- Sedation

- Sedation Levels and Monitoring

- Sedation Continuum

- Consent (and Shared Decision-Making)

- Goals of Procedural Sedation

- Contra-Indications

- Patient Preparation

- Equipment & Environment—SOAPME

- Monitoring Standards

- Documentation

- Staffing Requirements

- Pharmacology—Key Agents

- Sedation Outside the Operating Theatre

- South African Context–Safe Sedation (SASA 2022 Consolidated)

- ICU Sedation & Analgesia

- Emerging Sedation Agents

- Links

- Past Exam Questions

{}

Sedation

Sedation Levels and Monitoring

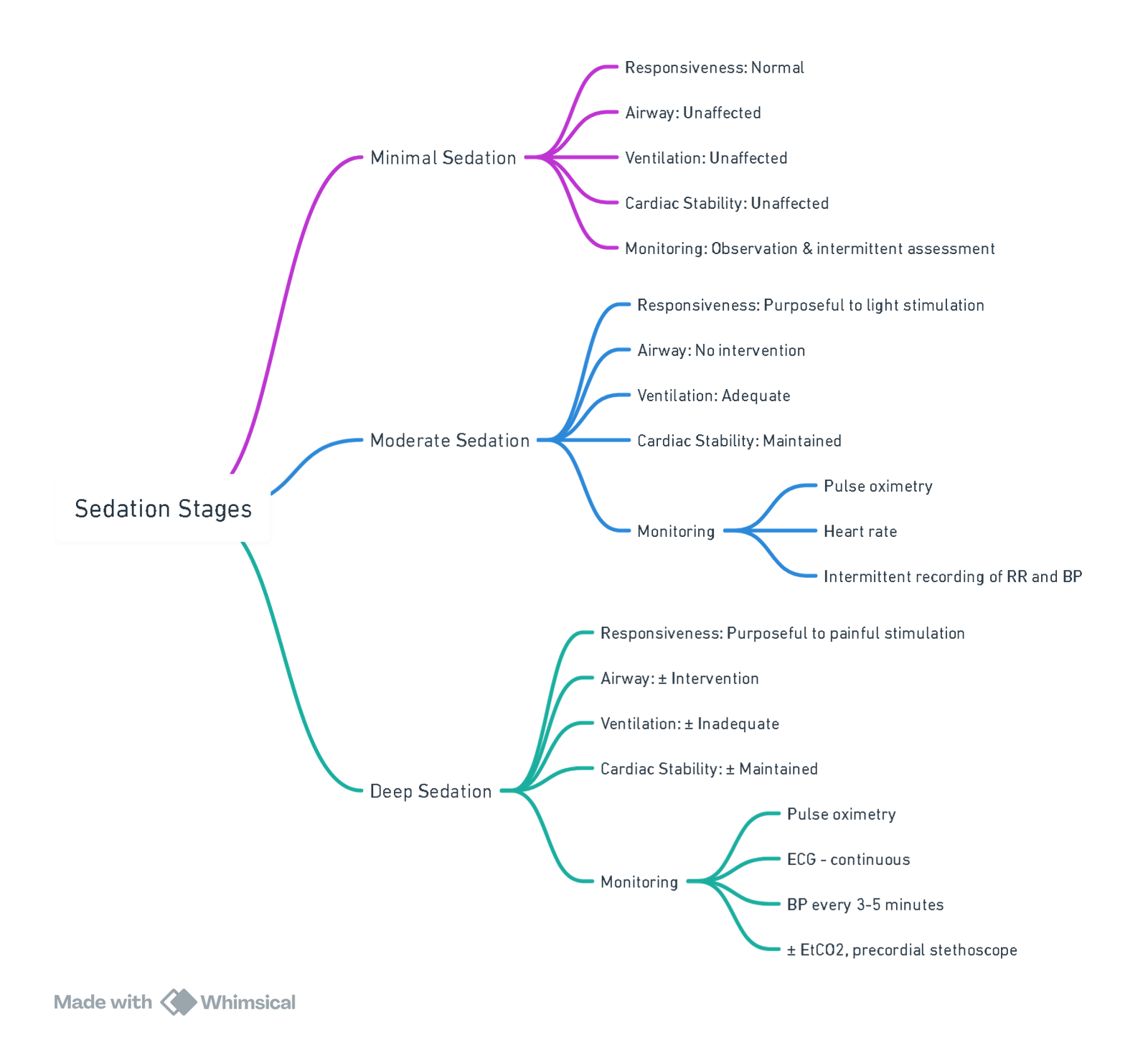

View or edit this diagram in Whimsical.

Sedation Continuum

| Level | Responsiveness | Airway | Spontaneous ventilation | CVS function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (Anxiolysis) | Normal response to verbal stimulation | Unaffected | Unaffected | Unaffected |

| Moderate (“Conscious”) | Purposeful response to verbal/tactile stimulation | No intervention required | Adequate | Usually maintained |

| Deep | Purposeful response only after repeated/painful stimulation | Intervention may be required | May be inadequate | Usually maintained |

| General anaesthesia | Unarousable | Intervention often required | Frequently inadequate | May be impaired |

Sedation exists on a dynamic continuum; clinicians must be able to “rescue” patients who progress to a deeper plane than intended. In the UK, deep sedation is regulated as part of general anaesthesia.

Consent (and Shared Decision-Making)

- Written, procedure-specific consent must include:

- Description of the planned procedure and sedation technique

- Benefits and material risks (e.g. hypoxaemia 0.6–1.0 %, unplanned airway intervention 0.1–0.3 %)

- Alternatives (local anaesthesia alone, regional block, general anaesthesia)

- Possibility of sedation failure and conversion to GA

- Post-procedural recovery expectations and discharge criteria

Goals of Procedural Sedation

- Respect patient autonomy and comfort

- Provide anxiolysis, amnesia and analgesia appropriate to the procedure

- Maintain protective airway reflexes and cardiorespiratory stability

- Facilitate timely completion of the intervention with rapid recovery and discharge readiness

Contra-Indications

Absolute

- Inability to maintain/secure airway (e.g. severe OSA with daytime desaturation, craniofacial abnormality)

- Raised ICP with risk of herniation

- Glasgow Coma Scale < 14 or evolving neurological deficit

- Acute decompensated respiratory or cardiac failure

- Active lower-respiratory tract infection with hypoxaemia

- Known allergy to proposed sedative/adjuncts

- Refusal or lack of valid consent

Relative

- Prematurity (< 60 weeks post-conceptual age)

- ASA ≥ III (unoptimised) or haemodynamic instability

- Severe renal or hepatic impairment affecting drug metabolism

- Full stomach / inadequate fasting when deep sedation is planned

- Concomitant CNS-depressant therapy (opioids, anticonvulsants, macrolides)

- Behavioural disorders that preclude cooperation despite minimal sedation

Patient Preparation

- Fasting (2020 international consensus)

- Clear fluids: ≥ 2 h

- Breast milk: ≥ 4 h

- Light meal / non-human milk: ≥ 6 h

- Minimal or moderate sedation in low-risk patients may proceed regardless of fasting state if benefits outweigh aspiration risk, provided airway manoeuvres and GA capability are immediately available.

Equipment & Environment—SOAPME

| Letter | Requirement |

|---|---|

| S–Suction | Two working suction sources; wide-bore Yankauer and paediatric catheters. |

| O–Oxygen | Primary pipeline supply and full E-cylinder (≥ 2000 psi) onsite, with low-pressure alarm. |

| A–Airway | Age-appropriate BVM, oral/nasopharyngeal airways, videolaryngoscope, second-generation supraglottic airway, ETTs with stylets/bougie; cricothyrotomy kit if help is distant. |

| P–Pharmacy | Immediate-use drugs (vasopressors, anticholinergics, sedatives, neuromuscular blockers, reversal agents) stored in tamper-evident tackle box; emergency dantrolene if a volatile agent is available. |

| M–Monitors | Continuous ECG, NIBP, SpO₂, capnography (mandatory for all moderate/deep sedation and GA), inspired O₂, temperature; audible alarms on. |

| E–Everything else | OR-equivalent anaesthesia machine with waste-gas scavenging, defibrillator/ pacing pads, forced-air warmer, radiation shielding (where relevant), compliant electrical outlets, reliable two-way communication with main theatre, adequate lighting. |

Monitoring Standards

| Sedation depth | Clinical | Electronic minimum | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (≤ 30 min) | Continuous observation of colour, respiratory pattern | Intermittent HR, SpO₂, NIBP | Suitable for single-agent oral/IN midazolam or N₂O ≤ 50 % |

| Moderate | As above + responsiveness scoring | SpO₂, ECG, NIBP every 5 min, capnography† | †Capnography reduces hypoxaemia by ~50 % and is recommended whenever an intravenous agent is used |

| Deep / GA | Full anaesthetic monitoring | SpO₂, ECG, NIBP, continuous EtCO₂, temperature, neuromuscular function if paralytics used | Treat as GA outside theatre; airway equipment and trained anaesthetist mandatory |

Documentation

- Pre-procedure: consent form, anaesthetic assessment, fasting status, airway classification, checklist

- Intra-procedure: time-stamped record of drugs and doses, vital signs q 5 min, complications and rescue measures

- Post-procedure: recovery scoring (e.g. Aldrete), discharge instructions including transport and 24-h emergency contact

Staffing Requirements

| Technique | Sedationist role | Assistant | Operator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal (single oral/IN agent, ≤ 30 min) | Operator-sedationist | Competent observer records vitals | Same person |

| Moderate | Dedicated sedationist (not involved in procedure) | Assistant to help rescue | Separate proceduralist |

| Deep / GA | Anaesthetist with GA rescue skills | Trained airway assistant | Operator |

The SASA 2021–26 paediatric guideline mandates that deep sedation be delivered only by doctors credentialed in anaesthesia.

Pharmacology—Key Agents

| Drug | Adult bolus | Onset / duration | Advantages | Main cautions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | 1 mg every 1–2 min IV (total ≈ 0.05–0.1 mg kg⁻¹) | 2 min / 20–40 min | Reliable anxiolysis, amnesia | Paradoxical agitation 15 %; resp depression when combined with opioids |

| Propofol | 20–30 mg every 30 s (titrate) | 30 s / 5–10 min | Rapid recovery; anti-emetic | Sudden airway obstruction/apnoea; hypotension; propofol-infusion syndrome with > 48 h high-dose infusions |

| Ketamine | 0.5–1 mg kg⁻¹ IV or 4 mg kg⁻¹ IM | 1 min / 10–20 min | Preserves airway tone, potent analgesia | Hypersalivation, emergence reactions (↓ with midazolam 0.02 mg kg⁻¹) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 0.5–1 µg kg⁻¹ over 10 min then 0.2–0.7 µg kg⁻¹ h⁻¹ | 5 min / context-sensitive | Rousable, minimal resp depression | Bradycardia, hypotension, rebound HTN during loading |

| Remimazolam | 5 mg IV over 1 min; repeat 2.5 mg q 2 min (max 0.2 mg kg⁻¹) | 1 min / 10–20 min | Ultra-short context-sensitive half-time; reversible with flumazenil | Limited post-marketing data; avoid with severe hepatic failure |

Flumazenil 0.2 mg (adult) or 20–30 µg kg⁻¹ (child) IV antagonises benzodiazepines; Naloxone 40 µg IV incrementally reverses opioids.

Sedation Outside the Operating Theatre

- Only ASA I–II patients without difficult-airway predictors

- “Basic” techniques (single oral/IN agent, N₂O ≤ 50 %) allowed for operator-sedationist model

- Any combination therapy, N₂O > 50 %, TIVA/TCI, or propofol/ketamine automatically upgrades to advanced sedation requiring full monitoring and a dedicated anaesthetist

- Discharge criteria: awake, vital signs ± 20 % baseline, able to ambulate (or age-appropriate norm), minimal nausea/pain, responsible adult escort

South African Context–Safe Sedation (SASA 2022 Consolidated)

All procedural sedation must be planned, titrated and monitored as an anaesthetic; the ability to “rescue” a patient who drifts to a deeper plane is mandatory.

| Domain | Key requirements (SASA 2022) |

|---|---|

| Patient selection | Elective out-of-theatre sedation restricted to ASA I–II adults/children with no anticipated difficult airway. Stable ASA III patients only if a credentialled anaesthetist is present. |

| Pre-assessment | Focused airway exam (Mallampati, neck mobility, mouth opening), fasting status, cardiorespiratory comorbidity, medication review (esp. CNS depressants). |

| Dosing philosophy | Titrate in small, incremental aliquots allowing ≥ 1 min between doses; avoid fixed boluses. Document total dose and effect. |

| Environment & equipment | SOAPME checks; full anaesthetic monitoring for any IV, multi-drug or deep sedation (SpO₂, ECG, NIBP q 5 min, continuous EtCO₂). |

| Personnel | Operator-sedationist permitted only for single-agent minimal sedation ≤ 30 min. All other techniques require a dedicated sedationist with airway skills. |

| Recovery & discharge | Aldrete ≥ 9, stable vitals for 30 min, able to ambulate (or age-appropriate norm), responsible adult escort, written post-sedation instructions. |

ICU Sedation & Analgesia

2025 SCCM Focused PADIS Update–Headline Changes

- Target light sedation (RASS −2 to 0) in all mechanically ventilated adults unless specific indications for deep sedation exist.

- Analgesia-first strategy: fentanyl or remifentanil infusions before initiating sedatives.

- Preferred sedatives

- Propofol or dexmedetomidine over benzodiazepines in all patient groups, including post-cardiac surgery.

- Remimazolam may be considered when haemodynamic stability is critical, but evidence remains limited.

- Sedation optimisation: daily SAT + SBT (paired), nurse-driven protocols, and objective sedation scoring every 2–4 h

- Adjunct monitoring: processed EEG (BIS 40–60) when deep sedation or neuromuscular blockade is required.

Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS)

| Score | Response | Clinical action |

|---|---|---|

| +4 to +1 | Combative → Restless | Treat pain/anxiety, consider haloperidol/dexmedetomidine, provide reassurance |

| 0 | Alert & calm | Maintain |

| −1 to −2 | Drowsy → Light sedation | Acceptable target for most ICU patients |

| −3 | Moderate sedation | Review indication; attempt SAT |

| −4/−5 | Deep sedation / Unrousable | Ensure indication (e.g. ARDS proning); initiate EEG or BIS |

Proceed to delirium screening (CAM-ICU) if RASS ≥ −2.

ICU Liberation ABCDEF Bundle–2024 Evidence

- A Assess, prevent & manage pain

- B Both SAT & SBT daily

- C Choice of analgesia/sedation (avoid benzodiazepines, prefer propofol/dex)

- D Delirium assessment (CAM-ICU q 12 h); non-pharmacological first-line

- E Early mobilisation within 48 h of stability

- F Family engagement at bedside or virtually

Multicentre data in > 6 000 ventilated adults show full bundle compliance reduces 28-day mortality by 25 % and delirium days by 50 %.

Emerging Sedation Agents

| Drug | ICU / Procedural role | Key advantages | Key cautions | Recent evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remimazolam | Procedural sedation; explored for ICU infusion | Ultra-short context-sensitive half-time, haemodynamic stability, reversible with flumazenil | Slightly longer awakening vs propofol; respiratory depression similar to midazolam | 2025 meta-analysis (11 RCTs, n = 5 642)–↓ hypoxaemia, ↓ hypotension vs propofol |

| Fospropofol disodium | Endoscopy & elderly day-case sedation | Water-soluble (no lipid emulsion), minimal injection pain | Delayed onset (4-8 min); paraesthesia; formaldehyde metabolite | 2024 RCT in elderly endoscopy–non-inferior efficacy, ↓ hypotension vs propofol |

| Methoxyflurane (Penthrox®) | Self-administered inhalational analgesia for short procedures | Rapid onset, minimal respiratory depression, short recovery | Nephrotoxic metabolites–avoid eGFR < 60 mL min⁻¹ 1.73 m⁻²; occupational exposure; limited paediatric data | 2023 systematic review–effective adjunct or alternative to IV midazolam/opioid sedation, faster discharge times |

Practical Pearls

- Remimazolam dosing (adult): 6 mg IV over 1 min; 2.5 mg repeats q 2 min (max ≈ 0.2 mg kg⁻¹).

- Fospropofol dosing: 6.5 mg kg⁻¹ IV over 60 s; supplemental 1.6 mg kg⁻¹ q 4 min.

- Methoxyflurane: 3 mL inhaler provides ≈ 25 min analgesia; patient controls concentration via finger on dilutor port. Provide supplemental O₂ if SpO₂ < 94 %.

Links

- Day case surgery

- Paediatric sedation

- Total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA)

- Paediatric Total Intravenous Anaesthesia (TIVA)

- Delirium and sedation

- Premedication

- Post op complications

- Recovery

- Practice guideline

- Practical Protocols and recipes

Past Exam Questions

Sedation for Biventricular Pacing-Defibrillator Insertion

List your main concerns when assessing a patient’s suitability for sedation for this procedure. (10)

Safe Practice for Operator-Sedationist

A plastic surgical colleague wants to sedate patients in his procedure room for minor cosmetic procedures. He asks for advice, as he plans to sedate patients himself without an anaesthetist present.

What information (based on SASA procedural sedation guidelines) would you provide as a guideline for safe practice? (10)

References:

- Khorsand, S., Karamchandani, K., & Joshi, G. P. (2022). Sedation-analgesia techniques for nonoperating room anesthesia: an update. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 35(4), 450-456. https://doi.org/10.1097/aco.0000000000001123

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia. Practice Guidelines for Moderate Procedural Sedation and Analgesia 2018. Anesthesiology 2018;128:437-479. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29334501 PubMed

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Safe Sedation Practice for Healthcare Procedures–Update 2021. London: AoMRC, 2021. https://www.aomrc.org.uk AOMRC

- South African Society of Anaesthesiologists. Paediatric Guidelines for Procedural Sedation and Analgesia 2021–2026. SAJAA 2021;27(Suppl 2):S1-83. painsa.org.za

- An international multidisciplinary consensus statement on fasting before procedural sedation in adults and children. Anaesthesia 2020;75:374-385. Anaesthetists Publications

- McCracken GC, Smith AF. Breaking the fast for procedural sedation: changing risk or risking change? Anaesthesia 2020;75:1010-1013. PubMed

- Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Best Practice Guideline: Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department. RCEM 2022. ABEM

- Jhuang BJ et al. Efficacy and safety of remimazolam for procedural sedation: meta-analysis of RCTs. Front Med 2021;8:641866. PubMed

- South African Society of Anaesthesiologists. Guidelines for the Safe Use of Procedural Sedation and Analgesia (2nd ed.). SAJAA 2016. sajaa.co.za

- South African Society of Anaesthesiologists. Anaesthesia Practice Guidelines–Consolidated 2022. Johannesburg: SASA; 2022. sasaweb.com

- Lewis K, Balas MC, Stollings JL, et al. A focused update to the PADIS guideline. Crit Care Med 2025;53:e711-e727. Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM)

- Kerson AG, Deem S, Cooke CR. Validation of the Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale across ICU populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;208:1125-1134. ATS Journals

- Girard TD, Pun BT, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Implementing the ABCDEF bundle improves survival and brain function. Crit Care Explor 2024;6:e0945. Lippincott Journals

- Zhong J, Liu B, Wang Y, et al. Remimazolam vs propofol for procedural sedation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2025;140:256-268. PubMed

- Zhang H, Chen Q, Li R, et al. Remimazolam for high-risk GI endoscopy: randomised trial. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2023;33:100689. PubMed

- Liu X, Deng T, Huang G, et al. Fospropofol vs propofol for elderly bidirectional endoscopy: RCT. Front Pharmacol 2024;15:1378081. [Frontiers](https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2024.1378081/full?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Reeve R, Rades T, Wood MJ. Inhaled methoxyflurane for procedural analgesia: systematic review. Pain Pract 2023;23:456-470. PMC

- de Klerk R, Jonas K. Methoxyflurane vs fentanyl–midazolam for office hysteroscopy: protocol. ClinTrials.gov NCT06899724 (accessed 25 Jul 2025). ClinicalTrials.gov

- Developing capnography standards for procedural sedation. Front Med 2022;9:867536. Frontiers

- BJA Education. Developments in procedural sedation for adults. BJA Educ 2022;22:190-196. BJAED

- Kodali BS. Capnography outside the operating room. Anesthesiology 2013;118:192-201 (still current for technical standards)

- SASA. (2020). SASA Guidelines for the safe use of procedural sedation and analgesia for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in adults: 2020–2025. The South African Society of Anaesthesiologists. Retrieved from SASA website.

- Sneyd, J. R. (2022). Developments in procedural sedation for adults. BJA Education, 22(7), 258-264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2022.02.006

Summaries:

Day-case

Copyright**

© 2025 Francois Uys. All Rights Reserved.

id: “54906ac6-1c79-44d9-9b5f-06f744e55fcf”