Target MAP >65 mmHg

Resuscitation Phase (First 6 Hours)

- Blood cultures before antibiotics

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics within 1 hour

- Measure serum lactate

- If hypotensive or lactate >4 mmol/L:

- 30 mL/kg crystalloids

- Vasopressors (norepinephrine) if MAP <65 mmHg

- Persistent shock:

- Target CVP ≥8 mmHg

- Target ScvO₂ ≥70%

- Position pregnant woman in left lateral tilt to prevent aortocaval compression

Ongoing Management

Vasopressors

- First-line: Norepinephrine

- Add: Vasopressin/Epinephrine if needed

- Dopamine: Only in low risk of tachyarrhythmias

- Dobutamine: If hypoperfusion despite vasopressors

Corticosteroids

- IV Hydrocortisone 200 mg/day

- Only if refractory shock

- Also used for fetal lung maturation (if 23–24 weeks gestation)

Glucose Control

- Maintain glucose <10 mmol

Source Control

- Early imaging/surgical intervention as needed

Pregnancy-Specific Considerations

Fetal Monitoring

- Start electronic fetal monitoring at ≥24 weeks

DVT Prophylaxis

- LMWH or UFH

- Use compression devices

Nutrition

- Initiate early enteral feeding

Antimicrobial Therapy

Common Choices

- Piperacillin–tazobactam or meropenem (broadest)

- Gentamicin: 3–5 mg/kg once (renal safe single dose)

- Clindamycin, teicoplanin or linezolid (MRSA)

- Avoid co-amoxiclav (↑ risk NEC in neonates)

WHO Guidance

- Chorioamnionitis: Ampicillin + Gentamicin

- Endometritis: Clindamycin + Gentamicin

Anaesthesia Considerations in Septic Pregnant Patients

General Anaesthesia

- Preferred for C-section

- Agents: Etomidate/Ketamine + Rocuronium

- Invasive monitoring (A-line, CVP, CO)

Regional Anaesthesia

- Generally contraindicated:

- Hypotension risk

- Coagulopathy or infection risk

Delivery Decision

- Multidisciplinary discussion required

- Indications for delivery:

- Intrauterine infection, DIC, MOF, ARDS

- Fetal demise or viable gestational age

- Avoid delivery during maternal instability unless source control required

Neonatal Outcomes

- ↑ risk of neonatal sepsis, hypoxia, respiratory distress, neurological impairment

- High neonatal mortality with maternal sepsis

Postoperative & Critical Care

- Transfer to ICU if:

- Hemodynamic instability needing vasopressors

- Mechanical ventilation

- Organ failure (renal, CNS, etc.)

- Post-op analgesia: Paracetamol + opioids

- Avoid NSAIDs

Peripartum Cardiomyopathy (PPCM)

Definition

PPCM is an idiopathic cardiomyopathy causing heart failure due to left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction, occurring towards the end of pregnancy or within months postpartum, in the absence of any other identifiable cause of heart failure.

- LV ejection fraction (LVEF) is usually <45%

- PPCM is a diagnosis of exclusion

- Clinical presentation varies widely and may be difficult to distinguish from normal pregnancy

Key Points

- PPCM is a form of heart failure that may be life-threatening

- Symptoms often overlap with normal pregnancy, potentially delaying diagnosis

- BNP/NT-proBNP measurement is recommended in symptomatic pregnant patients (e.g. orthopnoea or PND)

- Vaginal delivery with neuraxial analgesia is preferred where possible

- History of PPCM increases risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies

Incidence

- Global incidence: ~1 in 1000 live births

- Increasing incidence in high-income countries likely due to:

- Advanced maternal age

- Assisted reproductive technologies

- Obesity, diabetes, hypertension

- Hypertensive pregnancy disorders

- High gravidity/parity

- Family history of cardiomyopathy

Genetics

- Increased prevalence of genetic mutations in women of African descent

- Mutations found up to 20 times more often in PPCM than in healthy controls

- Often shared with dilated cardiomyopathy

- These mutations may be unmasked by cardiovascular stress of pregnancy

Pathophysiology

- Multifactorial, involving:

- Genetic predisposition

- Oxidative stress

- Antiangiogenic signalling

Oxidative Stress & Prolactin Hypothesis

- Placental oxidative stress → activation of proteases → cleavage of prolactin

- 16-kDa prolactin fragment:

- Antiangiogenic

- Promotes endothelial apoptosis and dysfunction

- Reduces cardioprotective mechanisms

- Enhanced prolactin secretion in pregnancy and breastfeeding may explain peripartum onset

Shared Mechanisms with Pre-eclampsia

- Elevated soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFLT-1) seen in both conditions

- Inhibits VEGF, promoting endothelial dysfunction

Clinical Presentation

- Highly variable, from subacute to fulminant heart failure or cardiogenic shock

- Around two-thirds present postpartum

- LVEF <36% in most at diagnosis

- Severe symptoms common: NYHA Class III-IV

Diagnosis

History & Clinical Assessment

- Key symptoms: dyspnoea, orthopnoea, PND, fatigue

- Risk factor evaluation: e.g. previous chemotherapy, substance use, HIV

ECG

- Non-specific changes:

- ST depression

- T-wave inversion

- QTc prolongation (associated with LVEF <35%)

Chest X-ray

- May show cardiomegaly, pulmonary oedema

- Not sensitive; a normal CXR does not exclude PPCM

Echocardiography

- First-line and gold-standard

- Findings:

- LVEF commonly ~30%

- May show LV dilatation and functional mitral regurgitation

- RV dysfunction at baseline = poor prognostic marker

- Intracardiac thrombi possible

Cardiac MRI

- Useful to exclude other causes (e.g. myocarditis, LV non-compaction)

- Avoid gadolinium in pregnancy

Differentiating PPCM from Pre-eclampsia

- Pre-eclampsia typically causes diastolic dysfunction

- PPCM causes systolic dysfunction

- Use of BP, proteinuria and echocardiography helps differentiate

Other Differentials

- Pulmonary embolism

- Amniotic fluid embolism

- Myocardial infarction

- Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (especially post-stress or catecholamines)

Role of B-type Natriuretic Peptides

- BNP and NT-proBNP rise in heart failure

- Normally low in pregnancy; elevated levels support diagnosis

- May help rule out cardiac disease when normal

- Higher levels (e.g. NT-proBNP >900 pg/mL) associated with poor LV recovery

Prognostic Indicators

Factors Associated with Poor Prognosis in PPCM

- African ethnicity

- Previous history of PPCM

- LVEF <30% at diagnosis

- LV dilatation (EDD >60 mm)

- Diagnosis delayed >1 week from symptom onset

- Right ventricular dysfunction

- Prolonged QT interval

- LV thrombus

- NT-proBNP >900 pg/mL

- Obesity

Management

Overview

- Management mirrors that of congestive heart failure (CHF) with supportive and pharmacological therapy.

- Requires individualised care considering:

- Gestation and fetal viability

- Maternal haemodynamics

- Risk to mother with continuation of pregnancy

- Breastfeeding implications

Multidisciplinary Team (Pregnancy Heart Team)

Essential members

- Cardiologist

- Obstetrician

- Obstetric anaesthetist

- Maternal fetal medicine specialist

- Critical care midwifery/nursing

Additional (as required): - Intensivist, cardiothoracic anaesthetist, neonatologist, pharmacist

Pharmacological Management

Safe Medications in Pregnancy and Lactation

| Drug Class | Use in Pregnancy | Use in Lactation | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers (e.g. metoprolol) | Yes | Yes | IUGR, fetal bradycardia, hypoglycaemia |

| Loop diuretics | Yes | Yes (caution) | Monitor placental perfusion and milk production |

| Hydralazine + Nitrates | Yes | Yes | Use as afterload reduction |

| Digoxin | Yes | Yes | Standard heart failure treatment |

| ACE inhibitors / ARBs | No (pregnancy) | Yes (postpartum) | Fetotoxic in utero. Enalapril and captopril safe in lactation |

| Spironolactone | No | Yes | Avoid in pregnancy due to antiandrogenic effects |

| Sacubitril-Valsartan | No | Unknown | Avoid in pregnancy and lactation |

| Ivabradine | Avoid | Avoid | Insufficient data |

| LMWH | Yes | Yes | Preferred anticoagulant in pregnancy |

| Warfarin | Avoid (antenatal) | Yes (postpartum) | Teratogenicity in early pregnancy |

Key Priorities in Acute Decompensation

-

Optimise preload

- Cautious fluid challenge if hypovolaemic

- IV loop diuretics if congested

- Vasodilators (e.g. GTN) if SBP >110 mmHg

-

Oxygenation support

- Face mask or non-invasive ventilation

- Invasive ventilation if deteriorating

-

Haemodynamic support

- Inotropes/vasopressors depending on patient response

-

Urgent delivery

- If unstable despite optimal medical therapy

-

Bromocriptine

- Consider post-delivery to inhibit prolactin

- Requires anticoagulation

-

Anticoagulation

- For LV thrombus, embolism, or AF

- LMWH preferred before delivery

Mechanical Circulatory Support (MCS)

- Consider early in refractory cardiogenic shock

- Modalities:

- Impella, intra-aortic balloon pump (adequate oxygenation)

- Venoarterial ECMO (cardiogenic shock)

- Venovenous ECMO (isolated respiratory failure)

- Complications: bleeding, infection, thrombosis, fetal mortality

- May transition to LVAD if unweanable after 7–10 days

Arrhythmias

- High arrhythmia risk if LVEF <35%

- Cardioversion/defibrillation safe during pregnancy

- ICD: if persistent LV dysfunction after 6 months

- Pacemakers rarely indicated

Bromocriptine

- Dopamine agonist—inhibits prolactin

- Shown to improve LV recovery in small RCTs

- ESC 2018 Guidelines recommend consideration in severe PPC

- Thromboprophylaxis mandatory during use

Lactation and Breastfeeding

- Individualised decision

- No strong evidence linking breastfeeding to worse outcomes

- May reduce metabolic load in severe cases

- Most HF medications safe during lactation

Delivery Planning

mWHO Classification

- Class III: LVEF 30–45% or previous PPCM with recovered function

- Class IV: LVEF <30% or persistent LV dysfunction post-PPCM

- Class III/IV → deliver in expert cardiac obstetric centre

Timing and Mode of Delivery

- Vaginal delivery preferred if stable

- Early delivery only if maternal/fetal compromise

- Plan delivery to manage anticoagulation and cardiac support

Anaesthetic Considerations

General Principles

- Multidisciplinary team and experienced personnel

- Continuous ECG, pulse oximetry, arterial line monitoring

- Early neuraxial analgesia

- Low threshold for vasopressors/inotropes

- Avoid fluid overload

- Use concentrated oxytocin infusions instead of boluses

Labour Analgesia

- Epidural or CSE techniques preferred

- Titrate bupivacaine 0.0625–0.125% incrementally

- Avoid adrenaline test dose

- Maintain with local anaesthetic + opioid (e.g. bupivacaine + fentanyl)

Caesarean Delivery

- Neuraxial anaesthesia preferred (epidural or low-dose CSE)

- Consider slow, graded doses to avoid hypotension

- Use vasopressors (phenylephrine) or inopressors (norepinephrine, ephedrine) as needed

- GA only if necessary (e.g. anticoagulation or deterioration)

- Continuous BP monitoring and obtund intubation response

Postpartum Considerations

- Risk of acute decompensation due to autotransfusion

- Oxytocin: dilute, slow infusion

- Avoid carboprost/ergometrine unless necessary

- Tranexamic acid: safe unless thrombotic complications

Recovery and Outcomes

- Full recovery (LVEF >50–55%) in 21–63% at 6 months

- Early deaths: arrhythmia, acute HF, embolism

- Long-term therapy if LV dysfunction persists

- Continue heart failure therapy for ≥1 year after recovery

- Taper slowly based on function

Subsequent Pregnancy

- Increased risk of recurrence, even with normalised function

- Pregnancy discouraged if LVEF <50%

- Requires close specialist monitoring

Myasthenia Gravis in Pregnancy

Introduction

- Myasthenia Gravis (MG): autoimmune neuromuscular disorder, peak onset in women aged 20–30.

- Pregnancy can exacerbate pre-existing MG, particularly via respiratory compromise.

- Multidisciplinary planning is essential for safe peripartum care

Incidence and Prevalence of MG

- Incidence: 50–140 per million

- Prevalence: 1 in 10,000 to 50,000

Pathophysiology

- Autoantibodies target nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChR) at the postsynaptic neuromuscular junction.

- Leads to reduced ACh binding, impaired transmission, and fatigable weakness of voluntary skeletal muscles.

- Bulbar involvement (pharyngeal/laryngeal weakness): dysphagia, dysarthria.

Diagnosis

- Anticholinesterase test: edrophonium improves strength.

- EMG: decremental response with repetitive nerve stimulation.

- AChR antibodies: positive in 85% (generalised MG), 50–60% (ocular MG).

- Screen for coexisting autoimmune diseases (thyroid disease, SLE, RA).

Treatment

Pharmacological Management

- First-line: pyridostigmine (anticholinesterase).

- Immunosuppression: corticosteroids (safe), azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate (avoid in pregnancy).

- Adjust pyridostigmine dose in pregnancy due to ↑ volume of distribution and renal clearance.

- Consider parenteral route if absorption is impaired (e.g., hyperemesis).

Myasthenic vs. Cholinergic Crisis

| Feature | Myasthenic Crisis | Cholinergic Crisis |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Under-treatment | Over-treatment (excess anticholinesterase) |

| Pupils | Normal or dilated | Constricted (miosis) |

| Secretions | Normal | Increased salivation and lacrimation |

| Muscle weakness | Generalised | Generalised + fasciculations |

| Bowel/bladder | Normal | Diarrhoea, abdominal cramps |

| Treatment | IVIG or plasmapheresis | Withhold anticholinesterase, atropine |

Other Considerations

- 15% of MG cases associated with thymoma.

- Thymectomy may reduce symptom severity and hospitalisation.

Physiological Changes in Pregnancy Relevant to MG

- ↓ Lower oesophageal sphincter tone → ↑ risk of aspiration, particularly in bulbar involvement.

- Intercostal muscle weakness + pregnancy-related ↓ FRC and RV → may precipitate respiratory failure (rare).

- Uterus (smooth muscle) not affected by MG → 1st stage of labour unaffected.

- 2nd stage may require assisted delivery to avoid fatigue.

Neonatal Myasthenia Gravis

- 10–20% risk due to transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies.

- Presents with hypotonia, poor feeding, respiratory distress.

- Usually resolves within 8 weeks; may require ventilation and anticholinesterase.

- Avoid breastfeeding if neonatal MG is diagnosed.

- Pyridostigmine is safe in breastfeeding; avoid azathioprine and mycophenolate during lactation.

Drugs That May Exacerbate MG

- Calcium channel blockers: May impair neuromuscular transmission via L-type calcium channel blockade; verapamil reduces potassium outflow; felodipine/nifedipine potentially worsen MG with long-term use.

- Anti-arrhythmics (e.g. procainamide, propafenone): Decrease ACh release and act as sodium channel blockers; can exacerbate MG.

- H₂ receptor antagonists: Animal studies show ACh inhibition; caution advised despite lack of human data.

- Aminoglycosides: Affect both preand postsynaptic transmission; gentamicin inhibits ACh release (reversible by neostigmine).

- Macrolides: Linked to MG exacerbation; mechanism unclear.

- Antiepileptics: Phenytoin reduces postsynaptic response; carbamazepine and gabapentin may unmask MG.

- Magnesium sulphate: Contraindicated due to neuromuscular blocking effects.

- Neuromuscular blockers: Suxamethonium contraindicated; risk of hyperkalaemia from depolarisation of extrajunctional ACh receptors.

Anaesthetic Considerations

- Respiratory muscle weakness

- Bulbar dysfunction (aspiration risk)

- Autonomic dysfunction (hypotension, bradycardia)

Recommendations for Management

Preoperative Assessment

- History: exacerbations, respiratory support, bulbar signs

- Physical exam: neurological and respiratory function, supine tolerance

- Bloods: FBC, U&Es, renal function, thyroid function, autoimmune screen

- Investigations: ECG, pulmonary function tests

- Multidisciplinary team involvement: anaesthetics, obstetrics, neurology, ICU

Labour Management

- MG does not mandate caesarean section.

- Avoid systemic opioids and PCA if respiratory compromise exists.

- Epidural analgesia preferred:

- Cautious titration to T10

- Use low-dose LA + opioid (e.g., 0.0625% bupivacaine + fentanyl 2 µg/mL)

- One-to-one monitoring recommended

- Continue anticholinesterase and steroid therapy

- Assisted delivery may be necessary during second stage to prevent fatigue

Anaesthesia for Caesarean Delivery

Premedication

- Metoclopramide + H2 antagonist (avoid drugs contraindicated in MG)

- Avoid benzodiazepines and systemic opioids

Intraoperative Considerations

- Avoid hypovolaemia and ensure left lateral tilt

- Invasive BP monitoring if autonomic dysfunction

Neuraxial Techniques

Epidural

- Titrate local anaesthetic doses

- Benefits: stable CV profile, lower risk of high block

- Suitable for mild respiratory/autonomic involvement

Spinal

- Low total dose, fast onset

- Risk: cardiovascular instability, unmodifiable block height

Combined Spinal-Epidural (CSE)

- Reliable, rapid onset with backup epidural dosing

- Favoured in many obstetric settings

General Anaesthesia

- Reserved for:

- Severe respiratory impairment

- Contraindication to neuraxial technique

- Avoid suxamethonium

- ↑ Sensitivity to non-depolarising muscle relaxants → use low doses, monitor with TOF

- Consider:

- Sugammadex for rocuronium

- Neostigmine for rocuronium/atracurium (use with caution due to cholinergic crisis risk)

- Use short-acting IV opioids, minimal volatile agents

Oxytocin

- Administer cautiously: may worsen hypotension

- Use slow IV doses or infusion

Postoperative Care

-

HDU/ICU monitoring recommended

-

Monitor:

- Respiratory function (spirometry)

- Secretions and airway clearance

- CV status and fluid balance

-

Support:

- Chest physiotherapy

- Noninvasive/invasive ventilation if required

-

Resume oral anticholinesterase therapy as early as possible

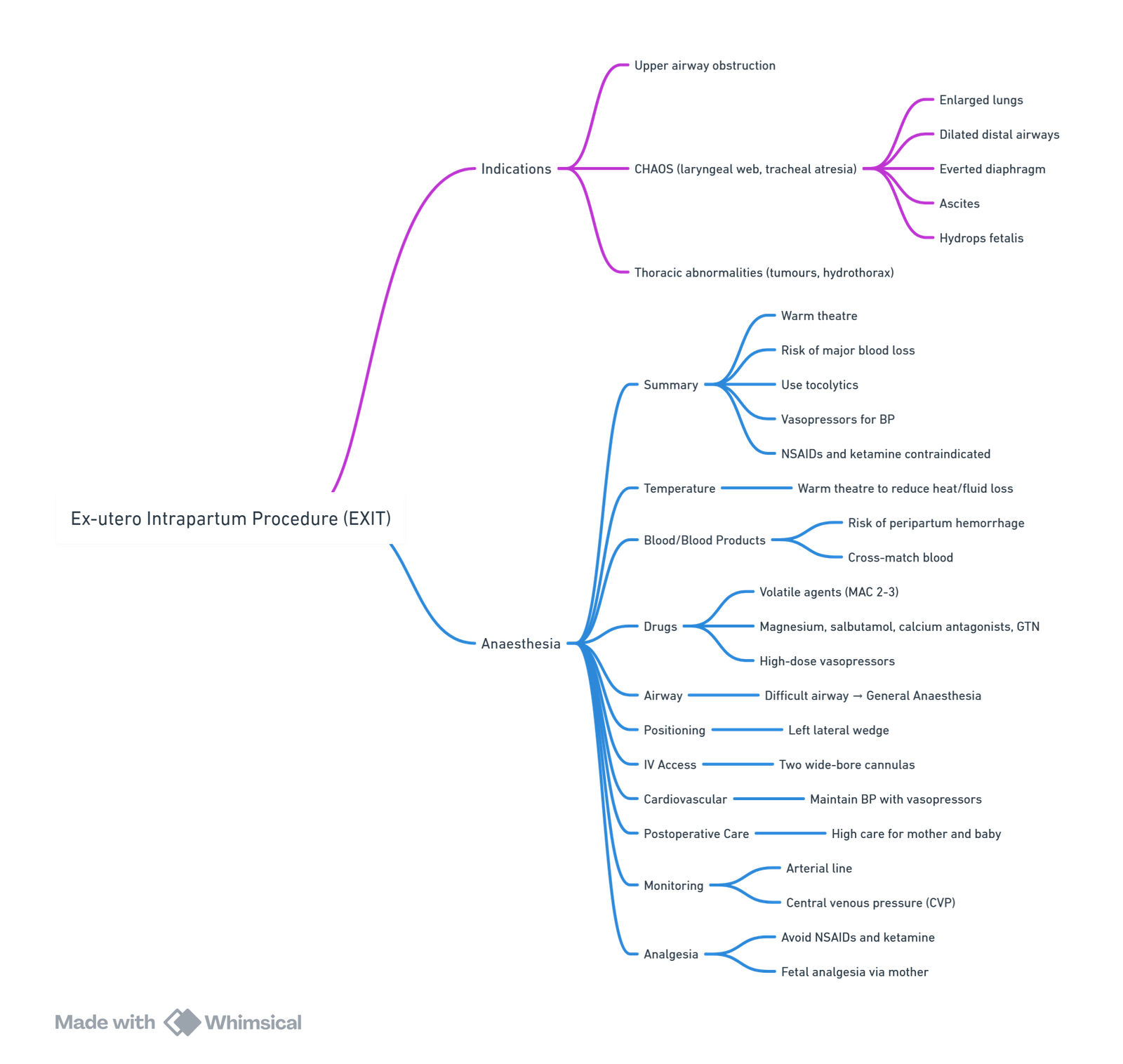

EXIT Procedure

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Preterm Labour

Preterm Labour

- Occurs between 20 to 37 weeks.

Tocolytics

- β2 agonist (terbutaline):

- Maternal side effects: tachycardia, arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, mild hypotension, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia, and rarely, pulmonary edema.

- Residual effects may complicate general anaesthesia. Use ketamine, ephedrine, and isoflurane cautiously.

- May interfere with uterine contraction following delivery.

- MgSO4:

- Potentiates muscle relaxants.

- May predispose to hypotension secondary to vasodilation.

- Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine) and prostaglandin synthetase inhibitors.

Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis

- Signs: fever (>38°C), maternal and fetal tachycardia, uterine tenderness, and foul-smelling or purulent amniotic fluid. WCC >15.

- In the absence of overt signs of septicemia, thrombocytopenia, or coagulopathy, regional anaesthesia is not contraindicated.

Indications for Cesarean Section (C/S)

Maternal

- Prior cesarean delivery

- Maternal request

- Pelvic deformity or cephalopelvic disproportion

- Previous perineal trauma

- Prior pelvic or anal/rectal reconstructive surgery

- Herpes simplex or HIV infection

- Cardiac or pulmonary disease

- Cerebral aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation

- Pathology requiring concurrent intraabdominal surgery

- Perimortem cesarean

Fetal

- Nonreassuring fetal status (e.g., abnormal umbilical cord Doppler study, abnormal fetal heart tracing)

- Umbilical cord prolapse

- Failed operative vaginal delivery

- Malpresentation

- Macrosomia

- Congenital anomaly

- Thrombocytopenia

- Prior neonatal birth trauma

Uterine/Anatomical

- Abnormal placentation (e.g., placenta previa, placenta accreta)

- Placental abruption

- Prior classical hysterotomy

- Prior full-thickness myomectomy

- History of uterine incision dehiscence

- Invasive cervical cancer

- Prior trachelectomy

- Genital tract obstructive mass

- Permanent cerclage

Multiple Gestation

Considerations for Multiple Gestation (Twins)

- Considerations of pregnancy, full stomach, 3 patients.

- Increased Maternal Complications:

- Increased aorto-caval compression.

- Increased desaturation.

- Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM).

- Preterm labor.

- Prolonged labor.

- Pre-eclampsia/eclampsia.

- Placental abruption.

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

- Operative delivery.

- Uterine atony.

- Antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH).

- Increased Fetal Complications:

- Preterm delivery.

- Congenital anomalies.

- Polyhydramnios.

- Cord entanglement.

- Umbilical cord prolapse.

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

- Twin-to-twin transfusion.

- Malpresentation.

- Increased mortality.

Anaesthetic Management

- Trial of Labour & Vaginal Delivery (if both twins have vertex presentation):

- Ensure very good epidural and 2 large bore IVs.

- Ensure OR and personnel ready for stat GA at any time, especially for delivery of twin B.

- Have nitroglycerine available for uterine relaxation if needed for internal version and breech extraction of twin B.

- Cesarean Section (more common scenario):

- Ensure 2 large bore IVs and active cross match.

- Epidural, spinal, and GA are all safe for cesarean section.

- Aortocaval compression and rapid desaturation are exaggerated.

- Have nitroglycerine ready for uterine relaxation.

- Be prepared for postpartum hemorrhage, need for resuscitation, and uterotonics.

- Neonatal resuscitation team must be present.

Cervical Cerclage

Introduction

- Patients with cervical incompetence present for modified Shirodkar or McDonald suture, both done transvaginally at 14-18 weeks.

- These procedures increase fetus survival from 20% to 89%.

- Patients present with painless, recurrent second-trimester miscarriages.

- For patients with bulging membranes, there is concern about rupturing the membranes during the procedure.

Considerations

- Pregnancy considerations: difficult intubation, aspiration, decreased time to desaturation, aortocaval compression, two patients.

- Risk of membrane rupture and degree of cervical dilation may dictate mode of anaesthesia.

- Potential need for uterine relaxation and avoidance of coughing, straining, position changes that provoke bulging and rupture of membranes.

Management

- Depends on degree of cervical dilation with options of spinal, epidural, or GA for transvaginal cerclage.

- If no cervical dilation:

- Typically spinal (or epidural) anaesthesia requiring a T10 to S4 block.

- If cervical dilation present:

- Goals: produce adequate analgesia, prevent increase in intrauterine/intraabdominal pressure.

- Type of anaesthesia depends on presence of bulging membranes and need for uterine relaxation:

- Spinal:

- Risk of sitting position and lumbar spine flexion leading to bulging of membranes, rupture, and fetal death.

- Consider placing spinal/epidural in lateral position.

- Dose: 7.5 mg isobaric bupivacaine with fentanyl 15 mcg; alternative is 40 mg lidocaine.

- Epidural:

- Midlumbar, 2% lidocaine with 5 mcg/mL epinephrine (10-15 mL total volume) with 100 mcg fentanyl for T8 block.

- General:

- Indicated if bulging membranes to facilitate uterine relaxation with volatile anaesthetics.

- Risks: coughing, bucking, vomiting leading to rupture of membranes; avoid GA in second trimester due to risks to fetus and parturient.

- Spinal:

Removal of Cervical Cerclage

- Removed at 37-38 weeks; earlier if rupture of membranes or labor begins.

- McDonald cerclage suture removal requires no anaesthesia.

- Shirodkar suture removal requires anaesthesia due to suture epithelialization; options are spinal or epidural.

- Highly epithelialized sutures may require cesarean section.

- If epidural catheter placed, consider leaving it as labor may ensue within a few hours.

Links

- Anaesthesia emergencies

- Obstetric haemorrhage

- Obstetric emergencies

- Breastfeeding

- Non obstetric surgery

- Gynaecological Surgery

- Maternal collapse and CPR

- Fetus and Placenta

- Obstetric physiology

- Maternal sepsis

Past Exam Questions

Anaesthetic Considerations in Morbidly Obese Pregnant Patients

a) What are the major anaesthetic problems that the morbidly obese parturient presents? (6)

b) What are the specific problems of providing neuraxial anaesthesia for caesarean delivery in morbidly obese patients? (3)

c) For spinal anaesthesia, how will you adjust the dose? (1)

Challenges of Anaesthetising the Morbidly Obese Patient for Caesarean Section

List the challenges of anaesthetizing the morbidly obese patient for caesarean section. (10)

References:

- Patel, S. and Habib, A. S. (2021). Anaesthesia for the parturient with obesity. BJA Education, 21(5), 180-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2020.12.007

- Chen C, Xu X, Yan Y. Estimated global overweight and obesity burden in pregnant women based on panel data model. PLoS One 2018;13(8):e0202183.

- Onubi OJ, et al. Maternal obesity in Africa: a systematic review and metaanalysis. J Publ Health 2016;38(3):e218e31.

- Csa I. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa. Maryland, USA: Ethiopia and Calverton; 2016.

- Kassie AM, Abate BB, Kassaw MW. Education and prevalence of overweight and obesity among reproductive age group women in Ethiopia: analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Publ Health 2020;20(1):1e11.

- Carron M, et al. Perioperative care of the obese patient. J. Br. Surg. 2020;107(2):e39e55.

- Pani N, Mishra SB, Rath SK. Diabetic parturient – Anaesthetic implications. Indian J Anaesth. 2010 Sep;54(5):387-93. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.71028. PMID: 21189875; PMCID: PMC2991647.

- Yap, Y. F., Modi, A., & Lucas, N. (2020). The peripartum management of diabetes. BJA Education, 20(1), 5-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2019.09.008

- Chapman, K., Njue, F., & Rucklidge, M. W. M. (2023). Anaesthesia and peripartum cardiomyopathy. BJA Education, 23(12), 464-472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2023.08.002

- Almeida C, Coutinho E, Moreira D, Santos E, Aguiar J. Myasthenia gravis and pregnancy: anaesthetic management–a series of cases. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010 Nov;27(11):985-90. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32833e263f. PMID: 20733499.

- Banner, H., Niles, K. M., Ryu, M., Sermer, M., Bril, V., & Murphy, K. E. (2022). Myasthenia gravis in pregnancy: systematic review and case series. Obstetric Medicine, 15(2), 108-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495×211041899

- The Calgary Guide to Understanding Disease. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/

- FRCA Mind Maps. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.frcamindmaps.org/

- Anesthesia Considerations. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://www.anesthesiaconsiderations.com/

- ICU One Pager. (2024). Retrieved June 5, 2024, from https://onepagericu.com/

- Recommendations for thromboprophylaxis in obstetrics and gynaecology E Schapkaitz. S Afr J Obstet Gynaecol 2018;24(1):xx-xx. DOI:10.7196/SAJOG.2018.v24i1.1312

Summaries:

C-section

Obesity in pregnancy

—

Copyright

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “1ce7cec1-33ed-4f33-bc84-c08d8aae0722”